Man Coverage / Man-to-Man-Marking

The two most prominent methods of coverage used in soccer today are man and zone. In this article we’ll explain the different types and characteristics of man coverage as well as their advantages and disadvantages.

The Basics

“If you mark man-to-man, you’re sending out eleven donkeys.” – Ernst Happel

Man coverage was by far the most frequently practiced style between the ‘20s and ‘50s. Beyond this and into the ‘70s it was still somewhat practiced, but experienced a rebirth in the ‘80s. The chronological beginning and ending of these phases differs from country to country. In Germany, it was standard to man-mark opponents until the late ‘90s and beyond. Because of this trend, BVB took one in the nuts against Bayern in 2001 and German football by extension experienced a crisis across the board.

That being said, teams have always strived to have a strong man coverage. As we shall see, there are many varieties of man coverage and none of them are standard.

Before you go into a tactical or even a philosophical debate about football, you should familiarize yourself with the different variants of man coverage.

Collective man-marking

Option 1: Strict man-marking / number marking

Strict man-marking, or what I’d call a classic or rigid man-marking is probably the best known method. You should be close enough to your mark that if he had too much to drink the night before, you’ll know from the smell of his breath; and, should he need to puke, you can hold his hair for him. Whether knowing the exact level of an opponent’s intoxication creates a tactical advantage or not is impossible to say. Lilian Thuram is said to have rubbed himself with onions in the run-up to games to confuse his opponent.

Number marking: Everyone has a direct opponent, die strikers are free and there is a Libero / sweeper / covering player

In the end, man coverage comes down to one thing: each player is more or less tasked with following a specific opponent for 90 minutes. The sayings “if he goes to the bathroom, you should follow him” or “he needs to feel your breath” come from the primitive days of football. These represent the aggressive variant of this style. Herbert Chapman, the so-called “inventor of man-marking” at Arsenal in the mid-20s, installed a loose man coverage. It was sufficient if a player kept their opponent in sight and close enough to have instant access to them.

From a tactical perspective, the implementation of man-marking is simple: the daily bread of of the defender’s circuit class is, thanks to this simple statement, merely a matter of disciplined and physically stressed tracking.

Football professor Ralf Rangnick described this method as “number marking” because the opponent was tracked across the pitch by the number on the back of his shirt.

With time (and good trainers or intelligent players) this was, of course, adapted. In the finale of the 1975 European Super Cup final between FC Bayern and Dynamo Kyiv, Dettmar Cramer set his marking in line with Kyiv’s changes; the right-back, the six, and the left-back exchanged, the strong defender Joseph White now covered the outside-right Slobodyan, while in the National Champions Cup final he had taken the more central Billy Bremner out of the game. Assignments were no longer limited to marking the opposite position but to finding a suitable marker for the opponent’s key players (often at the expense of their own offensive game).

The advantages of rigid man-marking are also clear: simplicity, no communication problems when passing and moving, no special tactical training, playing off an ideally superior athleticism, and a continuous focus on the opposition’s key player.

The tactical weaknesses, in turn, are also at hand. These weaknesses were particularly apparent in games against fluid and flexible attacking lines, especially versus the golden team of Hungary in the early 50s, called “Aranycsapat” in Hungarian. The Hungary vs England match at Wembley in 1953, where the hosts went down 3:6 against the underdogs from the continent, was a key game.

The problem was not the obvious, i.e. the tracking of the opponent and the resulting opening of space, but something else entirely. Jimmy Johnston basically held his position and didn’t track Nandor Hidegkuti at all.

The opponents were ultimately got more right, which probably had to do with the fact that Winterbottom and Johnston had discussed how to deal with Hidegkuti before the game – with the following effect: they decided that Johnston should not track him, as Sweden had done successfully, but that they should use someone from the midfield, probably the left halfback in the 3-2-2-3. – RM

The English were neither surprised nor clueless – they were simply powerless. Hidegkuti had no trackers and set up overloads and combinations; England was shot down. On May 23, 1954, there was a return match, and in an effort to avoid making the same “mistake” the center-half tracked Hidegkuti. The result speaks for itself: England suffered an even bigger 1:7 defeat.

If you play with a collective number cover / strict man-marking, then there are many simple ways to cause problems. The opponent can move his marker to open spaces. He can switch positions to cause confusion, fall back and then destroy the enemy formation so that a hole can be created, or lose his opponent and skillfully produce overloads in targeted spaces, à la Hidegkuti.

A good tactical player can also carry their opposing marker to another defender, open space between them, twist around his opponent and, with the advantage of space and speed, directly infiltrate the channel. Even with a free roaming zonal defender behind a man-marking defensive line it’s possible, if only indirectly: you just open space on one side for a teammate via the movement of the Libero, which allows an attack. Afterwards, the attacker pulls with a twist inwards and may intervene or combine in the attack game.

You can see that the playing out of this folly is both collectively and individually unlimited. However, there were – in addition to the free man behind the defensive line – further solutions, which led to a second major variant in marking.

Variant 2: Flexible Marking

Flexible marking or, as I like to call it, transfer marking refers to a twist on number coverage. In this variant, the opposing player is tracked but handed over to another player when possible. This allows a team to better handle two opponents swapping positions, e.g. two strikers crossing over each other, but communication problems can pop up.

In the lower divisions of amateur football, for example, it is often not communicated when an outside player moves to the center and thus he is suddenly left without an opponent. In rare cases, one player pursues his man while a teammate tries to take the transfer; then there are two men on one player and the strike partner of the doubled up players is left laughing to himself.

All in all, this is the most commonly practiced variant of collective man coverage today and provides a logical progression. The opponent can not only be passed on to other players, but also into space.

This grew in practice in the early 70s under Dettmar Cramer at Munich. If the opposing players came forward to create overloads, they were tracked and then passed on to a teammate. They could then transfer this opponent into space. Because of this, Bayern were deeper and more compact, while the free opponent was stuck behind a tight defensive unit, which made the generation of overloads somewhat difficult.

With this style a kind of pressing is also possible. The opposing defenders are not man-marked and the zone covering offensive players in their team play deeper. They then support the isolated, ball oriented man-marker when he is attacking his opponent, or can take over a man freed by the the defensive marker.

This was practiced continuously but never really organized. Normally, the offensive player was exempt from defensive duties. The defensive players played in man coverage and the opposing defenders were marked only when they went on the offensive.

Nowadays, man-marking transfers are used all the time. A priority is placed on enemy counterattacks over man-marking the striker in the penalty area. The logic behind this is that the space is already open but the opponent doesn’t have much of it. That’s why situational man-marking is the only effective approach.

Otherwise, this collective man-marking variant has largely died out and is only used individually, which we will come to soon. Before we close the chapter on collective man-marking we have a third variant.

Variant 3: The space-oriented man coverage

This last variant, the space or zone-oriented man coverage is still used sometimes in the Bundesliga; by Dieter Hecking at his former club1. FC Nuremberg and others.

Here the team is often in a position-oriented spatial coverage, which we will cover in another article. From their positions they have a certain amount of space to cover. If an opponent strays into in this space, then he will be man-marked.

If the opponent leaves the opponent’s space without the ball, then the player moves back to his original position in the formation. This is, in some ways, a compromise between man and zone defense. The team is set up in a compact space-covering array and uses it to cover their targeted man. The opponent should be tightly covered and pressed when receiving a pass while the rest of the team ensures there are no open spaces.

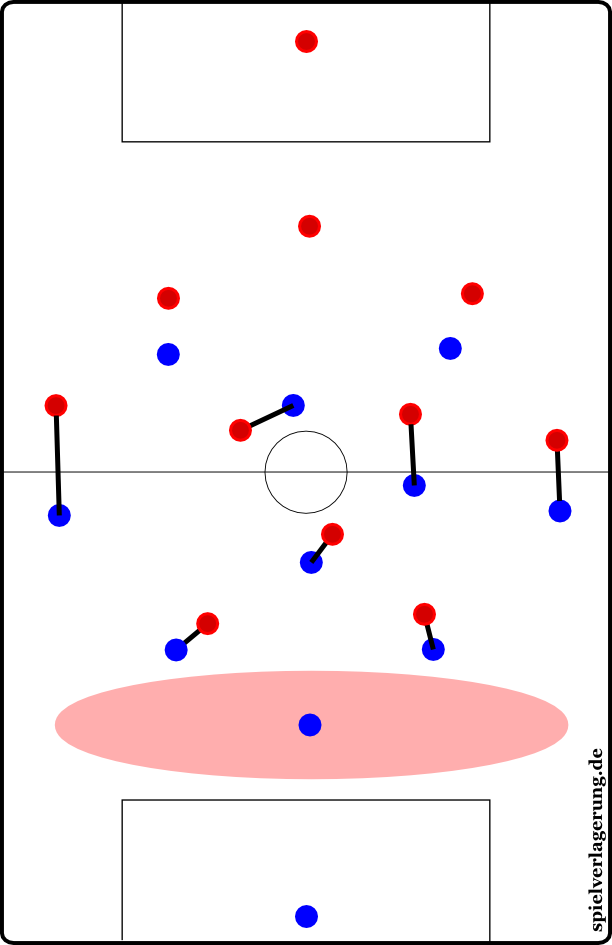

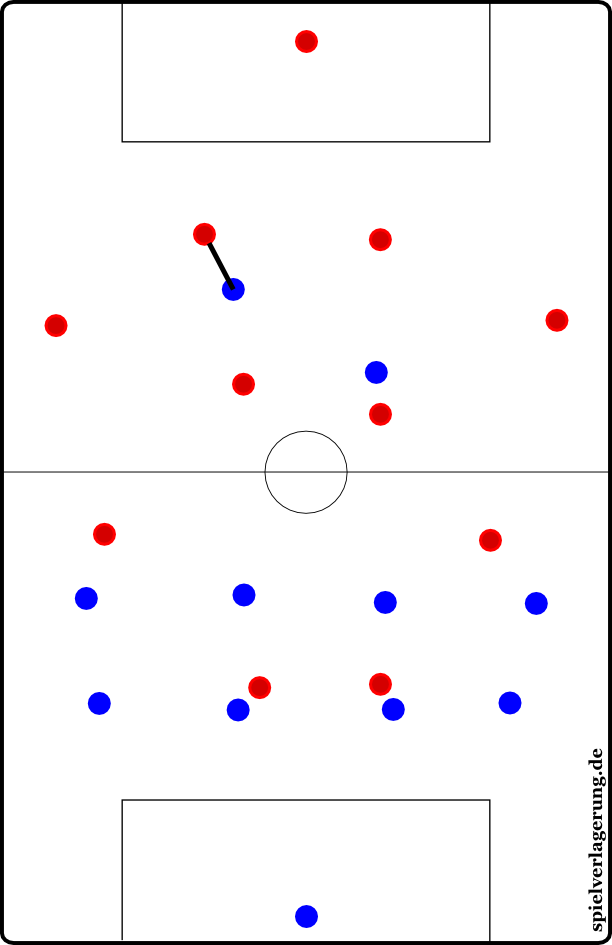

The space-oriented man coverage, where the player only marks an opponent when they enter his “man-marking zone”

This style can be practiced so that the position simply remains open, or that the hole is filled by a collective move or a replacing player. Thus, the formation remains compact, but holes may pop up in other spaces; these missing players can be especially vulnerable to quick one-twos.

One advantage is that shifting problems and space transfers don’t stand out because they are rarer and can be harder to play. The momentum of the opponent’s action can be destroyed by intelligent attacking. Their attacks can also be delayed; making them easy to figure out and interrupt.

It is a more or less difficult way of playing with many complex and intense movements. This variant makes for an interesting compromise, but probably not a permanent solution.

Variant 4: Situational Marking

The third variant is a mixture of zone and man coverage, but still belongs more to the man coverage. In situational marking, zone defense is the supreme principle. I still think it belongs to the man coverage category, because the intensity and implementation of each team are the most prominent features.

This style is best explained as a mixed variant of zonal covering and man-marking. As a case in point, SC Freiburg has their center forwards close down the passing lanes. They are both option oriented and covering space. Meanwhile, the sixes take the opposing sixes in man coverage so they can attack them instantly. This is not collective man-marking by Freiburg, but a situationally applied tactic.

Alternatively, man-marking can be briefly applied to free-running players to prevent short passing combinations in the midfield. Ideally, this will cause the opponent to play the ball backwards and the man-marker can then resume zonal coverage. Describing this as a separate variant is not enough, e.g. Rayo Vallecano against FC Barcelona or Swansea’s style. Nevertheless, this is played by these two teams, and is one of the interesting features of option-oriented zone defense. Also, Bayern have often used situational man-marking in their intelligent pressing during the second half of this season.

No team plays this way continuously. Although that would be an interesting and high-risk variant. A more flexible version of Bilbao’s style would be the nearest example.

Marking individual players

Man coverage is currently used primarily for individual players. One wants to reduce certain risks or facilitate coordination in their team so they can occasionally revive their man-marking. There are two major variants, which we will touch on briefly.

Alternative 1: Marking Key Players

The most common and frequently used way of playing man coverage is to put a Kettenhund (watch dog) on the opponent’s strategically key players. For example, marking Mats Hummels in the Bundesliga or Sami Khedira marking Andrés Iniesta in El Clasico.

The differences are obvious: teams want to stifle the creative Dortmund center-back’s deep build-up play, while the Barcelona needle player should be covered to prevent the opponent from having any extra space and stability in possession.

This option provides a simple zone covering framework with only a few players isolated from the base formation. They adopt a man coverage, but can often fall back into the basic formation. So, depending on the aggressiveness of the style, this is a way to switch between a fixed and a situational man coverage. This tactical device should survive for the next few years and is a good idea if used properly.

Option 2: Man-marking certain positions or zones

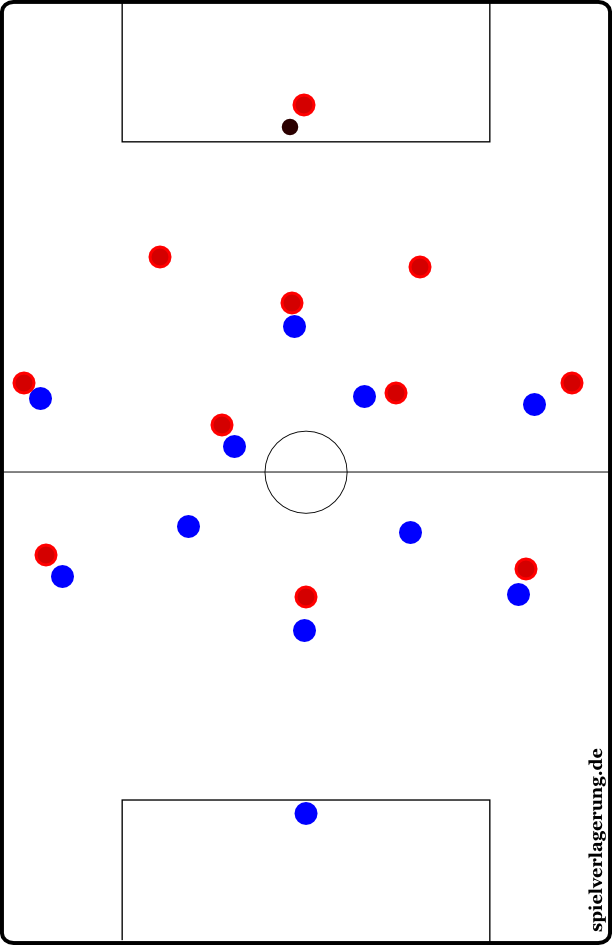

In this second option both individual players and zones can be covered. A good example would be the game against the false nine: where a central defender man-marks, then hands over to a midfielder or remains fixed in man coverage. In this case, it’s not about the individual player and his tactical skills, but his importance to the movement in the group and team tactics that should be prevented. The ever changing center-forward can then be covered, even after a flurry of attacks.

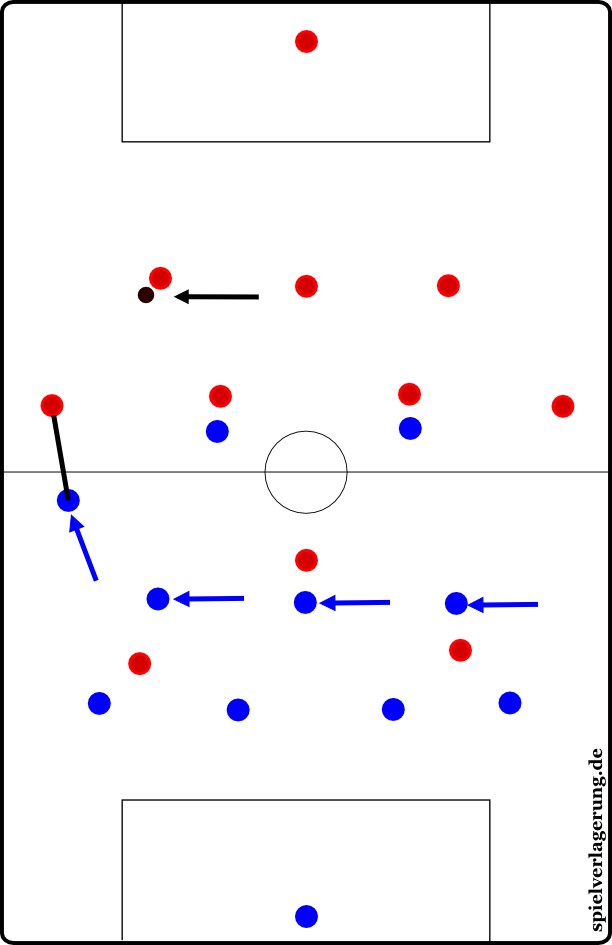

An asymmetrical shift in a 4-4-2. The left winger takes the full-back, the rest indent; this is a space-crunching and situationally-played version of marking specific positions.

full-backs and the full-backs to the wingers. This is to prevent the enemy getting a free run behind the defense or an opponent dribbling down the wing and turning their field of vision towards goal. The opponent’s build-up play is often directed back into the middle or lured into pressing traps.

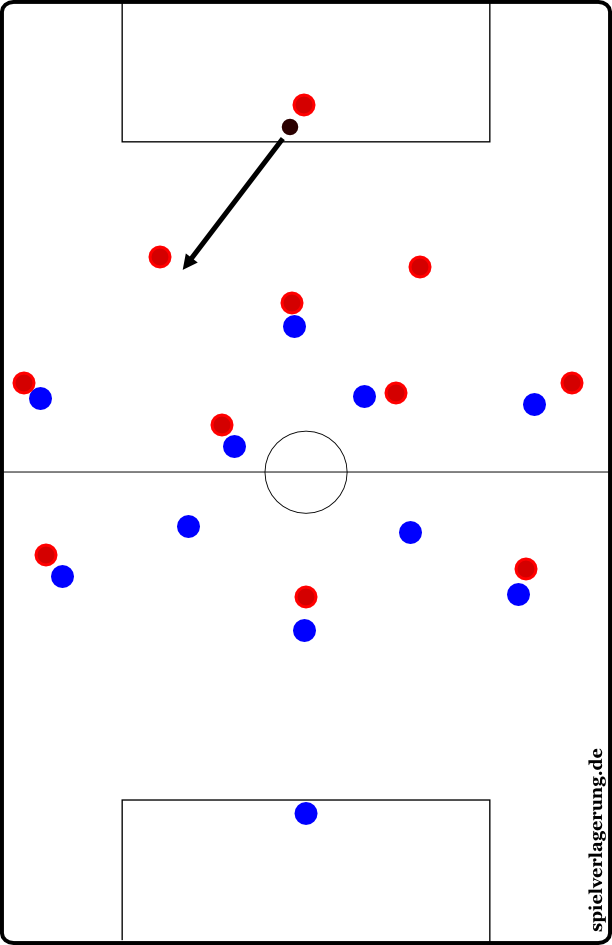

Here, Bremer set up once more in their 4-1-4-1-formation to appropriately adjust for Leverkusen’s style.

The wingers were very man oriented and settled deep, dropping if they did not have the ball. Leverkusen couldn’t make optimal use of their high and wide full-backs, but had to get stronger over the middle. –RM

What else?

In the long term, man coverage could return; but not in its old guise. The players are probably too similar athletically, the trainers must be clever, and a classic man coverage would only occasionally be successful.

But a modern variant could possibly cause a renaissance: the raumverknappende (space crunching) marking or a collectively and aggressively enforced situational marking. In the former, Arrigo Sacchi’s dogma of compactness and his four reference points are used in a man instead of a zone defense. Instead of incorporating an isolated man-marker into a zone covering formation, as is done currently, a “Raumdecker” (space marker) could be used in a man-marking team. This would help close holes and build pressing traps.

The space markers must not be fixed, but free to pull out of the mspace crunch away from the ball. The far man-marker takes over a man in an indented position, creating a domino effect and freeing many space markers. This has already been played in a separate variant with the libero as a free man and space marker.

With progressive Dynamik and game intelligence this technique – as Bayern played to some extent in the ‘70s – could provide new kinds of football tactics. Here, however there is not only the one dimension, the length of the pitch, that is scarce but the width and thus the space factor and time factor/stress. If and when the time comes, we will see (or not).

There could be further constructs and refinements to classical man-marking; for example, by double coverage as part of a compact base formation or some more bizarre ideas that we won’t go any further into in this article.

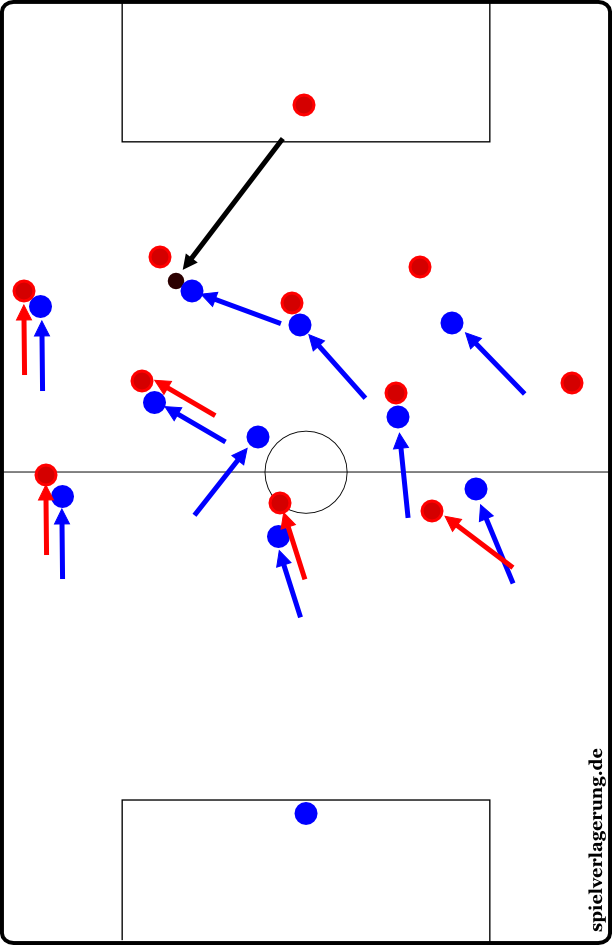

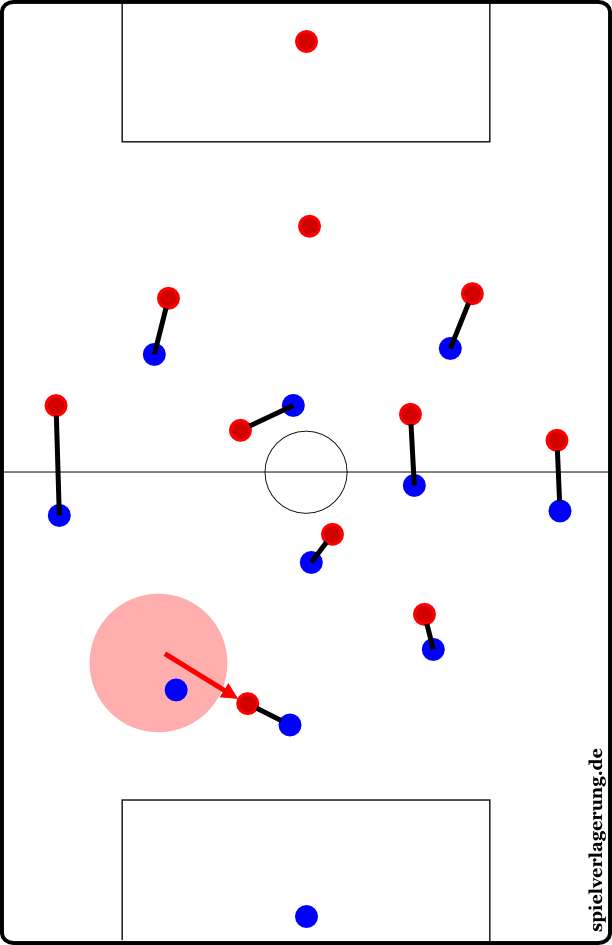

PS: By popular demand, here is my idea of space crunching marking:

The whole team goes into man coverage in order to press . Players will not be “passed” but “taken”, if you want to be precise, or even tracked. The space covering players between the full-backs take either the man (right half) or slide freely into the center (left half)

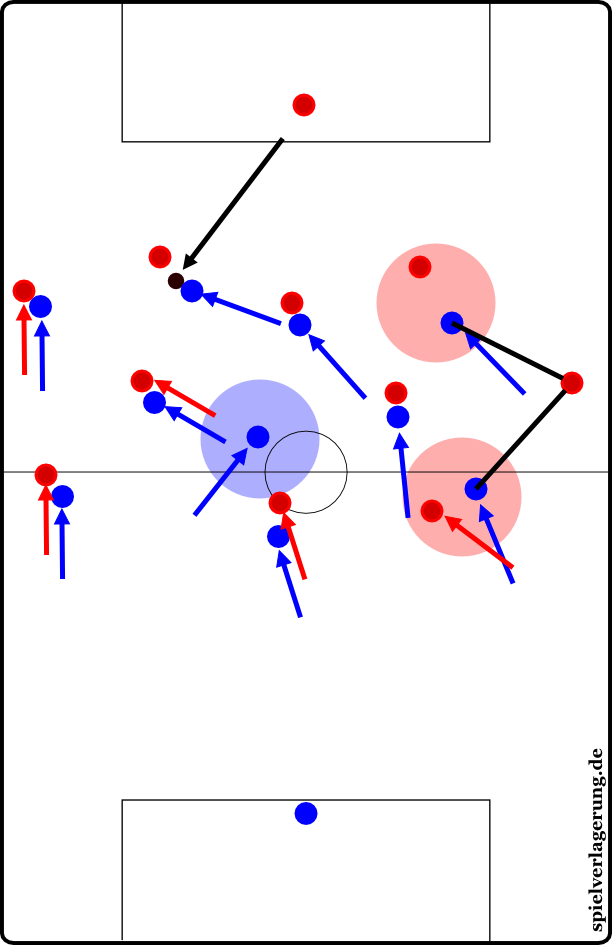

In this picture we see the new access and the “space crunch” effects in more detail.The far winger far winger broke away and goes to the center back while keeping an eye on the man behind him. The smart left winger of Team Red moves well. He is loosely followed by the right back, who holds while keeping an eye on the far wing. This is also why the left-sided six moved to the middle of the pitch.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Gwen June 26, 2016 um 5:17 am

This is one of the greatest websites i ever seen, its absolutely fantastic, if you guys can make some video clips to explain some tactical points it will be great.

vielen dunk.

albino March 18, 2015 um 5:31 pm

hey !

great stuff in this page ! really keep up this fantastic work !

Ive got one question/desire though, to ask you guys if you could make videos of man man – zonal defending , showing examples of real situations in football games, it is hard to understand it all on text.