Red Bull Salzburg under Roger Schmidt in 2014

Red Bull Salzburg are the subject of much debate. Prior to last year they were making headlines for their “history” but this season people are talking about their tactics and performance on the pitch. In recent months they have played some of the most exceptional and intriguing football in Europe. In this article we will begin by discussing the makeup of their squad before moving onto their tactical background.

The squad, the coach, and the man behind it

Some teams have put out feelers regarding the star players of Salzburg. Former Aalen player Kevin Kampl (link to two part player analysis) and the Frenchman Sadio Mane form an excellent pair of wingers who combine creativity, spectacular dribbling, defensive strength, and goalscoring. Both can be used as powerful counter-strikers as well as needle players (players who are deliberately deployed to keep the ball in tight spaces) – a very dangerous combination.

In central midfield, Stefan Ilsanker, a “(counter-) Pressing Machine” (link to a player analysis), handles the defensive duties. More often than not the experienced and technically savvy Christoph Leitgeb operates next to him; potentially as a needle player, but also as a balance, a connection maker, and link forward.

With Alan and Jonathan Soriano, Red Bull have two “complete” forwards who are capable of almost anything on the pitch; combination play, finishing, or tactically intelligent movements. The same is the case for the center-backs Hinteregger and Ramalho. Both are capable of playing as half-backs in a back three or at the 6 position in front of the defense and impress with their proactive defense, tackle rate, heading strength, and good to very good build-up play when properly involved.

Neither full-back is the absolute best in the league, though both should be included in the top tier. Schwegler in particular has made great leaps forward in the last two years in regards to his positioning and anticipation in defense. In addition, Salzburg possesses a strong bench – a rarity by the standards of the Austrian league.

They have some great talent in Valon Berisha, Valentino Lazaro, and Yordy Reyna, and a few reserve players like Robert Zulj and Marco Meilinger, who would be starters for most other teams in the league. The same also applies, to a lesser extent, to Stefan Hierlaender, Isaac Vorsah, Dusan Svento, and Franz Schiemer. Havard Nielsen, one of their great talents, recently went on loan to Eintracht Braunschweig in the Bundesliga.

But their playful and youthful quality, their carefreeness (ha, what a cliché) does not represent the whole picture. This group of talented footballers is prepared by a very competent and adequate manager.

Roger Schmidt is a no-name, but he can be proud of the success he has achieved at his previous postings. He began his managerial career in the German sixth division at Delbruecker SC before moving on to Prussia Muenster where he held his position for three years before being dismissed in 2010. Following his sacking he was hired to manage SC Paderborn for the 2011-12 season, (where he had 25 appearances as a player in the 2002-03 season) displaying tactically interesting work before joining Red Bull in 2012. In his first season at Red Bull, the club narrowly lost out to Peter Stoeger and Austria Wien’s record number of points (77 points in 36 games).

This season Schmidt has made Salzburg even stronger and they currently (ed. analysis is a few weeks old) hold first place in the Austrian League by a 27 point margin. Their pressing is more harmonious and structured, having shown no dropoff in intensity, and the counter pressing is more stable and the offense more effective and coordinated.

Sometimes their defensive play is reminiscent of the more generally structured defensive work of Rayo Vallecano, who implement a similar strategy (albeit more precisely). As for finding a comparison to their attacking strategy . . . perhaps BVB on an uncomfortable amount of stimulants?

The new acquisitions and evolution of the veteran players has taken care of the rest. Currently, they are on course for a season with 110-120 goals, on average a goal per game, and a record number of points. Following their signature win over Ajax in the Europa League they faced an FC Basel side that gave them a huge challenge with their 3-4-2-1/3-4-1-2-formation and knocked them out of the competition with a, albeit lucky, win.

In addition to this group of highly talented footballers and their highly competent manager, the sporting director is also responsible for their recent success. Ralf Rangnick, one of Germany’s pioneers of modern football, was already focused on building a team focused on pressing while at 1899 Hoffenheim and has continued that focus at Red Bull Salzburg. They consider themselves a “Pressing Machine” and even have a clock they use in training that rings if the ball has not been recovered by the defense after five seconds.

A “deep Angriffspressing” in an extremely flexible 4-4-2

In Germany, there are three categories or areas of pressing on the pitch. Imagine the pitch and divide it into three equal portions horizontally. The portion closest to your goal is the defensive zone (Abwehrpressing), the middle of the pitch is the midfield zone (Mittelfeldspressing), and the area nearest the opposing goal is the attack zone (Angriffspressing). Then you can also differentiate the three zones into two parts (higher and deeper part), also you might argue that the defending of the penalty box is also a separate aspect (Strafraumverteidigung).

Salzburg begins their pressing at the opposition’s penalty box in the deep half of the attack zone (Angriffspressing). They push high up the pitch and typically arrange themselves in a 4-4-2 formation. The two center forwards usually press the center backs and leave the goalkeeper undisturbed. In their recent Europa league match against Ajax in Amsterdam, this strategy led to Ajax goalkeeper Cillesen having the most touches of the ball. He was able to distribute the ball around the back but found no path forward.

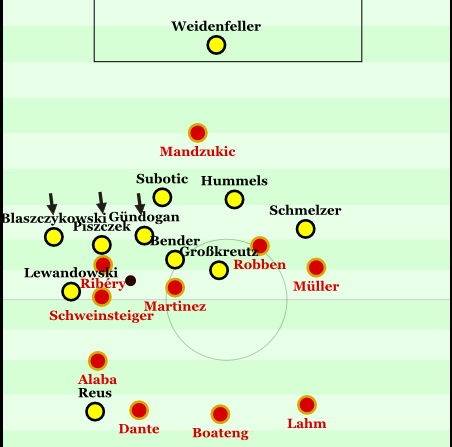

In general, attacking the goalkeeper is an ambivalent thing. Naturally it is rare for goalkeepers to be pressed as they are often sloppy in the passing game and quickly play long balls under light pressure. However, if the goalkeeper is pressed then there will be one less man in midfield. As a result, second balls are more likely to be lost and the opponent may charge the midfield zone early to try and increase their chances of winning the ball back; BVB was aware of Mandzukic applying pressure on the goalkeeper in the CL final and tried to overload the midfield again and again.

Scene from last year’s CL final 06:58; Weidenfeller attracts the pressure of Mandzukic and plays a long ball. Lewandowksi gets to the ball first, creating a battle for the second ball that Sven Bender briefly wins before losing out to Javi Martinez. FCB pressed again but Mandzukic dropped back to support the play and the beginning of play after winning the ball.

Therefore, Red Bull only presses the goalkeeper situationally or against certain opponents. Normally they leave some space on the center back who is then rushed aggressively. In some cases, even the winger nearest the ball will pressure the center back while the center forward drops back to provide a passing option in midfield.

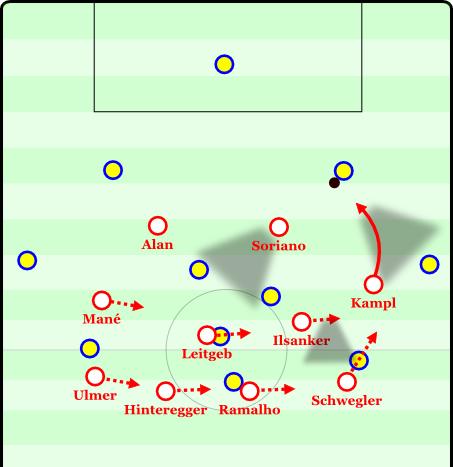

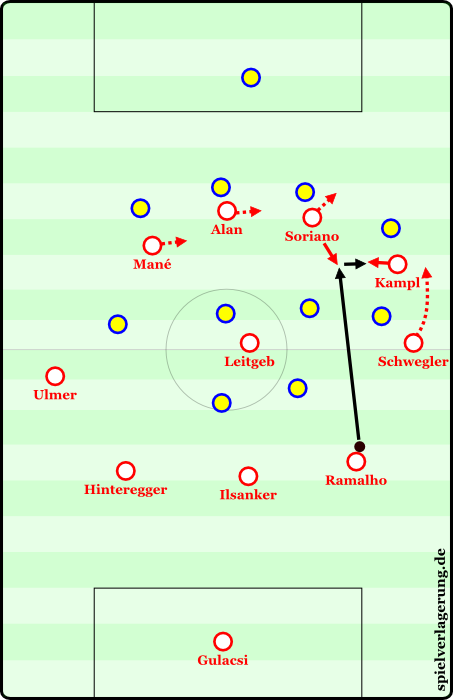

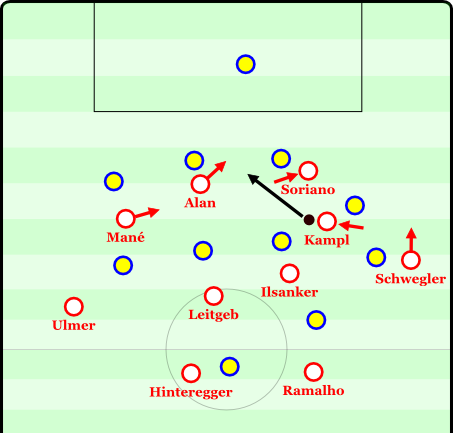

The winger moves to press the center back and arcs his run to use his cover shadow to prevent a pass to the full-back. Almost all passing options are blocked for the central defender, Red Bull has made a ball-oriented shift to the right side of the field, Schwegler has initiated a move to press the full-back if necessary.

If the opponent attempts to counter the pressing with a flat ball circulation, not only do the strikers need to push up but also the players behind them. One of the midfielders (Ilsanker or Leitgeb) will slide over to the opponent behind the two strikers, the winger (Kampl) will attack the center back, and, if possible, the full-back (Schwegler) will move up behind him to pressure the opposing full-back.

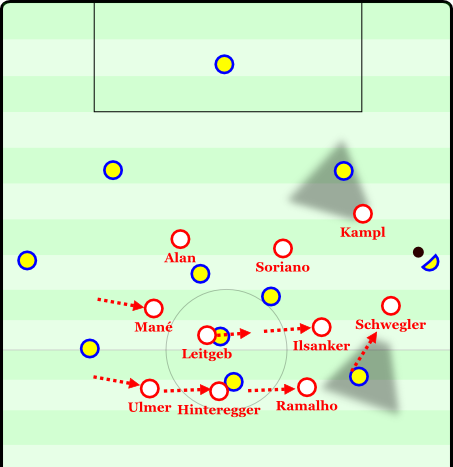

. . . and it is necessary. The opposition CB outplays Kampl and Schwegler immediately sprints forward. By the time the opponent adjusts his field of vision, Schwegler is in position to pressure him. For safety, the defense shifts right and is briefly 3 vs 3, albeit outnumbering the opposition near the ball.

Pushing higher up the pitch like this inevitably opens space for long balls down the wing, but it’s very difficult for a player to play accurate long balls in a direction outside of their field of view while under pressure. If the long ball does go down the wing, the central defender will slide over very quickly and contest the ball in the air to guard against any 3 v 3 situations at the back. The full-back then sprints back quickly to support the advanced centre-back via backwards pressing.

The central defender must not only slide out into half-space and the flanks when needed, but also into the intermediate space in the defensive midfield. If a striker allows himself to drop into this zone to receive balls, the Salzburg central defenders will man-mark the striker as they receive the pass or attempt to head the ball back up front.

This “out of position” movement by the central defenders, midfielders, wingers and full-backs brings about a certain level of instability for Salzburg. Although they try to compensate for this with flexible position changes it doesn’t always succeed. The strikers often swap sides as the game wears on and stay there for turnovers, if Kampl or Mane are unable to get back in time from their forays into the midfield, but larger spaces will still be briefly open; similar issues affect the midfield and defensive line.

If the opponent is unable to extricate themselves from the pressing and counterpressing, then the general chaos of the game will bring long balls into Salzburg’s defensive line, thus this space will definitely be played into. Fast passes backwards followed by large-scale diagonal passes and direct through balls behind the defense have been dangerous for Salzburg so far in the Austrian Bundesliga.

For this reason, it must be said that most of these attacks in the final third tend to come as a result of tough plays under pressure with too much dynamic or with bad positioning in offense and from strategically unfavorable zones. In addition, in recent months and over their winter break, Salzburg have made a big leap forward, and are significantly stronger and more stable defensively than at the beginning of the season.

Besides these issues, it should be noted that the counterattack is a possible and promising strategy against Salzburg. However, they have one of the best safeguards in the world against the counter – an outstanding counterpressing.

Counterpressing as a method of Offense and Defense

Immediately after turnovers Salzburg pull together and try to win back the ball. They use a lot of players and shift extremely aggressively to the ball in order to generate pressure quickly.

Red Bull is particularly strong after the counter; once they win the ball back, they attack again and are extremely dangerous. Their counterpressing is so strong and their subsequent attacks so effective that they often use a lost ball in their build-up play so that it falls into their counterpressing and can be quickly played forward.

This is in sharp contrast to the Guardiola approach of a flat ball circulation following a turnover. Red Bull plays long balls from their center backs into half-spaces in the middle third – the classic game of winning second balls. Once the ball has been played into these areas they usually allow the opponent to receive the ball undisturbed and then press him immediately. After winning the ball they move towards goal with quick combinations and shifts into the second half-space.

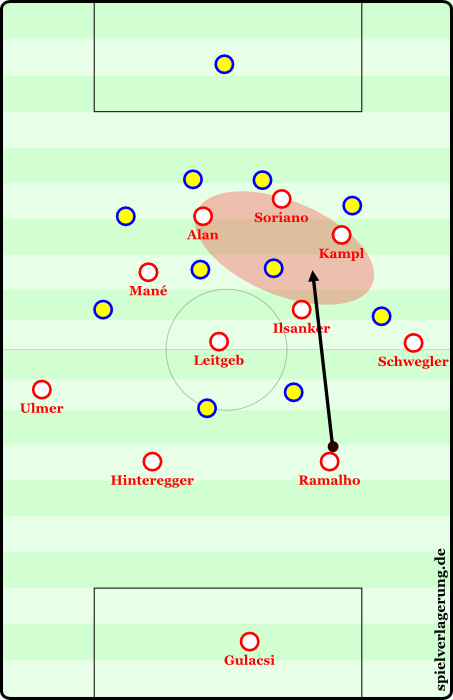

A long ball forward from Ramalho where Red Bull attempts to win the second ball. Often they allow the opponent, in this case the 6, to briefly stop the ball so that they can press him, win the ball, and look to move it forward as quickly as possible. After these battles they can create a 4v4 locally and generate a lot of momentum in their movements.

By doing this, Salzburg is able to bypass the first third and the front line of the opponent’s pressing and quickly gain a lot of space. In addition, they gain simple entry into the opponent’s formation, which isn’t easy to do in build-up play due to the staggering of the 4-4-2. Against compact or high pressing they use this strategy to get behind the defense with the outstanding pace of Mane and Kampl.

But they don’t just use long balls in their buildup. Time and again they employ a more patient passing game, keeping the ball on the ground. Sometimes their formation morphs into a 3-3-4 with one of the midfielders (Leitgeb or Ilsanker) rocking out while the other acts as a safeguard and ball-hunter in the middle third (Ilsanker), or a intelligent playmaker and situational needle player (Leitgeb).

However, due to the speed of passes here they often see their attacking approach stifled by the whistle and potential turnovers. These passes are often extremely risky, moving so fast that they can be difficult to direct into the opposition midfield or even get behind. Then again this is the effect of quick attacks. Although they naturally have the occasional long ball circulation, they usually rely on fast horizontal passes, with a lot of movement from the wingers and center forwards dribbling and looking for passes into the channels.

A very long ground pass from the back, which bypasses the front six of the opposition (so that it can’t be intercepted these passes are usually played with extreme pace). Bayern uses the same type of “laser pass” from Boateng. If the ball arrives up front, Soriano can – thanks to the enormous pace – simply let it bounce. Kampl indents, dribbles, and pushes into the open space between the lines.

The wingers play a supporting role in all of the attack schemes. Not only in the quick counterattacks after contested balls, where there ability to resist pressing and play in the narrow spaces of the opponent is important, but also for their pressing. They skillfully combine this with their defensive duties and it is one of the most spectacular aspects of the Bulls from a tactical perspective.

The polyvalent role of the indented winger

As soon as the opponent is able to escape their high press or if for some reason they are not pressing them high for a tactical reason, Red Bull retreat into an extremely compact 4-4-2. The two strikers position themselves between the opposition’s defensive line and midfield, looking to block back passes. But what’s particularly interesting is the extreme horizontal compactness of their formation.

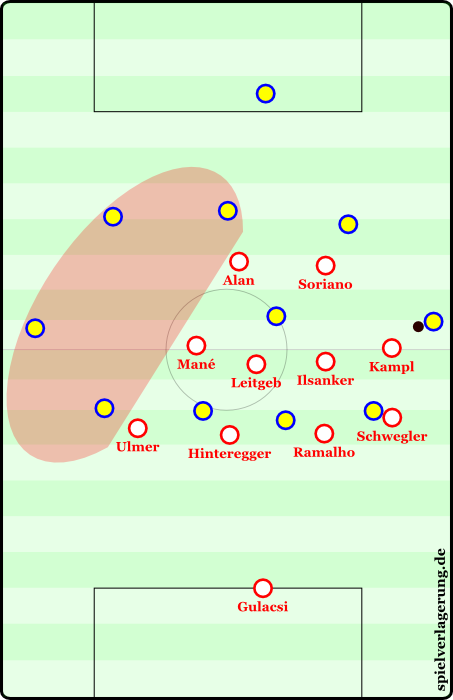

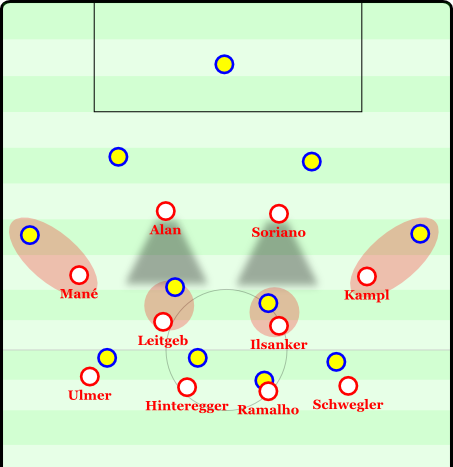

The winger furthest from the ball will indent, or move in very far centrally, operating in wing attacks from the middle of the field or even closer to the ball. In this sense he is ball oriented and working to reduce space between himself and the ball by moving extremely far from his wing. On throw-ins, the winger is even closer to the opposite flank than the center of the pitch. On paper it seems like Red Bull is vulnerable to switching flanks and that there are no positive effects resulting from the winger indenting.

Red Bull’s extreme horizontal compactness is easy to see here, particularly in the positioning of Mane. Mane in particular pushes even further away from his flank, often closer to the other wing than his own, crossing an imaginary vertical center line. On throw-ins, Red Bull squeezes into a 25 meter radius from the touchline. Four opponent players have been effectively isolated and removed from the game for a brief period.

But the opposite is true. If the opponent plays direct passes into the midfield, the sixes (Ilsanker and Leitgeb) can act more freely, as Mane and Kampl are there to support them. The sixes back each other up, the near-six (to the ball) is helped out by the near-winger and the far-six is supported by the indented far-winger. This helps both offensively and defensively.

After contested balls, the wingers are already in the vicinity of the center or half-space. This makes them available to receive short simple passes to escape pressure from the opponents’ pressing and increases the speed of transition into the counter attack, giving the wingers good strategic positions with a lot of good options.

On the wings they could easily be pushed away, but in an indented position they can immediately target open spaces and have many passing options in close proximity. Because of the fanned formation of the opponent they can even directly overload space, pulling and forcing the opposition full-back into a quick sprint centrally towards his own goal, thereby opening space for the Salzburg full-back to move up and provide width.

Theoretically, an opponent can get around this by quickly switching play. However, to pull this off the pass must be extremely strong due to the pace of Kampl and Mane. On long balls to either side they are capable of quickly sprinting to the ball and applying immediate pressure and due to the difficulty of producing an accurate long ball it is often more likely that the opponent will lose the ball than produce an effective attack into the (supposedly) open space on the wing.

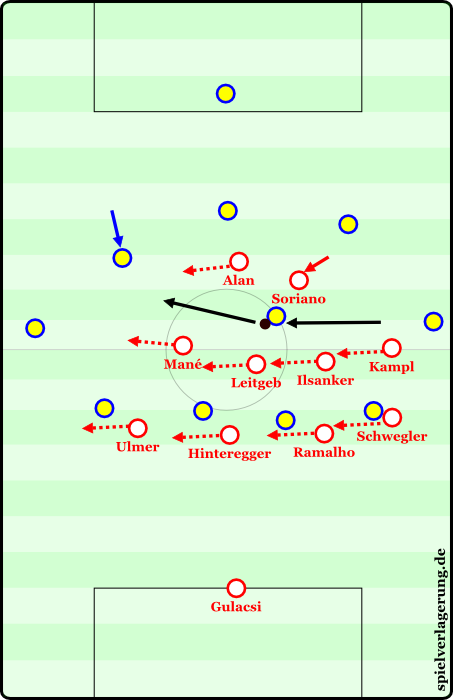

With two very quick and precise the opponent switches play. The midfield shifts to one side, Alan begins pressing, after Soriano had a brief spell of pressure. The goal is to return the to the basic defensive formation before the opponent has the ball under control on the wing.

If the opponent switches play via short or quick passes rather than long balls, then Kampl and Mane move intelligently.

With every pass they calmly move back towards their original position and focus on preventing diagonal balls and vertical passes from being played forward. Instead, they look to push passes to the side of the pitch, where they can be more effective with their pressing by using the sideline as a defender. By channeling passes this way they ensure that neither short, switched passes nor long switched balls come to fruition.

Instead shifting the sides with two medium length passes, which come back diagonally into the middle and play into the movement, might be able to neutralize the movement of the indented wingers or even exploit it.

But situationally, the winger will push from his indented position and blitz forward, instead of continuing his lateral movement, pressing either the opponent 6 or 8, while the 6 of Salzburg moves into the resulting hole. If the ball still arrives on the now open side (although this can be prevented by the arc-like runs of the wingers), then the full-back leaves his position to press and the remaining back three protect the space behind him from the opposition, ensuring equal numbers.

But sometimes mistakes arise from passes into tight spaces and poor first touch. Here, Leitgeb, coughs up the ball, the opponent takes the ball and tries to adjust his field of view, however, thanks to his indented position, Mane is able to move up and win the ball. With Soriano and Alan so close, he automatically has passing options that can run free and begin a counter attack.

The winger doesn’t just move over for defensive reasons. His offensive pushes into the midfield and half-spaces also fix one of the core problems of the 4-4-2, which Salzburg interpret very fluidly.

The special strength of the flexible 4-4-2

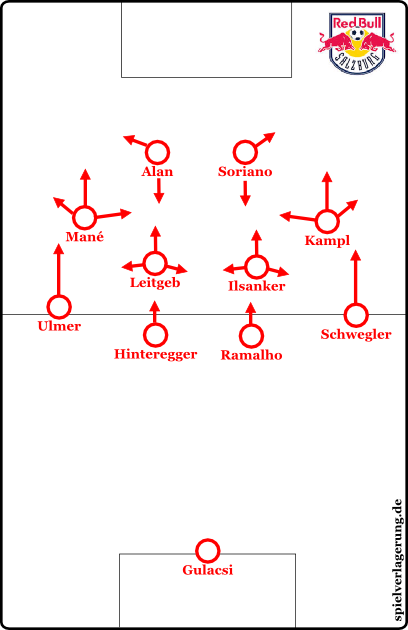

The offense’s biggest problem in the 4-4-2 is the space around the (non-existing) ten and the lack of connection between the midfield and attack in the midfield zones and the staggering of players in the final third and strategically important areas. Red Bull have several different and varied approaches to this problem.

The most striking and oft-used strategy, of course, is the indented and free winger. They act as masked tens again and again in their role in central midfield and half-space in order to provide passing options. Kampl (and Mane to an extent) even drop into midfield to receive the ball and create from deep.

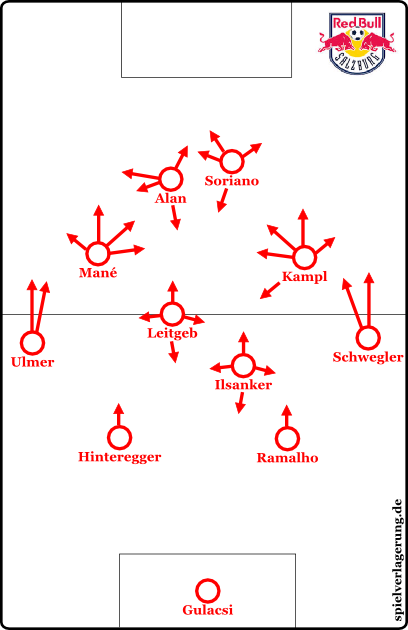

Normally, they overload the half-spaces and look for possible combinations in the space between the lines. They often find space for themselves behind the opposition midfield to receive passes into the channels, attempting to spin, head towards goal, and with their dribbling threat provide possible combinations and overloads. In addition, they both move so that they can combine with each other and so the two full-backs can provide width.

The center forwards support these movements. In the first phase of attacks they bind the center-back and provide two passing routes forward, allowing them to hold up play for the runs of the wingers. In addition they move very flexibly and with great intelligence.

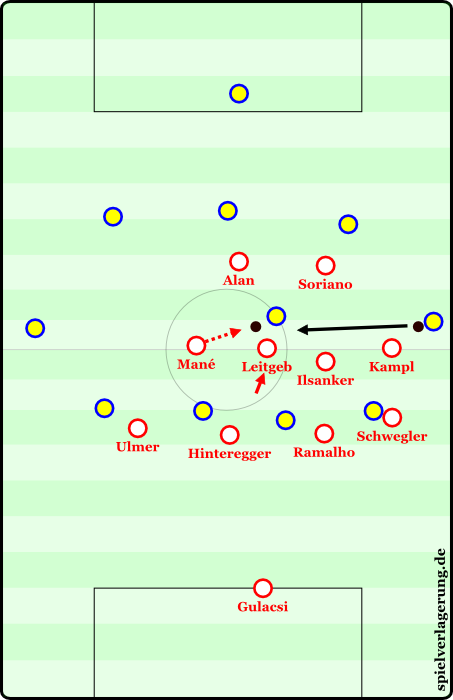

Therefore, Soriano and Alan repeatedly move to the side of the pitch when the wingers indent. This binds the central defenders so they can’t move out early, using elusive movements to open the channel between the center backs, or binding the full-backs when they try to man-mark Kampl or Mane.

These evasive movements are occasionally used in different ways wider of the box and are not only elusive but serve as possible combinations; the winger can move vertically into the space vacated by an evading striker (usually behind the opposition 6), who occupies the attention of the other center-back and runs to the near post, while the other winger occupies the back post.

The varied movements of both strikers and the flexible occupation of the center by elusive runs is due to the forward presence, the momentum and speed of the lone player and the elevated tactical crispness of the group. The middle of the pitch also serves as a linkup area for diagonal passes into half-space when Leitgeb or Ilsanker play forward and the winger indents in order to receive the next pass.

Here we see the indentation of the winger, the evasion of the center forward, and the pushing up of the full-backs. As Kampl pushes inside, the opposition full-back follows him. In front of Kampl, Soriano drags the center-back wide and opens the channel for Alan as he offers himself as a diagonal option into space, where he will have Schwegler supporting him. Even Mane indents and offers himself as a combination partner, Soriano has the best field of vision of everyone and can make a goal-oriented move again.

All in all, three or four players occupy the space of the ten in this nominal 4-4-2. Both wingers, a striker, and one of the six take care of this. But the occupation of the space around the ten is particularly crucial, especially the strong capture of the half-spaces. Which are some of the most important strategic areas as I will show in an upcoming article. Thus, this 4-4-2 is more of a 4-2-2-2 in a 4-2-4 role distribution, which rather reflects the offensive component of the Salzburg style.

Special adaptations possible

Personnel changes for rotation are usually handled by Schmidt with a tactical focus. Therefore, Schmidt adjusts his roster for the upcoming opponent and also uses formations other than the 4-4-2/4-2-2-2/4-2-4 in certain games and stages throughout the season. In some games, for example, he played a 4-1-4-1/ 4-3-3, while in others it was a 4-2-3-1 with Valon Berisha coming into the team and playing as the ten, occasionally even a 4-3-2-1 was used.

Sometimes the height of the pressing and the attacking style has been changed. A specific example of minor adjustments within the formation framework is the game against Austria Wien. Austrian star-striker Phillip Hosiner was man-marked before any potential turnovers in play. Ramalho or Hinteregger, for example, man-marked Hosiner before the execution of their own corners. Clearances or passes to him went into the void and Austria’s only relief option was nullified by their movements and rarely came into play. Even these small, player-specific adjustments show the class of Roger Schmidt (Link to three-part analysis of this game).

Another perhaps underestimated aspect of their success is their training work, because their efforts stir up quite a bit of controversy.

Doping allegations; the resting and the false pressing

The intensity of their play has generated critical comments and implicit references to possibly unfair practices in the training of the Red Bulls. It’s obviously impossible for a tactics analyst to say whether or not this is true. What I can say, however, is how the pressing looks and whether there are other possible explanations for their ability to press so effectively.

It is extremely difficult for them to constantly maintain the intensity of their press over long periods. In the final minutes of some games, Mane and Kampl have difficulty meeting the tactical tasks given to them and look tired, while in other games they are able to keep it up for 90 minutes, which puts into perspective the psychological component of the tactic.

The most striking aspect of the game against Ajax was the rest in their pressing. In that game they were able to stop pressing without actually stopping their pressure. Sounds like a paradox, right? It is. It works by only leaving certain passing options open, but still maintaining a very high block and staying close to the opposition so that they can begin pressing at any time. The opponent is allowed breathing room, i.e. space and time to circulate the ball, but can do no damage.

The psychological component behind this is that Red Bull has pressed so successfully and with such intensity that the opponent will attempt neither risky combinations nor supposedly easy forward passes. In these phases, the opponent of Salzburg seems to be mentally exhausted while the Bulls are physically so.

Against Ajax it was so apparent because Ajax wasn’t attempting to play on the shape of the Bulls. While other opponents hit long balls and at least tried to attack, Ajax was the perfect opponent for this “resting pressing.” The Dutch circulated the ball around the back, taking advantage of the two to three passing options that Salzburg left open and then deliberately played the ball back to the goalkeeper. Because of this, Red Bull had short resting time in the enemy penalty box where they could just move their compact block with less intensity and build up strength for a new surprise attack of pressing.

The resting press. Red Bull leaves the center-backs open, the strikers must block the opposition midfielders with their cover shadows, while Leitgeb and Ilsanker man-mark. The wingers leave the full-backs open short-term, so the goalkeeper won’t immediately kick to them, when they were unmarked. In a normal press they would either push up and put pressure on the center-backs or leave the full-backs open to provoke passes to them and then press.

The second aspect goes hand in hand with this. It is the “false pressing,” which we have already described a few times on this site, which came from Valeriy Lobanovskiy. False pressing means that a team doesn’t press intensely as a collective, only individual players press. The opponent, simply because of previous intense pressing, panics early and loses the ball. This tactic also means that the Bulls sometimes create more pressure than their effort would suggest.

Whether or not the rumors are true is impossible to say. In the end this wasn’t actually matter for analysis but it provided a nice way to integrate the two specific aspects of their pressing.

Conclusion: Dynamic football and an outlook for the future

The current excitement around Red Bull – never before have I received so many requests for a team analysis – which was surprising for many, seems entirely justified to me based on their recent advancement past Ajax in the Europa League. They have almost perfectly embodied the projected ideals of their sporting director; if they can keep their form for the second half of the season they could potentially become one of the best five teams in the German-speaking countries.

They are particularly impressive because of the extreme dynamism they bring into their game. They play lots of quick and risky passes, their combinations thrive off Ablagen (direct short passes with one touch after hard passes), short passing combos, and passes into the channels. Due to the partly improvised decision making in the final third with keeping players compact and close to one another, and their attempts at playing in confined spaces with dynamic needle players like Kampl and Mane, they produce remarkable rhythm changes in their passing game, which lead to spectacular attacks.

This combination of speed and risk-taking in the passing game (only Kampl is near the key players in the Europa league with his 80% pass completion rate) combined with their high pressing and great counterpressing, leads them to be considered current favorites for the Europa League (ed. *Salzburg recently lost to FC Basel and were eliminated from the competition). Their playstyle, in terms of attractiveness, group tactic implementation, strategy, and individual strength, is rated very highly.

They combine this style of counter attack with their possession game, where they keep trying to break the opposition defense with momentum and quick attacks. No team in Europe can currently match their level of intensity.

In the medium-term future, they could become Champions League quarter finalists and stand a chance of progressing past certain opponents.

But this is, of course, no absolute statement; against teams with a lot of dynamics (a la an individually stronger Hoffenheim) or the individually strong “Bolzern” (who, as one of our readers, Woody10, brought to our attention, they eliminated from Champions League qualification in person of Fenerbahce) or even against teams that can handle the short-term instabilities that arise from intense pressing, like Bayern or Real Madrid, they would stand no chance without further improvement, despite surprisingly beating Bayern in a recent friendly (link to three-part analysis of that game).

Overall, we can say that if this team stays together and continues to play with this intensity, it would be well within the realm of possibility for them to get through the Champions League group stage and possibly provide a little surprise. To this end, in view of the squad policy since the arrival of Rangnick and Schmidt, it is expected that the team will improve. They have already completed the signing of Peter Ankersen, the polyvalent young full-back, from Danish side Esbjerg fB.

Furthermore, in addition to future talents like Braunschweig’s Havard Nielsen, his compatriot Valon Berisha, 18 year old rising talent Valentino Lazaro, Yordy Reyna, and a focused youth effort, they have added individual talents to their farm team FC Liefering, where they can successfully park Andre Ramalho. Long term they will likely be a force to reckon with in Austria. The Red Bull Salzburg Project – despite major criticism of the club – is truly exciting from a tactical perspective.

3 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Kai Werring June 4, 2015 um 10:02 pm

Absolutely outstanding in depth analysis. I wish you had dozens of in depth looks at teams in a book, I would purchase that immediately. & although its farfetched, a magazine of these analysis — players on the rise — and new tactics for the future would be insane!

Thanks for all that you do. It’s groundbreaking.

Alex March 13, 2015 um 8:27 pm

So many months after this piece was put up, I still come back and read it from top to bottom. The analysis is simply priceless.

Vinny April 29, 2014 um 1:18 am

man what an amazing tactical analysis great, learned so, so much tanx