RB Leipzig: Successful displays in the first half of the season

Eleven wins, three draws and two defeats. RB Leipzig have surprised many spectators and pundits with their successful run in the Bundesliga so far. After explaining their football philosophy in a previous article, we now examine a few successful displays in recent months.

Wolfsburg’s wing play causes problems for 45 minutes (16/10/2016)

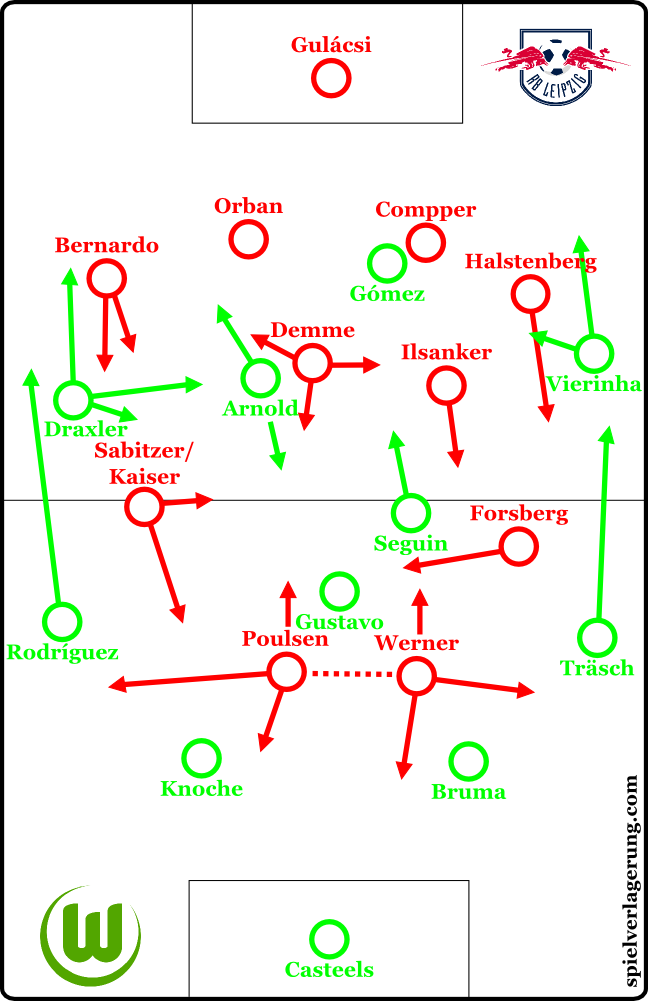

Hosts VfL Wolfsburg employed a widely shaped 4-2-3-1/4-1-4-1 in which the roles in midfield were very clear, with Luiz Gustavo as a No. 6, Paul Seguin a No. 8 and Maximilian Arnold a No. 10. The Lower-Saxons used a 4-4-2 pressing and made inside-out runs when pressuring Leipzig. Behind the two players upfront, two lines of four waited to negate Leipzig’s attack.

Yussuf Poulsen and Timo Werner stayed close to the sole No. 6 when Leipzig were in pressing mode to apply pressure using the mechanisms explained in our previous article. Usually, the Roten Bullen were successful and Wolfsburg’s defenders had to stop and reset for a new attempt to move the ball forward. That also led to a penalty for Leipzig, as Werner switched sides with Poulsen and chased a backwards pass which forced Koen Casteels to commit a mistake. Emil Forsberg, however, missed the penalty.

Yussuf Poulsen and Timo Werner stayed close to the sole No. 6 when Leipzig were in pressing mode to apply pressure using the mechanisms explained in our previous article. Usually, the Roten Bullen were successful and Wolfsburg’s defenders had to stop and reset for a new attempt to move the ball forward. That also led to a penalty for Leipzig, as Werner switched sides with Poulsen and chased a backwards pass which forced Koen Casteels to commit a mistake. Emil Forsberg, however, missed the penalty.

Wolfsburg usually intended to play through their left side, where Robin Knoche and Ricardo Rodríguez could maintain ball possession thanks to their technical skills and reset the build-up play or knock the ball forward. Long balls created dangerous situations for Leipzig here and there, as Wolfsburg were relatively successful with their counter-pressing and moved the ball towards the touchline quickly after turnovers, which then brought Julian Draxler and Vierinha into play who bombed down and cross-passed to Mario Gómez.

Moreover, fast-paced passes down the wing received by Wolfsburg’s wingers who normally made a few steps backwards meant trouble for Leipzig’s full-back in the early stages of the match. Because of the high position of Leipzig’s wingers, both full-backs were forced to push forward, though it was difficult to get the timing for these runs right, which was something Draxler tried to take advantage from by making use of dynamic dribbles contrary to the movement of Leipzig’s full-back. Immediately afterwards, Draxler intended to cross-pass the ball onto the other, rather uncovered side where Christian Träsch and Vieirinha waited as open receivers.

Ralph Hasenhüttl adjusted the player roles in central midfield midway through the match. Diego Demme became more ball-oriented in his actions and was supportive on both wings or attacked the lines in front of him aggressively. Stefan Ilsanker served as a balancing player in the middle. In the meantime, Leipzig did not continue to pressure Wolfsburg’s early build-up as intensively. Instead, both wingers stood deeper in the second half to help defend the opponent’s wing attacks, which gave Leipzig more control over the game while Wolfsburg struggled more and more as time went on.

After Leipzig’s first goal, Dieter Hecking brought on a second striker and his team started overloading the zones upfront. Leipzig, however, kept their 4-2-2-2 in that tricky situation and did not field a back five or back six, which a lot of teams would have done in similar circumstances. Thanks to ball-near compactness and goal-oriented defending behind the pressing lines, Leipzig were able to keep the lead until the final whistle.

A scene that showed Leipzig’s potential weakness in case they cannot direct the opposing build-up and protect the first pressing line: 1) Sabitzer was oriented towards the full-back, while Ilsanker was not able to shut down the passing lanes into higher zones. 2) The rest oft he defence did not outnumber the opponents in goal-near spaces. They are even 4 vs 6 close to the offside line.

Dominance over Mainz 05 (6/11/2016)

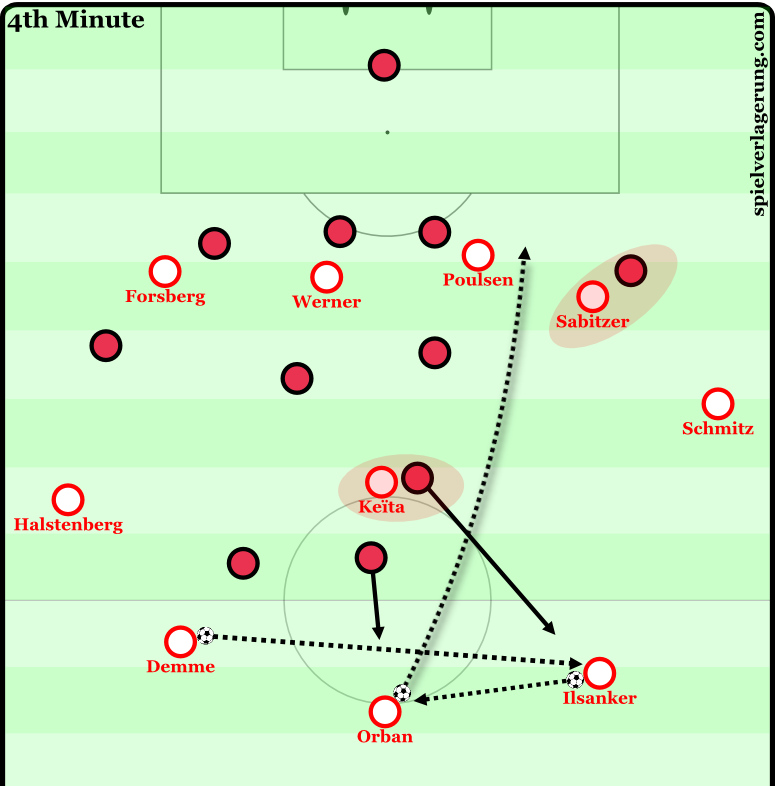

The home game against FSV Mainz 05 started in a positive way for Leipzig. After only three minutes, the Saxons picked up the lead and found themselves in a strategically advantageous position. Mainz employed a customary 4-2-3-1 and did not let any midfielders drop back in the early build-up phase.

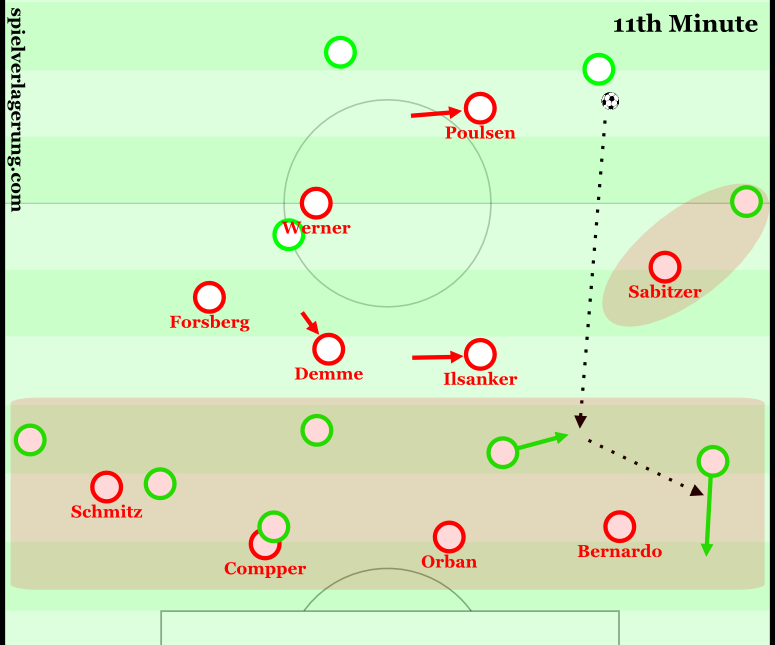

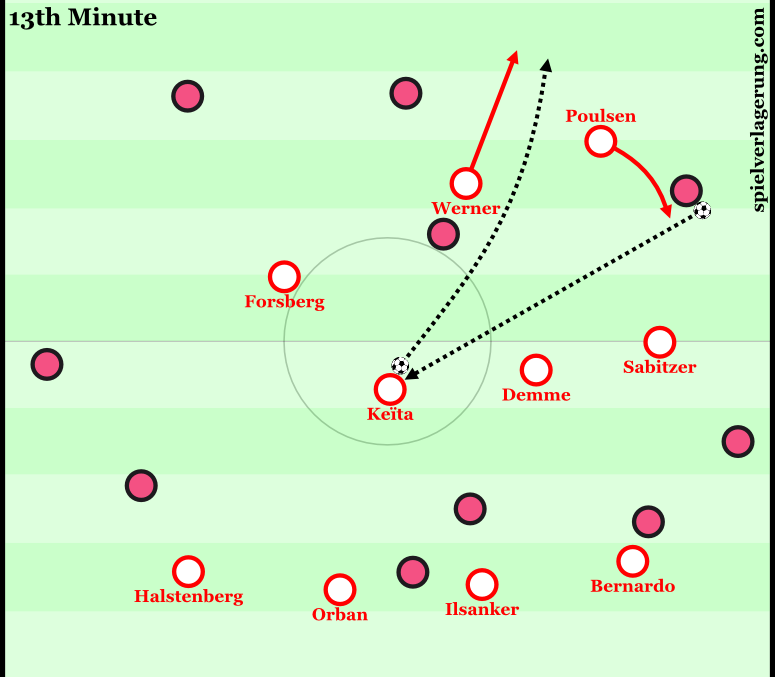

The starting position of Leipzig’s pressing formation was rather deep, because both centre-forwards were close to the opposing centre-midfielders and waited for a horizontal pass by one of the Mainz defenders. Then Leipzig’s ball-near winger started the attack and both strikers stepped forward in order to block the centre. The tactical triggers once again depended on the viewing direction of the opposing players involved in the build-up play.

At first, one central defender turned towards the touchline, causing Leipzig’s ball-near winger to move forward. That particular player tried to came from an outside angle to force an inside turn by the opposing receiver. Subsequently, both centre-forwards started their runs. The forward runs by Poulsen and Werner were covered by the man-oriented movement of both centre-midfielders. Naby Keïta, in particular, marked Daniel Brosinski very closely in the second phase of Leipzig’s pressing.

Mainz preferred to move the ball quickly down the wing. The receiver of the ball, however, had no chance to turn around because of Leipzig’s immediate pressure. Additionally, Leipzig’s centre-midfielders smartly stepped into the ball-near half-spaces, thus covering diagonal passing lanes into the centre avoiding quick cross passes.

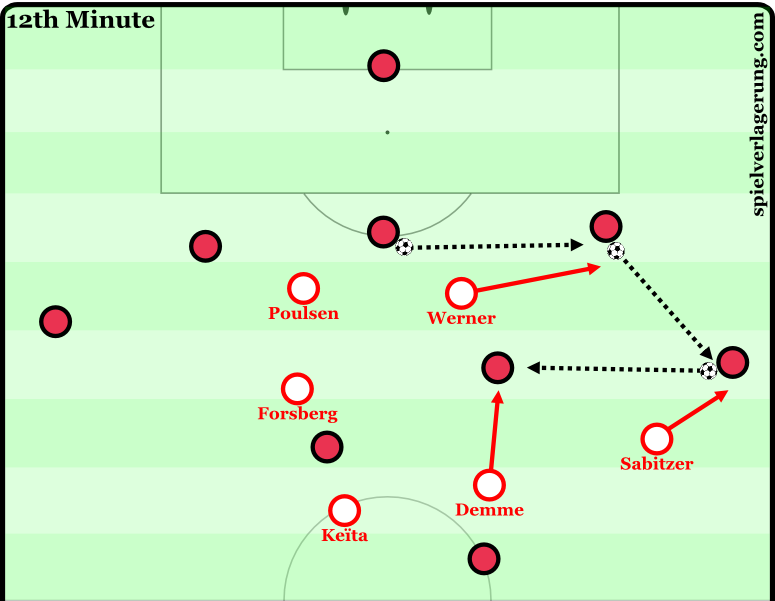

During their build-up play, the Roten Bullen outnumbered Mainz’s first pressing line only a few times. Instead, Hasenhüttl’s side wanted to play the ball quickly into the half-space. By not using an additional player at the back, Leipzig had one more man at the halfway line. Layoff passes by Poulsen and Werner and Keïta’s and Demme’s clever movement within the half-spaces were the basis for fast-paced attacks against Mainz’s passive chains. A three goal lead at half-time made clear that Leipzig were overmatching Mainz on that day.

Cool, calm and collected against an unorthodox Freiburg side (25/11/2016)

At the end of November Leipzig travelled to SC Freiburg, who decided to make use of a back five and an interesting yet unusual pressing structure. Christian Streich’s side defended in a 5-2-3/5-2-2-1 shape, where both secondary strikers kept an eye on Keïta and only left their positions when one of Leipzig’s widely positioned build-up players received the ball.

Leipzig normally added Demme to the back line when building up attacks. Even both full-backs remained in deep positions, which let them outnumber Freiburg’s first pressing line. Midway through the match, Keïta started changing his initial position in the early build-up. Sometimes he switched positions with Demme or dropped back which, however, created an ineffective 6-0-4 on occasion. Alternatively, Keïta kept some distance to Freiburg’s high block and pulled one of the opposing centre-midfielders away from his spot in the formation.

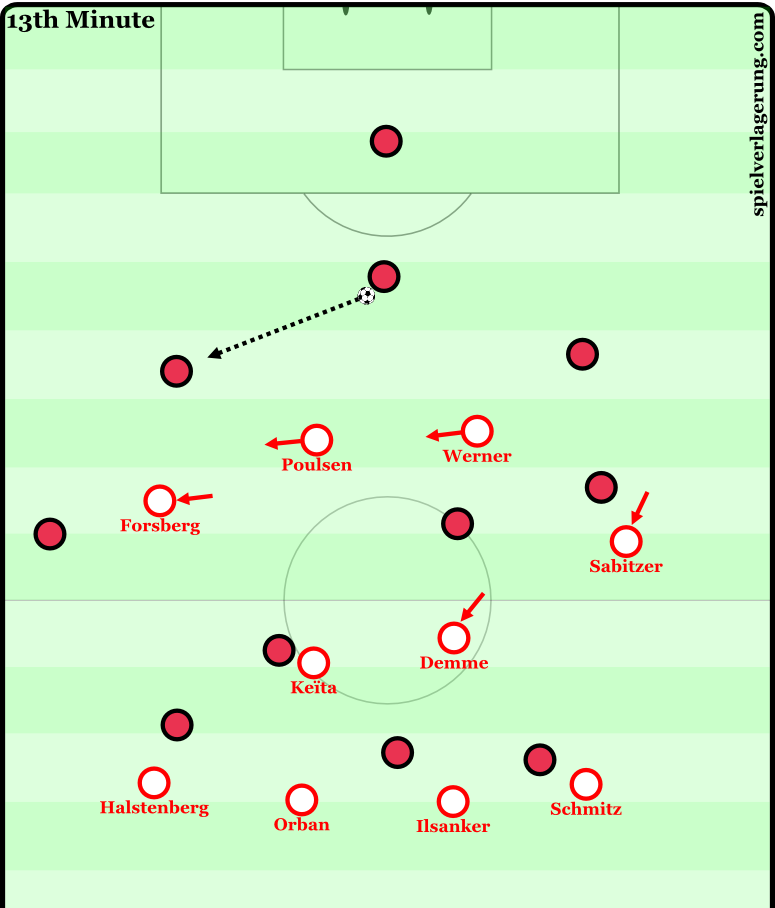

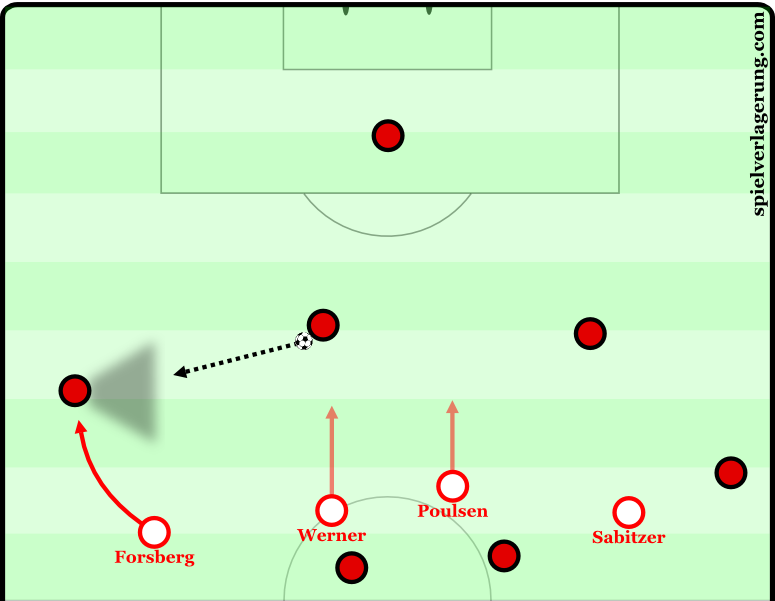

The Saxons constantly found ways to bypass Freiburg’s pressing—from quick combinations through the full-backs to long balls into the half-space holes upfront. The early lead came after a long-distance shot by Keïta following a corner, though. Freiburg’s equaliser did not unsettle Leipzig by any means. They kept their composure and followed the plan which included two pressing variations. Either the centre-forwards ran outside-in close to the defenders so they could direct passes towards the touchlines and trigger forward movement by the teammates behind them, or the entire formation was deeper, while Poulsen and Werner shut down the passing lanes towards Freiburg’s centre-midfielders.

In this scene, Demme’s forward movement is particularly interesting. Prior to him coming forward, Leipzig pressured very early. Werner and Sabitzer once again behaved smarly when attacking in order to direct the opposing build-up play as desired.

A minute later, Leipzig defended deeper against Freiburg’s build-up structure including three centre-backs.

Demme and Keita’s positioning was key when those two wanted to win rebounds. Not only did they assist the second goal following a quick counter-pressing attack, but Leipzig also dominated the match thanks to their ability to pick up rebounds caused by long balls. Moreover, they benefited from some communication issues shown by the opponent, as the third goal was a great example for that, when Maik Frantz and Marc Torrejón were not in agreement about who should attack Forsberg during a Leipzig counter-attack.

After the half-time break, Streich changed the system as he brought on Janik Haberer replacing Torrejón, with a wide back four on display in the second period. The structure in the early build-up did not seem to work out, though. Hasenhüttl’s players stayed passive and shut down the important zones against typical passing patterns in Freiburg’s 4-2-3-1. If anything, Freiburg had some success playing through the outside lanes, but could not set up even a single shot on target.

Adaptation to Schalke’s build-up structure (3/12/2016)

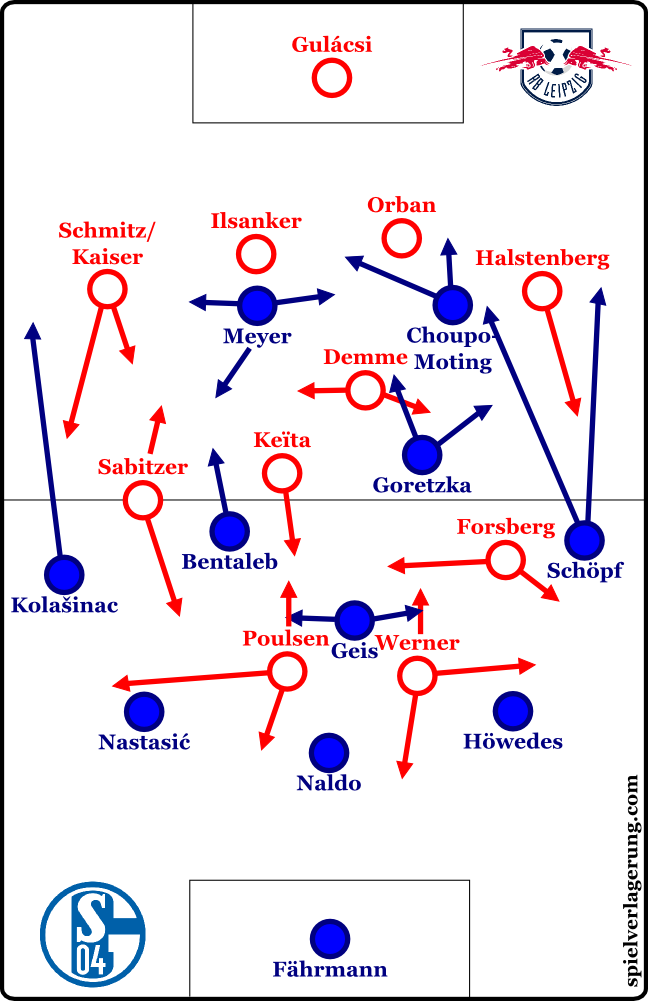

A Saturday evening match against Schalke 04 saw Leipzig once again field their preferred 4-2-2-2. Marcel Sabitzer was positioned a little bit deeper and more centrally than Forsberg. Werner’s initial forward run was supposed to push Schalke’s build-up to the right side. Both Leipzig strikers tried to keep Schalke off the centre. For that purpose, they started their runs close to Schalke’s no. 6 Johannes Geis coming from an angle towards Schalke’s defenders who were wide, so Leipzig could force the first pass to go to the wing. Moreover, Leipzig’s ball-near winger jumped onto the passing lane to intercept the pass which was meant to reach the wing-back.

There were also phases during the match in which Leipzig employed a rather passive 4-2-4(-0) that benefited from the fact that Schalke’s midfield line was a couple of yards too far away from the deepest line, which allowed Leipzig’s first pressing line to cut the connection. The tactical trigger in that case was the body position of Benedikt Höwedes. As soon as the German international turned towards the touchline, Werner ran at him at high speed.

There were also phases during the match in which Leipzig employed a rather passive 4-2-4(-0) that benefited from the fact that Schalke’s midfield line was a couple of yards too far away from the deepest line, which allowed Leipzig’s first pressing line to cut the connection. The tactical trigger in that case was the body position of Benedikt Höwedes. As soon as the German international turned towards the touchline, Werner ran at him at high speed.

The match against Schalke made clear that the principle of outnumbering the opponent in relevant zones cannot only be effective against teams with weaker technicians, but also against a top-class XI such as Schalke’s. Thanks to the high degree of compactness when blocking passing lanes Hasenhüttl’s players had several interceptions right in front of the opposing build-up players. Following those turnovers, the likes of Werner and Sabitzer made explosive runs into the centre and the holes in order to occupy the vertical lanes and allow direct passing combinations behind the opposing back line. All in all, an extremely high horizontal compactness with flexible 4-2-2-2 structures could set up counterpressing and quick layoff passes in transition attacks.

Being 1-2 behind following a Sead Kolašinac own goal two minutes after the half-time break, Schalke started controlling the long balls better and partly changed the momentum of the match. The Westphalians capitalised from the open zones next to Leipzig’s centre-midfielders and used more and more long balls with the intention of circumventing Leipzig’s well-organised pressing. As a result, the match became rather wild including many aerial duels and consistent forward runs at both ends of the field. Leipzig had a few longer spells of possession, though their best goal-scoring opportunities arose from transition attacks where the compactness in the middle coupled with dynamic runs behind the line produced breakthroughs.

Effective build-up play against passive Berliners (17/12/2016)

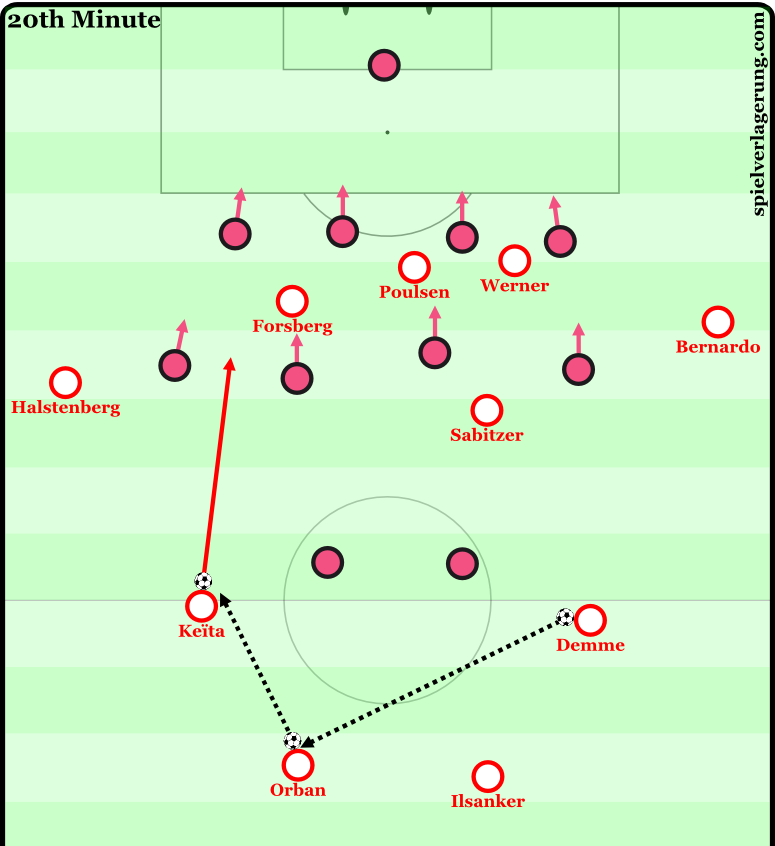

One week after losing against FC Ingolstadt, their first loss in the Bundesliga, Leipzig had the chance to bounce back, displaying a dominant performance against Hertha BSC where the Roten Bullen primarily showed their strength in build-up plays. Hasenhüttl’s side usually started their plays with short-range passing combinations to bypass Hertha’s first line in a typical 4-4-2. Moreover, one of the Leipzig defenders occasionally played a few long balls to Poulsen who normally stood close to Hertha’s right-sided centre-back Jens Hegeler. Build-up passes towards the full-backs, however, were not promising at first, as both Marcel Halstenberg and Bernardo were immediately pressured and had no passing options, because the Leipzig players in the middle were either in the cover shadows or man-marked.

As time went on, Leipzig’s attacking plays became increasingly dangerous. And Hasenhüttl’s players did not even show their usual passing patters—namely long balls into the half-spaces. Instead, the Saxons moved the ball via ground passes through the half-spaces. The Berliners, for the most part, defended in a ‘flat’ 4-4-0-2 where both lines of four dropped back quickly and stood at or in the penalty area. That became particularly obvious prior to Leipzig’s go-ahead goal. After a cross pass to Sabitzer who was on the right side, the Austria international played the ball to Demme, who at the edge of the box could receive that pass without feeling any pressure, as Hertha were in what can only be described as a 7-2-1 shape.

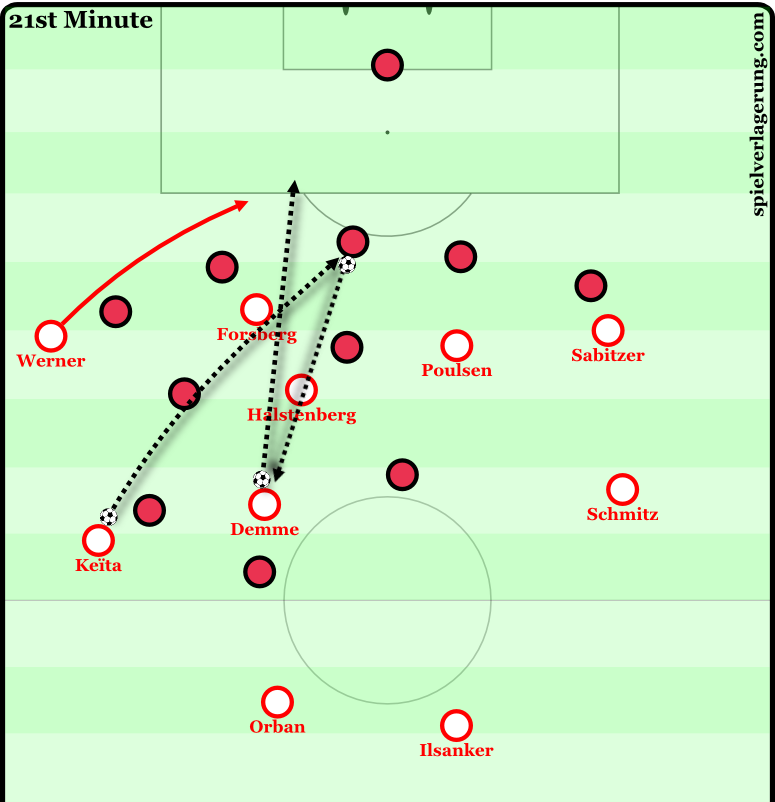

Both opposing centre-forwards, Julian Schieber and Vedad Ibišević, were outnumbered by Leipzig’s centre-backs and centre-midfielders in the first phase of the Leipzig build-up. Demme and Keïta positioned themselves next to Hertha’s first block, as long as Forsberg did not drop back through the left half-space. Both centre-midfielders either passed the ball to each other or they let the ball run through one of the centre-backs in order to evade Hertha’s block. Because of the narrow positioning of the two Berlin strikers and the deep position of the other eight outfield players, Keïta could easily dribble through the half-space and make a run up to the penalty area without encountering any resistance.

The pressing trap sprang. By attacking from an angle, Poulsen forced the pass into the middle where Keïta in a 4 vs 1 could intercept the ball. Leipzig often exploited Hertha’s weak attacking structure.

Also noticeable was the high precision both Leipzig midfielders showed in their passing game. A number of times they played through small gaps right into the feet of Poulsen or Werner who were closely behind Hertha’s two centre-midfielders, which meant that even an inch of inaccuracy would have led to an interception. The same was observable when Keïta and co. displayed quick transition passes made possible by the once again effective pressing. Defensively, two aspects were impressive.

1) Poulsen or Werner repeatedly attacked goalkeeper Rune Jarstein, allowing the Norwegian no time to screen the field before he had to knock the ball into the second third. Following those long balls—sometimes played by one of the centre-backs—Leipzig had aerial superiority in midfield which alleviated the impact of those passes and allowed them to regain ball possession.

2) In phases of pressing, both Poulsen and Werner stood close to each other right next to the second Hertha midfielder who remained in front of the back line as opposed to the one who frequently dropped between the centre-backs. Then Leipzig’s ball-near forward made a curved run towards the widely positioned centre-back who had received or was about to receive the ball. Meanwhile, the ball-near Hertha full-back was man-marked tightly, which left only the passing lanes to the middle open—a part of the plan. Demme and Keïta cut the connection to Schieber and Ibišević and attacked the lone midfielder if necessary. Leipzig exploited the gap in Hertha’s formation masterfully and won the ball repeatedly in order to start transition attacks through the middle.

Once again, Hasenhüttl’s players were successful in all four phases of a football match.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen