Atletico Madrid shutdown Valencia

A match-up of the second and third place teams in La Liga, in the form of Simeone’s Atletico Madrid and Marcelino’s Valencia. In a hotly contested match, Atletico showed why they are the top defensive side in Europe at the moment, holding Valencia to 0 shots on goal for the whole match.

These two managers contrast the common perception of Spanish football being free-flowing and attack heavy, as their teams embody industrious play and present many difficult defensive challenges for their opponents. The attacking talent found in their teams contribute to both sides of the ball immensely, such that the front of both Valencia’s and Atletico’s teams serves as the beginning of their defense in addition to their source of goals. In addition, both of them deploy similar strategies within their 4-4-2 formations, adding tactical intrigue for this match.

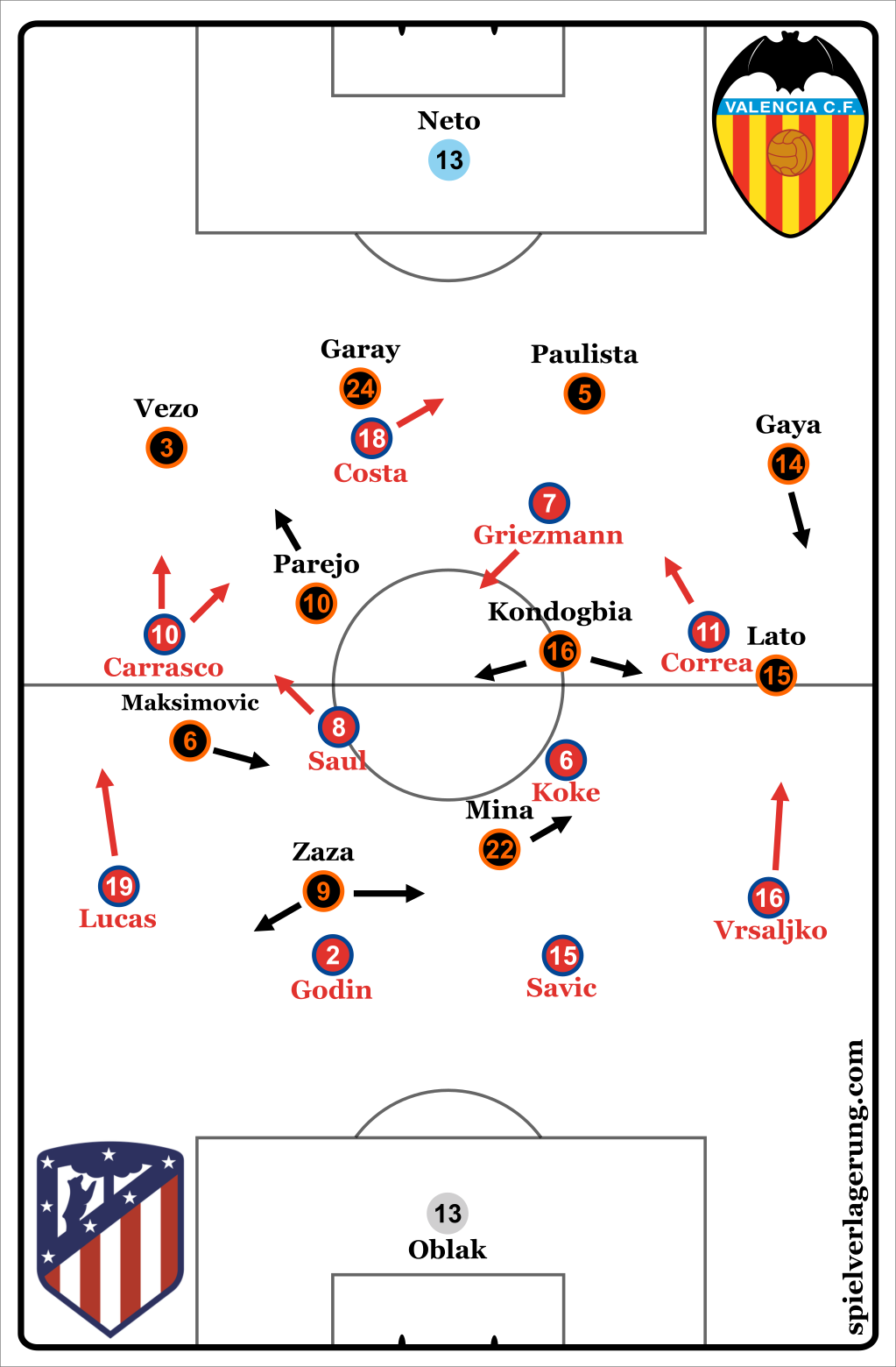

Starting XI’s. (Note: Savic is replaced by Gimenez 30 minutes in due to injury, while Juanfran enters for Godin just after halftime for the same reason.)

Without The Ball

Given both manager’s reputations as paragons of strong defensive play, the moments spent by each team without the ball are of more significance from an analytical point of view. Besides, the match all in itself was not loaded with top drawer attacking examples. This is largely due to the strategy and personnel that each manager deployed. For example, partially due to injuries for Valencia, traditional full back Toni Lato was deployed on the left side of midfield. Combined with how each manager approached this match, and it was always bound to be a cagey affair.

Atletico

Diego Simeone had his team prepared so that they could implement a high press during the early stages of Valencia’s build up. During attacks beginning in Valencia’s defensive third, Costa and Griezmann would occupy positions approximately 10 meters from the centre backs and apply pressure if they were within 5 or 6 meters of the player with the ball. When Garay or Paulista had the ball, their cover shadows would block off the centre of the pitch, aiming to eliminate passes into Parejo or Kondogbia.

Valencia rarely looked to use Neto in their buildup, so Costa and Griezmann didn’t find it valuable to prevent passes into the Brazilian. As a frame of reference, their line of confrontation was about 25 meters from goal. Further up the pitch, Koke and Saul engaged in man-oriented coverage of Valencia’s central midfielders. Their movements were predicated by the player they were covering, but the Spanish duo never veered from the centre of the pitch to follow them. When Parejo and Kondogbia ventured away from them either deep or wide, one of the forwards would move towards them, making a numerical equality around the ball and numbers up in the areas that Valencia wanted to target.

The outside midfielders for Atleti were instrumental in the execution of their plan on the evening. Each of the outside midfielders would be in the halfspaces while Valencia had possession, sprinting to the ball once the ball was passed to the outside backs. There was a particular focus on Valencia’s right side in Atletico’s pressing, likely a natural byproduct of Valencia’s build up frequencies (to be mentioned later). Either way, regardless if it was planned or natural, the cue of Vezo receiving the ball prompted Atleti to ramp up their pressure and force him wide with his decision making. With the tight pressure of Lucas on the wing, combined with the limited area found on the wings, the right touchline was a frequent area where Simeone’s team recovered possession. Through engaging Valencia higher up the pitch, this forced a higher speed of decision making than usual, leading to a handful of errors in possession that were harmful in the long run.

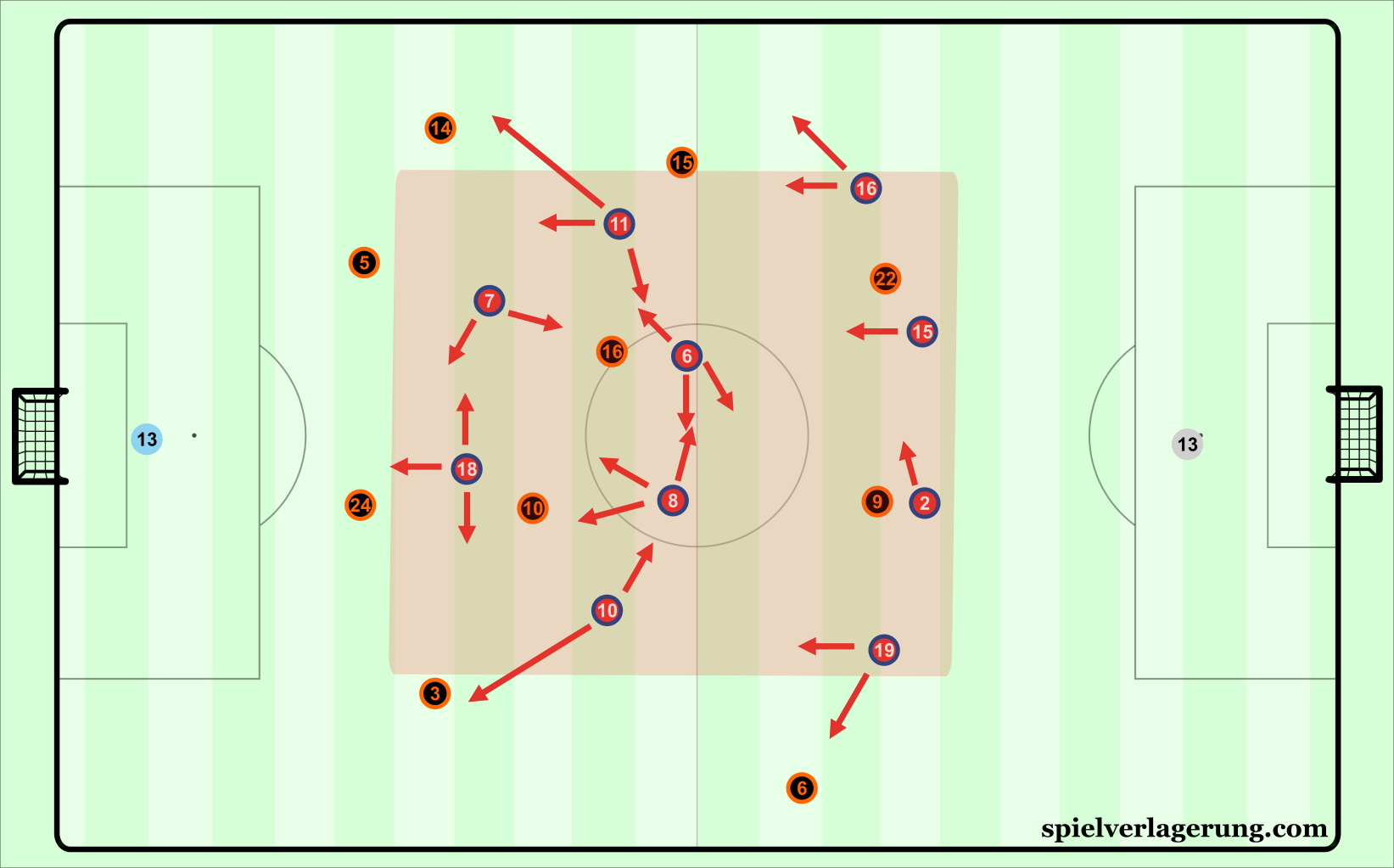

Atletico’s common defensive movements during the match, with the area they seeked to control highlighted.

For the moments where Valencia found themselves moving into the home side’s half, Atletico’s defensive structure and strategy was largely unchanged from how they traditionally play, with the forwards lining up at the bottom of the center circle (from Oblak’s point of view) and the same emphasis on forcing the opponent wide during attacks to lead to crosses in the box. These can easily be defended by Savic and Godin, so they hardly posed a problem throughout the evening.

Valencia

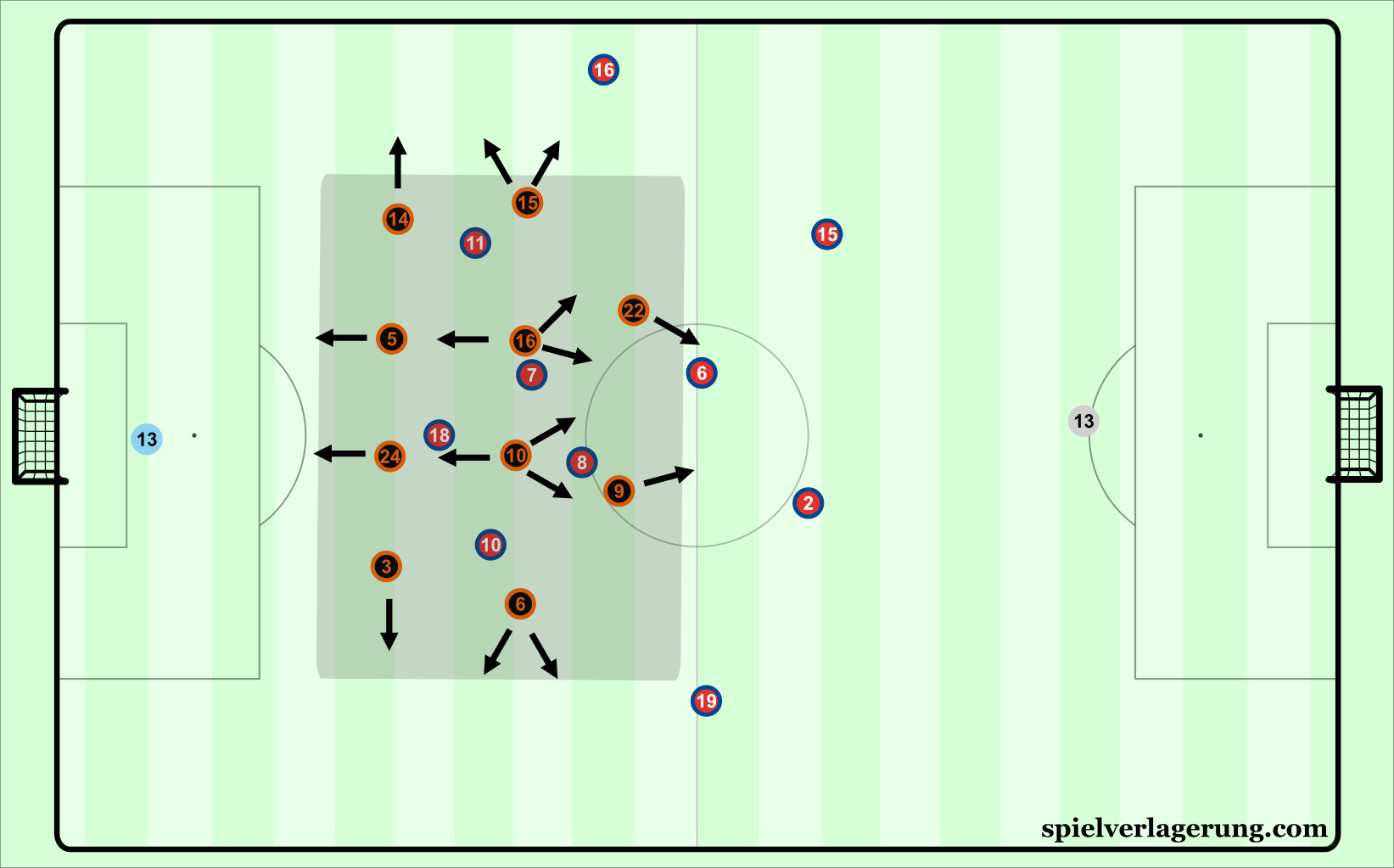

Marcelino preferred his team to cover deeper areas rather than pressure Atletico’s defense. In particular, Valencia hardly ever managed to legitimately pressure Atleti inside their own half. Valencia elected to organize in a medium-low block, setting their offside line approximately 35 yards from goal. Their defense and midfield occupied similar positions to Simeone’s team, with the outside midfielders in the halfspaces and strong horizontal compactness.

Where Valencia differed just slightly from Atletico was their emphasis on vertical compactness. The midfield and defensive lines were quite close together in their defensive organization, leading to central crowding during Atletico’s possession. They were much more content with conceding space to the home side, preferring to maintain their shape than move up to pressure and potentially create openings for the attacking quality to expose. The only time they would move up is following a backwards pass near their own penalty area, done to make any players waiting for a pass in behind or a cross offside. It was only in these instances that Valencia were proactive in their approach against Atleti.

Valencia’s general defensive movements, with Marcelino’s preferred area to control highlighted in black.

At times, this led to deep moments of defending around their penalty area. For the most part, Marcelino’s team were more hesitant to pressure than Simeone’s group, as they often back up when confronted with dribblers. This was in contrast with Atletico who frequently fouled higher up the pitch to dispel momentum or prevent dangerous attacks. Valencia opted for higher degrees of control for the moments when Atletico were in possession, with the view of using their deeper positioning as bait to commit Atletico too high up the pitch. From the moments they would win possession, they hoped to counter via Zaza and Mina. But since they defended so deep, these attacks rarely had any foundation behind them, and Valencia were often pinned back as a result. They spent a large portion of the match out of possession in this state (Valencia had approximately 55% possession).

Valencia’s Frustrations and Possible Solutions

Valencia had no success in beating Atletico’s defensive scheme, aptly indicated by both the scoreline and their shot total. Injuries certainly have a part in the reason why Valencia did not put in their best performance, but there were other issues that stemmed from the positional structure and player habits as well.

First we’ll start from the back of the team, particularly the solution that Dani Parejo used to get the ball from his defenders. Parejo chose to drop deep while the centre backs were on the ball, providing the outlet in the form of an extra player to bypass Costa and Griezmann. Sure this is fine if the corresponding movements from his teammates are aimed at receiving the next pass forwards, but this was rarely the case. Instead, Kondogbia was often too far away to receive the next ball and retain possession.

The centre forwards were primarily focused on getting in behind, neglecting a function of being vital options in the attacking build up. Zaza was frequently too fixated with the ball for his movements, moving too close to teammates in his attempts to receive passes, consequently disrupting Valencia’s positional structure. In particular, his movements were often too close to the wings, oftentimes running diagonally toward the touchline to receive passes. On the other hand, Mina was too pegged to the left halfspace. This left a large gap between the two of them, leaving no central presence during phases of Valencia’s attack. The pressing of Atletico in these wide areas made all of these movements illogical and inevitable that Atletico would succeed.

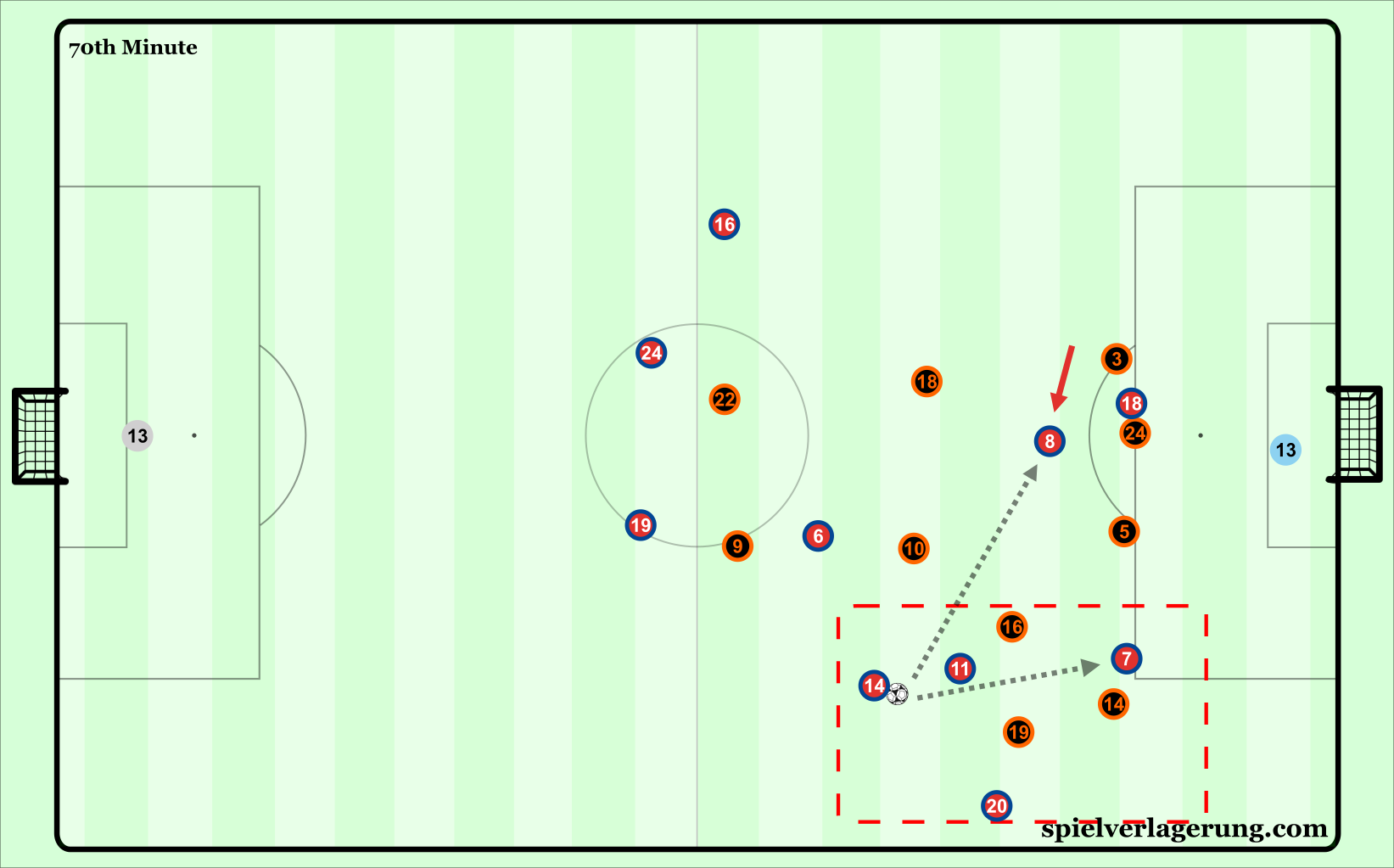

This left Parejo with ultimately one suitable option that was risk neutral, but detrimental overall, in playing the outside back. Afterwards, Atleti would initiated their press, and Valencia’s attack would stall as a result of the lack of support for Parejo. Many of the ensuring errant passes originated from Vezo, who struggled during the match.

Because of Atleti being able to easily access Valencia’s next passes, Vezo has few good options on the ball and ultimately gives it away. If Mina (22) checked into the space rather than ran in behind, better options on the pitch could’ve appeared.

A solution that may have worked better would be to have Mina drop closer to Parejo and act as a link in between the lines. When moving at the right times, he would be able to create just enough room for himself to receive the ball. The incoming pass must arrive at his feet as he separates, since Godin and Savic would remain touchtight to Mina at all moments during the match. In order to have some sort of quality result, one player (most likely Kondogbia) should begin his movement towards Mina as the pass is played. These sort of quick three-man combinations were hardly done by Valencia, and in the one moment they did before halftime, it almost resulted in a high quality chance.

This may result in Valencia’s midfielders being pushed to the same side and not having any option to switch the ball, but when trying to play forward against Atletico, it is a risk that might have to be taken within the confines of 4-4-2. For zonal occupation purposes, the wingers can occupy the halfspaces and move centrally if one of the midfielders moves wide, rather than be so orthodox in their positioning on the touchline. The fullbacks can utilize the wings and provide width in that form. Gaya, one of the most promising fullbacks in Europe, was not very adventurous in the match, and the attacking contribution of Valencia’s fullbacks paled in comparison to Vrsaljko and Lucas. By being more risky in wide positioning and bolstering the advanced central numbers, Valencia may have had more success against Simeone’s defense.

Other ways that Valencia attempted to beat Atletico were through the dribbling of Kondogbia, which was often met with harsh tackles and fouls from the home side, alongside some sporadic long passes forward that were not retained. The passes down the wing seldom worked, but when they did, Valencia seeked to create chances via crossing into Zaza and Mina, which was dealt with easily.

Atletico’s Attack

Against Valencia’s deep block, the individuals of Atletico were the decisive factor when it came to getting 3 points. But, there were some noteworthy trends about how Atletico attacked, primarily for their chance creation. Griezmann was given a free role in all areas of attack, wandering around the pitch in the name of being the extra player around the ball as a solution forwards. Most often, he would go into spaces a #10 would occupy, just in front of Saul and Koke. The outside midfielders would pinch inside and high, using the horizontal gaps in between the fullback and centre back as a reference. Atleti’s fullbacks then moved high to support whenever the midfielders were in possession, forming a quasi 4-3-3 depending on Griezmann’s location.

The central congestion of Valencia channeled most of Atletico’s attacks into wide areas. Briefly mentioned earlier, the fullbacks were instrumental in how Atletico attacked. It was commonplace for there to be wide combinations between the fullback and the corresponding winger, or for the fullback’s late support to not be tracked by Valencia’s wingers. These brief moments of superiority were central to Atletico’s strategy, as they were the primary source of crosses in the penalty area. The far side winger would join Costa to challenge in the air to supplement these chances.

Atletico’s most successful attacks were found when players got in Valencia’s gaps in between defenders. With Griezmann’s freedom up front, they were able to create man advantages that led to some productive attacks in the 90 minutes. Rather than play Saul or Griezmann, Gabi recirculates possession to be conservative with their lead.

Crosses were the main form of chance creation, as little could be generated centrally as a result of the congestion of Valencia’s defense. When probing the away side, Saul and Koke frequently serve as the fulcrum for switching from one side to the other, with the ball essentially being a pendulum. This U shape of circulation was at times frustrating, but it was the only way to play to open spaces against Valencia and ultimately served Atleti’s strategy focused on attacking from wide positions.

From the center zones, Griezmann’s freedom hardly led to attacks from the middle. Instead, the most common form of good chances of Atletico was from long range shooting. Since Valencia kept dropping and dropping, Atletico were given ample time to attempt strikes from distance. Neto had most of these under control, except for Angel Correa’s impressive strike in minute 58. From then on out, Atleti were conservative in their approach, satisfied with their lead and managing the match.

Conclusion

In the battle of nearly identical playing systems, it isn’t shocking to find that the team with the better core of players edged out the victory. Diego Simeone during his tenure at Atletico has largely remained the same with his tactics, making small adjustments over time. His defensive record over the years speaks for itself, so major off sweeping changes are not required. When it comes to beating the Argentinian, a bit more risk is required than what Marcelino’s team demonstrated at the Wanda Metropolitano. Imitation may be the most sincere form of flattery, but it won’t lead to beating the master at his own game without the proper adjustments.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen