Beyond the business model: RB Leipzig’s football philosophy

When a bull is furiously running through the prairie, the earth is shaking. The fauna is on the alert. Everyone knows that a bull is an unstoppable force of nature once he has picked up pace. It is not surprising that a team associated with the image of that animal tries to emulate the bull’s fierceness. It is not surprising that a team with the ambition to become the next big player in German football tries to establish a catchy identity.

Said team is RB Leipzig which has been drawing attention from a wider public ever since it started out in the fifth division in 2009. Backed by the energy drink company Red Bull, it was clear from the beginning that Leipzig would not want to waste any time in old, run-down stadiums out in the sticks. The limelight is what Red Bull part-owner and public face Dietrich Mateschitz and his company are looking for. Just keep in mind the commitments they have made in racing and extreme sports. Red Bull intends to sell a hip product to energised, career-driven people in their mid-20s to mid-40s.

Considering the social structure of an average football crowd it is quite interesting that Red Bull made the step and entered the world of football. Their adventure started by acquiring Austria Salzburg that has won several domestic titles, yet has not been and most likely will never be able to compete on a European level. Thanks to the unattractiveness of Austria’s league, only has-beens with some name value and relatively unknown players who could not make the breakthrough at bigger clubs signed for Salzburg throughout their heyday.

That said, Red Bull Salzburg—as opposed to Germany in Austria it is allowed to put a company’s name into the name of the club—was able to make some waves when Roger Schmidt was in charge as head coach. The former Paderborn player introduced a specific high-energy style of football about the same time when Borussia Dortmund ran roughshod over the German league and several top-tier teams from all around Europe. Even though Salzburg back then did not exactly rely on the same mechanisms as Dortmund, in a bigger picture both head coaches Schmidt and Jürgen Klopp were at the forefront of what can be called the Gegenpressing revolution. Granted, Gegenpressing was not invented in the late 2000s or early 2010s, though the conscious use of pressing traps and trigger mechanisms to force transition attacks was certainly an aspect that had rarely appeared in that specific form.

Schmidt’s stint at Red Bull Salzburg lasted from 2012 to 2014. At that time, RB Leipzig were getting promoted twice—from the fourth to the third German division in 2013, and from the third to 2. Bundesliga in 2014. The key figure in all of this was and still is Ralf Rangnick, who not only has been serving as sporting director at RB Leipzig since 2012, but who also was the sporting director of Red Bull Salzburg between 2012 and 2015. Under his supervision, Schmidt built up Salzburg as said Gegenpressing powerhouse. Under his supervision, head coach Alexander Zorniger failed to advance Leipzig in the Saxons’ first season in the second Bundesliga. That was when Rangnick decided to take matters into his own hands. The former Schalke and Hoffenheim coach returned to the sideline and guided Leipzig into the top flight of German football.

Partially inappropriate approach last year

Interestingly yet unsurprisingly, Rangnick’s system resembled a lot of elements his former employee utilised in Salzburg and has been continuing to utilise at Bayer Leverkusen. That meant Leipzig first and foremost relied on a 4-4-2/4-2-2-2 formation with two outside-in wingers and, most of the time, one auxiliary striker as a connecting piece between midfield and the players upfront. Although the 4-4-2 has many known weaknesses such as a rather simplistic offensive structure and a lack of naturally emerging triangles in possession phases, the formation helped Leipzig to make use of four pressing players upfront and basically shut down all passing options the opponents might have had in the early stages of their build-up plays against teams not named RB Leipzig.

However, that strategy had a notable twist, as Rangnick’s team exposed several zones behind their first line. Leipzig’s back line usually dropped behind the halfway line in order to mark opposing strikers which created a significant gap in which the two centre-midfielders looked like they were in no-man’s-land. Clubs such as Gertjan Verbeek’s VfL Bochum capitalised from those apparent weaknesses, yet that did not automatically mean they beat Leipzig. In fact, the Roten Bullen were defensively vulnerable, but so talented offensively that a lost tactical battle did not necessarily result in defeat. Particularly in matches in which Leipzig got the upper hand early on, Rangnick’s players were great at identifying the openings more offensive-minded opponents were giving and took advantage of it. In the manner of a typical pressing team, Leipzig were often desperately waiting for the other team to leave their mouse hole and vertically stretch the effective playing field.

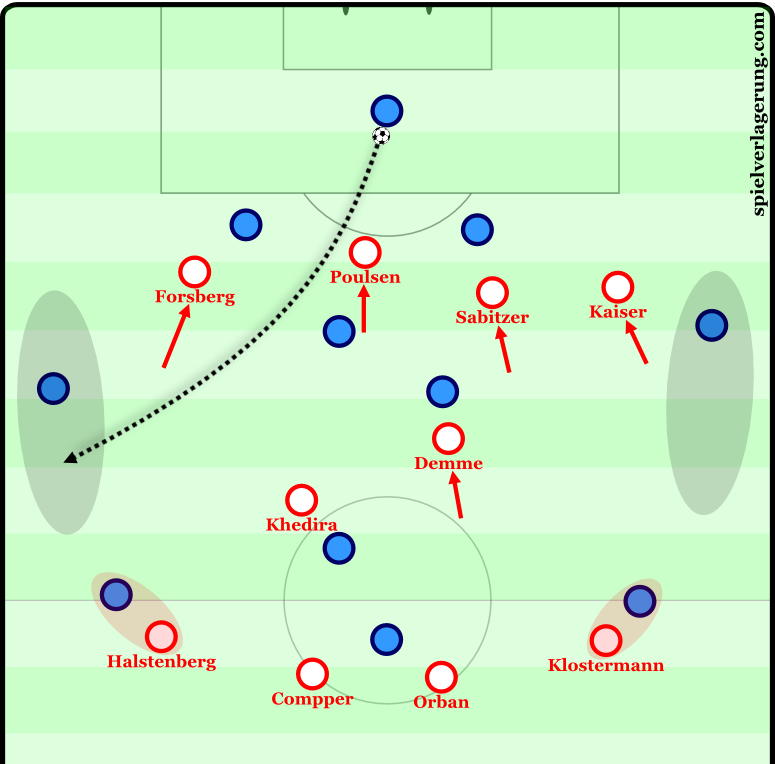

A typical pressing pattern last season, here during the match against Bochum. Due to the man-oriented scheme at the back and slightly hasty forward movement upfront, both wings were quickly exposed.

Despite being an up-and-coming team at first, the vast majority of opponents in the 2. Bundesliga viewed themselves as the clear underdog in encounters with the financial powerhouse. RB Leipzig’s background turned into a slight burden on the field, as they simply could not play up the fact that they actually were the newcomers. Taking away the advantage of being the underdog and therefore the reactive part of a match called their overall approach into question. To some extent, Leipzig were able to bank on their strength in terms of pressing and transition, though they often enough outplayed teams due to the fact that the better, more talented men wore their jerseys. Keeping that phase of Leipzig’s general development in mind makes the transition to first league football even more interesting.

Hasenhüttl puts his stamp on Leipzig

The fact that RB Leipzig would become a force to be reckoned with in the Bundesliga is hardly surprising. But how fast the newly signed coach Ralph Hasenhüttl and his players adjusted to the requirements in Germany’s top flight is astonishing. Above all, the signing of Hasenhüttl himself was the smartest move possible after it became clear that Rangnick would not continue in a coaching position following Leipzig’s promotion.

Hasenhüttl, a former Austria international, made a name for himself turning FC Ingolstadt into a pressing powerhouse with a specific tendency to initiate counterpressing by playing long ball towards the front line. Moreover, in comparison to RB Leipzig’s system prior to the arrival of Hasenhüttl, the 2015-16 Ingolstadt team was far more versatile and adjustable in pressing phases. Although Hasenhüttl has not implemented the 4-3-3 formation he employed at Ingolstadt, he has made several changes in order to increase the level of flexibility of Leipzig’s system.

In particular, these changes have led to a more controlled strategy to set up turnovers. Still, Leipzig usually pressure opponents early on in the build-up phases. It is not a blind chase for the ball anymore, but a more dynamic pressing trap between the first and second lines. For that matter, runs to lead the opposing build-up in a certain direction, appropriate pressing triggers and clear focal points are essential. These aspects are the foundation for specific adjustments to opponents within the confines of the preferred 4-2-2-2 layout.

That said, it would be foolish to narrow Leipzig’s success down to their defensive strength. The Saxons, moreover, deliver a consistent ball-circulation through their deepest line and, therefore, are resistant against customary pressing schemes. Having integrated top prospect Naby Keïta into their system fairly quickly and a once again surprisingly well acclimated Diego Demme as his side kick in midfield, Leipzig possess the individual quality in the middle of the park to bypass opposing midfield lines via dribbles or through quick combination plays. On top of that, the aggressive half-space penetrator Emil Forsberg, accompanied by Keïta, assists Leipzig’s three lightning-fast strikers in Marcel Sabitzer, Yussuf Poulsen and Timo Werner effectively.

As opposed to typical teams that are promoted to the Bundesliga, Leipzig already have a squad that can easily keep up with ambitious top 6 sides. Only the two kingpins of the league, Bayern and Dortmund, clearly overmatch Leipzig on paper. Although a high transfer budget could dupe a front office into buying players based on name value, the Saxons are striking example how a system can be honed by adding the right players to the roster. Footballers like Keïta and Werner are in strong demand across Europe, yet Leipzig offers the perfect package of ambition, resources and professionality to convince these talents of putting their names under the dotted line of a RBL contract. And as Hasenhüttl can exploit their skills by integrating them in a system that fits them very well, Leipzig are able to increase the value of the likes of Keïta and Werner on the pitch and later on the transfer market.

The signing of Keïta shows also how Leipzig can benefit from the Red Bull network. When he was 19 years old, Keïta moved from FC Istres to Red Bull Salzburg and signed a long-term contract until 2021. After establishing himself in a smaller league, showing the potential that he once could become a world-class midfielder, the move to Leipzig was the next logical step, while he is staying in the family.

To provide somewhat of an overview of their recent transfer activities: last summer, Georg Teigl and Stefan Hierländer, two former bench players, left the club on free transfers. Additionally, Atınç Nukan, Massimo Bruno and Anthony Jung left on loan deals. While both Nukan and Bruno have the potential to play an important role at RB Leipzig in the long run, Jung’s days are probably over, as he lost his spot in the starting XI last year and is on the downside of his career despite his recent success at Ingolstadt. Omer Damari and Nils Quaschner departed on loan deals as well. Both have no future in the jersey of RBL.

On the other side, Leipzig spent 50 million Euro last summer, signing a decent amount of prospects. Both Oliver Burke and Naby Keïta cost 15 million Euro. Timo Werner was signed for a transfer fee of 10 million. Both right-backs Bernardo and Benno Schmitz, who like Keïta moved to Germany from Red Bull Salzburg, were worth six million and 800 thousand, respectively. Substitute goalkeeper Marius Müller had a 1.7-million price tag. Greek defender Kyriakos Papadopoulos came on a loan deal from FC Schalke 04, which required a fee of 1.5 million.

The current roster is certainly talented, but does not leave Hasenhüttl with many options in case a few players are injured. Only 19 outfield players have had realistic chances to make the first XI or the bench in recent months. If the injury bug bites with full force, as it happened in Leipzig’s defensive department, then it can cause some headaches. Marcel Halstenberg is the only reliable left-back, considering youth player Dominik Franke is realistically not ready for Bundesliga. Oliver Burke and Davie Selke are the only alternatives upfront. Even in central midfield the options were fairly limited, especially after Stefan Ilsanker had to replace Marvin Compper in central defence from mid-November onwards.

Only Dominik Kaiser is another solid back-up player in the middle. Papadopoulos and the defensive all-rounder Klostermann continue to be unavailable for quite some time. Long story short, Leipzig are more or less forced to add a few more players to their squad. Given the intensity the Roten Bullen normally show, the energy bars could be low in April and May, despite a medical staff that is top-notch in Germany.

Defence: tricky pressing traps

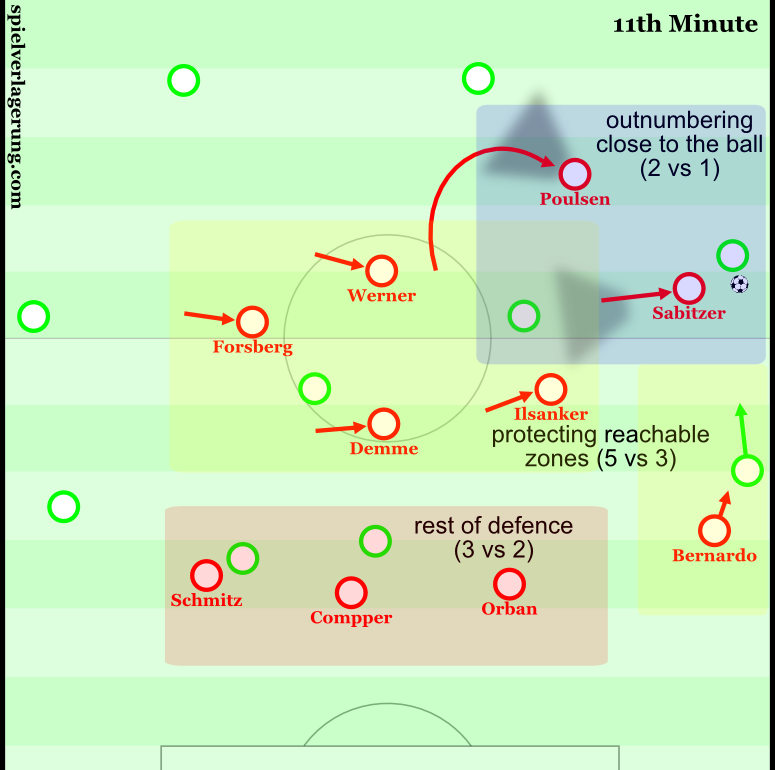

In contrary to the public opinion, Leipzig do, in fact, not go full force in the first phase of pressing. Hasenhüttl has established a balanced structure in which only tactical triggers lead to the application of pressure. At first, both strikers, both centre-midfielders and both wingers circle around the opposing midfielders. If the opponents do not commit any mistakes when building up plays, Leipzig intend to shut down passing lanes by remaining in a compact shape close to the ball and apply diagonal zone coverage in addition. Yet as soon as a centre-back or deep-positioned centre-midfielder reveals through body position and/or viewing direction what he intends to do or the ball circulations happens to be inaccurate, the trap springs.

1) Wolfsburg’s left-sided centre-back controlled the ball. Poulsen, Werner and Sabitzer blocked the passing lanes to the dangerous zones. 2) The pass went wide. Werner started his run and pressured. 3) Sabitzer supported him and they outnumbered the opponent. Forsberg moved inward and the centre-midfielders pushed forward to intercept the pass in the middle.

The two ball-near Leipzig players—one striker and one winger—start their runs to create a 2 vs 1, while the block behind them guards the centre of the pitch, which usually enables them to outnumber the opponents in case the ball bypasses the players upfront. Consequently, Leipzig abandon the ball-far side. The two players near the ball make use of their cover shadows in order to block vertical and horizontal passing lanes. The diagonal one remains open on purpose. A turnover in the middle allows Leipzig to produce an immediate breakthrough by getting the pressing players involved who are already in motion. The opponent cannot switch sides or play through the wing quickly because of the way Leipzig make their runs and the degree of intensity they apply. This leaves only two options: risky dribbles or blindly played long balls.

As described, the first three lines of the 4-2-2-2 shape act as a unit. Granted, the moves towards the wing and the forward movement of the midfielders look like common chain mechanisms. The way the players move and position themselves, however, follows certain group tactical principles which are applicable outside of the chain mechanisms:

- outnumbering near the ball to generate pressure and direct the opposing build-up

- guarding the rest of the pitch to outnumber opponents in zones the ball could be played into

- defending goal-near zones only when superior in numbers

These principles are also applicable when the opponent can maintain ball possession after the first phase of pressing.

If the opposing ball-carrier is able to bypass the cover shadow of Leipzig’s winger, the full-back behind pushes forward. The ball-near midfielders move towards the sideline to create double coverage and shut down the passing lane into the centre. The remaining defenders at the back move sideways and secure the offside line. The winger who had been outplayed remains active and closely watches the backwards routes the opposing ball-carrier might consider to use.

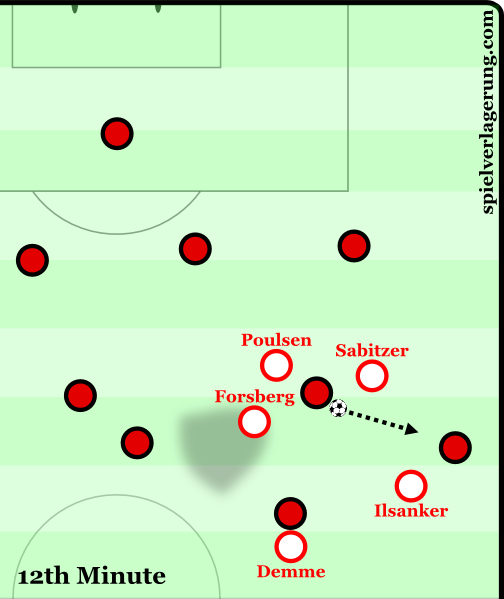

After turning the ball over due to a bad touch, Forsberg rushed from one half-space to the other, despite Leipzig being 2 vs 1 near the ball. The Swede, therefore, exposed the passing lane to the ‘third man’ in the middle.

Only on some occasions, the centre-midfielders are not quick enough to close down the zones they are assigned to cover, as explained above. This sometimes enables the opponents to move the ball into the space between the lines. In this case, Leipzig’s chains would narrow the space extremely. A term for this kind of defensive mechanism is Raumfressen (scoffing space). One of the defenders at the back leaves his initial position and makes a move forward, while his colleagues at the black guard the space in front of the goal. The midfield line circles around the ball-carrier and attacks the ball aggressively. It allows Leipzig to avoid that the opponent have more than one successful action in between the lines of the Roten Bullen. Because of the pressing triggers and a high degree of compactness caused by the explained principles, Leipzig are the only team in the league with an amount of pressing actions and blocked shots above the league average.

The Raumfressen is applicable in wild scenes including quick changes of ball possession and many duels as well. In these cases, the Roten Bullen occasionally overreact and move with too many players into the ball-near zones. This turns into a problem when these wild scenes happen in spaces at the sideline, as then the protection of ball-far half-spaces or even the centre is abandoned. Admittedly, in most cases the extreme intensity Leipzig display can avoid that the holes get too big, yet against opponents who are resistant against high-intensity pressing it poses a risk to Leipzig. In the match again Bayern a situation like that led to the first goal.

Offense: more than just hoofing

Under Hasenhüttl’s guidance, Leipzig have learned to start fast attacking plays out of a slow ball- circulation from a back three. The mechanisms in the build-up are similar to those in attacking transitions. Often enough, Leipzig even play the ball backwards after a turnover to use the following processes contrary to the natural dynamic of the moment.

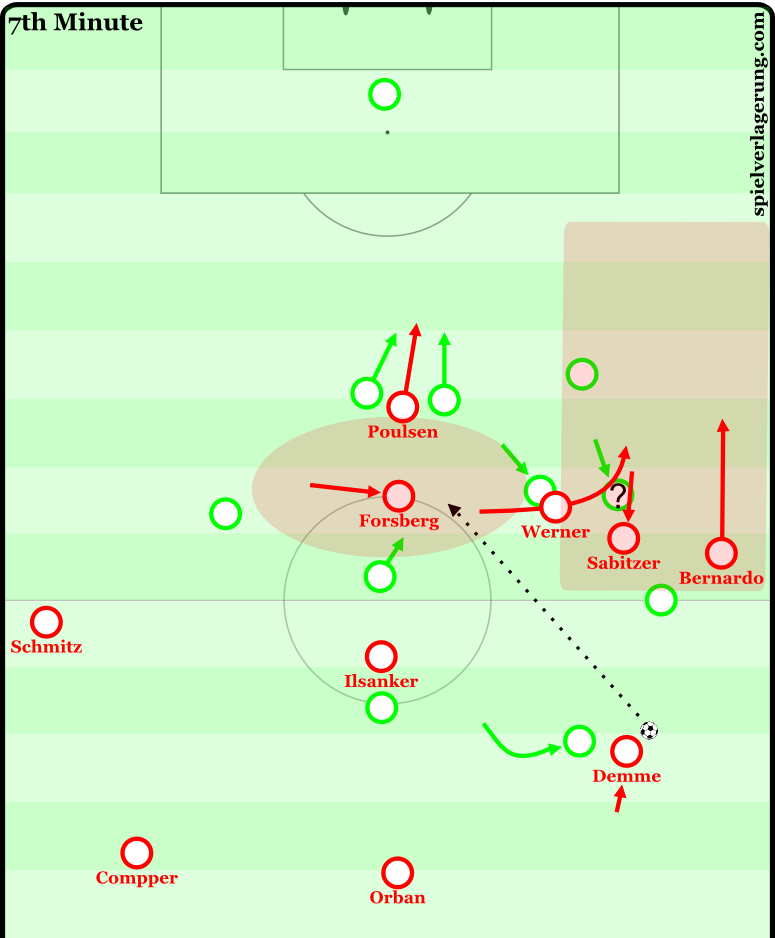

To allow a rather calm ball-circulation, Leipzig want to outnumber the opponent at the back. Against a lone centre-forward, goalkeeper Péter Gulácsi gets involved, thus the two centre-backs can be connected even when the opposing strikers is positioned between them. Against two centre-forwards, either one full-back remains in a deep position or Demme drops back diagonally. While letting the ball circulate, the attacking players go through specific switching motions to open up holes and be at a speed advantage when making runs behind the opposing back line. Especially forward moves by one of the defenders through the half-spaces are normally signs that Leipzig will accelerate in the next moment. Most of the time, the two centre-forwards drop back or leave the centre, which lets the wingers push into the middle and allows them to make deep runs. If it is possible, a so-called laser pass (driving ground pass) to Forsberg or to one striker who returns from the wing to the middle is the first option. One pass can fool several opponents and set up consecutive actions using the natural dynamic upfront.

Opening and utilising spaces explainend based on a scene against Wolfsburg: Poulsen went behind the line and opened the zone between the lines. Sabitzer dropped back and pulled the right-back off the back line. Werner attacked the open space on the wing and created even more room for Forsberg. Demme feinted a long ball, but played a laser pass to Forsberg instead. The Swede could not control the ball perfectly, though. Arnold’s backwards pressing was decent damage control.

The focus on getting to the offside line quickly does not cause negligence of the midfield as many teams with similar tactical approaches tend to do. Quite the opposite, due to the dynamical occupation of the wings high up the pitch, Leipzig can overload the centre with the players who stay in the middle. As Sabitzer moves inwards and Keïta pushes forward, coupled with the dynamic movement of Forsberg, Werner or Poulsen, Leipzig often create a diamond-like 1-2-1, which allows them to pick up the ball if a long vertical pass was not successful the moments prior. Additionally, the two players in both half-spaces, especially Keïta, can dribble a few yards following diagonal passes. Thus Leipzig display great defensive protection and can choose between several options to get closer to the goal line.

Leipzig exploited Wolfsburg’s man-oriented scheme to open big spaces. Because of switching motions a 3-diamond-3 shape was created. Compper could choose between releasing Werner or Bernardo downfield, utilising the great physical presence in the middle by setting up a Poulsen layoff header, or dribbling towards the centre to create a 5 vs 4.

In a follow-up, we will analyse a few matches to illustrate the adaptivity of Leipzig’s pressing system and the progress the team made in terms of build-up play. Our German readers can check out the analysis of RB Leipzig’s Hinrunde written by Tobias Wagner and Constantin Eckner.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

soccer jerseys January 2, 2020 um 9:44 am

Very good