Team Analysis: New York Red Bulls

*This article was intended for the site of the New York Red Bulls where I write opposition previews for their upcoming games. It wasn’t released due to the sensitive information in the article which could have potentially aided their opposition which is why you’re now seeing it on here.

It was written following the first 4 matchdays of the MLS season which is why I will be referring to the initial games throughout the article instead of more recent matches. Aside from the semi out-of-date analysis, keep in mind that the intended audience was not the average Spielverlagerung reader and this is reflected somewhat in the writing.

Under the guidance of new manager Jesse Marsch, the New York Red Bulls have made a strong start to the new MLS season as he has installed a new tactical system oriented around central control and a high press which has already caused the opposition significant issues in their possession games.

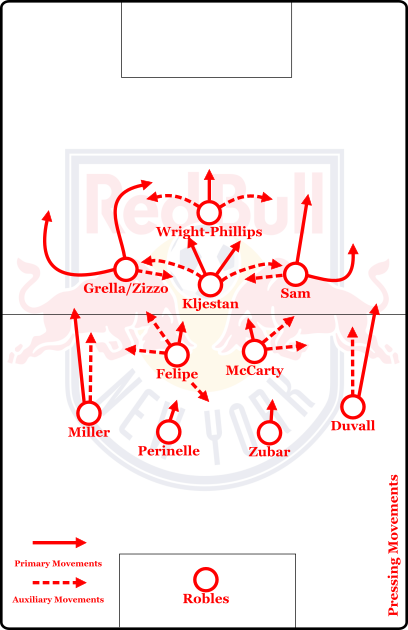

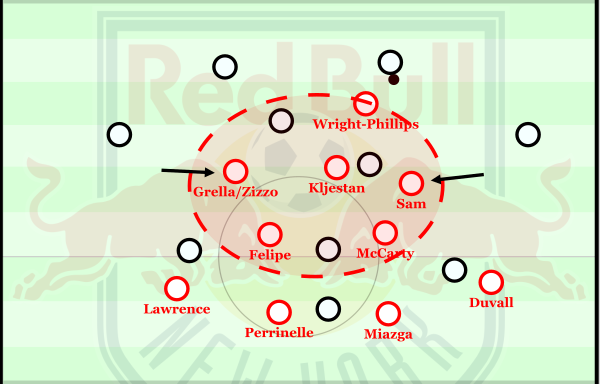

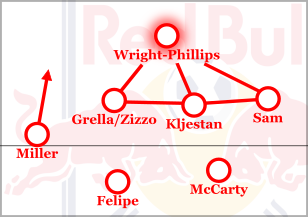

Without the ball, Marsch has his team lined up in a general 4-2-3-1 formation, which can become a 4-4-2 as Kljestan moves up alongside Bradley Wright-Phillips to support in their higher press. Such a shape is flexible when pressing upfield as essentially there are 3 supporting players behind the 1st presser who can adapt their positions in accordance with the demands of the situation.

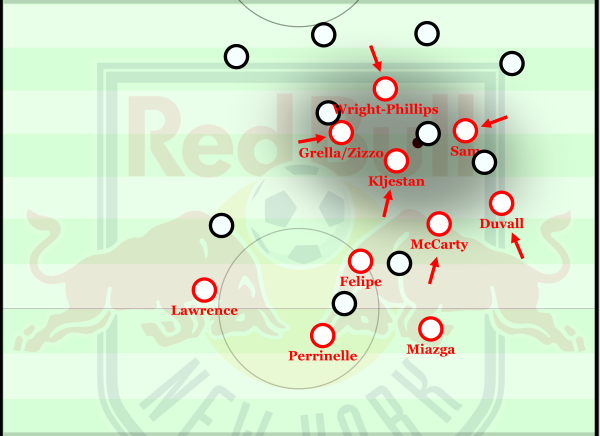

It is evident to see from the opening 3 games of the new MLS season that this factor has come into effect as the 3 of Sam, Kljestan and Zizzo/Grella have been paramount in the pressure on the opposition’s defence. This pressure comes in numerous shapes.

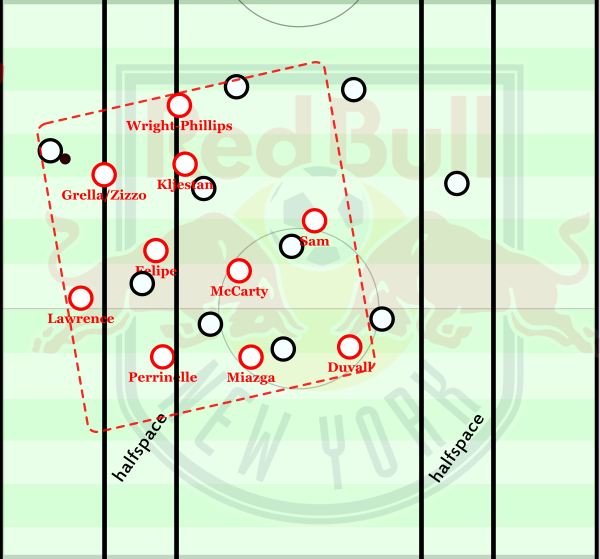

One common case of this is where situationally, a 4-3-3 shape is formed by the ball-near winger moving up to support in pressure.

In this shape, they can maintain a compact block when the ball moves wide, cover all the nearby options and control the central space which is vital, as Kljestan covers passing lanes into the middle of the pitch. As the ball-near winger moves higher, the ball-far one comes inside to sustain the balance in the shape, as he supports the midfield battle should the opposition find space to play a ball into that area

Pressing

Movements

The Red Bull’s pressing shape is of high flexibility, which translates into differing movements from the players both individually and collectively. With this feature of the new system, the team can adapt to counteract most situations during the opposition’s early possession game.

As shown in the above diagram, the roles of McCarty and Felipe are much more auxiliary during situations of pressing, where they only directly press the opposition in reaction to vertical passes from the opposition backline. Instead, their positioning and movements are often based on closing down the space behind the front 4, which alternatively could be exploited by the opposition. This is particularly the case in wide situations as they’re key in the defensive block shifting wide towards the touchline

The collective action of shifting is especially common for Marsch’s side, as they often allow the opposition to pass towards the touchline from a deeper position, as the space is a much weaker one to control than the centre.

In contrast, the wide players display their importance in the direct pressure of opposition defences, as they’re frequently required to press a centre-back moving wide as Wright-Phillips occupies the opposite one. Alternatively, they’re also key in the midfield battle due to their narrow orientation which allows them to situationally man-mark a defensive midfielder when necessary.

Patterns

Alongside the various movements which are a result of the newly-found versatility, many pressing patterns are apparent in Red Bull’s press. Most of these are orthodox of a standard 4-2-3-1 shape, whilst occasionally, some quite unique structures emerged as Kljestan and co. looked to up the intensity on the opposing defence.

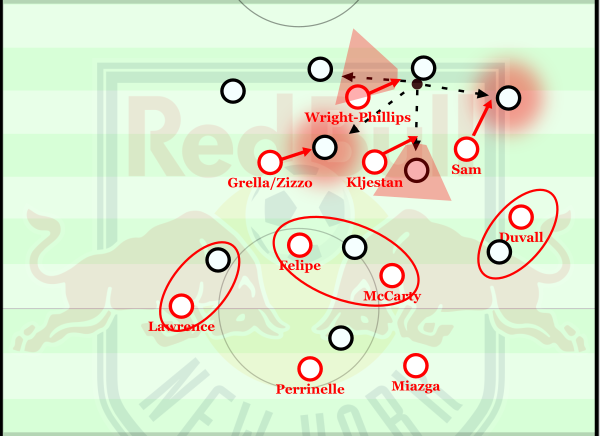

One of the most frequently used structures is during situations of wide pressing. This is partially down to the fact that the space offers less variation, as the team only presses from 1-2 directions whereas it is usually from any possible angle when the ball is central. The 4-2-3-1 formation allows wide pressing to be emphasized to great effect when pressing the opposition against the touchline, as the near 3 players in the front four tilt to cover any central lanes.

The role of the ball-far winger (in this case Grella/Zizzo) is quite important as a supporting player. By moving considerably narrower than the standard position of a winger out of possession, he offers to cut off any switch, whilst creating a 3v2 overload against the two opposition CMs which increases the likelihood of a regain significantly in the favour of Marsch’s team.

Similarly, the deeper CM can also have an important influence, albeit indirectly. Like his teammate on the left, Felipe in this situation can move up to create the same overload or otherwise shift across as well to increase the stability down the right of the pitch.

Pressing Traps

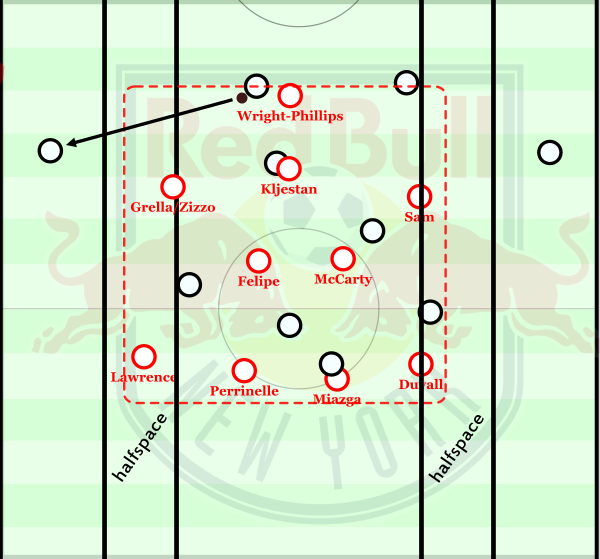

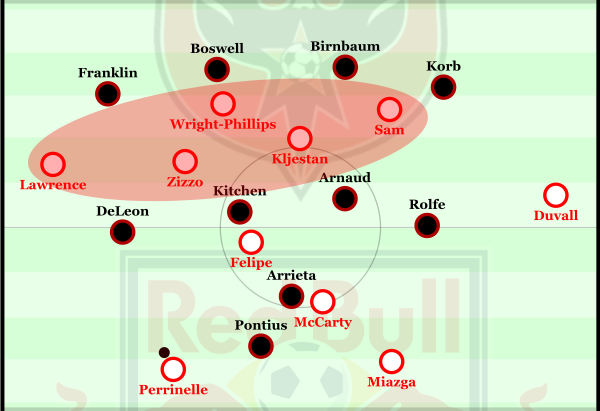

With the implementation of the new system, Marsch’s side are seemingly utilising pressing traps to enhance their ability of winning the ball in threatening positions high upfield.

Pressing traps are a relatively new aspect of defending, only becoming common during the past few seasons. They entail the defending team luring the opposition into playing a pass into a weak area of the pitch, as the defenders expect, who can then spring an intense pressure to force an error. One of the most common ways to do this is simply by marking all of the options apart from one player in a harmless area (a full-back on the touchline, for example), forcing the pass to the desired target, only for the near players to close down the recipient instantly.

However, the Red Bulls have employed a slightly different approach to the aforementioned case. Instead, their method is much more focused on the controlling of space, and not the specific players. The large majority of traps are formed to be executed in lateral spaces, as Marsch has prioritised the centre and half-spaces (space between the centre and the wide areas of the pitch). Through having all 11 of his players in a narrow shape, the opposition’s passing lanes into central areas are nearly always cut off, meaning that they often resort to passing wide. As soon as the pass is made, the team shifts across to suffocate the space around the player.

With quick ball-oriented shifts, the Red Bulls can effectively isolate the receiver of the initial pass.

With all the passing options cut off and the usable space being minimal, the ball-carrier in these situations is often left with few options. In this case the main two possibilities are a long diagonal ball into the centre, or a safe option back to the goalkeeper, which we both know will be pressed aggressively by Wright-Phillips.

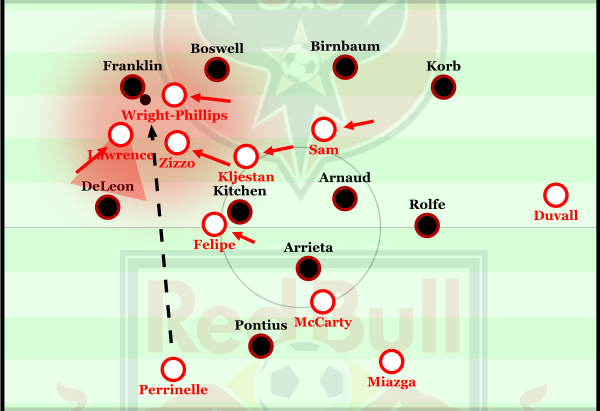

A more unusual approach to a pressing trap was on display against Columbus Crew in the 3rd match of the season.

In the first frame, Wallace stays slightly away from Finlay to allow Saeid to pass to him on the touchline. Meanwhile, the Columbus midfielder is being forced towards the touchline by the pressing of Felipe, McCarty and Kljestan as their movements direct the ball away from the vital central spaces.

Then, as Finlay receives the ball, the 4 Red Bulls players continue their press and close in on the full-back. However, he intelligently beats the press as McCarty and Kljestan struggle to close the passing lane inside to Grana.

The Red Bulls forwards react very well to this situation however, as then the four near players all press with great intensity to immediately destroy any usable space and cut off the key passing lanes. This then forces a regain after Grana makes a misplaced pass under the pressure of four onrushing Red Bulls players.

Pressing the Goalkeeper

For most teams, I don’t agree with the striker closing down such a long distance to the goalkeeper. In the majority of cases, their shape becomes weakened as he makes it a 9v10 battle in the centre of the pitch, increasing the opposition’s ability to win the second ball.

Because of the compactness which Marsch has instilled in his team however, this disadvantage is not exactly the case. This focus on compaction has led to the team having numerical superiority in nearly every situation, even when Wright-Phillips moves away from his teammates – it facilitates the striker’s actions whilst counteracting the negative consequence of it.

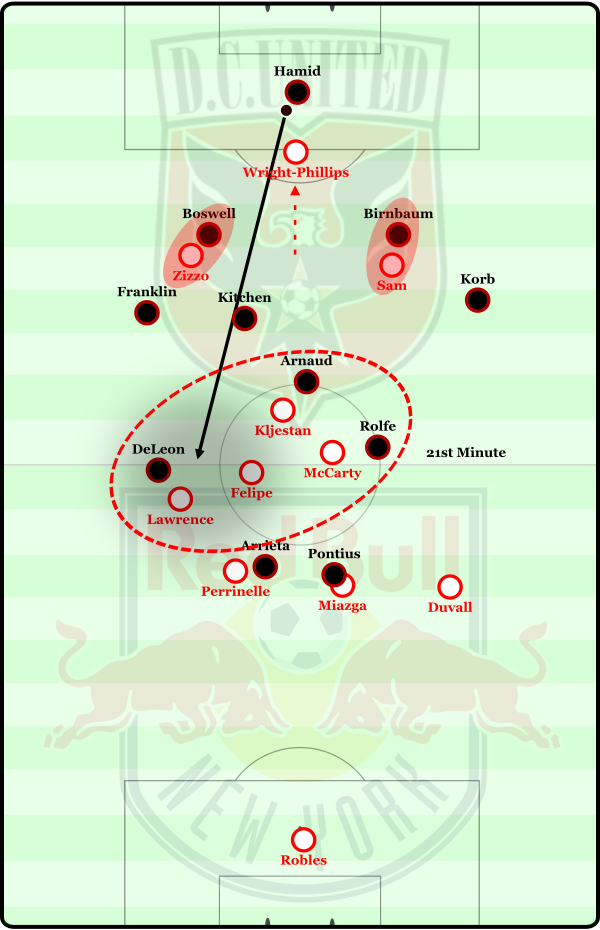

A case of this was shown in the game against DC United. In the 21st minute, Wright-Phillips pressed Hamid to nearly his 6 yard box whilst Zizzo and Sam covered the short options, forcing a long ball. With the midfield particularly compact, and the involvement of Lawrence advancing as he had no-one to mark, they regained possession. That being said, better intelligence from the DC players, particularly the two full-backs and Kitchen in midfield could’ve seen them come out on top following the long ball.

With RBNY’s compact midfield, Wright-Phillips can press the goalkeeper into a long ball where the Red Bulls have a heightened chance of regaining possession due to the central numerical superiority.

Early Issues with Impressive Recoveries

Unsurprisingly, the team’s pressing isn’t perfect yet, and in one or two cases there has been a mistake in the pressing, where someone has misjudged the distances and got caught out when trying to intercept a pass, for example. In a lot of teams who are new to a focused pressing game, they would likely lose balance in the structure and struggle to recover a stable organisation.

However, whether it be due to some impressive coaching from Marsch, or simple good game intelligence from the players, this has rarely been exploited against Red Bulls. Upon such moments, the deeper players made concise movements to balance out the structure and destroy any space which could potentially be taken advantage of.

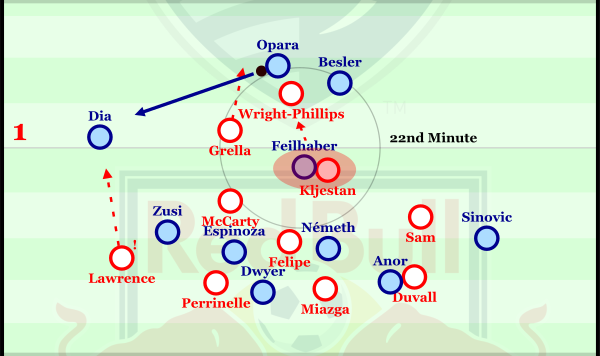

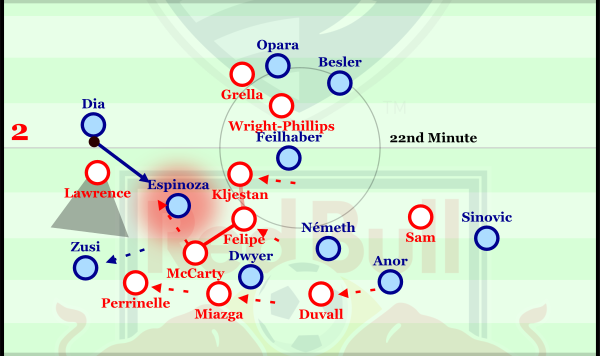

An example of this can be seen in the 22nd minute of the opening game against Kansas. Here, Grella misjudges the distance from him and Opara, and he loses out on the challenge, leaving the left flank exposed.

However, Lawrence reads the situation well and pushes up to close down the space which otherwise, Dia could drive into. Meanwhile, the defensive line shifts across to keep a ball-near compaction (high number of players on the third of the pitch where the ball is) and to stop Zusi from being able to move in behind the advancing Lawrence.

Lawrence cuts off the option of Zusi in his run, whilst the trio of McCarty, Felipe and Kljestan close in to cover any passing options and the two highest players stop any possibility of a pass backwards. In this situation in particular, it is McCarty who presses with the greatest intensity and he challenges Espinoza as he recceives the pass, leading to Felipe regaining the ball behind and a potential counter-attack for Red Bulls.

Such intelligence to react efficiently to scenarios where they’re weak, following their strategy not going to plan, is very promising. It suggests that Marsch is training the side’s pressing in good detail to ensure that they cannot be exposed as they’re still learning. Meanwhile, the situations where players have to move away from their natural positions, such as Kljestan dropping above is a display of the great versatility that is a characteristic of a number of players in the team.

Poor Opposition Adaption

One could argue, that opposition teams have adapted poorly and often maladaptively when facing against Red Bull’s rather unique defensive strategy. This could potentially be a result of not being able to scout them beforehand in much detail since they haven’t played many games in the system yet, or because the pressing is relatively unseen in the MLS before.

Regardless of why they are making the poor adaptions, it certainly makes the likes of McCarty’s job easier, as the opposition put up little fight when being pressured high up the pitch and this has led to regains in dangerous positions numerous times already.

By being tactically superior and more advanced to the majority of MLS teams, the Red Bulls’ have a strong advantage over their opposition which they should look to exploit for as long as possible, until the other teams devise more appropriate gameplans.

Fatigue

Like every side that makes a sudden move towards a high-intensity system, the NYRB have evidently not adapted physically (yet) to the demands of Marsch’s system. This is not a criticism of the Red Bulls, given that there is no team that has successfully coped with the change immediately. Even this season, it has been the case with both Marseille and Bayer Leverkusen, whose new managers went a similar route to Marsch in relation to defensive strategies.

Understandably, this was particularly the case in the first game against Kansas, as the pressing declined slightly from the 60th minute onwards. This was less of an issue in the two following games, presumably as the side are moving towards full match fitness which is definitely a promising sign given the energetic start to the season already.

Counterpressing

Marsch has also looked to implement counterpressing into his pressing system and has already produced some sizable results in the 3 games played so far into the MLS season.

By pressing the opposition immediately following the loss of possession, the team aim to regain the ball when the other team lack stability in their shape. The process is supported by the fact that Red Bulls attack often with high numbers and in a narrow shape, meaning that when they lose the ball there is often 3-4 nearby players to enforce an immediate press.

The counterpress allows a team to also continue their momentum in an attack and restrict the defending team from resting after winning the ball, as they often struggle to cope which the rapid reactions of the opposition.

Teams such as Barcelona and Borussia Dortmund, whose counterpressing was considered amongst the best in the world, put in great effort to train the mechanisms to be instinctual. This worked to reduce the transitional time from losing the ball to pressing the opposition to be almost non-existent, as players could be seen making the movements before the ball is even lost at times. More issues can be then caused for the opposition, as they have minimal time to react upon regaining the ball and are even more susceptible to losing it in dangerous locations.

An important tactical aspect of counterpressing is the blocking of the centre of the pitch. From the middle, a player has a greater range of possible movements and passing options, thus a more intense press is required during these situations. Also, the pressing team must direct the player away from the centre of the pitch and arch their runs to shut down as many passing lanes as possible.

Ideally, the player would be forced towards his own goal also, forcing him to play either sideways or backwards passes. This reduces their ability to exploit the space left open in deeper positions as the midfield presses higher, which could be opened up with a simple vertical pass forwards.

Coaches sometimes have issues in the details of implementing a counterpressing system. Namely the questions of “how long should you press for until retreating?” and “how intense should the press be?”. The difficulty in implementing this aspect of defending is difficult as it is very dependent on the positioning off the ball which can vary massively, meaning that multiple different approaches need to be trained. To solve this, many use the commonly-known 5 second rule – where the team press at full intensity for 5 seconds after losing possession, if they don’t regain the ball within that window then they retreat.

Stopping Counters

Considering the risks of attacking with a large number of players, counterpressing also serves to minimise the possibility of an opposition counter-attack, as they look to stop it before one can take form. This was a key aim in the counterpressing of Guardiola’s Barcelona, as they attacked with so many players, leaving them unstable upon losing the ball. Especially when both full-backs bomb forward, Red Bulls have used this technique to stop any opposition counters already in the first 3 games.

Counterpressing Type

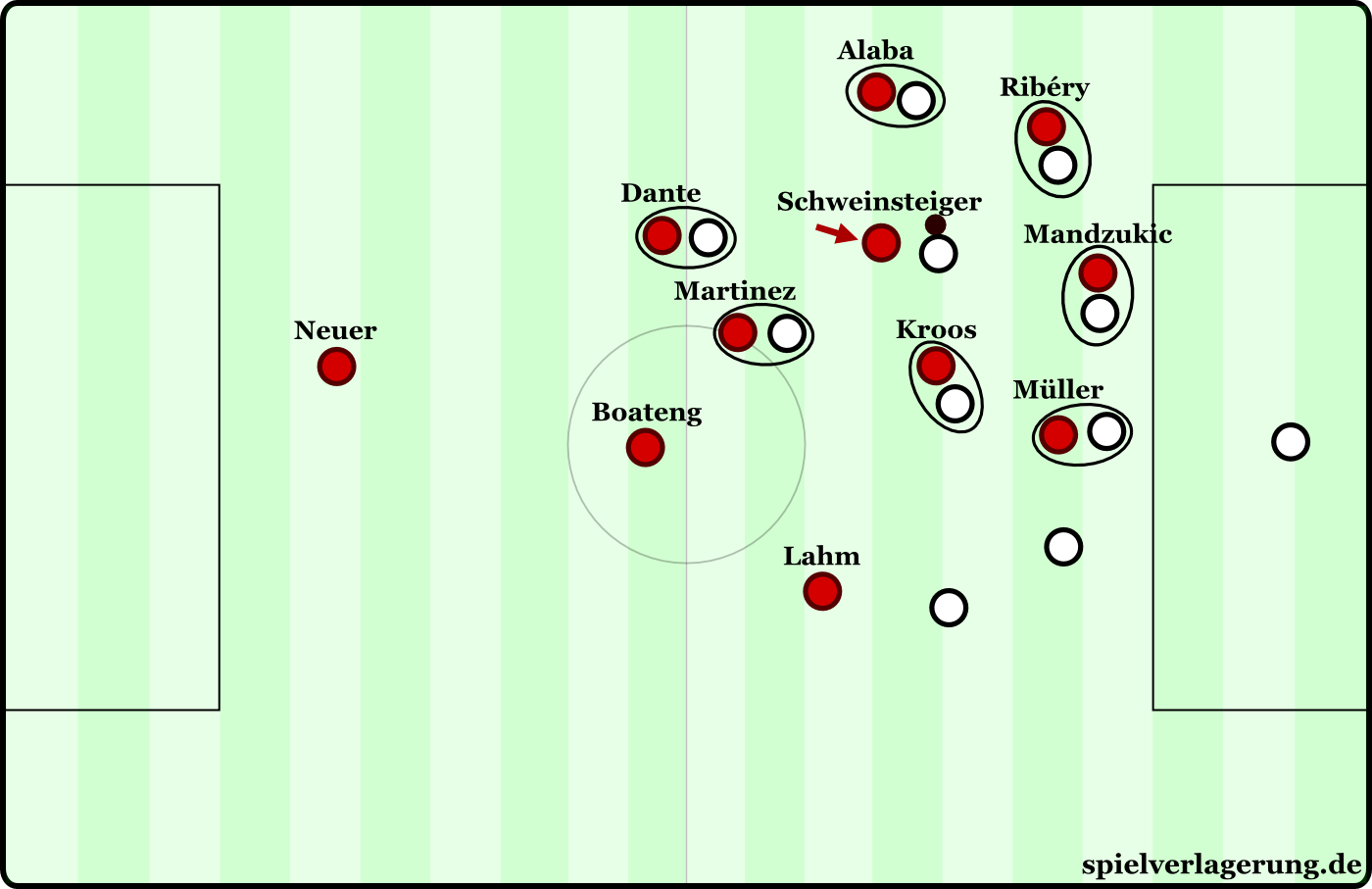

When a team counterpresses, they can do so in a number of different styles and orientations. A common one is man-marking based, where a team will simply mark every nearby player, with one pressing the ball-carrier. Jupp Heynckes’ Bayern Munich side used this to great effect, especially in their excellent season which included the 7-0 victory over Barcelona (over two legs).

When it comes to the Red Bulls however, their use of counterpressing is somewhat inconsistent, or mixed. They don’t seem to use a set method but instead I’ve seen them take multiple approaches, whether this is unconscious or just a situational approach I can’t say.

One case of this in its most interesting form, was a mixture between passing-lane coverage, and the above man-marking.

In this case, it seems like the individual makes the decision as to whether they should man-mark or cut off the passing lane, by where their starting position is and what the best approach from there is. This is quite unusual, as a team usually has an organised mechanism in their counterpressing based around a certain approach.

Perhaps the most common form of counterpressing for Marsch’s team is oriented around closing the space around the ball-carrier, the type which led Klopp’s Dortmund to win the Bundesliga in consecutive seasons. It could be considered a more simplistic approach, yet is still very effective. As the players close down the space around the ball-carrier, most passing lanes are automatically cut off purely due to the defenders’ proximity to the ball.

It is highly possible that Marsch has not specifically looked to work on this form of counterpressing, yet instead it comes naturally as the nearby players have developed the near-instinctual reaction to close down the ball. However, it is not a pure ball-oriented approach where they simply run towards the ball gung-ho style, as they still maintain their shape to some extent, as you can see in the diagram above.

Compactness

“Defending is a matter of: ‘how much space must I defend? If I have to defend this whole garden, I am the worst [defender]. If I have to defend this small area, I am the best [defender]. Everything is about meters. That’s all” – Johan Cruijff

By the above quote, Cruijff states that defend is based about how much space an individual and a collective have to defend. If a player has to cover a large amount of space, then he can easily be beaten (unless he is Sergio Busquets), whilst if the same player has to cover 1/3rd of the space, then he becomes a very strong defender. This has been a key principle in many great teams of the past, such as his Barcelona team which positioned too bad defenders in Ronald Koeman and Pep Guardiola in the heart of the defence.

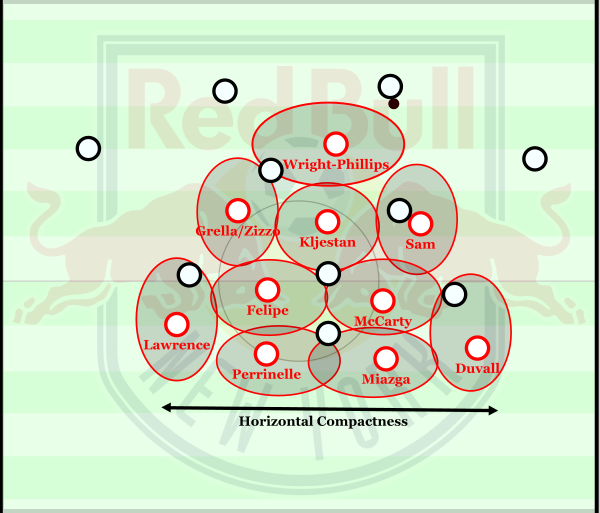

Marsch is having a similar influence with this ideology at the Red Bull Arena, where the narrow structure of Red Bull’s defensive block is a key feature of their defensive strategy.

As the 4-2-3-1 shape has great horizontal compaction (short distance between the two widest players), the spaces that the individual has to defend are much shorter than average, so they become much more effective.

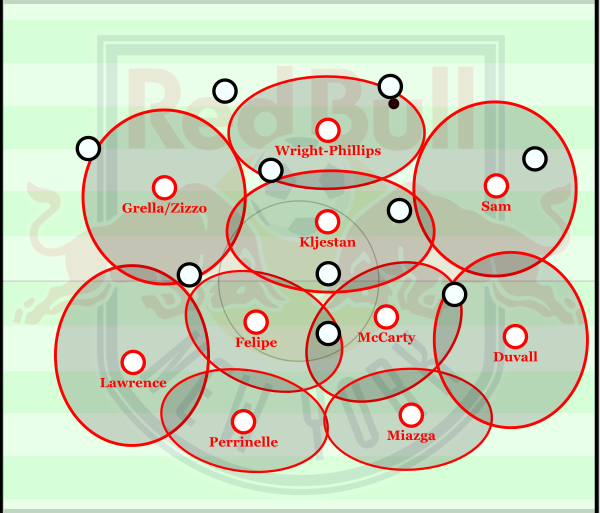

In the above diagram, this would be approximately the amount of space each player would have to defend and control, if they were in a 4-2-3-1 shape with no regard for the distances between players nor an emphasis on compaction. Unless the opposition that they were defending against are of a considerably worse standard, it is highly unlikely that they will be able to defend effectively, making the whole block relatively weak. The opposition players have great amounts of room to utilise both centrally and in lateral spaces, as many passing lanes can be opened with ease.

However, the New York Red Bulls are very good in their levels of compactness, and as the team stay narrow and close together, the spaces which each individual (and thus the whole block) has to cover, is much smaller than most teams. With smaller spaces to defend, they can do so to a much better effect with structurally much less weakness and minimal spaces between players which the opposition would look to exploit.

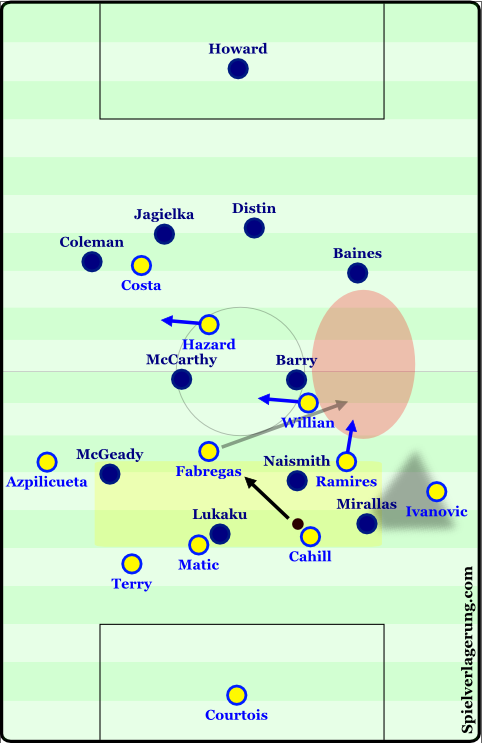

In the new system which Marsch has developed, the Red Bulls are, tactically, superior to a number of Premier League teams in regards to aspects such as pressing and particularly compaction – which is a significant issue with most teams. Take the below example from a game early in the season between Everton and Chelsea. During the build-up to the 2nd early goal, notice how far the distances are between both the centre-backs and the striker, and the two widest players. Because of this, the spaces which opened up are enormous which the likes of Hazard and Fabregas exploit with ease and create a 2-goal lead within the opening 5 minutes of the game.

With great horizontal compaction (short distances between the two widest players) in particular, they assert a great control over the space they’re covering, given the significant numerical superiorities formed. This is especially key in the centre of the pitch, which is something I will discuss in greater depth within the next article.

Vertical compaction is also key, and particularly the distances between the defensive line and central midfielders has improved from the opening game, which showed slight issues when the space between was exposed.

Although it is perhaps not as radical as their compaction horizontally, the short distances between the lines of players is very important and truly facilitates their ability to press high up the pitch.

With minimal space between the lines, should the opposition manage to move the ball into the defensive block then the players will have minimal time to produce anything and have a high chance of losing possession.

If you see the diagram above from the Everton – Chelsea match, there is around 55 yards between the defensive line and Lukaku, meaning that Chelsea can easily pass the ball with time and space to work between the lines of pressure. On the other hand, there is less than half of that distance in the image from the DC match, where the opposition failed to circulate the ball through Red Bull’s defensive block.

The positioning of the wide players is especially key, as they essentially are what makes the midfield so compact horizontally. In most teams, especially in England, the wingers have a very simplistic role of man-marking their respective full-back. This can then be exploited rather easily, by opening passing lanes or forcing the defense into a 6-3-1 which has poor control centrally.

It is therefore refreshing to see a team use their wingers in a different and much more effective way as they influence the game to a much greater extent when supporting the midfield shape better, instead of often becoming isolated out wide.

Control of Space

The focus on maintaining a compact shape, has led to the Red Bull’s holding a strong control over the centre of the pitch both with and without the ball.

In many sports, the centre of the playing area carries great importance, and every team should look to control said space. This theory has been put into practice by various managers in their repositioning of key players, Gareth Bale was moved from a left wing position to the centre of attacking midfield by Andre Villas-Boas, whilst the greatest example is Lionel Messi. Before becoming the best player ever, the Argentine had been used on the right wing by Frank Rijkaard and at the beginning under Guardiola. Then, during a clasíco match Pep gave the nod and Messi switched positions with Eto’o, wreaking havoc amongst the Madrid defence from the middle of the park.

By controlling the centre in possession, you are in an optimal position to attack from, as you can access any space ahead of you with at times just one pass, just like a piece in the centre of a chessboard maximizes the number of squares it can access within one move. Therefore, important actions in an attack such as changing the direction are at their most effective when the team has a control of the centre.

This then results in a more potent and unpredictable attack, given a greater wealth of options available. Attacks down the wings are often much more linear in terms of aspects such as passing, movement and positional play which in turn equates to them being more easily defended against. On the other hand, central attacks generally have a greater complexity which is more often than not, harder to stop.

In addition, the central player in possession maximises the degree of direction he can move into. When a player has the ball on the touchline, there is only 180′ of direction in which he can move into, as the touchline cuts off half. This is a massive disadvantage as it makes pressing much easier, in contrast to the 360′ of movements available from the centre and half-spaces (between centre and wing).

Given these benefits of central control, it is vital that the team dominate in the middle of the pitch both in and out of possession, to take advantage of the above aspects but also to prevent from the opposition from doing the same.

By controlling the centre without the ball, a team can restrict any crucial passing lanes from deeper positions, which can otherwise be used to penetrate the midfield and access the attackers in dangerous spaces infront of the defence.

Although they relinquish coverage of the wide areas, this is not necessarily a disadvantage. Firstly, it invites a team to circulate the ball into those spaces which are much less threatening. One reason for this is simply that the goal is in the centre. The attacking strategy of crossing the ball is extremely inefficient in comparison to approaches from central areas, as statistical analyst Michael Caley (@MC_of_A on twitter) showed in one piece that headers or cross-assisted shots have a 25%-50% lower conversion rate from other shots from the same areas. Most teams are therefore happy to let the opposition cross the ball, especially when the defending team are compact and can flood the penalty area to make sure they intercept the crosses.

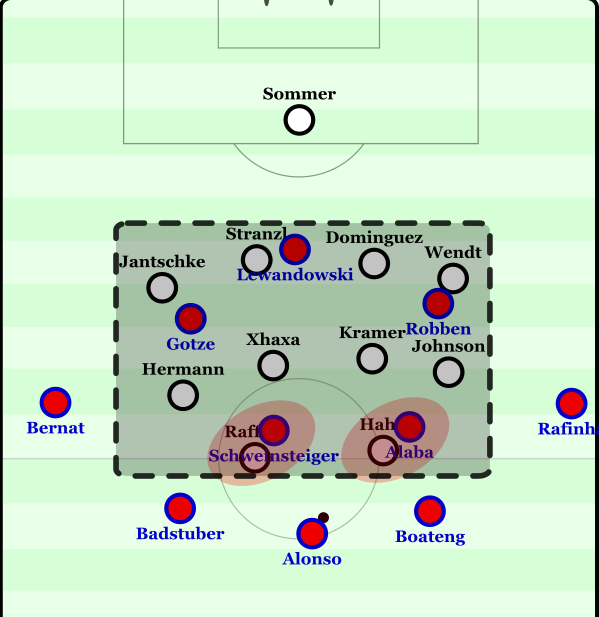

The importance of the centre was easily displayed in Borussia Mönchengladbach’s victory over Bayern Munich. Lucien Favre’s team are renowned for a compact 4-4-2 which overloads the middle of the pitch to deny the opposition access, forcing them to go through the wings. Bayern’s attacks were completely ineffective and predictable as they as they had no central force whatsoever.

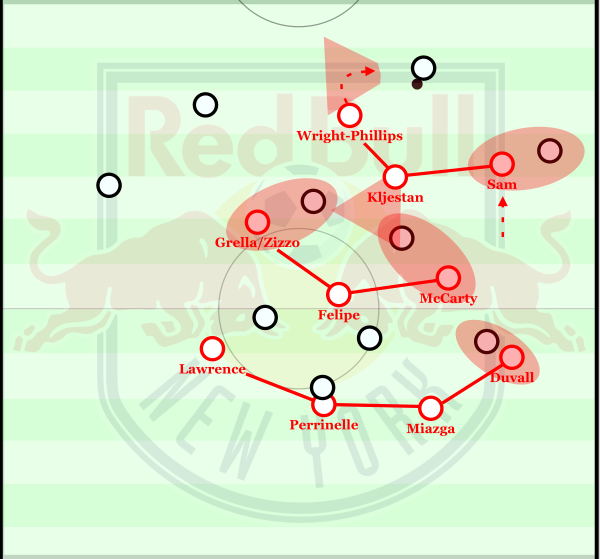

The role of the two wide attackers for the Red Bulls are key in their control of the centre of the pitch. Their narrow positioning is vital in the control of the centre as their presence helps overload the midfield, especially in higher positions alongside Kljestan. This can be seen in the below scene where Grella supports Wright-Phillips in the press, whilst Sam is nearby on the Kansas 10.

Given that the central midfield battle of two orthodox 4-2-3-1’s is an equal 3v3, the wingers make all the difference as they overload it into a 5v3 in the favour of the Red Bulls.

The presence of the wide players ensures that no central passing lanes are available to be used, forcing the opposition to move to a wide position, whilst they also supported in maintaining a compact block whilst pressing the centre-backs also.

Attacking Organisation

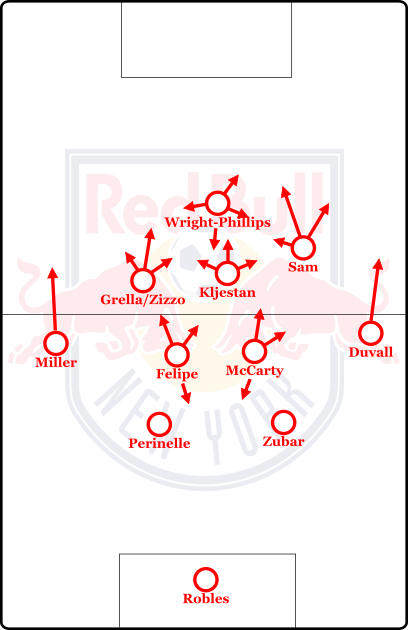

Marsch’s ideologies of a high pressure game plan with great speed in their play translates seamlessly into their attacking strategies. It is based highly on central play with great speed in combinations between the front four, with support from the central midfielders and full-backs.

Through the narrow 5 in midfield, they can at times easily circulate possession through the middle of the pitch, creating valuable overloads inside the opposition defensive block. This creates many threatening situations, where a free player can receive a pass to drive into unmarked.

One way in which they look to exploit these overloads is the through of vertical passes. This particularly looks to take advantage of poor opposition compactness, as they attempt to overload the space between the opposition defensive line and midfield.

The counterpressing in the transition to defence also facilitates this attacking strategy. In the above situation for example, the large numbers high up means that if the ball is lost, then the counterpressing will ensure extreme pressure on the interceptor. This could easily lead to regaining the ball, increasing the potential for an attack as the opposition are destabilized in the transition.

Their attempts to overload the 10 space (between the defence and midfield) is easily highlighted in their development of possession from the defence. A lot of teams now, especially in Europe, have one of their central midfielders (usually a single defensive midfielder) drop in between the centre-backs who move wide, whilst the full-backs push higher – this is called Salida Lavolpiana.

However, Marsch doesn’t have his team do this and instead, both McCarty and Felipe stay high in more advanced positions (although in rare occasions one will drop). This has the effect of supporting the numerical overloads higher in midfield, as a player isn’t sacrificed in dropping to be level with the ball’s position. Basically, instead of passing to 4 players in the centre, they have 5 options which can make a big difference in utilising the numerical superiority.

The combination plays within the central 6 are one of the highlights of the new system in possession. With the narrow shape, the players can make short combinations of passes at a tempo often too high for the opposition to react to, leaving them disorganised as they break through the middle.

Wright-Phillips is key in these moments, as he often drops slightly deeper or to the ball-near half-space depending on the position of the ball. From here he can make wall passes and help improve connections between the ‘3’, especially as they can sometimes move in a straight line which isn’t good when the ball needs to be circulated between them. Because they would only be able to pass horizontally through the ‘3’, the movement of the ball becomes predictable, whereas Wright-Phillips’ presence allows for the possibilities of also vertical passes and diagonal, which a combination of is much harder to stop.

Similarly with the defensive organisation, the roles of the two wide attackers are key. Because of their narrow positioning, they often drift into pockets of space in the opposition midfield to receive passes in dangerous positions to attack the defence. This has been the case in particular with Lloyd Sam, who alongside Wright-Phillips has made an explosive start to the season in this position.

Conclusion

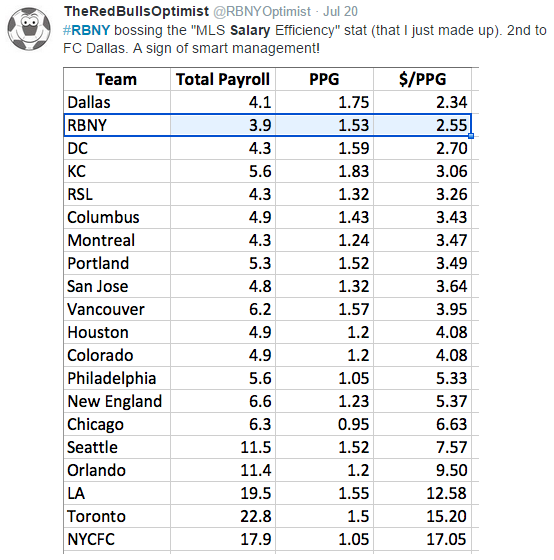

With what is becoming common across all teams of Red Bull, Jesse Marsch’s team are developing an exciting system based around their high block and compactness without the ball and their vertical-orientation and pace with it. Although it is unlikely that they won’t reach the excellent performances of Roger Schmidt’s Salzburg, the New York Red Bulls are performing well in MLS with a relatively fresh system under one of the lowest salaries in the league. Under Marsch, they will only continue to develop in the system in what is an exciting future for RBNY.

With what is becoming common across all teams of Red Bull, Jesse Marsch’s team are developing an exciting system based around their high block and compactness without the ball and their vertical-orientation and pace with it. Although it is unlikely that they won’t reach the excellent performances of Roger Schmidt’s Salzburg, the New York Red Bulls are performing well in MLS with a relatively fresh system under one of the lowest salaries in the league. Under Marsch, they will only continue to develop in the system in what is an exciting future for RBNY.

4 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Handyortung September 2, 2015 um 7:11 pm

Once the two highest pressers, Lampard and Villa, were bypassed they struggled to recover their positions as the ball movement by the New York Red Bulls was often just too quick. This caused severe issues for Kreis’ side at times as it left the centre of their midfield exposed and with players such as Grella and Sam coming inside, potential threatening overloads could be created.

TP September 3, 2015 um 11:17 pm

Hey, that is an excerpt from an article I made on the RBNY website?

SoccerCaptains August 6, 2015 um 2:15 am

Incredible piece. Very well done!

Yojo August 3, 2015 um 5:52 pm

“It wasn’t released due to the sensitive information in the article which could have potentially aided their opposition …”

Very weak performance. When I notice one is doing such a fantastic job, I would hire rather than censore him. JMHO. Btw, a really fantastic piece.