England show impressive positional dynamics in Russia draw

England kicked off their Euro campaign at the stunning Stade Velodrome in Marseilles on Saturday night. Their first opponents were Russia, under the stewardship of CSKA Moscow manager Leonid Slutsky following the well-publicised soap opera that was the departure of Fabio Capello. Vasili Berezutski’s last minute header snatched a draw for the Russians, though England fans have much to be optimistic about over the coming weeks.

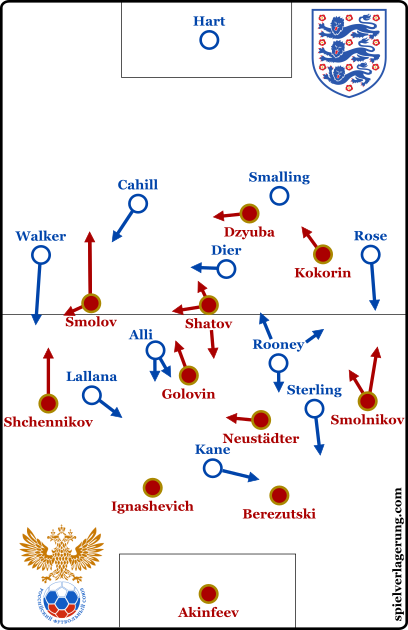

Lineups

Roy Hodgson was fairly conservative, if not predictable, in his selection. Playing Wayne Rooney in midfield alongside Eric Dier and Dele Alli, the team were spearheaded by Harry Kane, flanked by Adam Lallana and Raheem Sterling. Kyle Walker made his major international tournament debut at right back, while Danny Rose completed the Tottenham delegation at left back.

Roy Hodgson was fairly conservative, if not predictable, in his selection. Playing Wayne Rooney in midfield alongside Eric Dier and Dele Alli, the team were spearheaded by Harry Kane, flanked by Adam Lallana and Raheem Sterling. Kyle Walker made his major international tournament debut at right back, while Danny Rose completed the Tottenham delegation at left back.

Leonid Slutsky, on the other hand, was forced to stray away from the tried and tested. Late injuries to Alan Dzagoev and Igor Denisov meant a start for Aleksandr Golovin in the centre of midfield – the latest revelation in Russian football, who turned 20 less than a couple of weeks prior. Roman Neustädter made his competitive debut for Russia having received confirmation of his naturalisation application from President Vladimir Putin. Russia enter yet another tournament with a defensive unit primarily composed of players from CSKA Moscow, as Sergei Ignashevich earned his 118th cap alongside Vasili Berezutski, Georgi Shchennikov and goalkeeper Igor Akinfeev.

England’s Early Dominance through Positional Dynamics

England started their Euro campaign brightly as Roy Hodgson’s side displayed attractive, attacking football belying their manager’s reputation for favouring rigid, counter-attacking approaches. One of the key contributing factors in this perceived change in style was their use of positional dynamics. Dynamic positioning allows a team’s formation to morph into one of many potential forms at various points in the attacking process.

The benefits of dynamic positioning over static are both widespread and plentiful. These are primarily based around the effects that a player moving from one position to another may have on man-oriented defenders, but also affect more subtle elements, such as body positioning and perception.

England utilised this through rotation in the midfield, switching from their 4-3-3 to a 4-2-3-1. Rooney would often drop deep alongside Dier in possession, playing with the Russian midfield in front of him. This allowed him to play relatively unpressured, since Russia’s front players were somewhat ineffective in their pressing. Despite coming under increased criticism in recent years, Rooney undoubtedly possesses a great range of passing, and is capable of using this to create structural advantages. In one scenario, he was able to switch the ball from an area of poor positional structuring on one flank to the other, which happened to be much stronger in this regard with a low, diagonal pass across the pitch.

Rooney dropping deep also had the effect of creating space behind the Russian midfield. Essentially defending solely with two banks of four, Neustädter and Golovin were often left defending the centre of the pitch on their own. Due to Rooney’s and Dier’s ability to play penetrating vertical passes, if Russia’s central midfield players were to press them, they would leave a great deal of space behind them, between themselves and the defence.

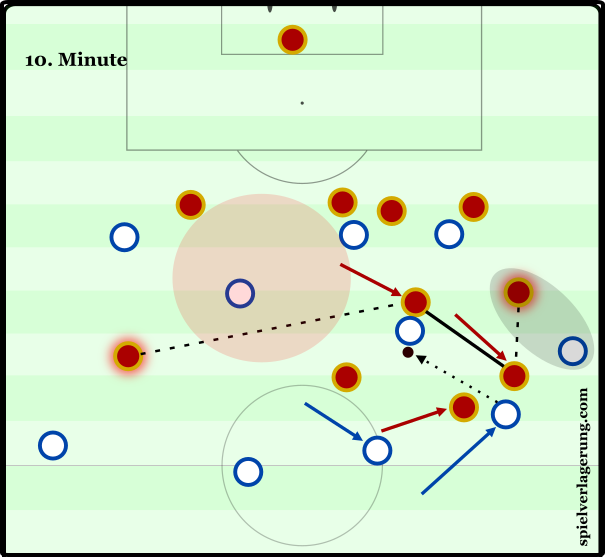

It was in this space that England had some of their best moments. Adam Lallana made frequent movements from the right flank into the halfspace, whilst Kyle Walker pushed up aggressively to draw the attention of Fyodor Smolov. With Georgi Shchennikov reluctant to follow Lallana into this area, and with Smolov preoccupied with the runs of Walker, this left the Liverpool man between units and between lines in Russia’s defensive block.

Russia’s fractured midfield line leaves an ocean of space for Wayne Rooney to receive the ball. Though the connection between Neustädter and Golovin is a strong one – with Neustädter taking up an appropriate position to cover his midfield partner – Kokorin on the far side has no interest in keeping compact in relation to the ball, leaving his teammates in a perilous position.

This movement was coupled well with Dele Alli’s advanced positioning. A similar tendency from Raheem Sterling on the left side would frequently leave England with an overload between Russia’s midfield and defence. In this situation, there simply weren’t enough Russian midfielders to block passes to all of England’s players between the lines, making it easy to shift them one way or another and pass to a free man.

This, when combined with Russia’s ineptitude against the ball led to some threatening situations. Their wide midfielders’, Aleksandr Kokorin and Fyodor Smolov, nonchalant approach to ball-orientations, left Neustädter and Golovin horribly exposed especially with switches between the halfspaces. Such switches engaged both central midfielders on one side, as the ball-near one would be man-oriented, whilst the ball-far one would be positionally-oriented – referencing his position primarily on the position of his teammates. Whilst this creates an area of local compactness around the ball, the lack of any subsequent shifts from the far-side wide midfielder would leave huge spaces in central areas for England to attack.

Russia’s Inability to Build-Up in the First Half

Russia had major problems with regards to their construction. This refers to Sbornaya’s struggles in building attacks rather than stadiums – although the latter is also an issue.

England in the first half were happy to let Russia’s central defenders have the ball. Defending in a 4-1-4-1 block with wingers slightly pushed up, there was no real pressure from any of their forward players as they sat in a rather low defensive block. The three central midfield players were only slightly staggered vertically, creating a large area where pressure could be applied to any Russian players receiving in the centre of the pitch. Horizontally compact, the England midfield three were able to threaten to intercept passes between them. Russia’s Spielverlagerung Hipstar – Roman Neustädter – in a typical display of tactical awareness, commented post-match that the team were aware that England would press well centrally, therefore they should avoid playing through the sixes.

Even so, this alone should not have restricted Russia in the way that it did when playing from the back. In a typical situation with Russia in possession with the central defenders and two central midfielders ahead of them, England would loosely cover the two midfielders in a man-oriented fashion, while Kane would use his cover shadow to block an easy pass into one of them. Systems which rely on man-orientations do not fare well when asked to deal with a player dribbling towards them. Such actions force the defending player to either let the player with the ball advance freely, or to leave the player they are orienting against to apply pressure. Neither Ignashevich nor Berezutski looked to force England’s midfield into making such a decision.

Instead, they took a more direct route. Long diagonal passes were aimed to the fullbacks who had pushed high up the pitch – disconnecting them from their central partners for the short option in the first place. However, both centre-backs’ distribution was uncharacteristically poor, with the usually reliable Ignashevich in particular struggling to complete even a handful of the many attempts he had at these passes.

Furthermore, even when the diagonal ball reached its intended target, Russia still had problems progressing the ball. With both central midfield players – and occasionally Oleg Shatov – primarily looking to receive the ball in front of England’s midfield, the wingbacks were more often than not completely isolated upon controlling the pass. This resulted in Russia being simply unable to progress the ball from their back line on their own terms. Consequently, Russia achieved barely anything of note in the first half, with Michael Caley calculating a first half xG of only 0.04.

Second Half Adjustments

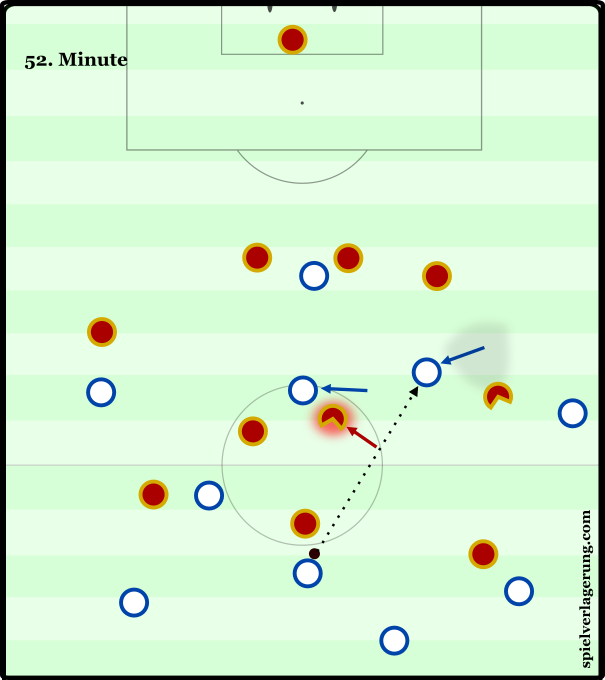

Come the second half, England took a much more proactive approach against Russia’s sterile deep possession. Looking to prevent Slutsky’s side from killing the tempo of the game through their centre-backs aimlessly passing the ball between themselves, they would look to engage them slightly higher up the pitch by pressing not only with Kane, but with one of the wide midfielders, in an asymmetric 4-4-2. Lallana was particularly successful in this regard, directionally pressing Ignashevich towards England’s left side, refusing him the option to open his body to the pitch to switch the ball to Shchennikov.

In a scenario illustrating England’s positional dynamics, Russia’s poor coverage of the halfspaces, and Eric Dier’s exquisite diagonal passing, Adam Lallana exploits Smolov’s preoccupation with Kyle Walker by emerging from his blind spot into a position vacated by Golovin at the behest of Dele Alli. Had Lallana taken this as his starting position, he would have been seen by one of Smolov or Golovin, who would have undoubtedly acted to prevent this very dangerous pass from reaching the England midfielder. Thus, one of the benefits of dynamic positioning – of arriving at a desired position rather than simply occupying it – is shown.

In doing this, however, England unintentionally aided Russia’s build up. By cutting off the option to switch to the fullback, the centre-backs were forced to play straighter balls towards Artyom Dzyuba. Dzyuba’s supreme ability to hold-up the ball under pressure from defenders allowed him to single-handedly create a platform from which Russia could launch attacks higher up the pitch. The lack of depth in England’s midfield line left large areas of space which Kokorin, Smolov and Shatov could pick up Dzyuba’s knock-downs and attack England’s back line directly. It was through this mechanism that Russia obtained most of their success.

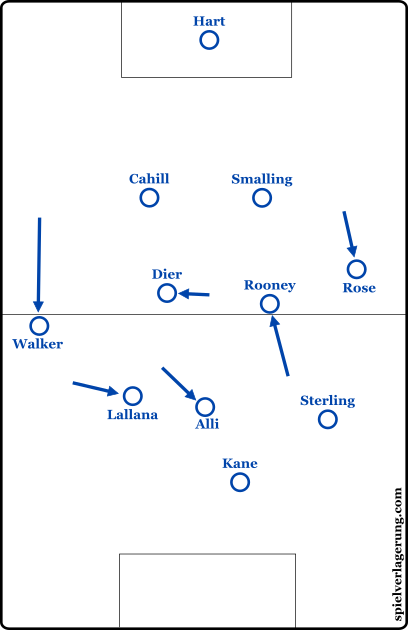

Meanwhile, England also adjusted aspects of their build-up play. Further emphasising their fluidity in positioning, they rotated to a back three in possession, with Walker starting in a much more advanced position and the rest of the defence sliding round. Rooney would occupy the left halfspace in this asymmetric 3-2-4-1, with Dier taking up the prime responsibility of linking the two strata of the midfield.

Due to Walker’s much more advanced positioning, however, England struggled to form connections on the right hand side. As a result, the Three Lions struggled to keep possession on that flank, as even Fyodor Smolov was able to block passes up to the England right back. Compounding this, Gary Cahill would often take the ball right out to the flank, limiting his passing angles considerably due to his proximity to the touchline. Adam Lallana also contributed to this poor positional structure, favouring the extremity of the offside line in favour of the positions he took in the first half in between the lines which enabled England to threaten Russia much more.

Igor Akinfeev, just starting to redeem his reputation in Russia following his calamitous error against South Korea in Brazil, kept Russia in the game with an excellent save from Rooney, but unfortunately for the 30 year-old, it was arguably another mistake which gave England the lead. Having previously “cheated” considerably by edging behind his wall for a free kick earlier in the half, Eric Dier caught the CSKA goalkeeper by surprise with a well hit strike into the unguarded side of the net. A goal that England no doubt deserved, but didn’t have to work particularly hard for.

With Russia throwing the ball up to Dzyuba at every opportunity, Roy Hodgson attempted to break up the flow of the game with some substitutions. Jack Wilshere came on in place of Rooney in the same role as the England captain, but with slightly different dynamics. While Rooney displayed a great range of passing in his deeper midfield role, he often turned away from opportunities to play dangerous, short passes to free players between the lines in favour of more glamourous longer passes to players on the flank. While such passes look spectacular, and give fans a great reason to stand and applaud their hero, they are often strategically lesser passes, as it takes the ball further away from goal, and into an area geometrically bounded by the touchline. Wilshere, when he came on, was much more vertical in both his passing and his movement, which caused Russia some problems. A particularly nice combination between him and Harry Kane was called back for offside, but epitomises what the Arsenal man brings to Hodgson’s side.

On the Russian side, Leonid Slutsky approached the last minutes with an entirely different midfield three than the one that started the game. Roman Shirokov – one of the finest players in Russia over the last ten years – came on in the attacking midfield position, whilst Denis Glushakov partnered Pavel Mamaev in midfield. Mamaev threatened to give Russia the same impact Wilshere gave England, with a glimpse of his penchant for creating and executing vertical passes which has made him such a hit at Krasnodar this season, without stamping his authority on the game as much.

Conclusion

In the end Russia were able to snatch a draw from the jaws of defeat. In a lapse of concentration, Berezutski was able to read Shchennikov’s intention to cross from a wider position before anyone else in the box, finding himself a space at the back post area, with only the diminutive figure of Danny Rose in his way – rising high above the left back with a great leap before finishing with a looping header over Joe Hart.

It was neither the ending England wanted nor deserved. Despite that, however, there are lots of positives for fans to take away from the game. England showed a tactical flexibility which has been absent in recent years, with promising young players playing prominent roles in Roy Hodgson’s system. The rules regarding progression to the knockout stage make it almost certain that England will move on to the next stage of the competition.

The story in the Russian camp is a different one. Although they had a nightmare of a month leading up to the tournament with regards to injuries to key players, Sbornaya will need to improve in almost every aspect of their play if they want to make a serious impression in France. To score a goal in the last minute from an xG of 0.2 is not something Leonid Slutsky can hope to sustain over the course of even the group stage.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

shadowchamp June 15, 2016 um 6:13 am

Thanks for the good analyse i hope england can archiev what they deserve … i like there style of play