Team Analysis: Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool

The final day of the 2014-15 season saw Brendan Rodgers’ Liverpool side get thrashed 6-1 by a mediocre Stoke team. After challenging for the title in the previous season, the transfer of Luis Suarez and poor health of Daniel Sturridge created big issues and performance dropped off a cliff. Whilst Rodgers was previously able to rely on his talented personnel, he struggled to implement a consistent strategy from this point onwards. He was granted the start of the 2015-16 season to rectify the issues, but was unable to do so. He was sacked after a 1-1 draw with Everton in October. A few days later, Jurgen Klopp was hired.

Klopp has already made a number of changes to the systems utilised under Rodgers, and Liverpool have shown many promising signs despite clear tactical and personnel issues.

Pressing and counterpressing

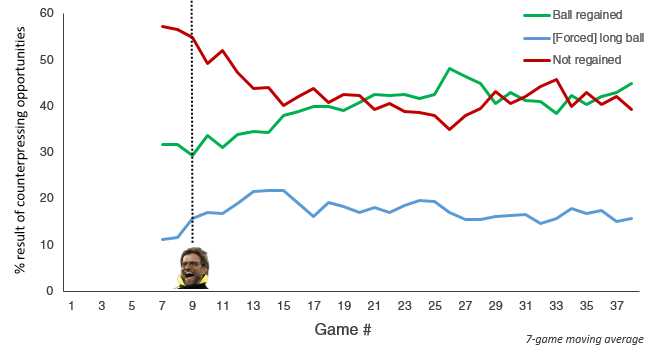

One major tool used by Jurgen Klopp is the infamous counterpress: attempting to regain possession immediately after losing it. Whilst Rodgers’ Liverpool were a high pressing team at their peak in 2013-14, this often came in established possession rather than actively focusing on recovering the ball immediately. But during 2014-15, the team even began to lose their focus on pressing itself as Rodgers found himself stuck between philosophies.

Whilst the nuances of counterpressing can take many months to fully implement, Klopp was able to make immediate improvements.

On Jurgen Klopp’s debut (game 9 of the season), Liverpool visited another team focused heavily on counterpressing, Mauricio Pochettino’s Tottenham. With less than a week of training, Klopp was already able to instill a few key principles of counterpressing into the team. Despite this, many of the suitable support structures were not in place to implement a successful post-counterpress transition (after only days of coaching, this is to be expected). This created a match with many individual duels and second balls, but little sustained possession or clean combination play.

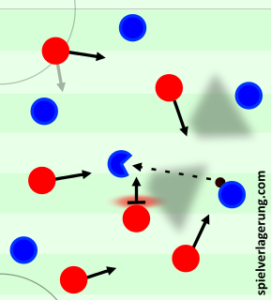

The general aggression of the counterpress was vastly increased, but more importantly, the triggers for counterpressing were seemingly more clearly defined than under Rodgers. The main signal for triggering an ultra-aggressive counterpress was the opponent receiving the ball with his back to [Liverpool’s] goal. This is the most common trigger in general, because makes it more difficult for the receiving ball-player to view or access the game behind him. It reduces his passing options and makes it easier for the ball to be regained. If the ball is not won back quickly, then it forces the opponent into a backwards pass and gives the team additional time to re-structure.

Another core principle the players exhibited almost immediately was a more intense press in the wing area. This is simply because of the lack of connectivity to the other areas of the pitch.

![Fewer areas of the pitch are immediately accessible from the wing ([LINK]from TP’s Empoli team analysis[/LINK])](http://com.spielverlagerung.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/07/Connectivity-of-the-wing.png)

Fewer areas of the pitch are immediately accessible from the wing (from TP’s Empoli team analysis)

https://twitter.com/edAfootball/status/742793234452217856

Klopp was quickly able to improve on these base rules. More complex principles were introduced, and the counterpress peaked around the turn of the year, despite an injury crisis. Perhaps the success would have been improved even further if the team did not (rightly or wrongly) prioritise their Europa League campaign over the Premier League.

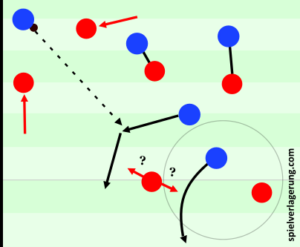

An example of a common early pressing trap: allowing the ball to return to the halfspace after it previously reached the wing.

Around this time, the team began to introduce pressing and counterpressing traps based on the key taught principles. The most commonly used trap was to force the opposition into a wider area, and allow a single open passing lane into the halfspace. Based on the position of the ball, this player was forced to have an outwards-facing field of vision, and would be pressed heavily from all directions upon receiving the ball. Backwards pressing from the ball-side attacking midfielder played a key role in ensuring the opposition could not merely recycle possession.

The specifics of the trap itself varied depending on the system used and opposition faced. For example, a less aggressive version of the same press may be to force a ball backwards to a central defender. If co-ordinated previously, this allows the central midfielder to aggressively press the opposition receiver. With sufficiently altered movement to close potential passing lanes, this can force a long ball forward.

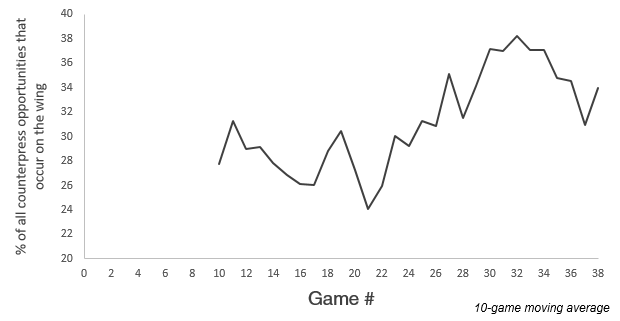

But the other key reason that Liverpool’s counterpress improved during the season was the preparation for the counterpress during the possession phase. As the year went on, many more of Liverpool’s attacks were forced to the wing.

Percentage of all potential counterpress opportunities in the opposition half that occurred on the wing

Whilst this can have disadvantages in attacking, it creates more stability if the ball is lost. With a strong central presence, it becomes much easier to defend transitions that start from the wing because of the reduced passing options the opposition immediately has.

This increase was largely due to two connected reasons. Firstly, the emphasis of Liverpool’s attacks has gradually moved wider: in the first half of the Premier League season, no team completed a lower percentage of their opposition half passes on the wing. This improved to 13th in the league for the second half of the season.

In facilitating this focus on wider possession, the team’s structure improved and began to focus more on utilising the halfspace as a means to attack rather than the centre itself. This was particularly the case in Klopp’s 4-3-2-1 shape, where both the attacking midfielders and outside central midfielders would spend much of their time in the halfspace (with license to drift wide depending on the movements and positioning of their teammates).

This increased focus on the halfspace had a big effect on attacking midfielders Firmino & Lallana, but neither were the very best contributor…

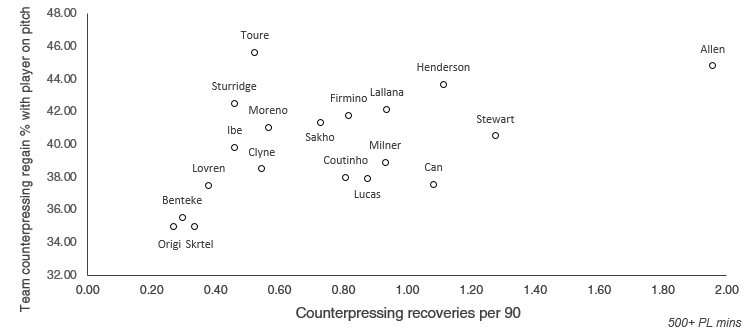

Individual counterpressing contributions, and effect on the team’s ability to regain possession quickly

Initially brought in as the ‘Welsh Xavi’, Allen has found himself without a defined role at post-Rodgers Liverpool. Injury troubles have contributed to a lack of consistent starts, but even when fit Allen has struggled to start games regularly. There are questions about his physicality (or lack thereof) and how this can be a detriment in Klopp’s system, where second ball duels in tight spaces form a key part of a midfielder’s role.

Despite this, his contributions to the counterpress when he does feature are unparalleled. In general pressing phases, his contribution to regaining possession is more indirect: closing passing lanes and adjusting to his teammates’ movements with intelligent decision making. Within the counterpress, his ability to regain the ball himself is magnified due to his impressive in-possession positioning. Particularly when the ball reaches the final third, it is rare that Allen is more than one pass away. This allows him to easily shift towards the opposition, or aggressively close the ball-player if the situation demands.

As the outer central midfielder in the 4-3-2-1, he was given license to make extreme vertical movements forward. In advanced positions, he provides good value in stabilising possession with good decision-making. If a quick combination play is available, then he facilitates this with quick feet, but also understands when the tempo needs to be reduced. This general game intelligence is perhaps one of the reasons he makes such an impact as a sub, and why his GoalImpact score is one of the highest in the Liverpool squad (2nd only to Jordan Henderson).

Increasing horizontal compactness and ball-orientation

Improved ball-oriented shifting was one of the key features that Klopp was able to implement into Liverpool’s press almost immediately. During Liverpool’s peak under Brendan Rodgers, there was often an aggressive initial press without suitable compactness and ball-orientation. This means if the opposition break the initial press with quick feet or a sharp pass, there is an immediate transition opportunity.

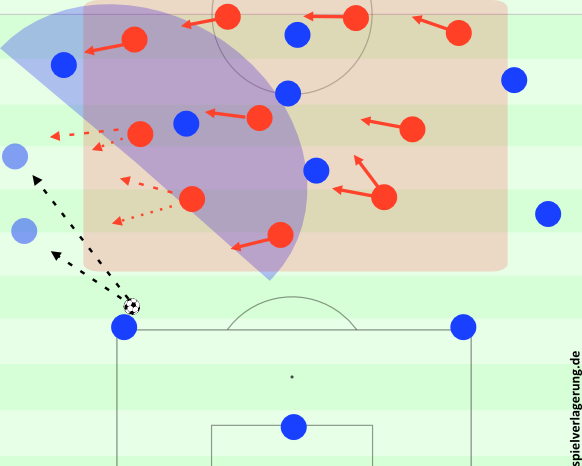

When the ball is in the centre, Klopp’s team will often disregard the wing and focus almost entirely on defending the halfspaces and centre. Whilst the centre is occupied, the team’s forward is tasked with closing inside passing lanes and forcing the opposition towards the unoccupied wings. The most common example comes when one opposition central defender has the ball – Liverpool’s forward disallows the pass to the other central defender whilst his teammates occupy the centre.

This was one of the primary strengths of the 4-3-2-1 shape that Klopp used many times throughout the season. Once the pass has been forced to the opposition full-back, Liverpool’s outside central midfielder can aggressively press whilst closing the inside passing lane. The ball-side attacking midfielder can then curve his movement to ensure the opposition cannot recycle possession through their central defenders.

Liverpool’s pressing shape in their 4-3-2-1, from RM’s analysis of Klopp’s Liverpool debut

The players developed more intelligence in adapting their pressing movements as the season developed. The win against eventual Premier League winners Leicester was particularly impressive due to Liverpool’s dominance of the transition phase (one of Leicester’s key strengths).

Because of the compactness of the two teams, much of Leicester’s transitions came from trying to stretch the pitch into the previously vacant wide areas. This limited the influence of Leicester’s central midfielders, and consistently forced build-up through the full-backs. If the ball was quickly regained, then the team could attempt a transition. For the opposition to stay suitably structured in the chaos of this transition moment requires huge levels of co-ordination. In many instances, it will create some large spaces (and many smaller spaces) that Liverpool can immediately exploit with quick vertical passing and sharp combination play.

https://twitter.com/edAfootball/status/752104074028445696

The role of the attacking midfielders (generally Lallana & Firmino in the 4-3-2-1) in these instances was particularly interesting. Many times, when Liverpool’s forward forced the ball wide, they would remain in an advanced position, ready to press the opposition ball-side central midfielder should the ball return into the centre of the pitch. This adds another dimension to the press that was sometimes vacant when the team pressed in a 4-2-3-1 shape.

Backwards pressing

The nature of their positioning generally meant that these players were pressing backwards, often outside the opponent’s immediate field of vision. Lallana in particular benefited most from an extended shift to the 4-3-2-1 during game 21 of the season. This improvement, and their role in particular, mainly came in the form of picking the pocket of the opponent with a tackle from behind. Firmino & Lallana had the highest percentage of their counterpressing recoveries come as tackles of all Liverpool players.

Aside from the player curving his movement to stay ‘out of view’ of the ball-player, these tackles often necessitate slightly different body positioning to an ordinary tackle. With the ball on the other side of the opponent, there is more need for use of the upper body to disrupt the balance of the opponent. This slight push can create a split-second of disorientation for the ball-player, particularly if he was unaware of the approaching presser.

Additionally, sometimes a small ‘hop’ immediately prior to making the tackle can give the tackler an advantage when tackling from behind. This small jump has the added benefit of avoid the shield that some players naturally use to protect the ball. When the opponent’s leg is extended, it clearly has to be at an angle because of the biomechanics of the hip joint. Making a slight hop over the leg (if it is extended in a shielding motion) allows less diversion of tackler’s movement, making it easier to reach the ball quickly.

Another vital advantage of this downwards force (after the peak of the natural trajectory of a jump) is that it creates enough force for a tackle and pass to be made in one motion. Instead of making an additional movement with his leg, the player can use the force generated from the jump to deflect the ball to a teammate.

For obvious reasons, this quickens the process and reduces the likelihood the tackler will immediately lose the ball again. When there is a suitable support structure around the ball, this can create dangerous transitions through the use of combination play and third man runs. Within the 4-3-2-1, the two attacking midfielders would ball-orient in an attempt to overload the nearby zone. When this is the case, the ‘third man’ can anticipate the regain of possession. This creates the opportunity for the player to ensure he is open for a pass from the recipient of the tackle-pass, allowing the ball to be quickly moved away.

https://twitter.com/edAfootball/status/752119227327344644

Firmino & Lallana were the primary proponents of such techniques. Coutinho had more difficulty achieving this; despite curving his movement suitably, his tackling positioning was often poor. This makes the Liverpool press more one-dimensional, and is perhaps one key reason why the team were much less effective at regaining the ball with Coutinho on the pitch, despite the fact he had a similar number of direct regains from counterpressing (0.81 per 90 minutes) to Firmino (0.82) and Lallana (0.94).

Defensive transition issues

Focusing on counterpressing rather than dropping deep to regain structure is an inherently aggressive tactic. Klopp’s system is focused more on quickly closing the space around the ball with large numbers of players converging from all directions. The upside, as mentioned previously, is that this can allow the team to quickly regain possession and even start its own attacks.

The downside is that an aggressive counterpress from deep in midfield can allow the opposition more opportunity to transition if the initial press is beaten. This effect is magnified if the team prepares poorly for the counterpress when in-possession, and does not have good pressing access from all sides of the ball to immediately flood the new opposition ball-player.

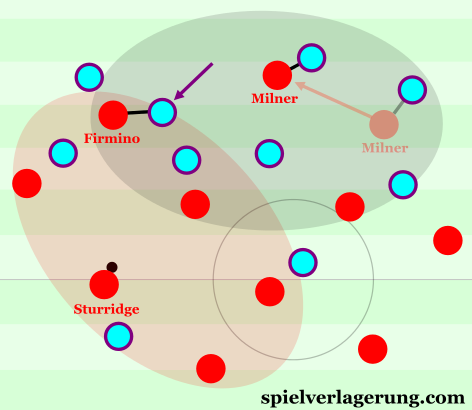

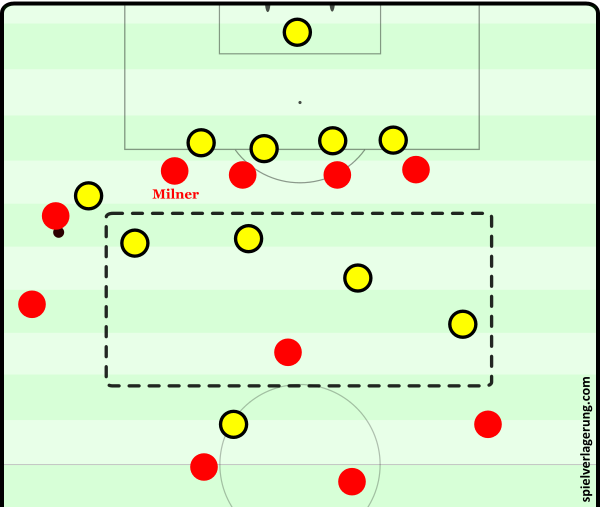

Liverpool suffered from this very effect in the latter stages of the season, particularly when James Milner was utilised in a double pivot with Emre Can. Despite joining Liverpool largely to play in central midfield, Milner spent much of his time situated anywhere but central midfield in these moments.

Not only does this poor structure make it more difficult to attack effectively, but it makes quickly regaining possession a near-impossible task. With such poor pressing access, Dortmund can easily escape.

Milner also exhibited one of the other key negative traits that caused issues for Liverpool midfielders: an over-reliance on situational man-marking. Despite largely using a zonal-based system, occasionally the central midfielders would push forward and aggressively pursue potential passing options. Because of their backwards-facing field of vision and tight pressure from behind, this makes a pass into those players less likely. But it also leaves a large open space behind.

This was exploited by the opposition on a number of occasions during the season, but chiefly by Dortmund and Henrikh Mkhitaryan. A 2v2 man-marking of the midfielders can leave space for the opposition #10 to drop into the space behind Liverpool’s midfield and receive the ball. This was particularly effective when the opposition were attempting to build from wide, and the full-back could play a diagonal ball into the halfspace behind Milner & Can. The ball-player is able to quickly accelerate into a 1v1 duel because he receives the ball on the half-turn. This forces the ball-side central defender into a difficult position, and in the case of Sakho & Lovren (with their naturally aggressive tendencies), will generally choose to confront the ball-player. For a successful confrontation, the central defender is forced to simultaneously attempt to close the passing lane and apply pressure to the ball-player. With sharp movements in front and behind of the defender and constantly shifting passing lanes – this makes it a very difficult situation to defend.

Build-up disconnects

The other key area the opposition were able exploit consistently in transition was behind Alberto Moreno. In general, Liverpool’s left side defense was much more porous than their right, and much of this was because of passes made behind Moreno. Whilst Nathaniel Clyne was generally more conservative in his movement, Moreno often pushed forward on the left.

![Liverpool’s softer left side (graph from [LINK]@SaturdayonCouch[/LINK])](http://com.spielverlagerung.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/07/Liverpools-soft-left-side.jpg)

Liverpool’s softer left side (graph from @SaturdayonCouch)

Sometimes this effect can also create more pressure for Liverpool’s midfielders. Because of the distance of the pass needed to reach Moreno, his direct opponent can comfortably leave more space to cover, as he will have more time to reach Moreno whilst the pass is in motion. This allows them to create a more horizontally compact midfield, and allows less space to receive the ball in midfield.

https://twitter.com/edAfootball/status/749234268212236290

Despite his good top speed, he can also find it difficult to turn quickly to ensure his direct opponent is not a threat in transition. This is due to his tendency to face towards the opposition goal whilst Liverpool has the ball, meaning he has to turn whilst his opponent faces the Liverpool goal. If possession is lost, he then has to turn before sprinting backwards, giving his opponent a head start. Even if he is facing inwards towards play from the left sideline, he still has to make a half-turn whereas his opponent can immediately move forward. When positioned on the same horizontal space on the pitch, this can make it difficult for Moreno to recover.

Once Moreno recovers, he is excellent at making tackles or recovering the ball whilst sprinting. It makes sense to utilise him in an advanced role, as this fits his skillset and the requirements of the team. But this can be fine-turned; simply by dropping slightly deeper in build-up, he could increase his influence and limit the opponent’s opportunity to transition behind him if the ball is lot.

Instead of pushing Moreno deeper in build-up though, this issue was ‘solved’ by shifting Sakho into a wider role in early build-up with a central midfielder often dropping between the two central defenders. Being situated in this wider position allowed Sakho to consistently find Moreno whilst still making his incisive laser passes into central areas. But the different midfield shape had a negative effect on Liverpool’s build-up generally – where once Emre Can would sit, now there was only space.

Of his two-man-midfield partners, neither are able to consistently add value to build-up play. Milner’s proclivity to move away from central areas means he can often only be accessed after a horizontal shift in play rather than from an immediate central pass. Whilst Jordan Henderson has improved his touch and passing ability, his off-ball movement in these phases can be negligible.

This dependence on Emre Can & Mamadou Sakho for ball progression is not sustainable for obvious reasons. This lack of midfield occupation merely gives the opposition more opportunity to counter, much like when Moreno is too advanced. Liverpool’s attacking midfielders will often attempt to fill this space by dropping deeper, and sometimes this creates some reasonably successful rotations. On the right-side Milner’s forward movements could be harnessed to disrupt opposition man-orientations with Lallana dropping into the vacant space, receiving the ball from Clyne in the halfspace. However, these simple movements cannot be relied upon to consistently progress play against strong opposition.

Offensive transitions and pass availability

With different personnel, Liverpool’s general attacking transition play varies wildly. Daniel Sturridge spent much of the season injured, but his return had a profound effect on Liverpool’s ability to consistently shift play forwards at speed. This was primarily down to his proclivity to drift ball-side (and particularly to the right) in transition. Whilst this is a strategically worse position for combination play and possession structure, it has some key advantages in transition for a player such as Sturridge.

With few opposition defenders back, drifting wide allows the opportunity for Sturridge to create a 1v1 in space. Once the ball is under control, an inward-facing field of vision gives view of the entire pitch. The lengthier nature of an ‘outlet’ pass in transition means there is also more time for the receiving player to alter his body positioning (and therefore his field of vision) whilst the pass is in motion than a standard, shorter pass.

Less capable dribblers have a tendency to remain facing their own goal when receiving the ball in the centre of the pitch. Indeed, Benteke will largely receive the ball facing his own goal regardless of his location on the pitch. As the most advanced player, it makes sense to do this – a backwards-facing field of vision allows him to view his teammates as they catch up with play. But it creates a blindspot where the opposition can press. Whilst Sturridge can move his field of vision towards the centre of the pitch as the pass is in motion, he is able to view more reference points and make a more informed decision of play. All Sturridge’s teammates can only move forwards on one side of him, whereas they could flood forwards on either side of Benteke. This can make it even harder for the player receiving centrally to assess the situation and make a quick decision, which is vital to successful transitions.

If teammates are not able to progress as quickly as play, Sturridge is capable of shielding the ball or utilising sharp dribbling movements to move beyond his opponent. This is again made easier by the 1v1 created as he drifts into a wider position. With the movement wide disrupting the opposition’s horizontal compactness in defense, even if a 1v1 is unsuccessful then onrushing teammates will have more room to operate if Sturridge can make a pass to them.

Sturridge is not the only Liverpool player with a multi-dimension skillset in offensive transitions. Divock Origi has vastly improved his timing of runs in behind, and his new-found strength makes it easier for him to keep Premier League central defenders from slowing him down in a tight tussle. Sadio Mane provides a huge transition threat, and had been invaluable in these situations at Southampton & Salzburg. Sturridge’s inclination to drift wide benefits Mane’s preference to move beyond the strikers (with a preference of starting on the left and moving inside).

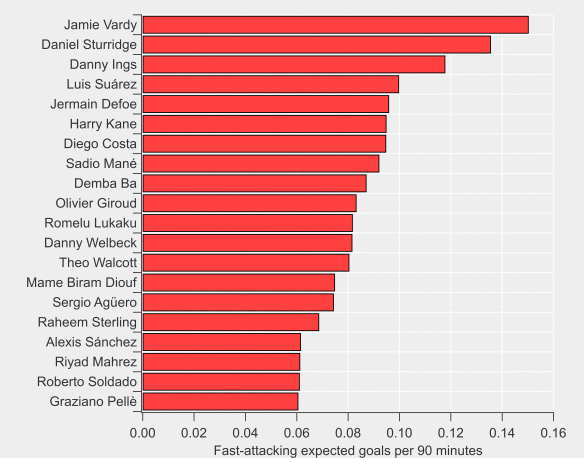

Danny Ings missed much of the 2015/16 season with injury, but is one of the top transition forwards in the league. Much like Sturridge, he is capable of playing as the outlet or reacting to an initial break and offering immediate support, with a fast-paced movement into the centre.

Top 20 players in terms of fast-attacking expected goals per 90 minutes over the past four Premier League seasons. Minimum 2,700 minutes played. Three 2016/17 Liverpool players feature – here comes the speed. (Graph courtesy of @WillTGM)

Jurgen Klopp famously said that the counterpress is the best playmaker. Despite an improved counterpress, the quantity of Liverpool transitions from these situations has not dramatically increased. This is perhaps a downside of the ‘space-oriented’ counterpress that Klopp operates with – when the players do not fully understand the system, there tends to be an emphasis on aggression over structure. If the pressing movements are not staggered, then this leaves few potential passing options once possession is regained.

This clean regain of possession improved in general pressing, particularly with the blind-side tackling from Lallana & Firmino. But there are still improvements to be made. Feeding off passes from second balls and broken possessions was also one key reason Gotze found such success in Klopp’s system at Dortmund…

The Future: 4-4-2-0?

It is clear that many improvements have been made since Jurgen Klopp’s arrival on Merseyside. In terms of counterpressing and general pressing structures, this team is now totally different than the one that started the season under Brendan Rodgers. There seems to be more focus on adapting the system to individual challenges & fixtures, rather than completely ditching a style or system after a few bad results.

One such system that was only explored briefly throughout the season, was a 4-4-2/4-6-0 used against Aston Villa. This came immediately after the controversial Sunderland match (due to a fan walkout at ticket prices and Klopp missing the game due to illness) where Liverpool utilised a heavily rotating midfield to counter Sunderland’s emphasis on man-marking.

Situation from the Aston Villa match, and how Milner could have adapted his positioning to occupy the opposition central defender – perhaps with a more capable striker, even both central defenders could be occupied.

Having utilised a 4-3-2-1/4-3-3 system against Sunderland and in recent matches, it was suggested the same would be used. Against Aston Villa, though, Liverpool were able to utilise Roberto Firmino & Daniel Sturridge at the same time for the very first time that season (25 league games in). The natural movements of both players are to drift from a traditional centre forward position.

One such situation is both players drifting towards the ball-side halfspace. This allows for improved combination play in those wide areas that Liverpool began to focus on more, and an even more aggressive counterpress if the ball is lost. It can cause chaos against man- or zonal-focused systems, and produced Liverpool’s best performance of the season as they thrashed Villa 6-0. Against a man-oriented system, the fluidity of movement creates a natural difficult challenge for defenders to constantly react to. Against systems with stricter zonal marking, it presents an opportunity to overload the zone and utilise combination play in a tight area.

But this wide movement of the strikers must be compensated with movement from other players. This is something assistant manager Peter Krawietz had talked about previously when asked about the use of a ‘false nine’ (quote translated from his interview with SPOX in 2012):

“It is possible that in case you break through on the wing, the centre is under-manned. This was observable in the Champions League semi-final between Barcelona and Chelsea. The Blues blocked the centre with eight or nine guys, and Barca could only break through the wings. But then in the middle, not enough happened. The advantage: you can turn it around.

It is possible to occupy the centre flexibly and run into it with different players with high tempo movement, which deprives the oppositional centre backs of access. When the ball arrives, you can occupy the relevant spaces with many players, creating an ‘ambush’. That is clearly the positive aspect of this arrangement.”

In the match against Aston Villa, James Milner was often the player tasked with occupying the opposition central defenders when Sturridge & Firmino both shifted away from that area. Lallana has been used in a similar way on occasions throughout the year, but it may also present some of the key reasoning for the signing of Sadio Mane, who operated in a similar way during his time at Southampton.

https://twitter.com/edAfootball/status/749344876236505088

He has the added advantage of lightning top speed, but Mane’s agility and acceleration is particularly outstanding. This means he can quickly adapt and adjust his movement to play, beating his direct opponent to the ball. As well as making him adept at occupying opposition central defenders, it also ensures he is a consistent threat in counterpressing situations. Mane’s manager in Salzburg, Roger Schmidt, famously utilised an alarm clock in training that went off five seconds after conceding possession if the ball was not yet regained.

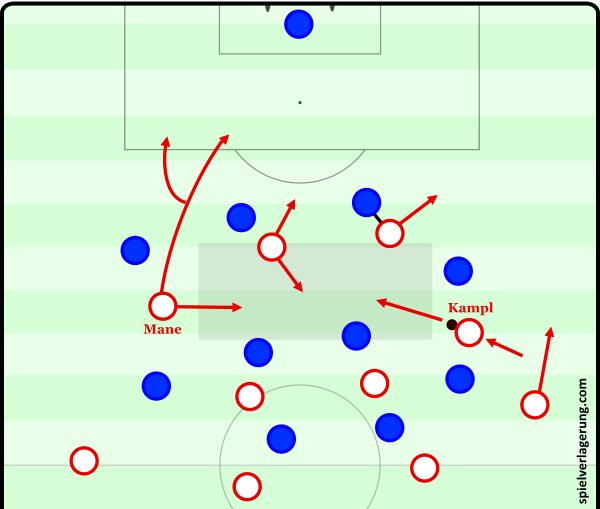

Mane’s time at Salzburg was spent mainly as an indented winger on the left of Schmidt’s flexible 4-4-2/4-2-2-2 system. Being able to adapt to the movement of his teammates was another key strength developed during this time. With such outstanding pace, it was often expected that Mane would focus only on making movements behind, but after a shift in play he provided a valuable passing option for combination play after indenting infield. Particularly when the strikers remain in their traditional advanced position, Mane is capable of combining with teammates in the ’10 space’ for spectacular results.

Variable movement in Red Bull Salzburg’s 4-4-2: Mane often played a key role in combining play in the ten space, but also able to adapt to backwards movement from striker to make movement in behind defense himself.

These variable movements are a major strength of another rumoured Liverpool target: Mario Gotze. Despite the obvious differences in play-style and effect on the team, this key feature makes them both suitable as indented ‘wingers’ in a 4-2-2-2 system. There could still be a place for Gotze (or a similar player), who would have a massively positive impact on the team’s ability to re-structure in attacking organisation.

In this way, Gotze presents a different profile to Liverpool incumbent Philippe Coutinho. The Brazilian provides valuable progression in early build-up phases, where he can dribble or make quick combination plays in the halfspace. But in attacking organisation, he finds it difficult to make consistently helpful movements, particularly with his back to goal. Gotze differs from this, whilst also being just as useful in early build-up due to his similarly high press resistance. He can make intelligent movements out of cover shadows, and more effectively adjust to his teammates and the opposition. This becomes particularly useful during a sideways shift in possession (such as the scene illustrated above) or when adjusting quickly to a new in-game situation.

Firmino & Sturridge only started four more games together throughout the rest of the season, and Mario Gotze seems more likely to return to Dortmund. But the deadly potential of these personnel combinations suggest Liverpool may not be far away from something great. Particularly down the right side, where Sturridge naturally prefers to drift towards anyway, a number of dangerous combinations could be created.

Conclusion

With the arrival of managerial megastars Guardiola, Mourinho and Conte, the top of the Premier League may look very different next season. Leicester will hope to continue their outstanding form that led them to a Premier League title, and Arsenal & Tottenham will both provide serious challenges to the top four.

Liverpool will have to improve to even be in contention. This improvement has been occurring consistently since Klopp’s arrival, and the addition of players over the Summer will provide valuable reinforcement. Klopp and his staff seem to have concocted a more suitable fitness regime for Daniel Sturridge, who has spent most of 2016 available. Many players with long-term injuries will also return to full fitness over the Summer and bolster the squad.

After a disappointing loss in the Europa League final to Sevilla, Liverpool find themselves without European football for next year. This will significantly reduce the long-term fitness load on the players during the latter stages of the season. Of the other top Premier League teams, only Chelsea have a similar advantage.

If the team can continue their progress and further advance their approach to fitness without the valuable winter break, then there is no reason Liverpool cannot take a major step next year.

Big thanks again go to those who were happy to share data or other information for this article, be sure to make use of the links throughout this piece to access their respective Twitter accounts. Also thanks to @MC_of_A and @GoalImpact for providing additional data.

9 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Igor November 23, 2016 um 8:57 am

Excellent article, keep it up guys! There is whole bunch of nonsense in the world of football/internet and this is really breath of fresh air 🙂

However, If you could write an article on “How To Analyze A Game” I would be extremly happy :). I have a problem when I watch a game and trying to analyze it. It seemed a lot easier to analyze a game when I was not so into tactics and knew a lot less than know. Key questions for me would be:

1. Can you analyze a game just by watching it on TV? Do you need aditional insights from, eg, Opta? Ok, I know you do not need Opta, but how do you do it?

2. Football game is very complex, so many things are happening at one moment and I do not know on what should I focus and how to structually approach game analysis. Do you focus first on defence of one team, then defence on other team etc…

3. How many occurences of one event would you expect to happen in order to be able to argue specific tactics are used? For example, lets say you watch a game and see CM was using man-oriented zonal marking, but you saw that just 3 times…is it enough?

I know, you cannot give me specific answers to my questions, hopefully I could clarify what are the issues for me at the moment.

tobit November 25, 2016 um 12:19 pm

I’m not an SV-Author, but when I started analyzing games I tried to focus on only one aspect in one team at first. For example I tried to describe the situational formations of a team in pressing and deep defense.

In general: base formations are relatively easy to recognize so I would always try to figure them out in the first minutes of the game and try to memorize the position of each player so I can easily find out where a player moves on the ball by listening to the commentator.

Next thing I do often is to look at the deeper build-up phases and the corresponding Pressing-moves of the opponent because they give me a good idea of the style the teams are playing (e.g. slow, possession-focussed vs. fast, transition-focused).

The most difficult part to me is describing what’s happening in attack around the final third because there is so much to see and it often looks far more chaotic than the deeper build-up-phases. I often try to find out which players tend to do what (e.g. third-man-runs, overlaps, dropping) and wether there are asymmetries (e.g. one winger on the touchline and the other moving inwards).

I think they published something about that thema in german at spielverlagerung [dot] de.

Faysal August 14, 2016 um 11:20 am

Wonderful, wonderful read. I always appreciate the use of figures, diagrams, video clips and graphs in order to further explain and/or prove the body of text – and I have noticed that in the past few months the usage of them has been more effective.

I have one request; can you please carry on these season-previews for all the top teams? I want to use this premier league season as a strong case study to improve my tactical knowledge and observe how many of the top coaches in the world adapt to competing with one another and tactically evolve as the season passes on and necessity forces them to.

Furthermore, as an amateur, I have noticed some general tactical similarities between three of my favourite coaches this season in the PL: Klopp, Conte and Pochettino. Primarily, the clever usage of space both in attacking and defensive phases of play, the intelligent usage of pressing in different waves from different lines of defence, and the fast, direct combinations their attacking players make. I would love if you would be able to/interested in comparing all three general game models at some point this season, analysing the similarities and contrasts of each system, and why these systems were chosen with regards to extracting the most effectiveness out of the available personnel.

Russell July 26, 2016 um 7:57 am

Excellent article. The best piece about Liverpool I’ve read in a very long time. Could you please tell me where you sourced the data about counterpressing in the following graphs, and whether this data can be accessed by the likes of myself?

‘Progression of Liverpool’s counterpress over the 2015-16 Premier League season’

‘Percentage of all potential counterpress opportunities in the opposition half that occurred on the wing’

‘Individual counterpressing contributions, and effect on the team’s ability to regain possession quickly’

Thanks.

Ollie July 21, 2016 um 3:40 pm

Great article, I have a particular interest in the tackling techniques you discussed, where a player hops into the tackle. Would you be able to elaborate on this, or have any specific video examples of this technique in use? Thank you, Ollie.

August Bebel July 21, 2016 um 7:40 am

Great stuff here. I’m really glad to see a confirmation that Allen is a great player. He had a very good Euro, too, but it does not seem like Klopp appreciates him.

tobit July 21, 2016 um 7:02 pm

He’s not the type of midfielder Klopp needed in his first 9 months at Anfield. Kloop mostly used more physically strong players due to the Premier-League-habit of having real powerhouses in midfield-roles. He needed his CMs to be strong in the terms of long-distance-runs and face-to-face combat to win back the ball after all the turnovers his team produced due to their vertical passing.

Maybe we will see a different – more dominant – approach in some games next season but I doubt it will be their common way of winning games.

August Bebel July 22, 2016 um 9:37 am

The statistic about counterpressing suggests that even though he’s physically not that strong Allen was great at winning back possession, the best by far in the team. But it looks like he’s being sold to Stoke anyway.

tobit July 23, 2016 um 9:19 pm

It might psychological that you would rather use more physical players against the likes of Toure or Sissoko even if the stats tell you a better option.

Another “downside” of Allen is his rather horizontal passingstyle – he clearly prefers to combine in deeper midfield – whilst Can / Henderson / Milner like to move the ball up the pitch quickly and then run after it to receive layoffs from Coutinho / Lallana / Firminho.