Preview: EURO 2016

Before the EURO tournaments starts, we would like to offer a short preview of all 24 participating teams, including predictions of possible starting line-ups.

Group A

Although the France national team did not have to play a single competitive game since they lost to Germany in the quarter-final match of the 2014 World Cup, the sheer magnitude of talent, plus, to some extent, the home field advantage make the case for France as a title contender.

They showed glimpses of their potential during the tournament in Brazil, yet struggled with some holes in their game. Two years later, the likes of Paul Pogba and Antoine Griezmann have matured even more, so that the axis of Didier Deschamps’ side offers everything a national team needs.

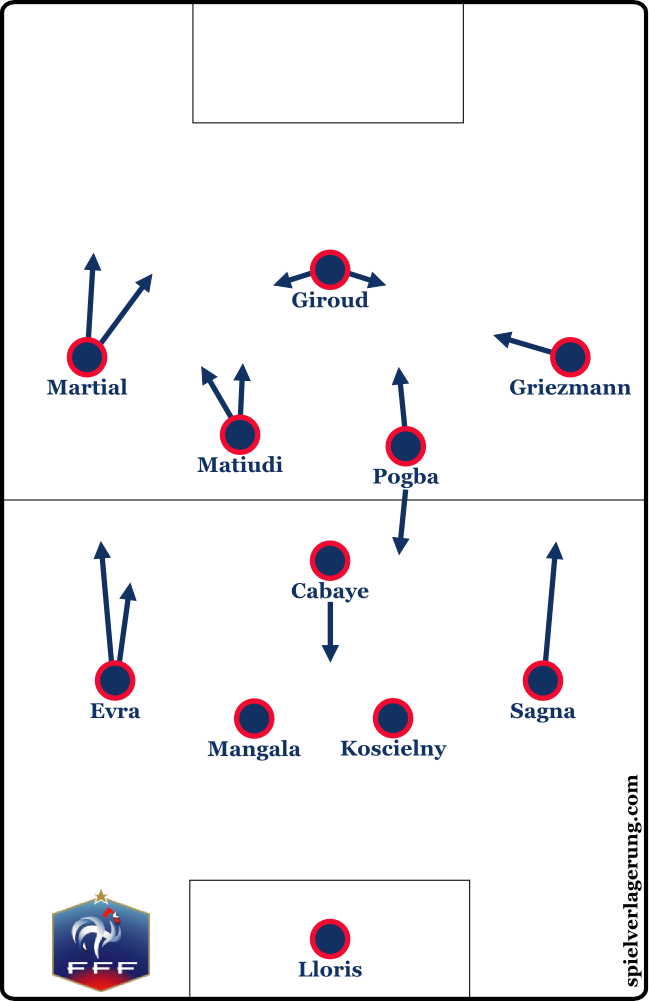

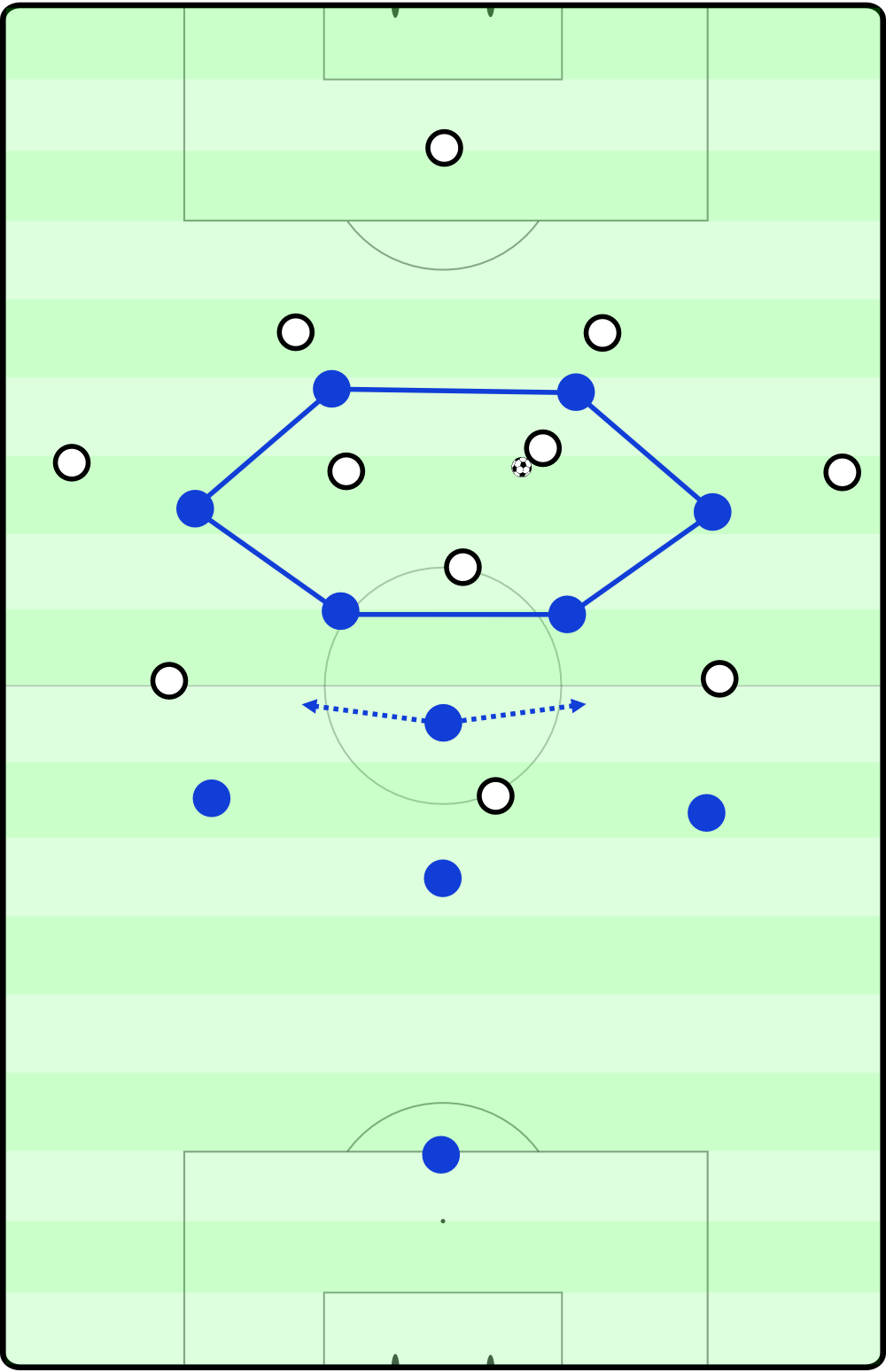

The former Monaco and Juventus coach still sticks to a familiar 4-3-3 shape, featuring Paul Pogba and Blaise Matuidi as two number eight players. As of now, it is not one-hundred percent clear who will back up these two midfield engines.

The former Monaco and Juventus coach still sticks to a familiar 4-3-3 shape, featuring Paul Pogba and Blaise Matuidi as two number eight players. As of now, it is not one-hundred percent clear who will back up these two midfield engines.

Manchester United’s Morgan Schneiderlin with his consistent yet not overwhelming performances could have logically claimed this spot, especially considering the fact that Yohan Cabaye, France’s number six in 2014, left Paris Saint-Germain and joined Crystal Palace last summer. Cabaye offers proper passes and flawless positional play, but the 30-year-old occasionally lacks the dominance Deschamps’ pivot requires. Schneiderlin, however, was snubbed by Deschamps, who instead opted for Leicester midfielder N’Golo Kanté who only made his international debut in March.

Discussing the attack, the Équipe Tricolore have to digest the loss of Karim Benzema due to the scandal involving the Real Madrid striker and winger Mathieu Valbuena. Although Olivier Giroud has often enough proved his critics wrong, a fit and in-form Benzema could have created space for his team-mates like no other striker with a French passport.

Having said that, it is Anthony Martial, an uncut diamond from Manchester United, who could turn France’s talented attack into an unstoppable powerhouse. Deschamps usually fields him as a left-winger, with Antoine Griezmann, another dynamic forward, on the right. But the head coach can mix things up pretty easily.

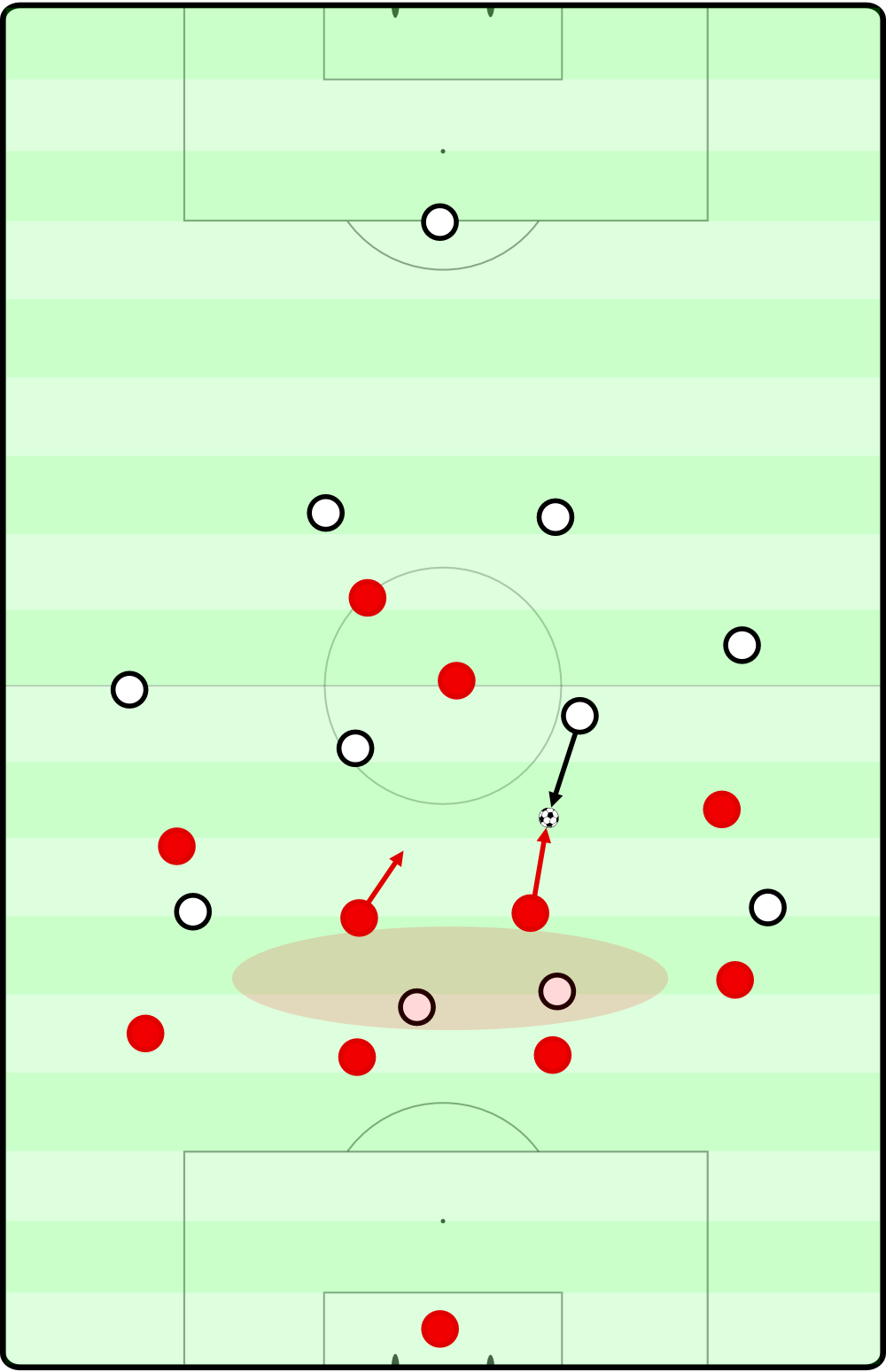

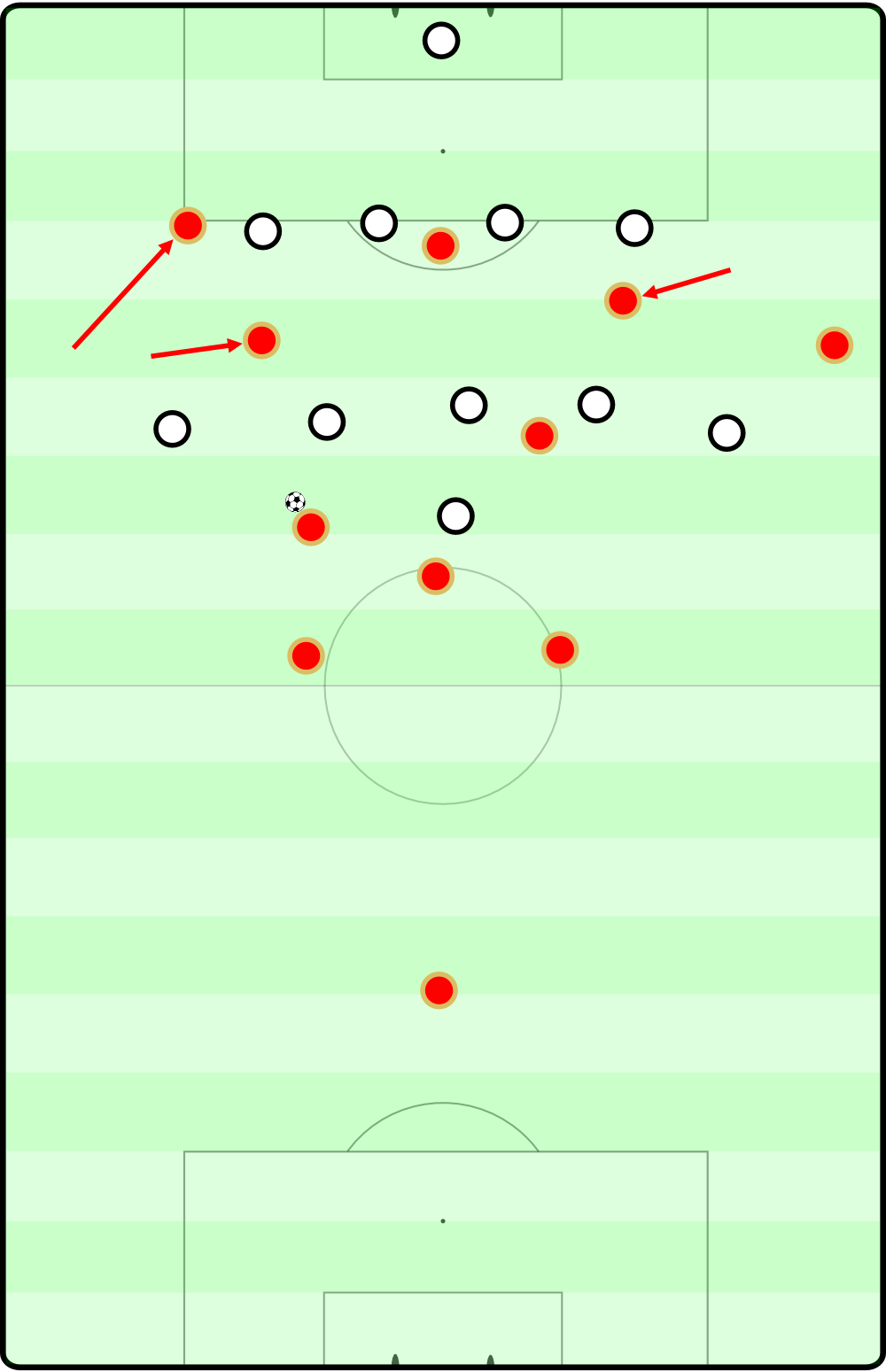

Defensively, a rather open 4-3-3 transforms into a compact 4-1-4-1, as only the centre-forward constantly roams around up front. France prefer zone coverage in the middle and double coverage on the outside, as the wingers are situationally assigned to cover the opposing full-backs, while the full-backs move to the inside to minimise the gaps between them and the central defenders. In case the ball-near winger is positioned relatively deep, the central midfielder next to him moves a few yards forward. Les Bleus understand football as a game of spaces.

They do not use a high press. Even against outmatched opponents, there is no wild ball hunt in the final third of the pitch. Rather, it is a lone striker who is supposed to keep the opposing centre-backs busy, and it is sometimes a compact line of five, shaped like a curve, behind him. Moreover, they rely on the individual quality of the centre-backs when it comes to defending their own penalty box.

Although the likes of Laurent Koscielny, Samuel Umtiti and Eliaquim Mangala are rather quick on their feet and can play an accurate pass to set up attacks, they are unspectacular as far as build-up plays go.

That is why a central midfielder like Kanté could be the right choice, because, at times, he has to drop back and pick up the ball. Alternatively, all three central players keep the triangle very tight, avoiding penetration in the middle. It makes it more difficult to receive the ball, but once they have it, they can initiate quick combos, while protecting each other and having the opportunity to counter-press if they lose the ball.

Overall, France want to keep the ball on the ground, toggling between speeding their attacks up and playing accurate passes in a low rhythm. Both wingers tend to move into half-spaces, even though Martial sometimes forces one-on-ones coming from the outside. In general, the narrow positions of Martial and Griezmann open up the outside lanes, so that playmakers in the middle are able to slide passes into the full-backs’ paths.

There are plenty of patterns you can observe watching games of the French team. The hosts of the 2016 Euros basically put the opponents’ brains in a flurry, as they provide that many options when entering the opposing territory. For instance, Matuidi loves to penetrate the wider area on the left, creating space for a team-mate to move to the inside. These runs – or rather off-the-ball feints – are all about deforming the opponent’s shape.

Last but not least, Paul Pogba, a rising star in European football, was probably too boisterous in 2014, but has become that kind of box-to-box authority the French team use in all phases of the game. While Griezmann is more focused on making breakthroughs near the penalty area, Pogba seems to be ubiquitous. He wanders through the half-space with the determination of a man who conducts the future champions of Europe. The question that remains at this point: How deep have must Pogba and Matuidi sit when France face a top-tier opponent? Will it diminish their ability to pounce on the opponents once they have the ball?

Key element: overloading the opponent’s CPUs by creating plenty of options when stepping on enemy turf

***

France will most likely dominate Group A with ease. Meanwhile, Switzerland could lead the rest of the pack. Coming off an up-and-down performance at the 2014 World Cup, the Nati came in in second place in their qualification group, with two losses against unbeaten England and a defeat at Slovenia. Scoring four goals, Stoke City’s Xherdan Shaqiri was their best finisher.

And he is probably more. The 24-year-old, who has carried the burden of being nicknamed “Alpine Messi” – maybe it is true, at least he is the best dribbler in the Alpine region – has seemingly become heart and soul of the Swiss attack. The revival he is experiencing at Stoke could happen at the right time.

And he is probably more. The 24-year-old, who has carried the burden of being nicknamed “Alpine Messi” – maybe it is true, at least he is the best dribbler in the Alpine region – has seemingly become heart and soul of the Swiss attack. The revival he is experiencing at Stoke could happen at the right time.

Vladimir Petković, who replaced legendary trench-coat-wearing coach Ottmar Hitzfeld after the World Cup, is in favour of basic structures and clear-cut roles. The Sarajevo-born usually draws up a customary 4-2-3-1 formation on the tactic board, with Shaqiri either playing as winger or as a number ten.

Luckily for Petković, the Swiss team has a couple of versatile attacking players. The likes of Admir Mehmedi and Breel Embolo are able to play different positions, and therefore can move around. Plus, Haris Seferović is the appropriate centre-forward who is mobile enough to react to certain circumstances, being a finisher as well as an accurate lay-off passer. Switch-overs and overloads are key elements of Petković’s tactical system, although he heavily counts on his players’ abilities to improvise.

As the pivots too often disappear in the shadow of the opponent’s first block while building up, it can lead to a tendency of knocking long balls towards the offside line despite not having air supremacy. Moreover, in these situations the passing angles are completely ineffective.

Set to be Switzerland’s pivotal point, Granit Xhaka could be the key – or, at worst, the impediment – for a structured build-up play. His well-known move of dropping back between the centre-backs is a way to outnumber opposing pressing lines, albeit he forces the whole team to be positioned deeper.

It is tough to detect a clear on-the-ball strategy. Though, both full-backs incessantly travel up and down the flanks, offering athleticism and width. That kind of linear movement pushes the attacking wingers to the middle, where they can either overload the number ten’s zone or penetrate the lateral zones up front. The use of half-spaces in a simply designed structure could give them an advantage over other teams.

With that being said, the success of Switzerland should still become a matter of who Petković chooses to play. Just look at the central attacking position in midfield: From a defensively reliable yet offensively pedestrian Blerim Džemaili to a pocket dribbler such as Shaqiri, anything is imaginable. And the selection of players influences Switzerland’s strategic direction even more.

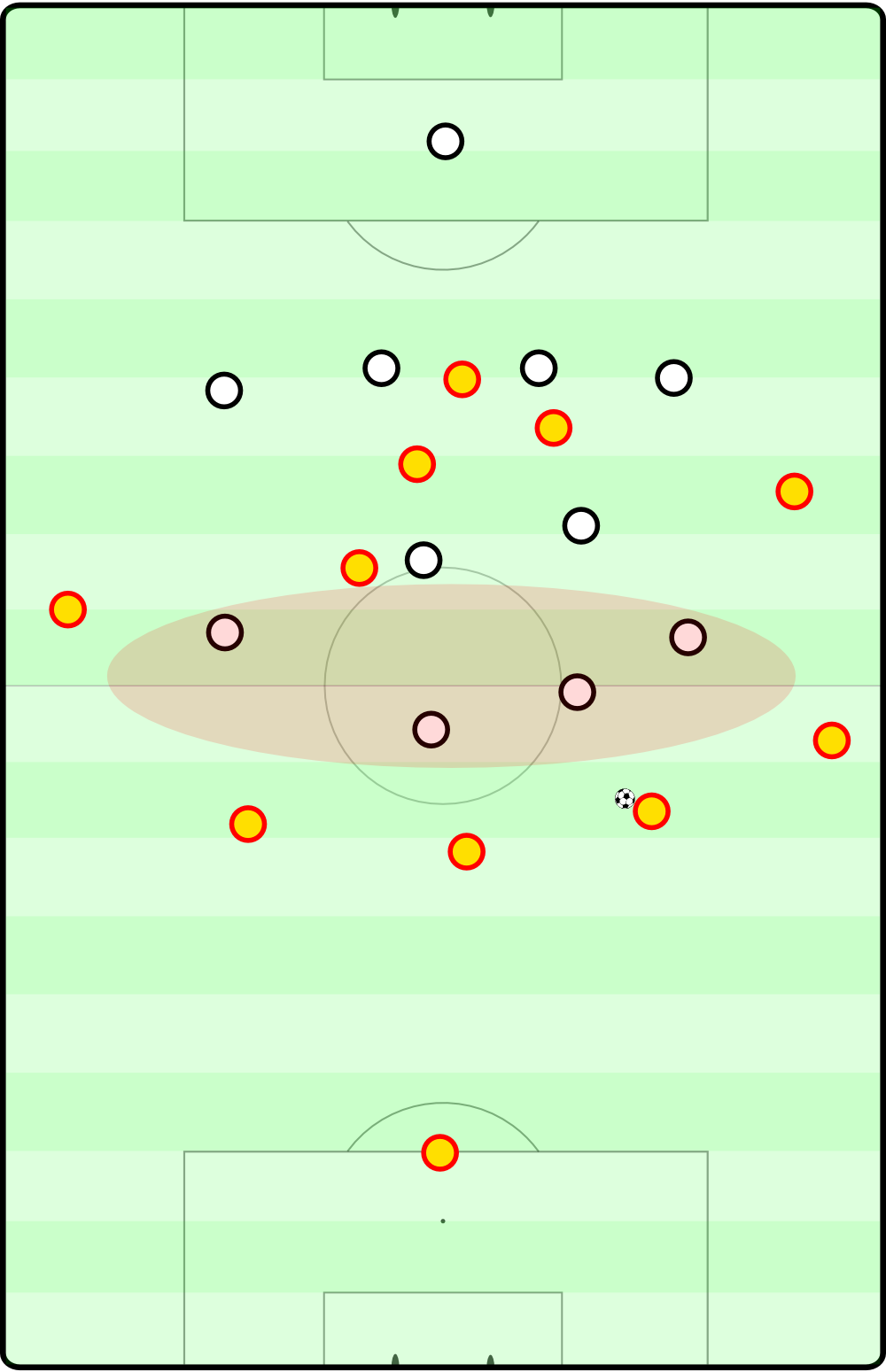

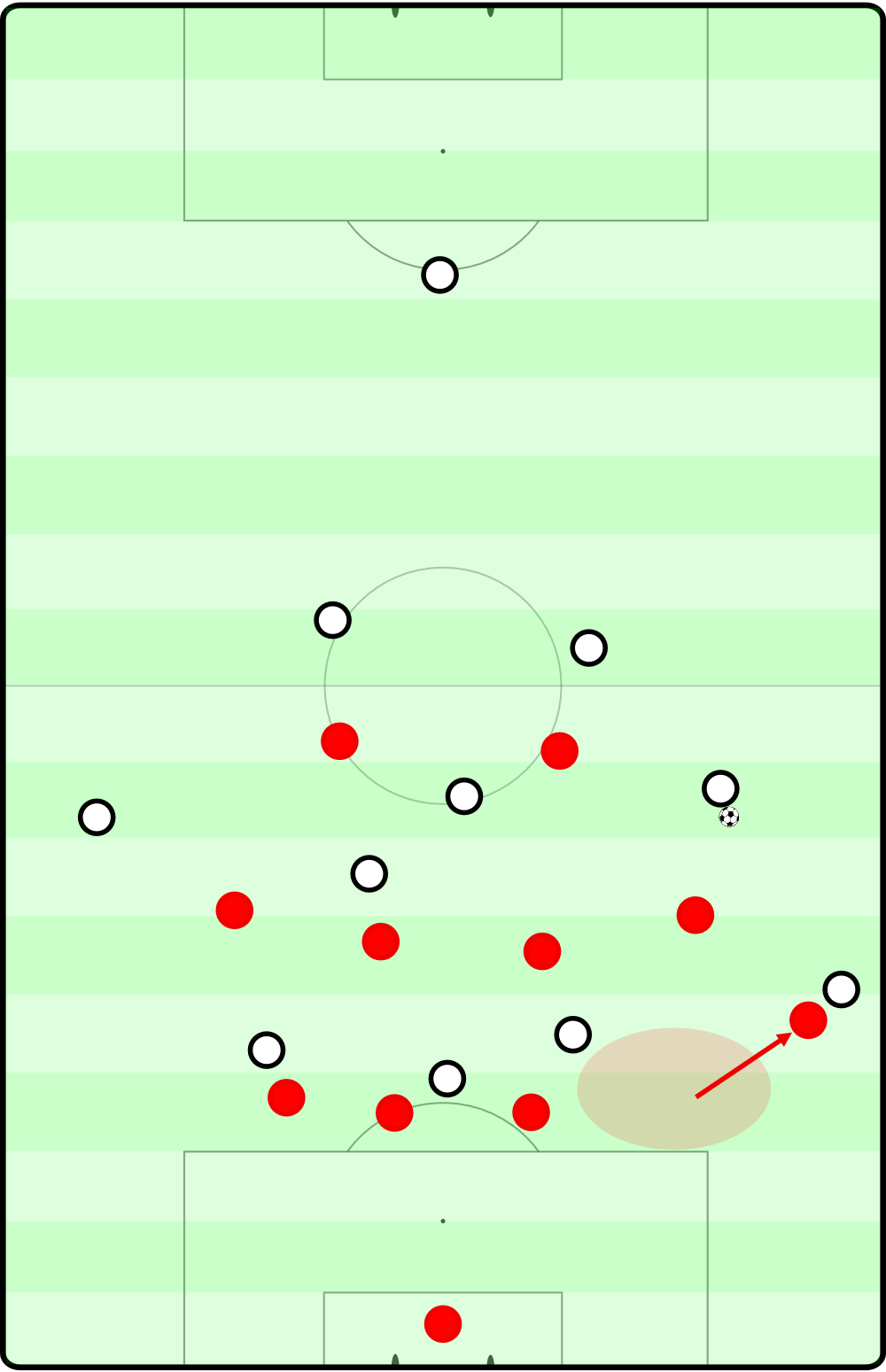

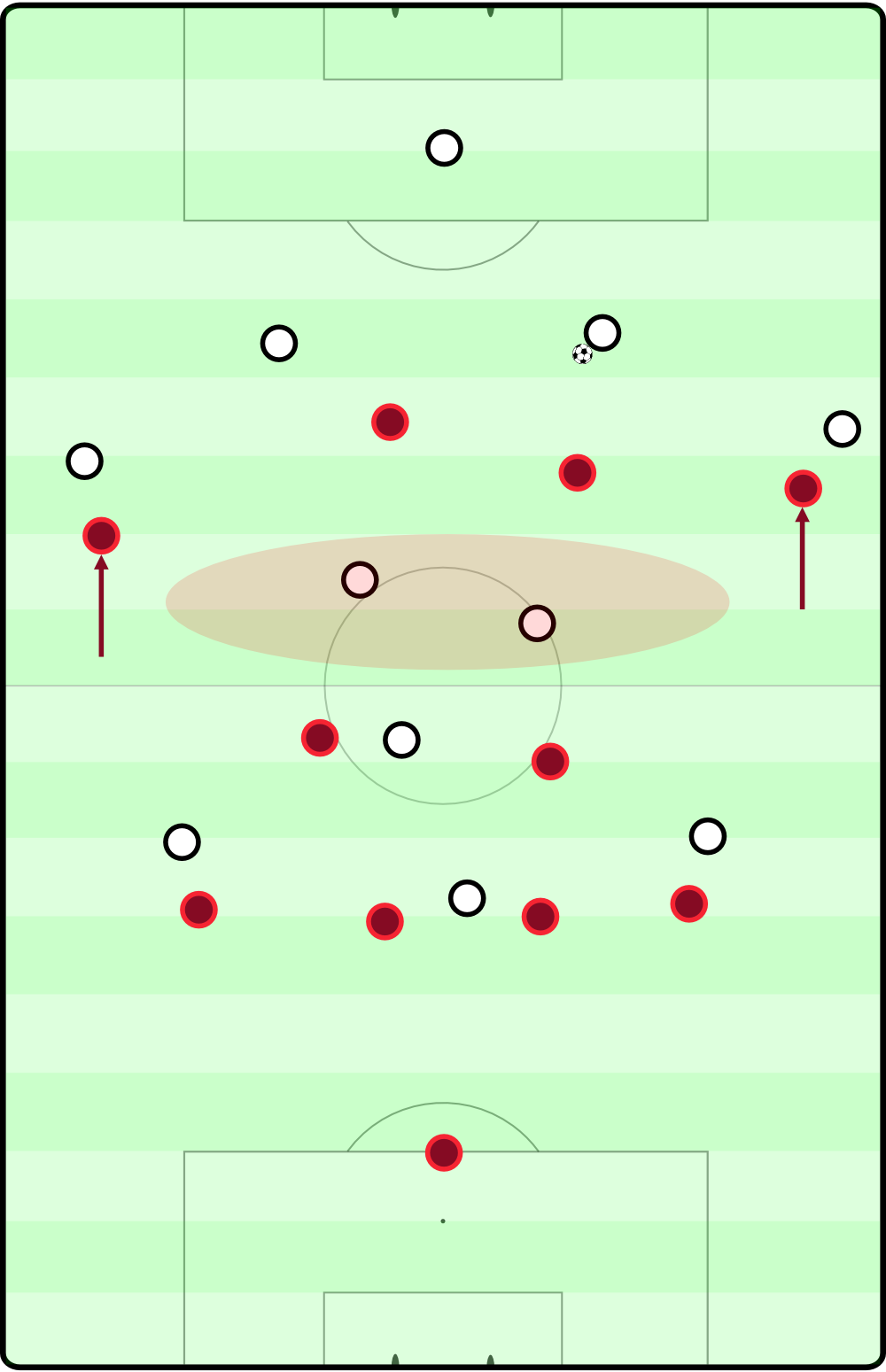

Defensively, the Swiss team do not impose with aggressiveness or the sheer will to recover the ball in a minimum of time. Even against weaker teams, they often utilise a lackadaisical 4-4-1-1 pressing, only intending to cover the own half by throwing enough men into the deeper zones. Despite having this intention, Switzerland’s midfield line gets caught being less compact in the middle.

Providing a remedy, their 4-4-2 pressing looks rather solid. Using this shape, the two players of the first line can attack the opposing centre-backs, moving from the inside out. On the ball-far side, the winger charges forward to maintain a smooth coverage of space.

On the downside, most of their central midfielders behave overly aggressive, while lacking proper positional awareness when it comes to the battle for loose balls. The process of immediate counter-pressing brings out the hunting instinct at the cost of defensive stability. Exposing central zones in front of the back line, these little mistakes could be deciding factors for the outcome of their Euro campaign.

Key element: lack of a distinct game plan, while confiding in collective improvisation

***

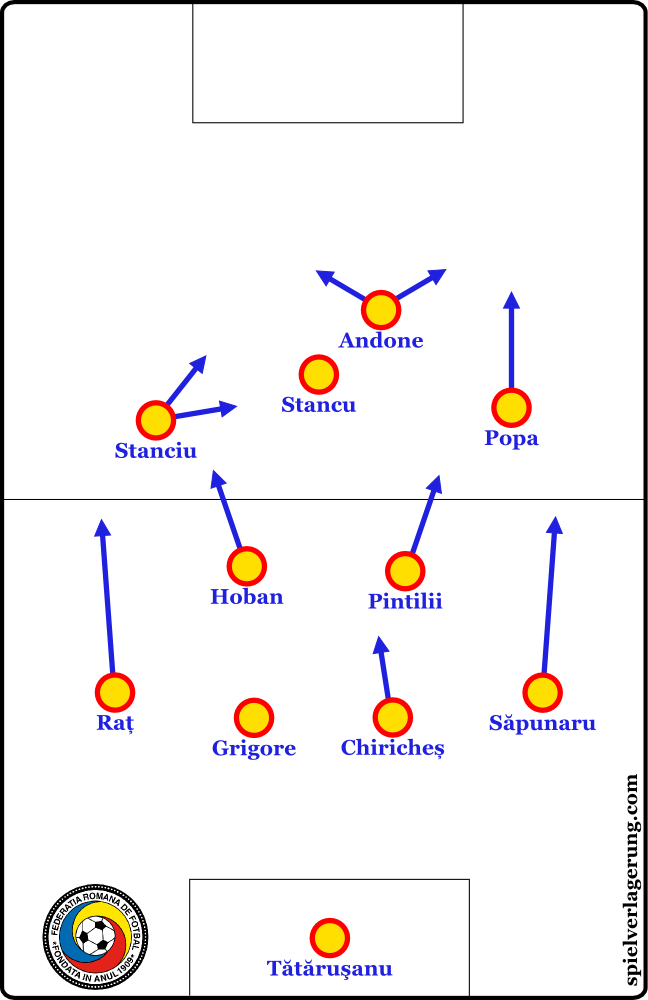

The increase of participants made it possible for teams which have just missed the cut several times to be part of the next Euros. Romania have never been short of high expectations, considering the available pool of talent. Nevertheless, this team will most likely not progress any further than to the round of 16.

Unbeaten in ten qualifying games, Romania had the luck of the draw, as they only had to compete against Northern Ireland, Hungary, Finland, the Faroe Islands and an out-of-sorts team from Greece. Observation in detail leads to the assumption that the Tricolorii are barely able to score against elite defences. After a few wins in the early stages of the qualifiers, Romania struggled to bag goals in 2015.

Unbeaten in ten qualifying games, Romania had the luck of the draw, as they only had to compete against Northern Ireland, Hungary, Finland, the Faroe Islands and an out-of-sorts team from Greece. Observation in detail leads to the assumption that the Tricolorii are barely able to score against elite defences. After a few wins in the early stages of the qualifiers, Romania struggled to bag goals in 2015.

Head coach Anghel Iordănescu is asked to coax anything out of his offense. And the 65-year-old, a former forward at Steaua Bucureşti, almost solely focuses on counter-attacking plays. He came out of retirement to take charge of Romania for the third time in October 2014. Yet, he cannot hide the fact that he is a relic of bygone times.

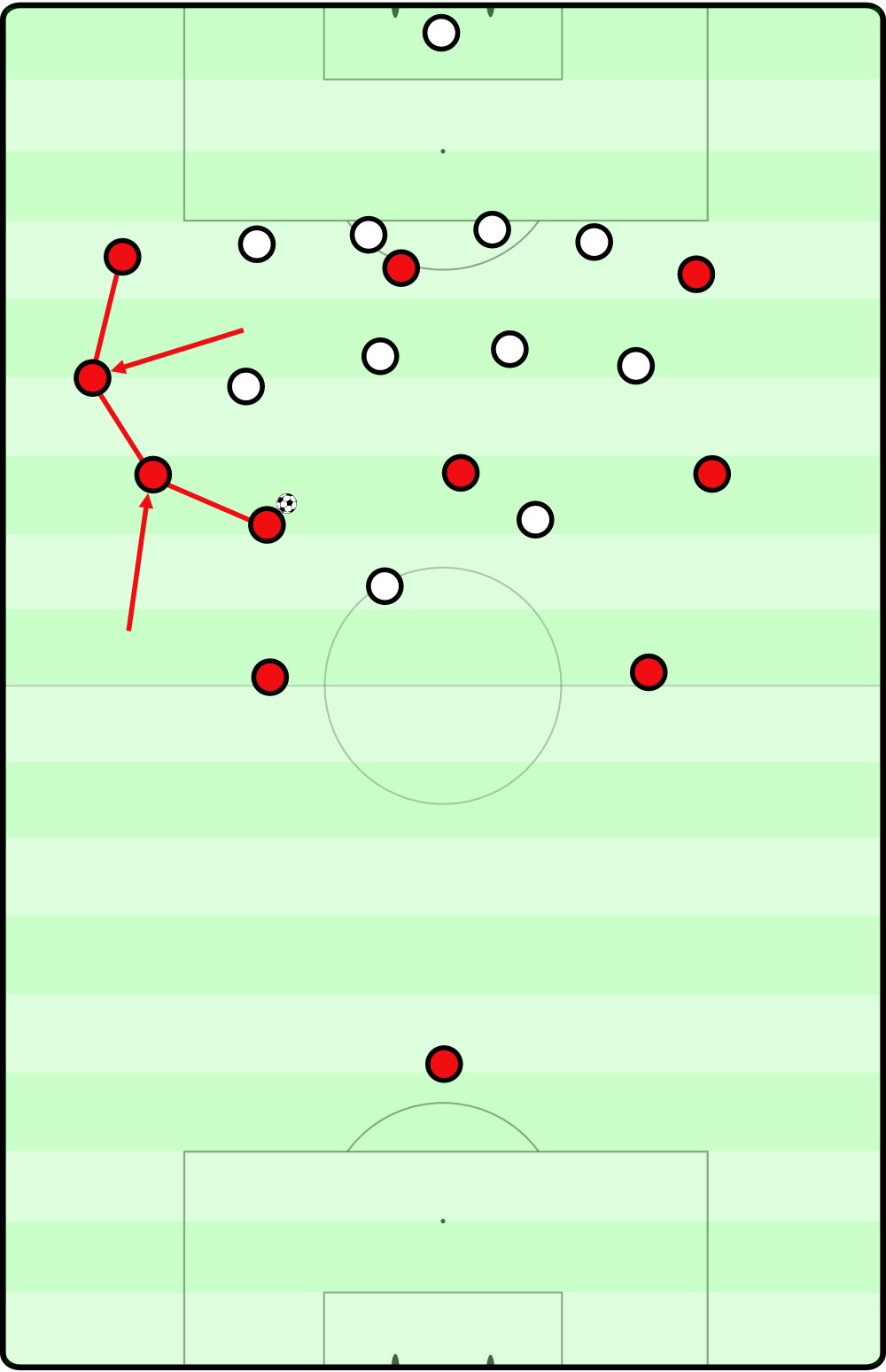

As far as their defence is concerned, a conventional 4-4-1-1/4-4-2 hybrid system normally applies a middle press that is far from intense. The first two players prefer to watch the central passing lanes instead of putting pressure on the ball-carrier. When a Romanian player leaves his position to challenge an opponent, it is noticeable how man-orientated their defensive approach is.

As their attacking output is far from frightening, Romania actually have to keep their lines compact when defending the own half. Unfortunately for them, they very easily loosen their defensive structure, allowing the opponents to enter the negative space between both lines of four.

Occasional isolated challenges – to pressure the ball-carrier from behind, for instance – are their tool to regain possession. Afterwards, a players like Lucian Sânmărtean and Adrian Popa up the tempo, using cuts and diagonal runs to overwhelm the rest of the defence. Iordănescu centres his hopes on this kind of agile player. Without them, there would not even be a discussion about the possibility of scoring a goal at the tournament in France.

Other than overpowering the opponents with counter-attacks, there is little that could raise the hopes of the Romanian fans. They build up attacks with a low rhythm, lacking connections between back line and midfield. Up to six opposing players run through that space. As a consequence, they are often forced to knock the ball forward or to play risky vertical passes.

Even in situations when, for instance, defender Vlad Chiricheș dribbles towards the half-way line, Romania’s passing angles are easy to defend. In longer phases of ball possession, Iordănescu’s side tend to get caught up in the higher outside zones. Logically, Romania put all their eggs in one basket that has counter-attacks written all over it.

Key element: accelerating the pace abruptly when moving forward

***

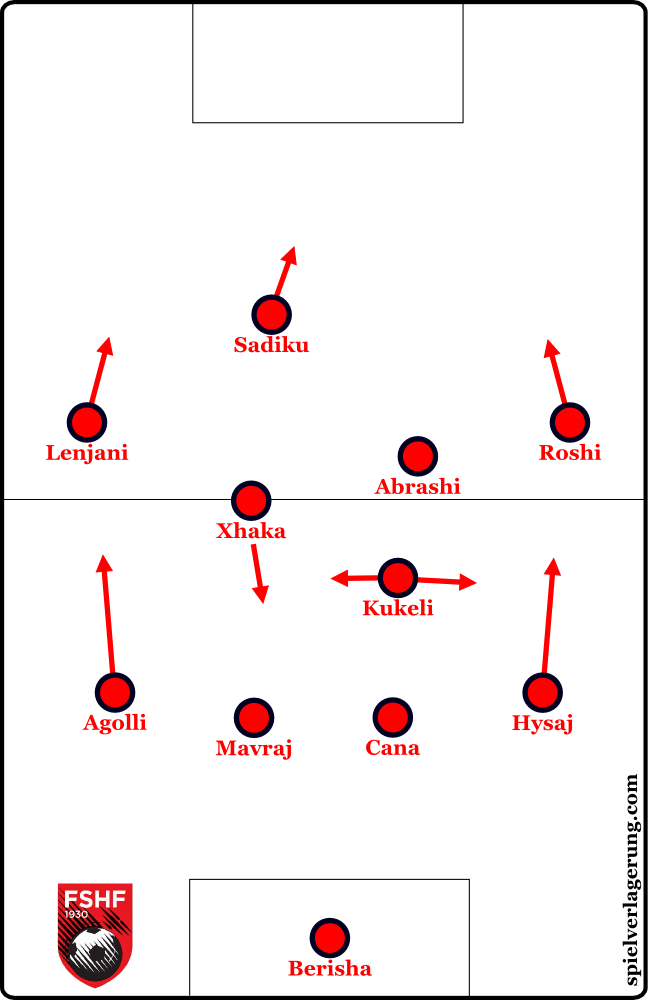

Imagine all the international top players of Albanian descent would actually play for the Albania national team. Imagine Xherdan Shaqiri, Granit Xhaka, Admir Mehmedi, Blerim Džemaili, and Valon Behrami would lace their football boots for this team. Instead, Albania will face them in a match at the Euros – Granit will perhaps even play against his brother Taulant Xhaka.

For the first time in their history, the Kuq e zinjtë passed the qualifiers successfully. But do not expect too much from Gianni De Biasi’s side. The Venetian coached several clubs at home from 1990 onwards, but wanted to leave Italy because he was “disgusted” with the Serie A. He has ended up being Albania’s national coach since 2011.

Of course, the most promising player De Biasi has in his squad is Napoli full-back Elseid Hysaj. Alongside the 22-year-old, experienced players such as Lorik Cana and goalkeeper Etrit Berisha are the axis of a team that features mostly footballers playing abroad.

Of course, the most promising player De Biasi has in his squad is Napoli full-back Elseid Hysaj. Alongside the 22-year-old, experienced players such as Lorik Cana and goalkeeper Etrit Berisha are the axis of a team that features mostly footballers playing abroad.

Like many rank outsiders, Albania often start an attack by playing a long ball, trying to bypass as many opposing players as possible. These balls mostly land in the pockets between Albania’s centre-forward and their advancing midfielders.

Similar to the Romanian team, the hole between back line and midfield line makes it difficult to play short combinations out of the back field. To fix this issue, the midfield block chase back at times, but rather compound the problem, as the team are then positioned very deep.

As such, long balls down the line are seemingly the only way to create quick attempts on target. Cross-passes can be effective when the ball-far winger moves towards the back post, stretching the opponent’s defence. Different types of attacking players coupled with Hysaj’s dynamic and technique could build a dangerous winger pairing on one side.

It comes as no surprise that Albania rely on basic elements in defence. Showing no intention to guide the opponents’ build-up play, their focus is on local compactness. Even if single players leave their position, they are simply too slow, so that the opponents only feel pressure after receiving the ball. Single duels in the middle third can lead to ball recoveries, but as an overall strategy it is inappropriate.

On a positive note, Albania display a surprisingly good formation awareness. Especially when a number eight player rushes forward, turning their shape into a defensive 4-4-2, it prompts a well-working mechanism. A winger moves inwards, while the full-back behind him takes a few steps forward to keep this space covered.

Other than that, it is just as simple as it gets. Defending the own penalty area, which Albania will have to do a lot during the tournament, it is all about planting blocks and making clearances post-haste.

Overall, Albania do at this point not have enough answers in all four phases of the game. And normally, nobody would even bet a penny on them going through to the next round. But maybe it is the right time for another football fairy tale, against all odds.

Key element: blue-collar work ethic

Group B

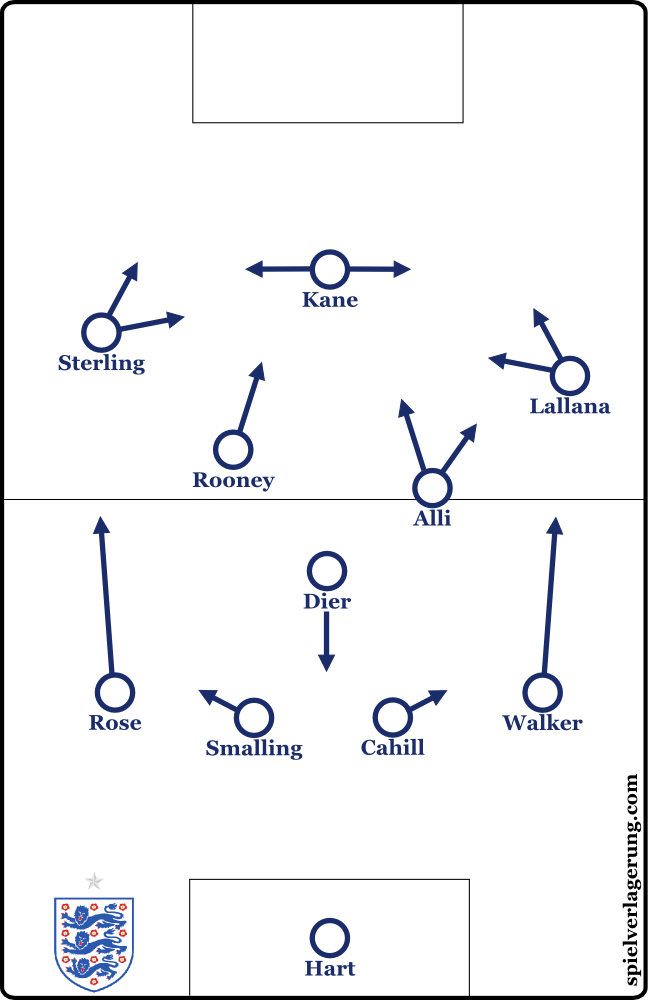

The opinion that the next tournament will be England‘s tournament has never gone away. The motherland of football is facing a hard time as far as their national team is concerned. And head coach Roy Hodgson, once a revolutionary thinker, is every bit an out-dated seniority as his worst critics claim him to be.

Despite having a wide pool full of talents plus some experienced war horses, the English team may lack a clear identity regarding tactics. The Euro qualifiers have given hope, though, as England went unbeaten through their group, gaining wins twice over Switzerland and Slovenia, while only conceding goals against the latter.

Hodgson prefers a 4-3-3 system, with wingers being positioned narrowly in the central zones. As for the personnel, the 68-year-old has the agony of choice, constantly changing his starting XI. Particularly the similar types of players in midfield open up various possibilities, but make it harder for Hodgson to find a perfect combination of players to go with in the tournament.

Hodgson prefers a 4-3-3 system, with wingers being positioned narrowly in the central zones. As for the personnel, the 68-year-old has the agony of choice, constantly changing his starting XI. Particularly the similar types of players in midfield open up various possibilities, but make it harder for Hodgson to find a perfect combination of players to go with in the tournament.

As far as their defence is concerned, England tend to change their formation into a relatively compact 4-5-1 quickly after turnovers, but occasionally deploy a high 4-3-3 press. At times, they try to use their abilities in one-on-ones when it comes to counter-pressing, but the runs resulting from the desire to recover ball possession are mostly wild and man-orientated, so that the opposing team can anticipate England’s next move during the first moments after possession changed.

Once the opponents control the ball and move it forward, England backtrack to close the distance between midfield and back line. It seems more like a hesitant block than an intense counter-press without anticipating opposing passes. Speaking of defensive issues, England’s tendency to constrain one-on-ones has counterproductive effects. Mostly, the English defenders plant themselves in front of the attackers, whereby they look stiff and static, which makes it difficult to defend fluid motions.

In a bigger picture, England’s man-orientated defensive strategy enables the opposing full-backs to decoy the wingers out of their position by standing in deeper wing zones. Therefore, the emerging holes can be occupied by opposing midfielders who run towards the touchline. Generally speaking, Hodgson’s side is vulnerable to quick movement and attackers who switch positions repeatedly. Moreover, winning the ball in unfavourable positions, if at all possible, makes their counter-attacks erratic. Against tough and intensively counter-pressing competition, it is questionable whether England are able to escape condensed zones after winning the ball.

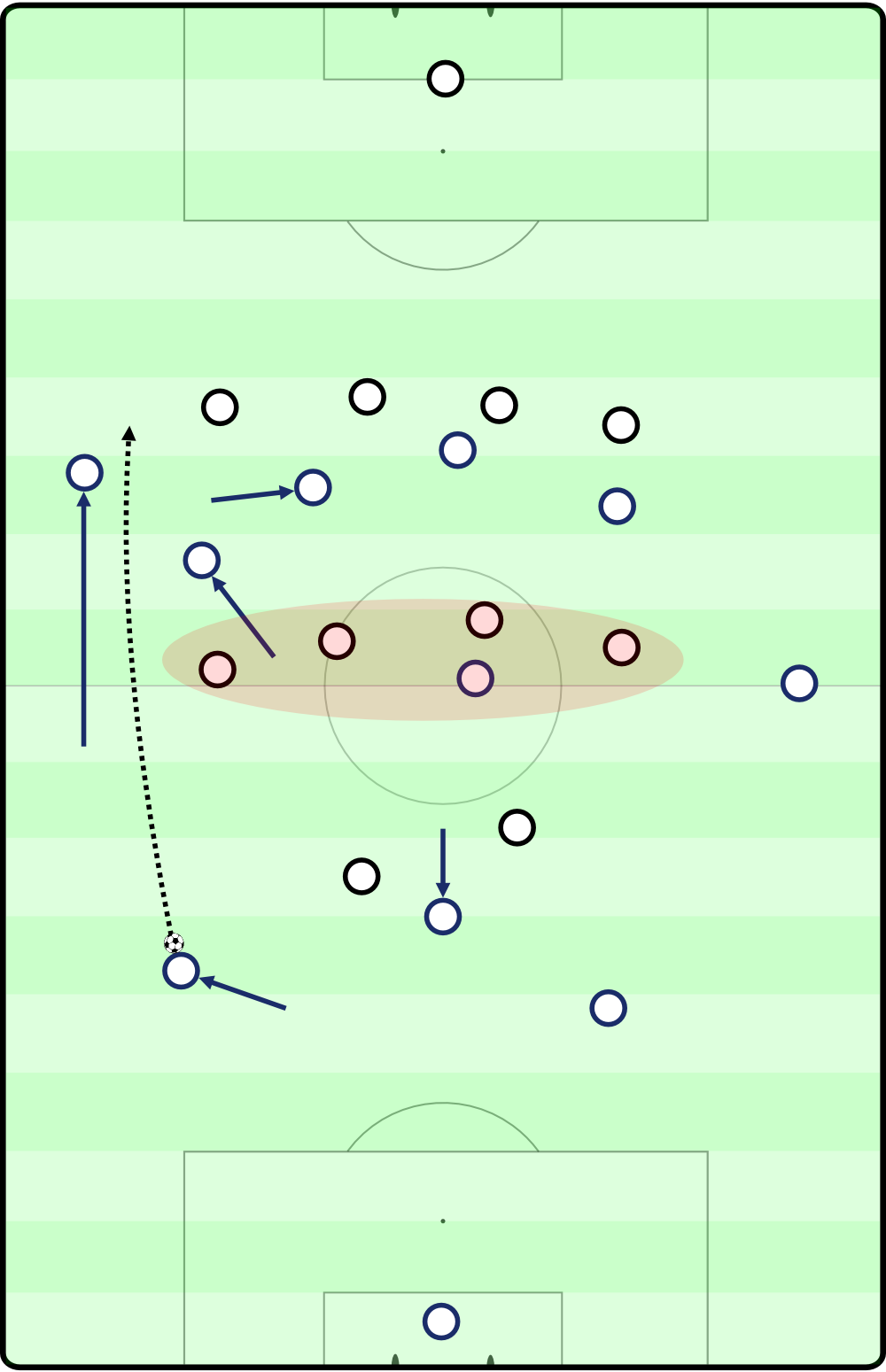

By the time the Three Lions are asked to build up attacking plays out of their back line, we can clearly see a preference towards long balls. The centre-midfielder normally drops back, standing right in front of both centre-backs who tend to split up, moving to wider zones, while the English full-backs are on their way to the offside line. As a consequence, both centre-backs can avoid being blocked by an opposing player and therefore are able to play long passes along the outside line.

In case England’s full-backs attempt to get involved in the initial build-up play, they usually run right into the opponents’ cover shadow, making them unavailable as pass receivers. From time to time a centre-back feels the urge to march forward, yet the lack of help coming from the centre-midfielders, who actually should open gaps, hamper these intended runs.

Another significant element of Hodgson’s side, when in possession, is the movement shown by both number eight players who are usually cut off from the centre-backs and rather overload the wing zones up front to support the advancing full-backs. Plus, they sometimes wait in the upper backfield to receive the ball when a full-back or attacking winger intends to loosen a tight situation near the opposing penalty area.

Both centre-midfielders are also inclined to play longer, diagonal balls from the middle over the top of the opposing back line. Unfortunately, these passing angles are not helpful in terms of maintaining the dynamic of an attacking play.

Overall, England display a rather odd attacking rhythm. Long balls often follow on quick dribbles where the midfielders free themselves of pockets in the middle third. Consequently, the respective ball receiver has to slow down up front, while fighting for a perfect position against opposing defenders. These sequences destroy the flow of England’s attacking plays all too frequently.

They are far more effective by using quick one-twos, involving their technically gifted playmakers and the attacking wingers, whereby the latter are not bound to a certain zone. Rather, they are allowed to roam around, mostly penetrating the space between the opposing lines. Raheem Sterling is also focussed on his dribbling ability which can either be helpful – if he beats opponents with all speed – or it can interrupt the progress of a play.

As an alternative to their 4-3-3 system, Hodgson occasionally uses a 4-2-3-1, with Wayne Rooney as a number ten player behind a centre-forward such as Harry Kane, or a 4-3-1-2, with Rooney behind Kane and Jamie Vardy. The Tottenham striker fits this role very well, as he fluidly moves to the wings, picking up balls and giving Rooney room to find the right spots within the opponent’s defence. Using a 4-2-3-1, the formations transforms into a 4-4-1-1 when defending. This shape would theoretically make variable zone coverage possible. Hodgson, however, avoids utilising these kinds of tactical tools – which perfectly sums up his time in charge.

Key element: versatile players who have competed at the highest level

***

Midway between an initiated rebuild and the 2018 World Cup at home, the team of Russia are not ready to keep up with the top competition in Europe. Fabio Capello was once designated to lead the Sbornaja back to glory, but eventually failed miserably.

In August of 2015 it was announced that Leonid Slutsky, the famous and ever wobbling coach of CSKA Moscow, would take a side job, as he was appointed as the new national coach in place of the outgoing Capello. The contract ran until the end of the Euro qualification tournament. Slutsky won all of his qualifying games and has continued to be in charge of the national team.

In August of 2015 it was announced that Leonid Slutsky, the famous and ever wobbling coach of CSKA Moscow, would take a side job, as he was appointed as the new national coach in place of the outgoing Capello. The contract ran until the end of the Euro qualification tournament. Slutsky won all of his qualifying games and has continued to be in charge of the national team.

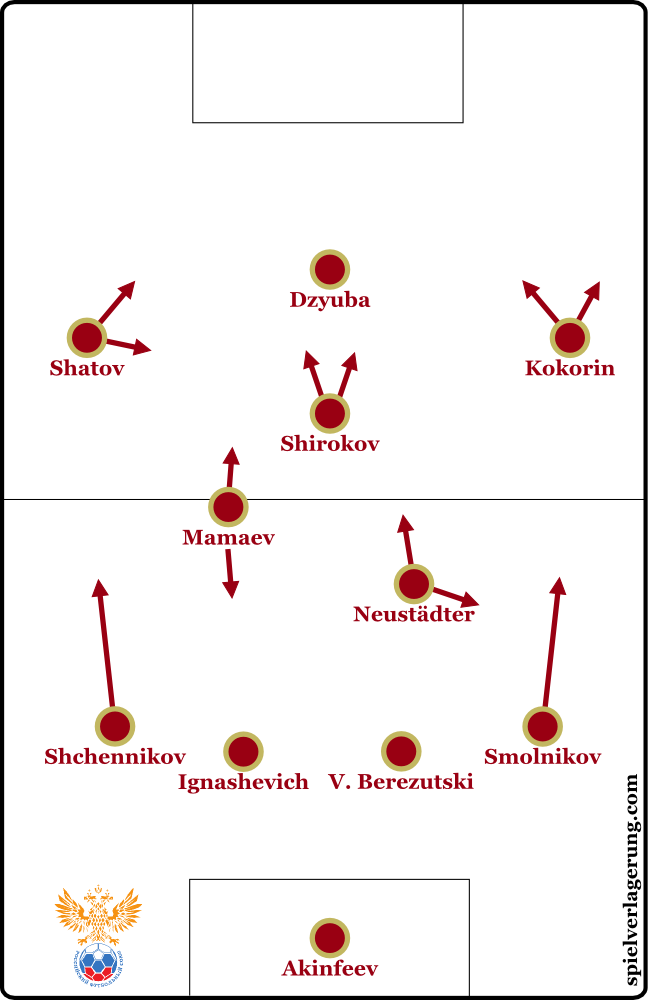

Similar to his CSKA side, Slutsky favours a clear-cut 4-2-3-1 system with both wingers playing very offensively, while one of the two centre-midfielders could come forward to link up with his team-mates. Alan Dzagoev, in particular, could have been this player, who does more than just sweeping in front of their back line. The 25-year-old, however, broke his foot during the last match of the season, which should give Pavel Mamaev an opportunity to show his playmaking skills in central midfield.

As implied, both wingers are roaming on the edge of the offside zone, preferentially sneaking behind the opposing defenders. In contrast, Russia have a rather slow, static centre-forward in Artyom Dzyuba, who stands at 6’5”. As Krasnodar’s Fyodor Smolov is more agile and cognitively quicker, Slutsky can alter the tactical approach up front by changing the lineup.

As for their build-up play, Russia usually use highly positioned full-backs who provide width, while both wingers run inside routes, supporting the lone striker or occupying zones in the backs of the opposing midfielders. Since both full-backs leave free space behind when advancing, both centre-midfielders have the opportunity to move to the outside, avoiding pressure from the opposing pressing block.

On a downside, a big hole between both centre-midfielders and the rest of the attacking part of the team emerges, which makes them vulnerable for quick turnovers in the middle, because the Russian team could be outnumbered immediately afterwards. All in all, their spacious shape when building up could be a weakness against intense passing-lane-orientated pressing.

Occasionally a single centre-back leaves his position and charges forward, which changes the focus of the opponents. If that is case, the ball-carrying centre-back plays a longer cross-field pass, so that his team-mates can attack the shorthanded side with a through ball.

After moving the ball forward, we usually do not see useless cross-passes. Only if an attacking winger stays out wide and gets isolated, with no chance to break through the opposing defence diagonally, he could take the short cut of simply knocking the ball towards the centre-forward, who is most likely on his own in these situations.

But normally the striker is rather a target player than just a physically impressive concrete block waiting for long balls to convert. When he drops back, trying to link up with the likes of Mamaev and Roman Shirokov, both wingers display lateral movement in the back of their team-mate, running through a horizontal slot to confuse the opponent’s defence.

The question remains whether Russia could become more hesitant facing top-tier competition. Not to forget that they charge forward too hard if things do not go their way offensively.

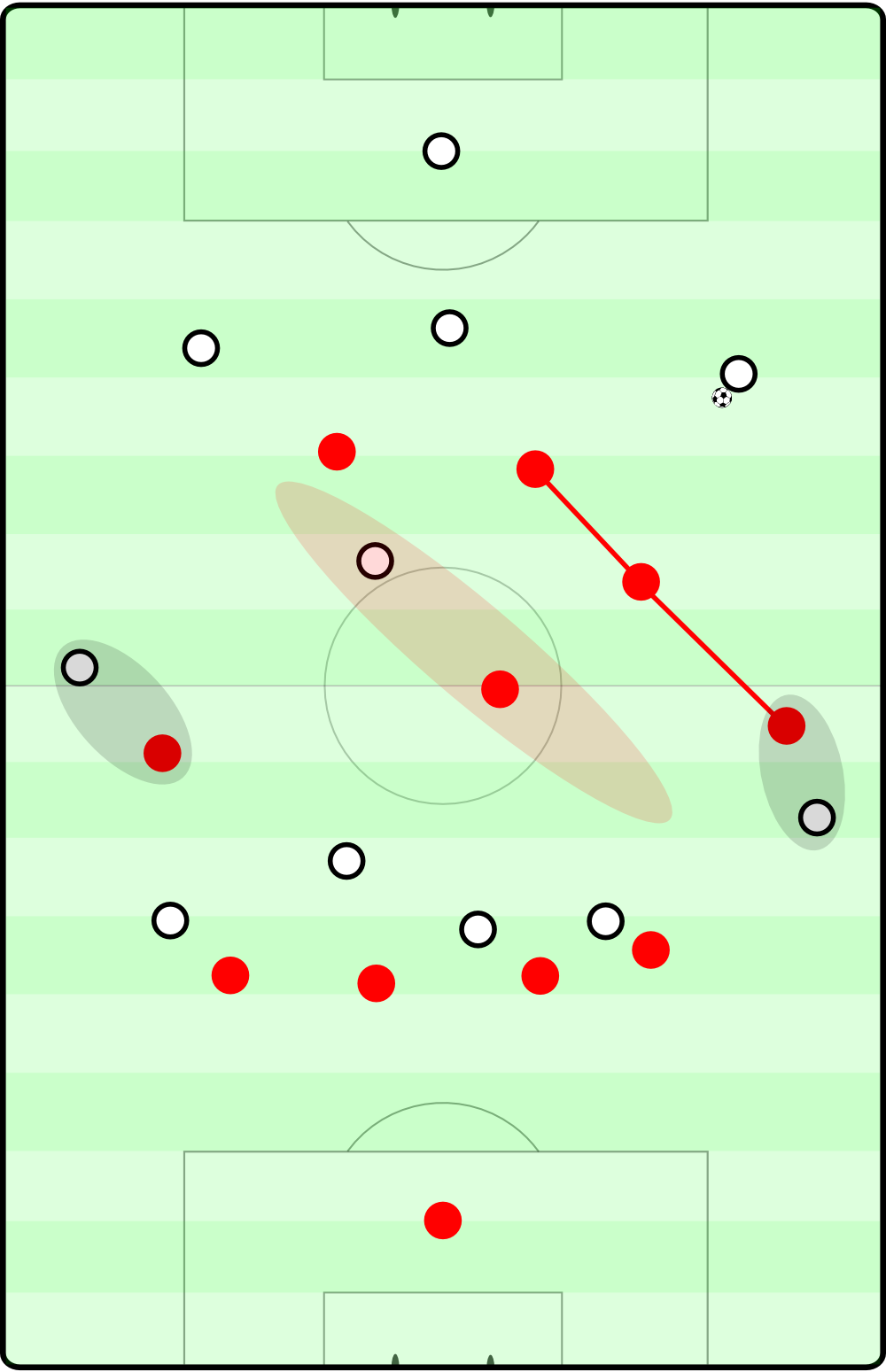

Defensively, on the other hand, the Sbornaja is barely able to guide the opposing build-up play towards the side lines. When pressing the opponents, the more progressive centre-midfielder rushes forward to cover the opposing number six player. Therefore, Russia usually defend in a 4-1-4-1 shape.

It is Slutsky’s approach to slow down the opposing attacks. His players are not suited for regaining ball possession quickly. His centre-backs are not fast enough to play a high line, forcing to negate longer sprints by opposing attackers. They can defend better in compact pockets than in open space in the middle third. This kind of vulnerability to fast breaks and a lack of controlling transition moments could very likely be stumbling blocks that stop them from getting past a favourite.

Key element: customary offence, fairly susceptible defence

***

Slovakia are the dark horse of this group. Having played an excellent qualifying tournament with a win over Spain in October 2014, Ján Kozák’s side could realistically win this group or realistically finish fourth. Everything is possible.

And while his team is hard to assess, Kozák himself seems to be an unknown on a larger scale. The Czechoslovak Footballer of the year 1981 had multiple spells at MFK Košice as a coach since the mid-1990s. Nevertheless, he has achieved something special: Since becoming independent in 1993, it is the first time that the Slovakia national team appear in the Euro tournament.

Being in a defending role against top teams most of the time, Kozák banks on a 4-1-4-1/4-5-1 formation with dynamic wingers and a fluidly moving centre-forward. Particularly when creating counter-attacks, the lone striker searches for negative space close to the opposing back line, linking up with his team-mates who follow up the ball after playing a long pass. Unfortunately, the centre-forward has to keep and defend the ball for quite some time before he can play a short lay-off pass. The distance between him and the rest of this team plays a factor when the Slovakian team are sitting up.

Being in a defending role against top teams most of the time, Kozák banks on a 4-1-4-1/4-5-1 formation with dynamic wingers and a fluidly moving centre-forward. Particularly when creating counter-attacks, the lone striker searches for negative space close to the opposing back line, linking up with his team-mates who follow up the ball after playing a long pass. Unfortunately, the centre-forward has to keep and defend the ball for quite some time before he can play a short lay-off pass. The distance between him and the rest of this team plays a factor when the Slovakian team are sitting up.

A possible attacking pattern could include the striker picking up the ball out wide. In the meantime, Marek Hamšík as the left centre-midfielder runs down into the penalty area, while both the right-winger and the right centre-midfielder move towards the right half-space, offering passing options for the ball-carrying forward.

When losing the ball up front, four or five Slovakians are usually out of the picture. That purportedly forces the deep-lying midfielder to come forward and try to apply pressure via counter-pressing. In reality, it simply exposes the zone in front of their back line, which makes it even more difficult to defend the looming counter-attack.

Slovakia, however, need intensity and a rapid-flowing ball circulation, because when building up out of their back-line they barely find the right pattern to move the ball calmly and to gain space at the same time. Both centre-backs are positioned deep, attempting to deliver the ball to a central-midfielder. When a full-back, who usually stands close to the centre-backs, gets involved he intends to play a diagonal pass to the winger in front of him, which makes the full-back’s actions predictable.

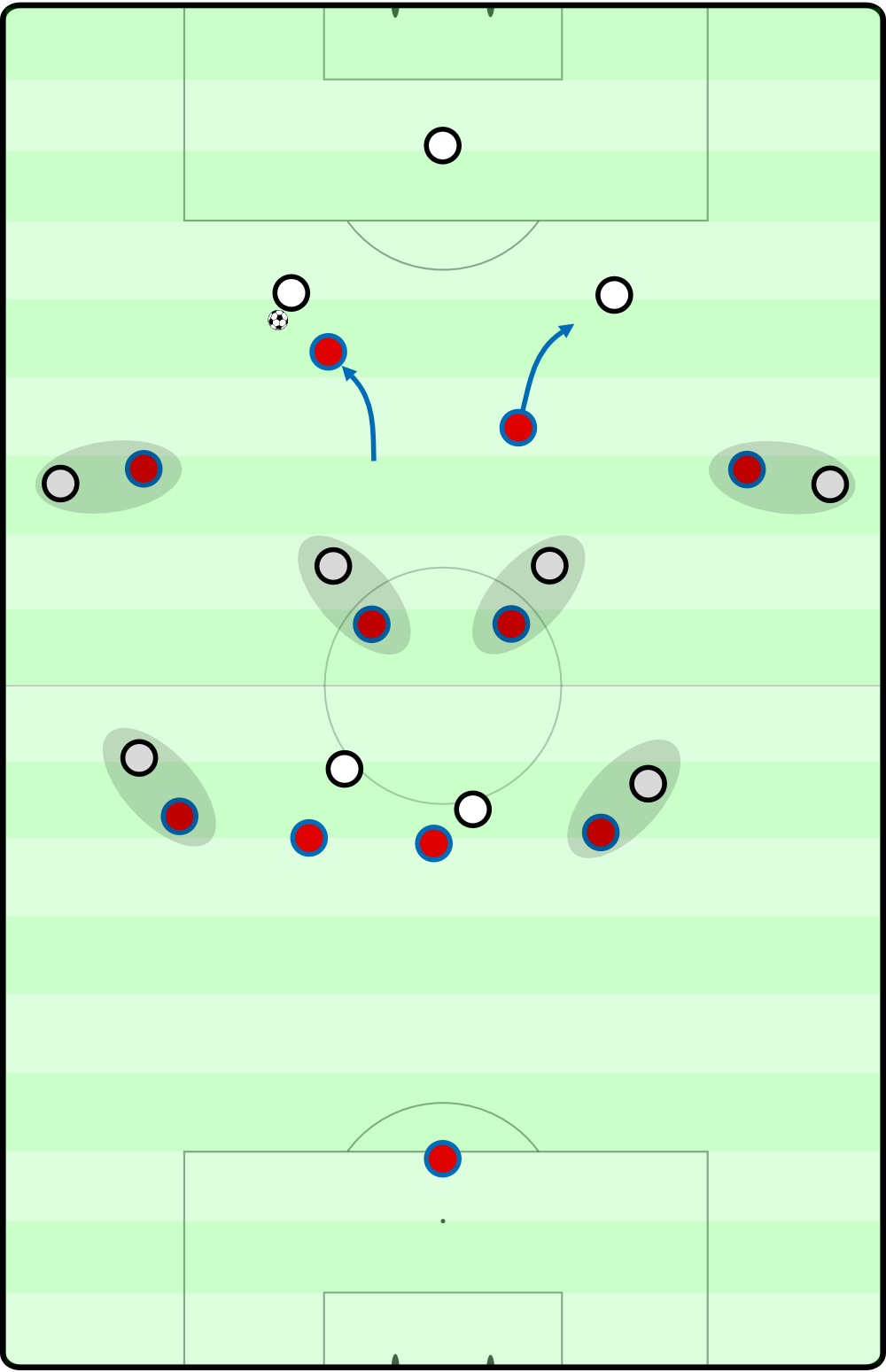

Defensively, the 4-5-1 basic formation changes into a 4-1-4-1 shape, with the centre-forward instructed to keep the opponent’s defenders busy. One particular element of Slovakia’s defensive system stands out: proper group tactical procedures. If a winger rushes forward, the centre-midfielder next to him changes his position to cover the deserted space. Defensive compactness is provided.

Or the ball-far winger drops back to defend at the offside line, which induces the midfielder next to him to move a few yards forward, using his cover shadow to shut down the passing lane.

As a negative effect, wingers chasing their respective opponent make the team vulnerable to quick one-twos. The opposing team could overload a wing to rip this kind of man-orientated defence scheme apart.

Also, the back line is susceptible to long vertical balls over the top, as they have a disadvantage in terms of speed. These issues would actually require a more intense pressing approach that applies pressure in zones downfield. Yet, Kozák sticks to his underdog strategy that makes Slovakia unpredictable – or dull every now and then.

Key element: hard-working defence and aging gunslingers in attack

***

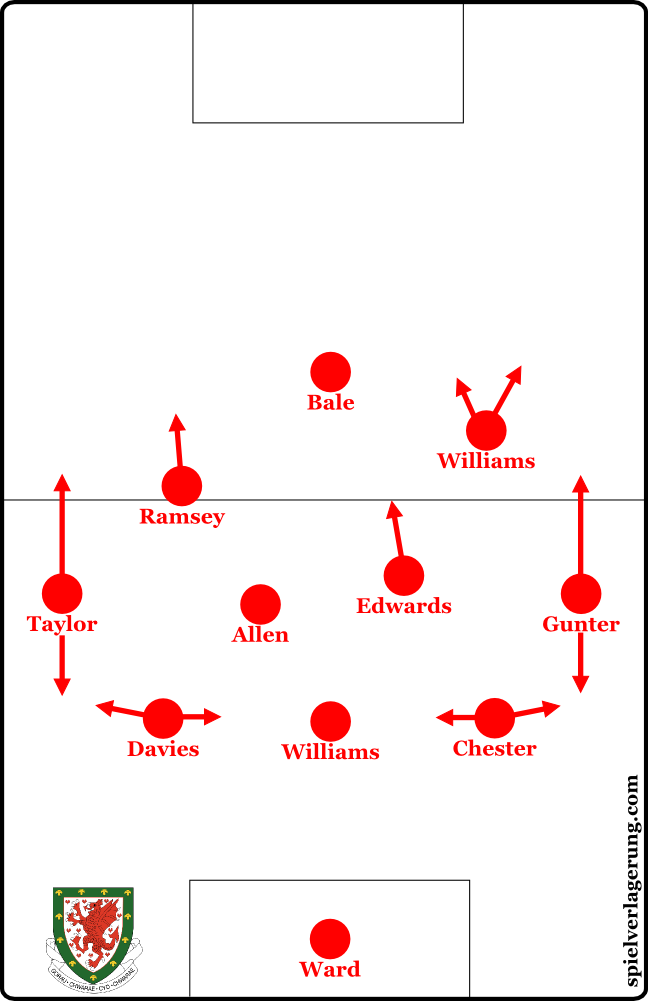

If you are still in search of a hipster team, do not look any further. Wales are the right choice. Chris Coleman, a former Real Sociedad and Fulham coach, has designed a tactical structure that emphasises uncommon yet effective defensive and offensive patterns on the field.

Coleman’s start as national coach could not have been any worse. After becoming the first Welsh manager to lose his first five games – and even considering retirement after a 6-1 defeat in Serbia – Coleman got his first win in October 2012, a 2–1 victory against Scotland. The team ended up being fifth in their World Cup qualification group, only three points ahead of Macedonia. Yet, Coleman laid the foundation for displaying outstanding performances in the months after the World Cup.

Coleman’s start as national coach could not have been any worse. After becoming the first Welsh manager to lose his first five games – and even considering retirement after a 6-1 defeat in Serbia – Coleman got his first win in October 2012, a 2–1 victory against Scotland. The team ended up being fifth in their World Cup qualification group, only three points ahead of Macedonia. Yet, Coleman laid the foundation for displaying outstanding performances in the months after the World Cup.

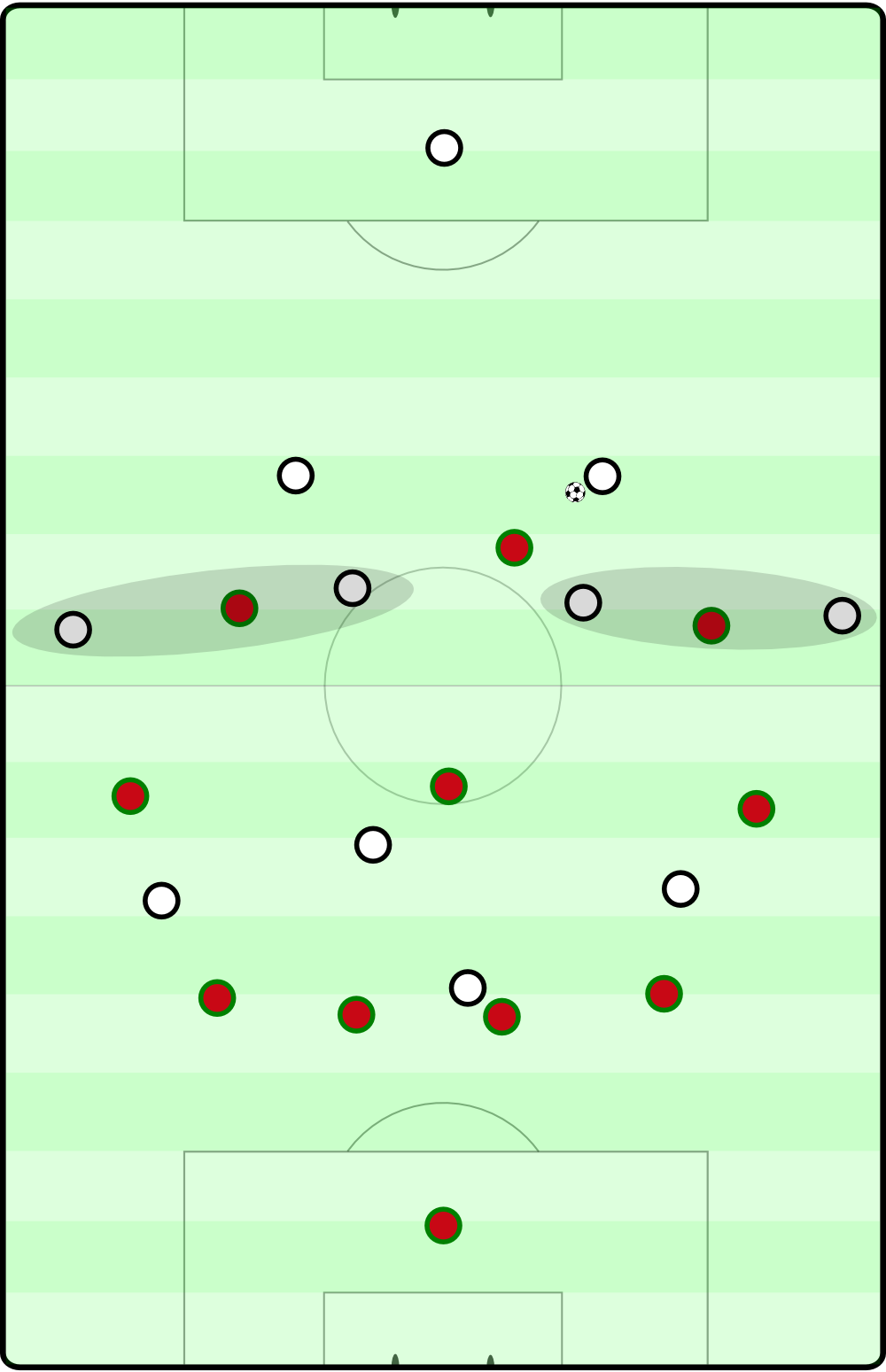

Only a loss in Bosnia and Herzegovina stopped them from winning the group ahead of a highly regarded Belgian team that could not defeat Coleman’s side in either of the two encounters.

A base of their game is the back three. It gives Coleman more flexibility regarding the shape of the midfield. Normally, he uses a 4-2-1 or 4-1-2 in front of his back-line. Defending their territory, the three players in the first line move to the half-way line, being horizontally compact to block central passing lanes. The line of four behind them usually defends man-orientated. As a consequence, there are many Welsh legs that can interrupt an opposing play in the middle of the pitch.

Even if an opposing number six player drops back, Wales maintain their pressing shape. Coleman puts emphasis on compactness, which is the prime principle in defence. It is therefore surprising when a midfielder occasionally leaves his position to apply pressure on the ball-carrier on his own. Both inside forwards are good at guiding the opposing build-up towards the side line, but it can only work when the team operate as a unit.

If anything, Coleman’s side become vulnerable in the latter stages of an opposing play. Then the wing-backs sometimes drop back too early which leaves the zones next to the centre-midfielders open. Long balls can target these weak spots. There defensive mechanisms in terms of protecting the own penalty box work properly when both wing-backs stay near the side line, while centre-midfielders hare back to fill the gaps between the wing-backs and the centre-backs. All three centre-backs are normally positioned within a few yards to cover the danger zone.

As for their build-up play, the three centre-backs stand close together at times, looking for a centre-midfielder in the half-spaces in front of them. Particularly the technically gifted Joe Allen is a receiver of short build-up passes which initiate Wales’ attacks. When having a longer spell of possession the Welsh players tend to drift apart, with forwards waiting near the offside line and wingers – even on the ball-far side – being positioned out wide.

The Dragons strongly rely on their transition plays. After winning the ball, the Welsh midfielders improvise combination plays, frequently searching for diagonal gaps to the wings. As most of their midfielders who are asked to drag the ball through the second third are not that resistant against intense pressing, they quickly need to find open men to avoid turnovers.

After losing possession, Coleman’s side try to return to their defensive shape as fast as possible. That means the Dragons are not really focused on aggressive counter-pressing. Structure is the key as far as their defence is concerned.

Their defensive compactness is a blessing and a curse at the same time, though. Wales are able to win the ball rather quickly in the middle, but heavy traffic and no open men in outside zones make it difficult to escape these tight pockets. Due to their vertical compactness there is no recipient for immediate passes towards the opposing back line. Short precise passes are required. However, the Welsh players run out of gas and ideas from time to time.

The hope is that Gareth Bale and Aaron Ramsey, who are crucial parts of their attack, can solve these problems. Bale is mostly fielded as left-winger or centre-forward, but could also play on the right side, while Ramsey feels comfortable as a number ten/winger hybrid and therefore as a connecting player between midfielders and forwards.

Bale’s varying runs – sometimes he roams around at the outside; another time he sneaks between opposing defenders – are threatening for every defence. The Real Madrid star, however, tends to strike out on his own when the rest of the team show a lack of creativity. The 26-year-old could be the X factor in their Euro campaign.

Key element: uncommon tactical patterns paired with the sublime skill sets of Bale and Ramsey

Group C

Throughout the 2014 World Cup, it looked like Joachim Löw and his team, an assembly of young and highly gifted players, would once again fail to win the big one. Yet, eventually Germany triumphed against Argentina, thanks to an extra-time goal scored by Mario Götze. Löw crowned his career, but did not lose his motivation to develop his team further.

The months after their World Cup win were hard, though, as Germany clearly struggled to find the right balance between the system they played in Brazil and appropriate adjustments to qualification matches against the likes of Poland, Ireland and Scotland. Löw’s side lost more than once, but made progress regarding their defensive stability and offensive interplay.

The months after their World Cup win were hard, though, as Germany clearly struggled to find the right balance between the system they played in Brazil and appropriate adjustments to qualification matches against the likes of Poland, Ireland and Scotland. Löw’s side lost more than once, but made progress regarding their defensive stability and offensive interplay.

It is not the question whether the German team are talented enough or not. Particularly in midfield, Löw has the agony of choice. But not only that, he moreover has tested a variety of formations like 4-3-3, the system they employed at the World Cup, 4-2-3-1, 3-5-2 and 4-2-4.

Starting from their back line, Manuel Neuer is an important part of their build-up play, because the technically capable goalkeeper can help to bypass high pressing lines by playing precise medium-range passes to the anterior level of offence. Furthermore, centre-backs such as Mats Hummels and Jérôme Boateng stand out due to their progressive style including penetrating runs into the space between the opposing lines.

Overall, the German team offer an intriguing variety of tactical movements, although they tend to ignore the central zones in some matches, which finds expression in both centre-midfielders sitting right in front of the back line instead of one number six player advancing to provide connections between defenders and forwards.

The reason Germany are that hesitant on some occasions is their heavy focus on defensive stability when they fear the threat of opposing counter-attacks. Then Löw’s side avoid vertical passes across the middle, especially when they employ a 4-2-4 shape in which the counter-pressing does not have as big an impact as in other systems because of the stretched formation and the gaps between the players.

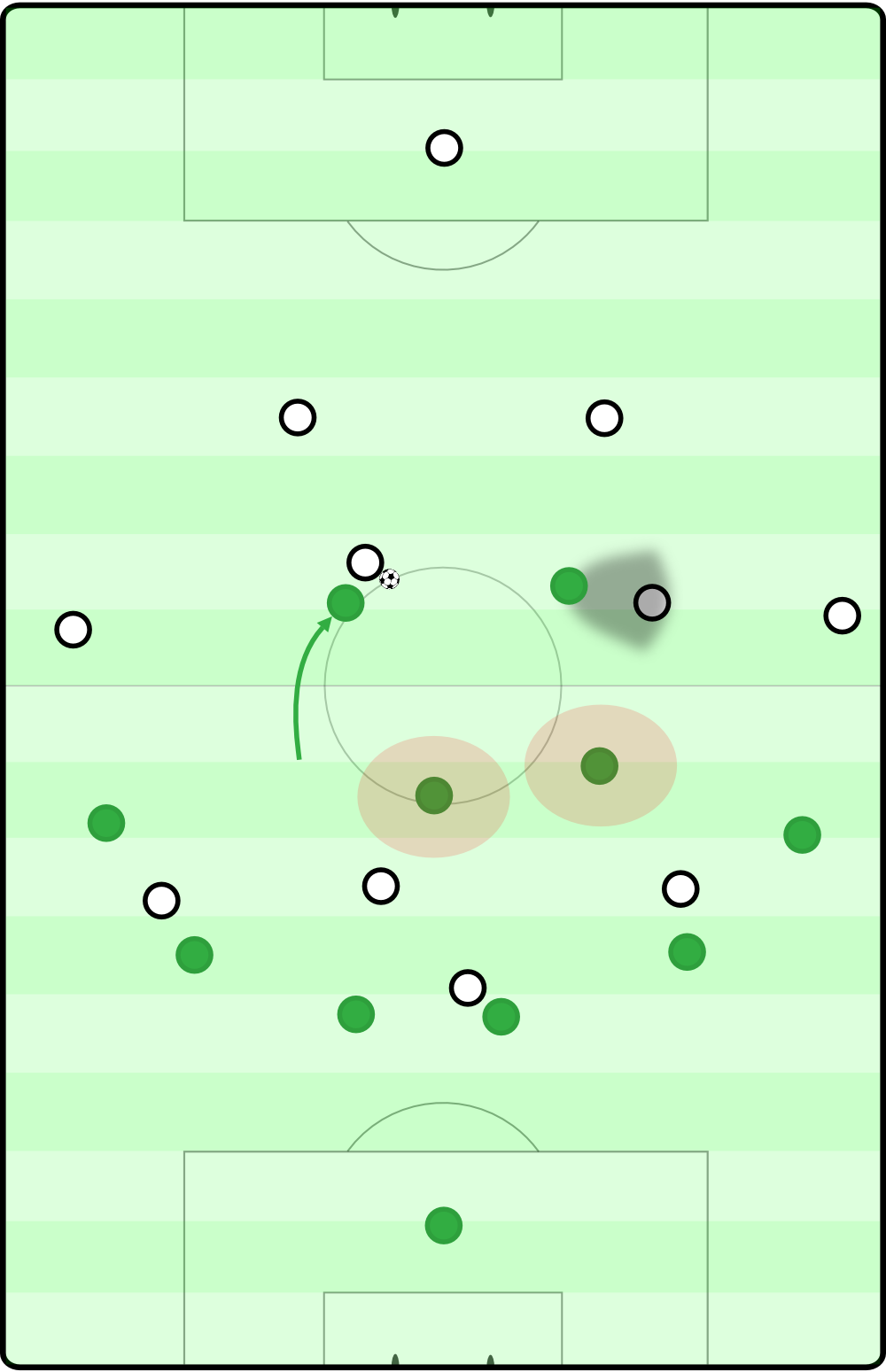

With that being said, the German team can be tremendously impressive if all the pieces fit together. A fluidly moving and shifting offense featuring Götze, Mesut Özil and Thomas Müller must be a scary thought for every opponent. Löw’s offensive concept usually relies on overloading one half-space, as certain lateral zones are primary starting points for the second phase of their build-up play.

Several steps are necessary to set up breakthroughs or runs behind the opposing back line. Since Germany do not have a classic centre-forward whose strength is his physical superiority, attacking patterns become way more complicated, but also more surprising to opponents at the same time. Some attacking mechanisms do not work to Löw’s full satisfaction yet, which can cause solo attempts and a lack of interplay in the last third, but this is complaining about problems the vast majority of national teams would love to have.

If there is any real weakness other teams could capitalise on, it is Germany’s defence – more specifically the defensive transition after turning the ball over. In particular, both full-backs do not enjoy much help on the flanks and the central defenders are vulnerable to long balls over the top.

Hummels and the other centre-backs are good at anticipating the movement of the ball as well as the movement of opposing strikers, yet they should not get themselves into long running duels in Germany’s half. Overloads in the half-spaces when they are in possession can help to increase their access to the ball in case they lose it, and Löw has undoubtedly worked on this aspect.

Hummels and the other centre-backs are good at anticipating the movement of the ball as well as the movement of opposing strikers, yet they should not get themselves into long running duels in Germany’s half. Overloads in the half-spaces when they are in possession can help to increase their access to the ball in case they lose it, and Löw has undoubtedly worked on this aspect.

The German head coach, moreover, tested a back three on a number of occasions, but was not happy with the outcome. His team displayed a lack of balance when playing with three defenders at the back. Either both wing-backs sat too deep and could not support the ball circulation when the rest of the team moved downfield, or both wingers were positioned high up the pitch and did only little work in defence. Plus, the outer centre-backs are not used to this kind of tactical shape, so that they did not show the appropriate aggressiveness when asked to blitz out of the back line to intensify Germany’s counter-pressing. All in all, unreliable chain mechanisms and a lack of coordination have made it unlikely that the German team could field a back three in a match they take seriously.

To end on a positive note, Löw’s side have shown improvements in terms of how they break down teams who only concentrate on parking the bus. In these games, Germany do not stick to simple wing attacks anymore. Rather, they attack the small gaps in between the opposing defenders, which is possible thanks to a high number of talented pocket players up front. They try to outnumber defenders in half-spaces or on the edges of the 18-yard-box, while setting up combination plays involving the likes of Özil and Müller.

As far as personnel and tactics are concerned, Löw has countless options. Easier said than done, he just needs to know how to use these options.

Key element: almost infinite supply of creative midfielders and forwards

***

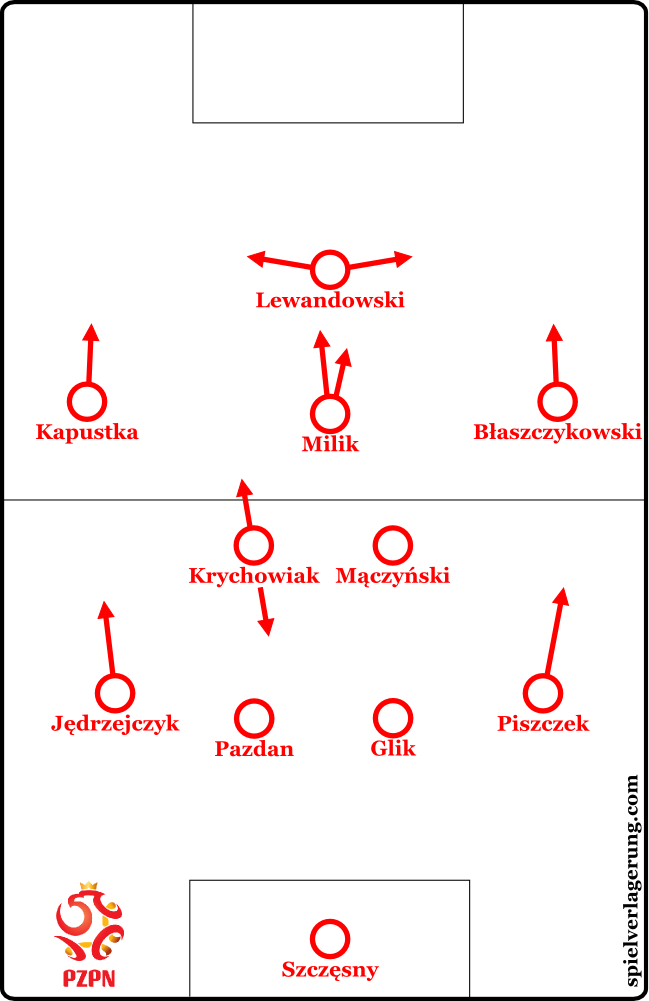

After the disaster Poland experienced in 2012, when the hosts of the Euro went out after the group stage, this time the national team are supposed to do significantly better. Poland finished second in their qualifying group behind Germany, but gained a 2-0 win over the reigning World Champions in October 2014.

Of course, head coach Adam Nawałka has two stars and key players he can count on: Bayern Munich’s Robert Lewandowski up front and Sevilla’s Grzegorz Krychowiak in central midfield. Also, the former captain Jakub Błaszczykowski could be a factor if he stays fit and peaks on point.

Poland’s basic formation is set in stone. They play a quite simple 4-2-3-1 system without any kind of special elements. It’s only always a question prior to matches whether an auxiliary striker like Arkadiusz Milik plays behind Lewandowski and supports the centre-forward adequately, or a more defensive-minded midfielder like Krzysztof Mączyński gets his chance in the number ten role.

Poland’s basic formation is set in stone. They play a quite simple 4-2-3-1 system without any kind of special elements. It’s only always a question prior to matches whether an auxiliary striker like Arkadiusz Milik plays behind Lewandowski and supports the centre-forward adequately, or a more defensive-minded midfielder like Krzysztof Mączyński gets his chance in the number ten role.

From a macro-perspective, Poland’s offensive strategy can vary from game to game. They are not solely concentrated on one particular concept. For instance, they can rely on counter-attacks and therefore sit deeper defensively to block the central zones and win the ball on the flanks, which usually ends up in quick transition plays through the wings.

Most of the Polish counter-attacks include long cross-field passes immediately after winning and securing the ball to open the field and to enter wider zones. Interestingly, right-back Łukasz Piszczek does a lot of work when it comes to wing attacks. Similar to both wingers who have to chase back to provide double coverage when Poland focus on stabilising the defence, he bombs up and down the outside lane showing great fitness.

Especially against dominant possession-orientated teams, Poland can possibly become a threat. However, the Białe Orły have to prove that they can create plays without setting them up with turnovers. When trying to break down concentrated defences, they lack the creativity that is needed to create breakthroughs. Some group tactical mechanisms, for example the coordination between two players on the flank including precise lay-off-passes and sending the runner down the field by sliding a pass into his path, already work perfectly.

Poland are able to bring the intensity into match if they smell blood. Yet, Lewandowski is in need of support so that he can pick his spots in between the defenders. A player who provides connection high up the pitch is required; otherwise Lewandowski has to assist himself. And in general, it could be problematic if Lewandowski starts to think he has to run the show all by himself.

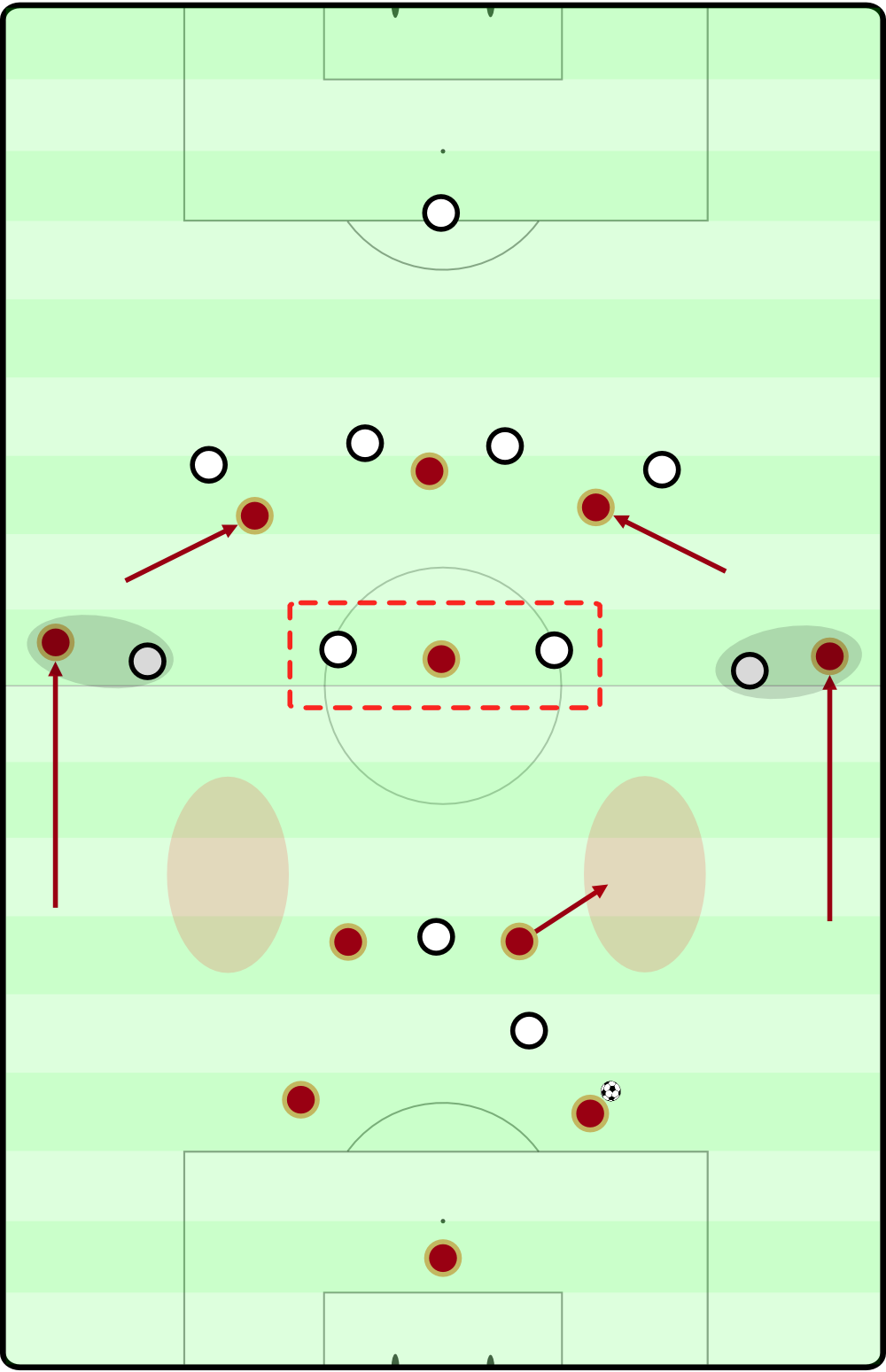

But to even reach the spaces high up the pitch, Poland have to gain ball possession first. Nawałka’s side can chose from a variety of defensive settings. They are not forced to wait and sit deep against upper echelon opponents, even though this is what they do at times. In this case, double coverage on the flanks as well as a compact centre are a prerequisite to protect the own 18-yard-box. A compact central block – including man-marking or not – is able to guide the opposing team to the outside, where the ball-carrier can fall into Poland’s clutches.

It is also possible that they employ a 4-4-2, pressing with two runners up front who rush towards the opposing centre-backs who are about to play the first passes, and force them to make a quick decision. Plus, these runners then chase after the ball for a few more seconds. This is the aformentioned intensity that characterises their style of play on both sides of the ball.

Key elements: flexibility and adaptability

***

Like Poland, Ukraine were co-hosts of the 2012 Euro and were eliminated after losses to France and England. Unfortunately, football has had to take a backseat recently due to the political turmoil and the conflict with Russia, shaking up the state dramatically.

Mykhaylo Fomenko’s team will compete in France anyway. And they are ready to prove doubters wrong, even though the shown performances throughout the qualification tournament did not boost their confidence. They finished only third in their group, as they were beaten by Spain and Slovakia, but emerged victorious against Slovenia in the play-offs.

Mykhaylo Fomenko’s team will compete in France anyway. And they are ready to prove doubters wrong, even though the shown performances throughout the qualification tournament did not boost their confidence. They finished only third in their group, as they were beaten by Spain and Slovakia, but emerged victorious against Slovenia in the play-offs.

Ukraine prefer an ordinary 4-2-3-1 with crafty and sturdy wingers who are the pivotal points of the team’s offense. When building up, though, they often employ a 4-1-4-1 shape as two centre-midfielders float around to link up with team-mates in various spots on the field, play lay-off passes to the defenders and hence cope with the opponent’s man-to-man coverage.

Aggressive wingers like Andriy Yarmolenko orientate themselves towards the offside line, which means they sometimes start their forward runs even before Ukraine take over the ball. Forward movement paired with deep passes are characteristic for their offense, yet these elements make them prone to opposing transition plays, as the possibility of losing the ball quickly is comparatively high.

On the other side, a slow build-up makes them vulnerable to aggressive pressing. Ukraine have to find a way to move the ball to the midfielders without rushing too hard while also not being stopped by the opposing defence early on.

Personnel-wise, their defence only changed marginally in the recent past, so they know each other very well at the back. Ukraine’s defence bank on physical elements. Especially deep in their territory, they seek body contact and one-on-one situations, or even go for a sliding tackle.

Unfortunately for them, this alignment sometimes leads to their making a dash at the ball while neglecting the responsibility regarding zone coverage, so that cross-field passes can catch them off-guard or dribbles into the pockets tie up Ukraine’s defenders. The amount of last-man tackles that prevent successful counter-attacks speaks for itself and is caused by the non-existence of well-working group tactical mechanisms.

Key element: skills trying to match to aspirations

***

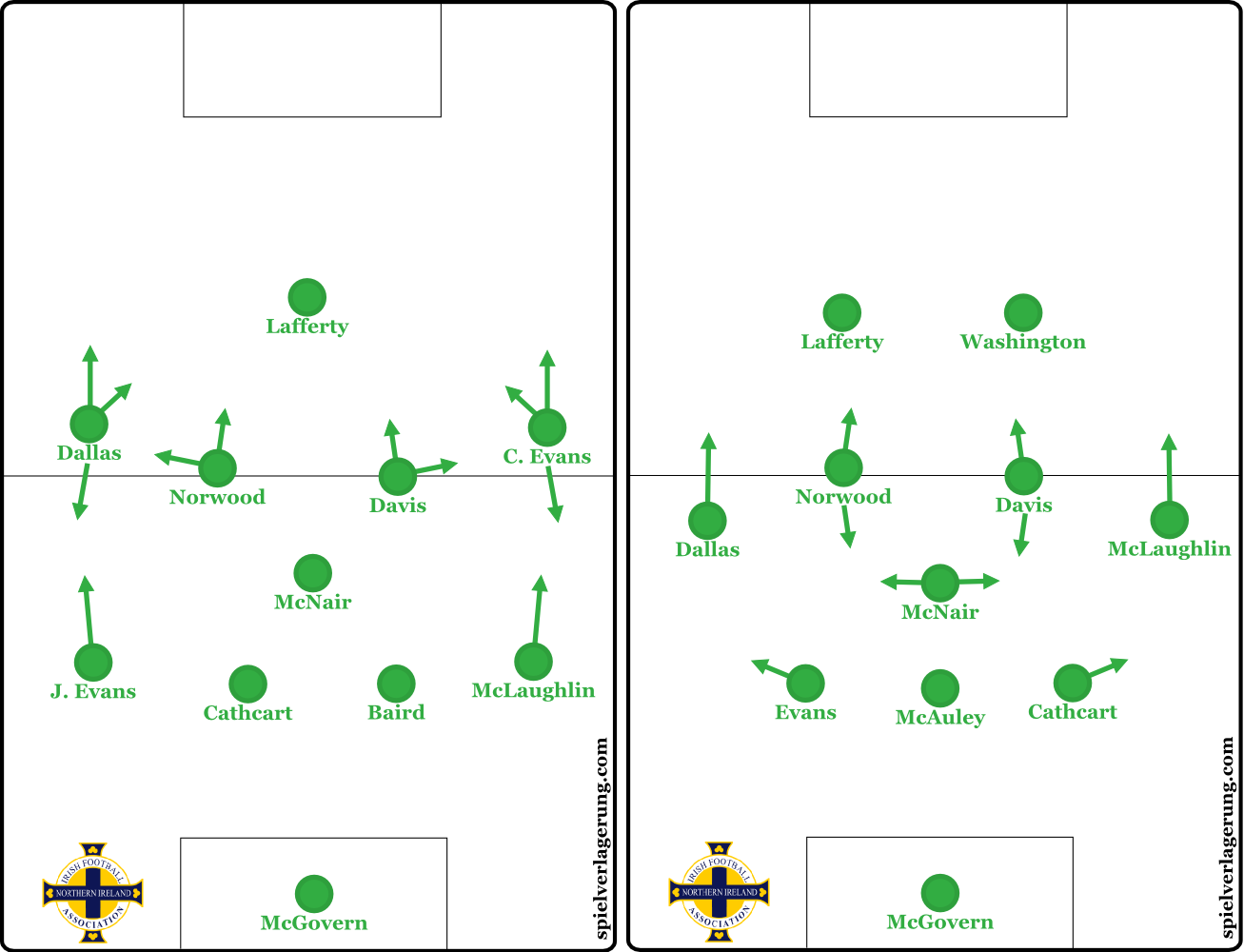

October 8 2015, was a historic day for football in Northern Ireland, as the national team qualified for their first ever European Championship after beating Greece 3-1 in Belfast’s Windsor Park. Michael O’Neill, who became manager in February 2012 after Nigel Worthington had resigned in October after a poor Euro qualification campaign, has formed a unit composed of players determined to write their own little success story.

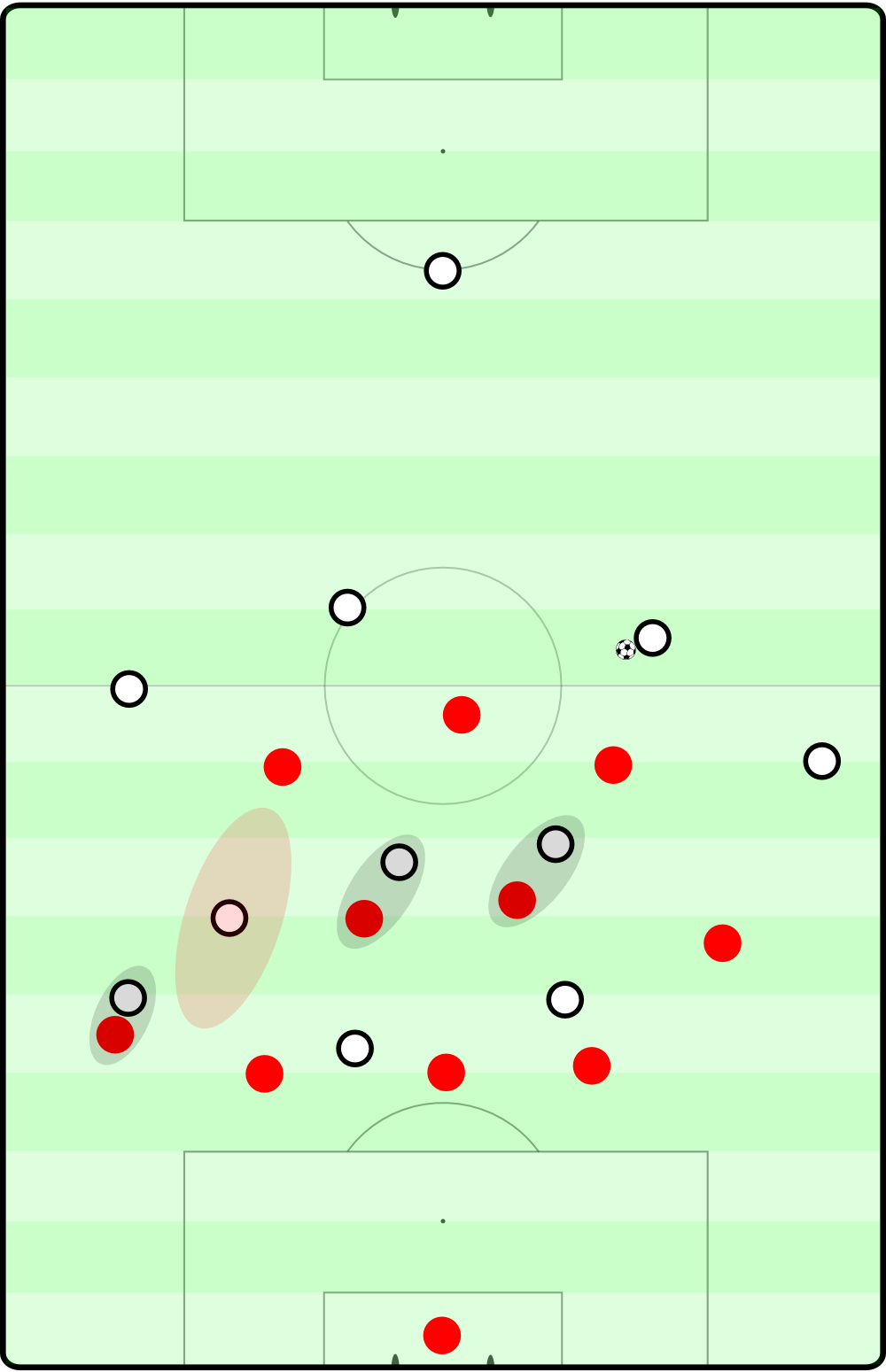

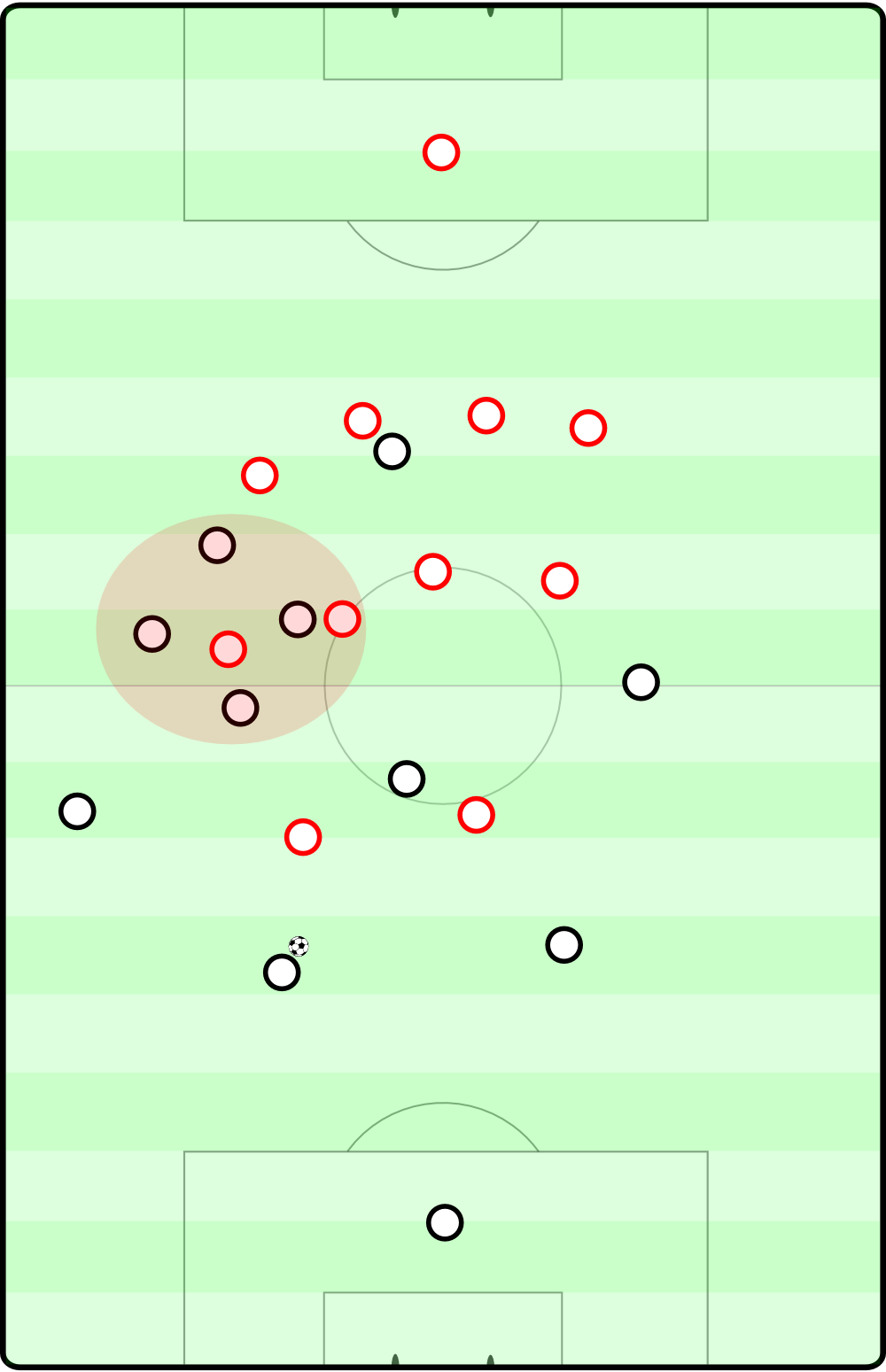

Offensively, Northern Ireland offer a few intriguing tactical pieces in a 4-3-3 shape, including widely positioned number eight players and wingers right in front of them. This sort of system provides presence up front to a greater extent as opposed to other teams at a similar level. On a downside, the hole between the lines weakens their ability to utilise intense counter-pressing in case they cannot tie up the ball high up the pitch. Moving forward as a whole, Northern Ireland’s centre-midfielders display great fluidity in their movement that helps the centre-forward who does not have to roam through the higher zones alone.

Having said that, the high number of long balls in the initial build-up play, without good cause and without precision, makes it easier to defend the Green and White Army, given the fact that the attacking players usually do not have enough time to position themselves between the opposing defenders. Overall, Northern Ireland’s vertical and straight attacking style reduces the precision of their plays.

In defence, O’Neill’s team want to generate early turnovers, particularly against weaker competition. Their aspiration to be a dominant side separates them from many other national teams. In a 4-5-1/4-3-3, one centre-midfielder usually rushes towards the ball carrier, guiding the opposing build-up to one side, while the other midfielders control the space behind.

On other occasions, the three midfielders form a wide block while both wingers guard deeper wing zones against diagonal passes. In defensive transition, when there is not enough time to set up this kind of defensive formation, both wingers adapt to the situation by keeping higher positions.

Most of the time, both full-backs are positioned a few yards higher than full-backs usually are. The purpose is to not allow the opposing wingers to receive the ball properly. Northern Ireland’s full-backs want to interrupt the flow of the attack as soon as the ball enters the respective zones at the outside of the back line.

It has to be noted that O’Neill has recently tested a system with a back three and two attacking wing-backs. That said, no matter which formation they use, Northern Ireland are not much of a threat offensively, though can score after set-pieces and accurate crosses. If teams are able to bypass their first pressing line, they seem to be lost in their own third, being rather incapable of shutting down the driving and passing lanes towards their goal. However, their tactical approach, which includes a proactive style on both sides of the ball, is promising at the very least.

Key element: interesting defensive structures combined with a strong mind-set

Group D

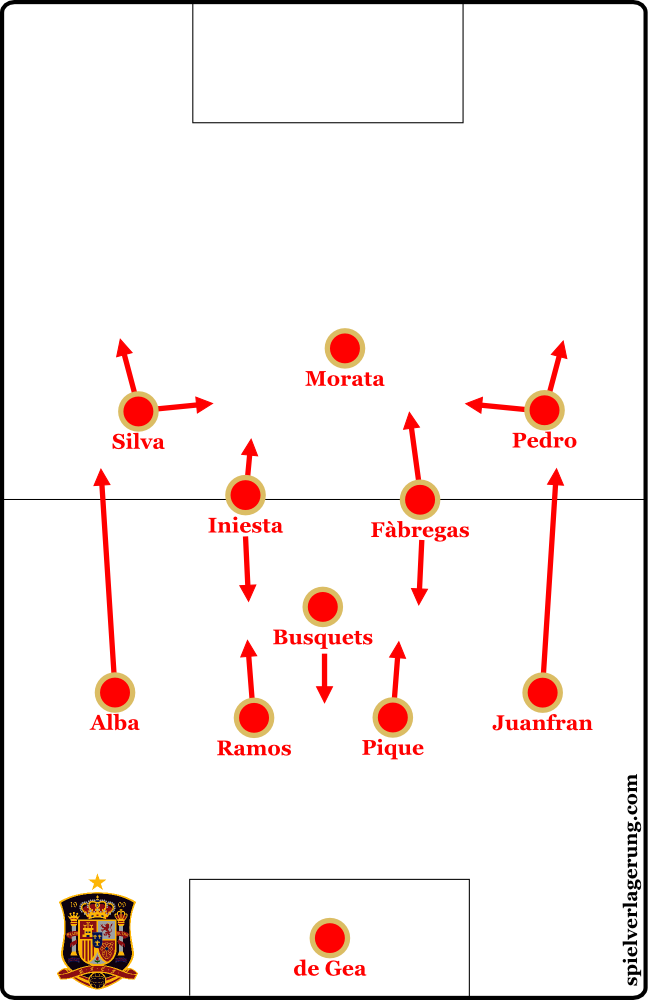

The golden generation of Spain has experienced a lot of farewell addresses during the last few years. Yet, La Furia Roja is determined to prove the critics wrong and show their class at least one more time. The stage is set.

Especially Andrés Iniesta seems to be the personification of Spain’s revival. In Vicente del Bosque’s 4-3-3 system, the 31-year-old is a pivotal point offensively and defensively. Although some could expect Sergio Busquets to be the right kind of player to provide presence in the middle of the park, it is Iniesta who conducts the team tremendously.

Especially Andrés Iniesta seems to be the personification of Spain’s revival. In Vicente del Bosque’s 4-3-3 system, the 31-year-old is a pivotal point offensively and defensively. Although some could expect Sergio Busquets to be the right kind of player to provide presence in the middle of the park, it is Iniesta who conducts the team tremendously.

As almost always during Del Bosque’s stint as national coach, the team’s system bases on a Barcelona-like approach, with at least one attacking winger playing as a second inside-forward, even though La Furia Roja lacks the tactical radicalism we have seen from Barcelona over the years.

When building up, both centre-backs usually attack the half-spaces, as we have to keep in mind that Spain usually play against deep-sitting opponents. Busquets drops back only a few times during a match, because it is not necessary to outnumber the opposing team at the own back line. However, it has to be mentioned that the Iberians sometimes misplace a pass in the early build-up play, which invites opponents to start transition attacks through the open field.

Busquets is not involved in the build-up play to the extent he should be, as he often waits in front of the first block, being positioned too close to the centre-backs. Meanwhile, Iniesta or the second centre-midfielder drops back and picks up the ball.

Afterwards, there are repetitive attacking patterns that trigger reactions by the players up front. For instance, after picking up the ball in a deep position a centre-midfielder advances through the half-space, which prompts the winger on this side to move to the inside. Therefore, the ball-carrier now has a vertical passing option so that he could bypass the opposing midfield line easily. Then the centre-midfielder moves forward. While the focus of the whole play seems to be on this side, it is just a way to fool the defence, because a quick cross-over pass normally finds an open man on the other side of the field.

Since both wingers tend to push inwards, the full-backs are asked to provide width in the last third. And with Jordi Alba on the left and Juanfran on the right, Del Bosque has the perfect players to do so. Speaking of fitting players, Diego Costa, unfortunately, looked like he’s out of place most of the time. The Chelsea forward prefers a different attacking rhythm and puts emphasis on other aspects than the rest of team. Del Busque eventually decided to relinquish Diego Costa.

That said, the team have to increase their presence in the backfield when the striker and the wingers roaming near the offside line, no matter who plays in the middle. Potential rebounds should be picked up immediately to continue the spell of possession.

A possession-based side like Spain have to show intensity and awareness in terms of counter-pressing. In their case, the individual counter-pressing quality seems incredibly high, although their collective counter-pressing is in need of improvement. Nevertheless, due to constant forward runs which often create a 2-1-7 shape, they automatically put pressure on the opponents after turnovers. Plus, in Busquets they have the perfect sheriff in the backfield who ordinarily cannot be beaten.

After regaining ball possession, they can create short-range combination plays due to an overall compact shape. Moreover, both full-backs keep their position out wide, which means that diagonal passes to the outside can leaven the intense situation.

Against the opposing build-up play, Spain’s centre-forward solely keeps the centre-backs busy, using intelligent runs and horizontal cover shadows. The opponents then have only limited options to move the ball across the field. On a downside, the lack of physicality among Spain’s midfielders and the lack of speed among the defenders can put them in bad situations. At the back, the defenders occasionally apply man-to-man coverage, but mostly try to guide the opponents towards the side line by standing right in front of the ball carrier, turning their hips to the outside.

Overall, Spain’s defence perform consistently well, yet have not been tested that much throughout the qualification stage. If their possession dominance declines when playing against top-tier competition, it possibly leads to lower counter-pressing intensity.

Nevertheless, nobody should count out Spain. They have years of high level performance under their belts. And the influence of tactically sophisticated football displayed in the domestic league definitely helps Del Bosque.

Key element: highly talented players with a great understanding of the Juego de Posicíon philosophy

***

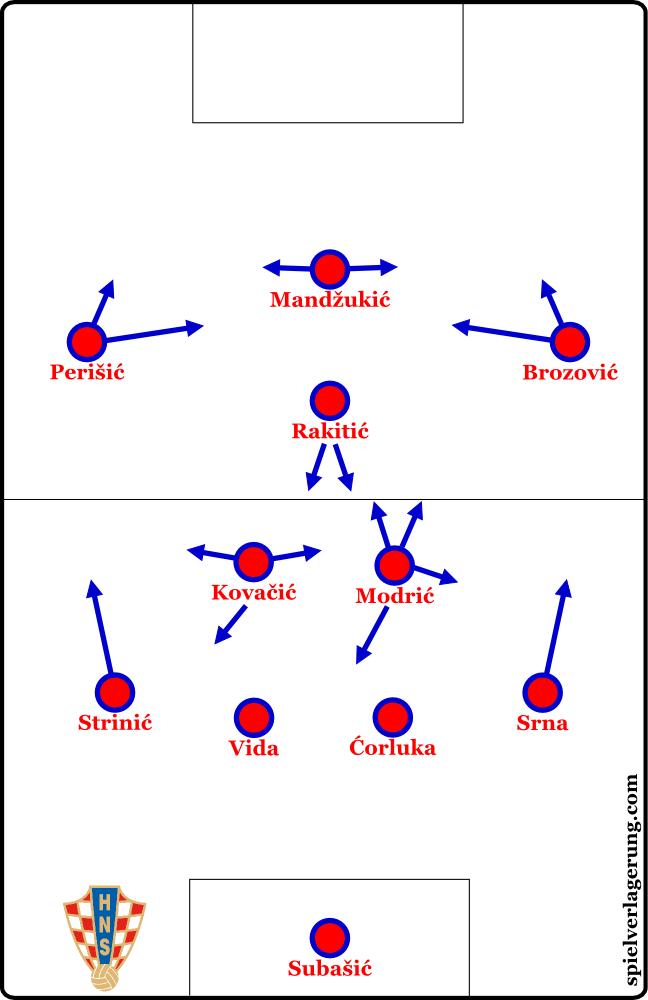

It is the burden of Luka Modrić, Ivan Rakitić, and Mateo Kovačić to carry Croatia on their shoulders. The hopes are high, as this team probably remind many fans of the 1998 World Cup squad that reached third place in France. Now, the French pitches could once again witness the success of Croatian players in red-whited-chequered jerseys.

The Vatreni finished second in their Euro qualifying group, four points behind Italy. Croatia only lost once, as Norway beat them in Oslo in September 2015. Drawing twice against Italy and beating other opponents such as Bulgaria decisively, passing the qualification stage was hardly in question, even though Croatia were deducted one point after charges for racist behaviour in the match against Italy at Split’s Stadion Poljud in June 2015.

Nevertheless, the Croatian football federation sacked Niko Kovac after losing against Norway, but mostly due to bad performances displayed by a team that has a very high ceiling.

Ante Čačić, a 62-year-old veteran who coached almost two dozens of teams throughout his career, was hired as the new head coach in late-September. He prefers to play a customary 4-2-3-1 system that involves the most creative players in midfield.

Ante Čačić, a 62-year-old veteran who coached almost two dozens of teams throughout his career, was hired as the new head coach in late-September. He prefers to play a customary 4-2-3-1 system that involves the most creative players in midfield.

Offensively, Croatia show the desire to overwhelm opponents, yet make intelligent decisions when entering the opposing half of the field, thanks to the likes of Modrić and Kovačić. At times, they even break up attacks and play the ball backwards to restart the play. Croatia rarely take the sledgehammer out of the box to break down the wall. Though, sometimes deep diagonal passes towards the wings shape their attacking plays. Plus, both attacking wingers tend to constantly make runs behind the back line, which even intensifies the offensive rhythm.

When building up, one of the centre-midfielders drops between the centre-backs, so that four players stand on a vertical line, which is not perfect in terms of how to change levels during an attacking play.

However, when the centre-midfielders avoid dropping back, Croatia’s centre-backs have a hard time moving the ball forward. They are barely able or do not have the confidence to play the ball through vertical slots. Therefore, most of the early passes in the build-up play are received by one of the full-backs or the deep centre-midfielder, so that Croatia do not bypass the opponent’s first pressing line.

Defensively, the back four has the tendency to move backwards too early, which causes big gaps when the midfielders are still fighting for the ball. Čačić actually wants to see his team narrowing the zones between the lines. But this, on the other hand, could lead to a defensive shape that is too flat and leaves the backfield open.

On a positive note, Modrić and the other centre-midfielders provide intensity and smart decision-making in terms of counter-pressing, while the wingers cover a lot of space through ball-orientated movement.

Overall, Čačić keeps Croatia’s tactical structure very simple, despite having high-level playmakers. Rakitić is not the perfect player in the number ten role, because he does not want to run in between the defenders. Rather, he roams around in the middle third or drifts towards the wing zones.

If Croatia are able to find their flow offensively and play effective passing combinations, there are only a few teams who can stop them. Individual movements are good. Yet, a lack of synergy effects between the several parts stops them from being a more dangerous force. As their ball circulation sometimes seems to be ineffective and the ball mostly moves to the wide open man, instead of penetrating tight zones, one player could lose his nerve at one point, knocking the ball forward in sheer desperation.

Given their potential, Croatia’s players know they have to perform well against the best competition in Europe. It is easier said than done though.

Key element: putting all pieces together to work as a unit

***

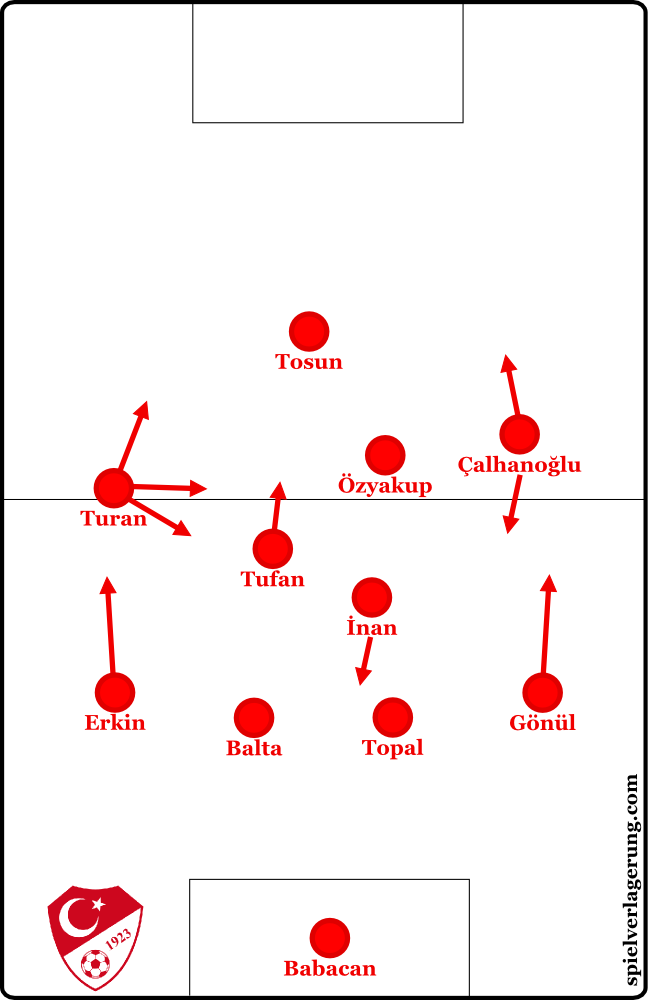

Turkey have lived through ups and downs for quite some time. They started fairly poor in the qualification group stage, losing to Iceland and the Czech Republic. They also drew the next game against Latvia, lost in a friendly clash against Brazil, and closed the year of 2014 with a brink of success by beating Kazakhstan. However, two wins over the Netherlands, who had beaten them in the last qualifying match for the 2014 World Cup, paved the way to advancing to the final tournament.

Despite having a big group of talents, Arda Turan seems to be the only player who can make a difference on the big stage. Fatih Terim, who is working as the Turkish national coach for the third time in his career, experiments with a variety of systems, but mostly uses 4-2-3-1 and 4-3-1-2 shapes, although the devil is in the details.

Despite having a big group of talents, Arda Turan seems to be the only player who can make a difference on the big stage. Fatih Terim, who is working as the Turkish national coach for the third time in his career, experiments with a variety of systems, but mostly uses 4-2-3-1 and 4-3-1-2 shapes, although the devil is in the details.

Both Turan and Çalhanoğlu are very versatile, and therefore have played different positions. The former mostly starts on the left side and moves from there to the middle as often as possible. Even in deeper half-spaces, Turan shows his presence and is involved in the build-up play.

Speaking of which, Turkey emphasise the wing zones when making attacking plays. Even though their full-backs are prone to losing the ball easily, both often get involved in the early build-up play. The team are great at detecting and penetrating open zones when moving forward. Quick cut-backs and accurate lay-off passes usually dominate their plays, with Turan being the anchor in the middle. He tries to keep contact with all the other central players while impelling ball circulation.

Up front, Turkey have fluidly moving strikers with average abilities as far as breakthroughs are concerned. Moreover, their wingers allow themselves to be led to the outer zones, walking into isolation traps.

In the pressing department, Turkey use a customary 4-4-2 or 4-4-1-1 formation, with one centre-midfielder often moving forward to control higher zones, while shutting down passing lanes in the middle. Usually, one centre-midfielder is used as a man-marker, while the other patrols through the central zones.

When the opposing team bypass Turkey’s first lines, the Ay Yıldızlılar start to backtrack which ends up in sitting deep in the own penalty box. Especially the attacking wingers chase back at speed so that they can become part of the back line. Otherwise, a full-back could leave the gap between him and the centre-back next to him open when he thinks he has to move closer to opposing winger. Even though Terim’s defensive system relies on simplicity, his players overreact on some occasions, which then causes exposed zones and disorganisation.

Overall, Turkey are able to beat any opponent at any time. However, it is also possible that they lose to mediocre competition by a wide margin.

Key element: a team rallied around one star player

***

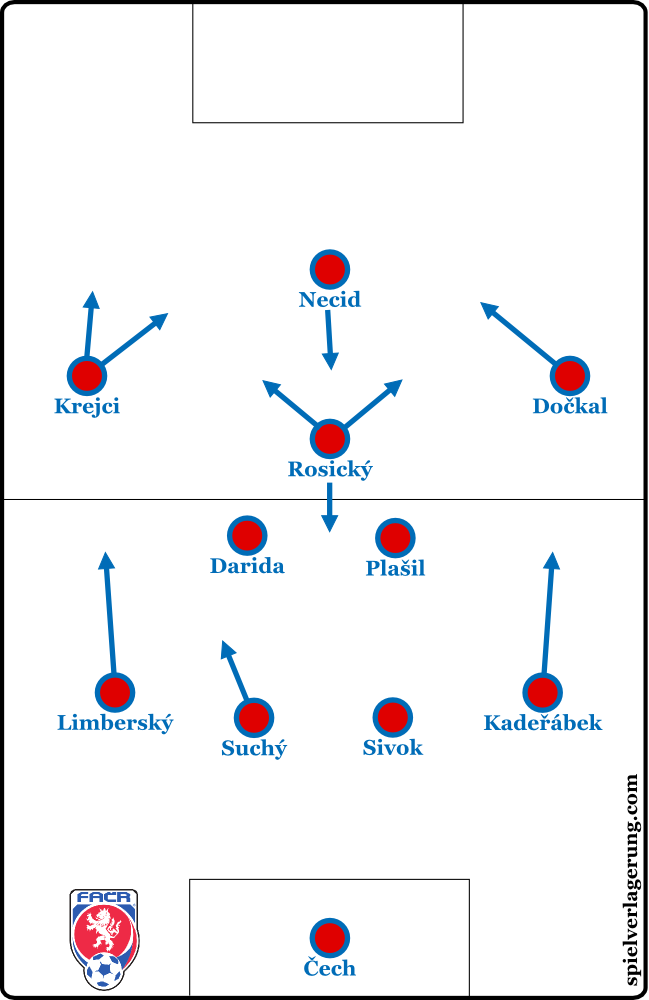

While Turkey finished only third in the Euro qualifying group A, the Czech Republic won that particular group. Both teams will meet again in France.

The Czech talent pool is not as deep as the ones from their opponents. Nevertheless, a few players have shown potential and could drag the team to satisfying results. It is by no means comparable to the situation in 2004, though.

Pavel Vrba, who was named Czech Coach of the Year for five consecutive years between 2010 and 2014 when he was in charge at Viktoria Plzeň, places reliance upon a standard 4-2-3-1 system. In the early build-up play, a number six player drops between the centre-backs to outnumber the opposing team that usually pressures the back line with two players. Plus, both centre-backs, but in particular the rather agile Marek Suchý, have the opportunity to push through the half-spaces. At times they are forced to do so, as the vertical passing lanes are blocked due to a lack of presence shown by the midfielders.

Pavel Vrba, who was named Czech Coach of the Year for five consecutive years between 2010 and 2014 when he was in charge at Viktoria Plzeň, places reliance upon a standard 4-2-3-1 system. In the early build-up play, a number six player drops between the centre-backs to outnumber the opposing team that usually pressures the back line with two players. Plus, both centre-backs, but in particular the rather agile Marek Suchý, have the opportunity to push through the half-spaces. At times they are forced to do so, as the vertical passing lanes are blocked due to a lack of presence shown by the midfielders.

When both centre-midfielders decide to stay in midfield, they usually stand right on the outside of the opponent’s first pressing line. Moreover, early in the build-up play the Czech Republic involve their full-backs who then try to find open men in the diagonal slots.

Especially Tomáš Rosický, when playing as a number ten player, offers a constant passing option for the team-mates behind him. The Arsenal midfielder is an effective playmaker as long as the tactical setting favours his strengths. Alternatively, Jaroslav Plašil could play in the middle and provide connection.

The centre-backs occasionally play risky passes right to the centre-forward who lays off the ball afterwards. Once they reach the opposing half, several problems start to emerge. For instance, Vladimír Darida disappears when he is actually asked to push forward and pick up the ball. Constant positional switches within the attack can help to confuse the opposing defence. The centre-forward’s relapsing movement can also lead to an opposing man-marker chasing after the striker, which ultimately causes gaps near the offside line.

These patterns seem more promising than simple wing attacks, in which the outside player can be isolated fairly easily. On a downside, the interplay between a brawny striker like Tomáš Necid and a fluidly moving number ten player tends to become predictable after a while. Nevertheless, Vrba only has a limited choice of weapons, and he tries to make the most of it.

On the other side of the ball, their pressing is as textbook and as boring as it gets. In a 4-4-2 shape, the two players up front cover the opposing full-backs. Czech’s wingers cling to the opposing full-backs. In the second phase of their pressing, they change the formation into a 4-4-1-1, showing consistent passivity in terms of how they defend the own third.

Consequently, the Czech Republic are prone to through balls that hit them right in the gaps of their back line. This vulnerability is also boosted by the fact that they cannot shut down the central zones after turning over the ball.

As if that was not enough, their defence get beaten in one-on-ones easily and opponents can hit them with diagonal lobbed passes due to Czech’s passive behaviour off the ball and the lack of diagonal defensive lines.

It is hard to imagine that this team will make a deep run at the Euro tournament. Head coach Vrba and his side are in an early stage of development, but should not use this circumstance as an excuse.

Key element: defensive and attacking football 101, short of creativity and speciality

Group E

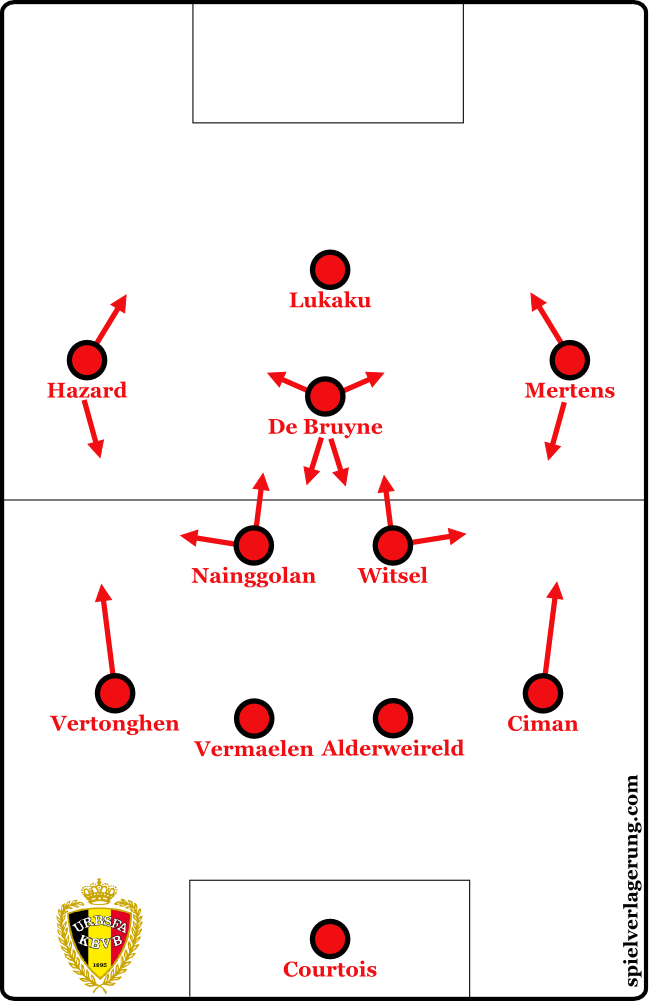

They have been the hottest thing in national-team football for quite some time. And that is not because of their jersey colour. Belgium gather some of the most promising players in all of football. But this does not mean that the Red Devils will automatically win the tournament. It does not even mean they will make a deep run. Expectations can become a burden. Mediocre tactics can become a self-created obstacle.

Let us start with their defence. Belgium are nothing like a dominant side, striving to determine the progress of a game universally. Rather, they defend in a passive 4-4-2 or 4-2-3-1 shape, where the players up front only sometimes attack the opposing centre-backs to get the ball back as soon as possible. Usually, a few man-to-man markings cause some holes across the middle. Both wingers more or less do not have to attend to defensive duties, which often leaves the full-backs exposed. Considering the space they have to cover and taking the lack of support into account, both full-backs could run right into a disaster if the opposing teams are able to capitalise from that structural weak spot.

Let us start with their defence. Belgium are nothing like a dominant side, striving to determine the progress of a game universally. Rather, they defend in a passive 4-4-2 or 4-2-3-1 shape, where the players up front only sometimes attack the opposing centre-backs to get the ball back as soon as possible. Usually, a few man-to-man markings cause some holes across the middle. Both wingers more or less do not have to attend to defensive duties, which often leaves the full-backs exposed. Considering the space they have to cover and taking the lack of support into account, both full-backs could run right into a disaster if the opposing teams are able to capitalise from that structural weak spot.

The strength of Marc Wilmots’ side clearly lies in the accumulation of talented attacking players, although constantly involving these talents in plays is not an easy task. When building up, Belgium’s centre-backs sometimes go back to play long balls that are not effective at all. It seems to be more surprising when Radja Nainggolan and other centre-midfielders pick up the ball and initiate short combination plays with Kevin De Bruyne.

Speaking of the Manchester City star, he knows that he cannot stand near the offside line and wait for his team-mates to move the ball forward. His fluid movement, paired with a centre-forward roaming through the half-spaces to play lay-off passes towards the side line, is crucial to Belgium’s effectiveness in attack. Entering the last third, their agile wingers, such as Eden Hazard, are normally anxious to dribble diagonally, coming at the opposing back line, or the rest of the team set up through balls picked up behind the line by those wingers.

Due to the a deep-lying centre-back duo, Belgium attempt to stretch the field, though this leaves the zones in front of their central defenders open, which makes them vulnerable when turning the ball over near the halfway line. This is not the most worrying issue, however.

When controlling a match against a deep-sitting opponent, Belgium’s formation too often appears shaped like a semicircle, with little to no presence at all in between the opposing lines. The lack of a sophisticated possession game becomes even more severe considering the perception of the Red Devils. They are now the favourites against a vast majority of teams.

Instead of enhancing their attacking structure or solving their defensive vulnerability on the flanks, individualism is at the forefront of their thinking. Of course, if you have a dozen of highly gifted players in attack, it is not completely wrong to focus on their strengths, but that should not lead to the non-existence of tactical synergies.

In Belgium’s case, it causes a deficiency in terms of passing flow, which means that usually their attacking plays are a sequence of dribbles connected by a few passes, destroying any kind of dynamism. When advancing forward at speed and finding open spots in opposing territory, effective build-up patterns arise automatically.

To end on a positive note, Belgium possess a variety of intelligent players and playmakers with a great range on the field, which can cause some sort of self-organisation within the micro-cosmos. Add various individual qualities and a huge selection of player types to this, and you get a contender for the title.

Key element: football as a players game under Wilmots’ guidance

***

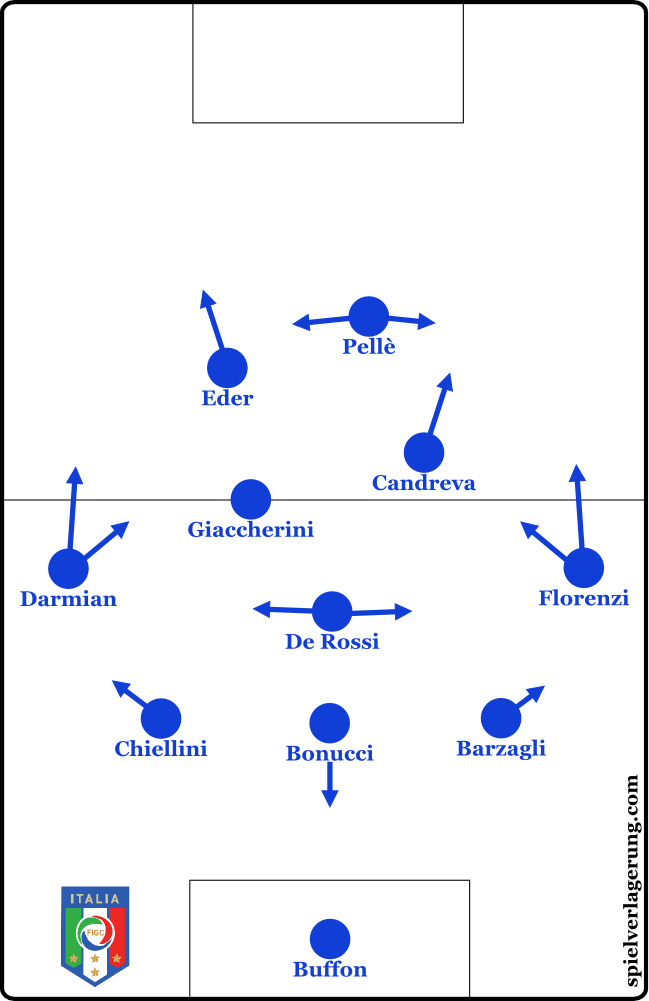

The tireless Azzurri are more or less favourites for every tournament they are part of. One cannot count out the resilience of an Italy national team that is by no means packed with the most skilled players in Europe. Nevertheless, head coach Antonio Conte has the freedom to use different formations, to try various tactical set-ups and to contrive several concepts, so that Italy are ready for every opponent to come.

Normally, it depends on the availability of the three Juventus defenders, Giorgio Chiellini, Leonardo Bonucci and Andrea Barzagli, whether Conte plays a back three or not. But there are more factors that play a role. Therefore, a 4-4-2 shape is also possible to be used, at least partly, during the tournament. Overall, Italy’s tactical base enables flexibility. They can be dominant or defensive and passive. They can press aggressively or wait cautiously.

Normally, it depends on the availability of the three Juventus defenders, Giorgio Chiellini, Leonardo Bonucci and Andrea Barzagli, whether Conte plays a back three or not. But there are more factors that play a role. Therefore, a 4-4-2 shape is also possible to be used, at least partly, during the tournament. Overall, Italy’s tactical base enables flexibility. They can be dominant or defensive and passive. They can press aggressively or wait cautiously.

In build-up plays, the Azzurri surprisingly draw on a great amount of long balls out of the back line towards the centre-forwards, or medium-range diagonal balls reach the advancing wingers after a short period of circulating the ball through deeper zones. When using a small-ball strategy, wingers and centre-midfielders stand closely together to provide connections, but it is hard to move the ball forward escaping these narrow zones. And even if they enter the final third, the coordination among the centre-forwards is a far cry from perfect.

The difference between a 4-4-2 build-up and a 3-5-2/3-4-2-1 build-up is that, when using a back four, both centre-backs usually travel to the sideline, while both centre-midfielders fill the central zones, without dropping between the defenders.

In a 3-5-2/3-4-2-1, however, the central defender is positioned deeper than his team-mates at the back, stretching the field and therefore intending to disentangle the situation in the middle third. The lone centre-midfielder is usually covered by opposing defenders, which allows the centre-backs to play horizontal passes through backfield. This forces the opposing formation to keep moving and could offer Italy openings in the half-spaces to get both number eight players involved.

If the opponents are able to negate these kind of tricks, at least one wing-back usually drops back and positions himself in front of the opposing pressing block to offer an additional passing option, albeit this often leads to knocking the ball forward because of the lack of open men in the middle of the park or because of the immediate pressure the wing-back feels.

On the other side of the ball, Italy can vary their pressing intensity. In a 4-4-2 shape, both forwards normally block the opposing centre-backs, while the midfielders apply a man-marking scheme in the zones behind and the wingers occasionally pressure the opposing number six players. Italy’s counter-pressing, however, looks clumsy most of the time, which magnifies their vulnerability after turnovers. They need time to find the appropriate formation in defensive transition while offering holes in the centre that help the opponents move the ball across the middle fairly easily.

Playing a 3-5-2/3-4-2-1 system that includes a holding midfielder behind the more attacking players and riskily behaving wing-backs, the six Italians up front can circle around the ball-carrier and pressure the opponent’s build-up play.

To address a few issues the Italian team has yet to solve: Italy use way too many long balls. This limits Bonucci who cannot provide smooth passing plays as he normally does and which would be necessary to make the team more unpredictable. Moreover, a great amount of rash clearances causes busy matches with many changes of possession. Italy need to force their preferred playing rhythm upon the opponents, though. Conte has the depth in his roster and the variety of player types to do that.

Key element: experience couple with wilingness

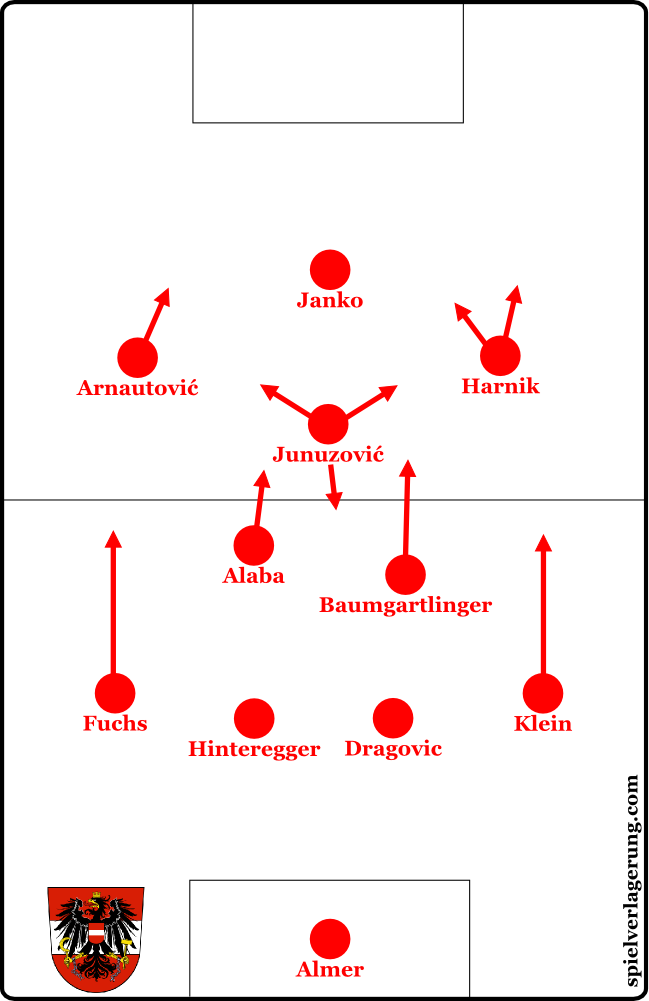

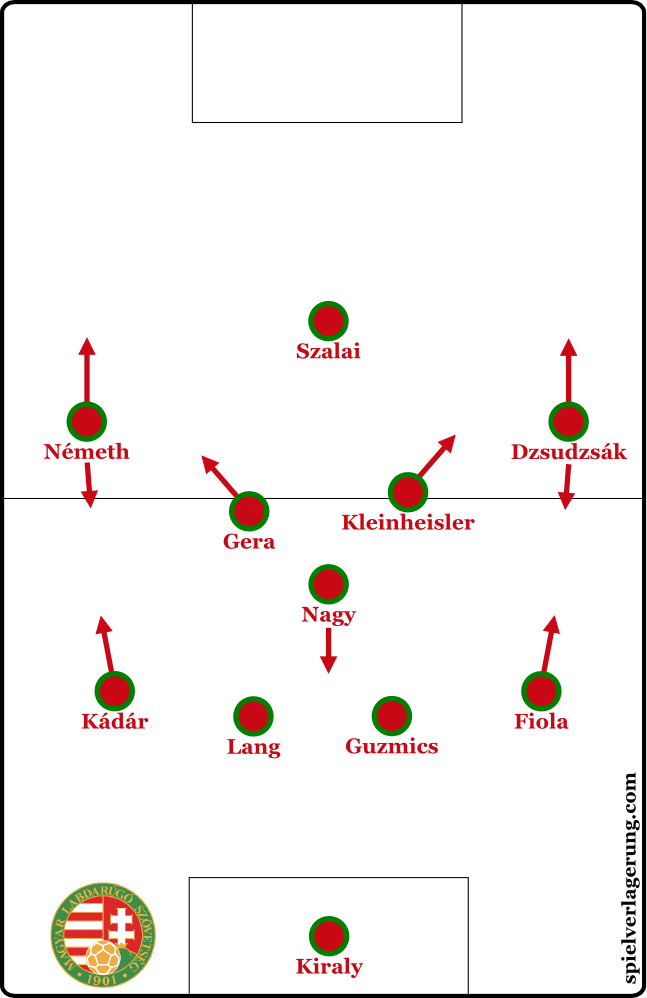

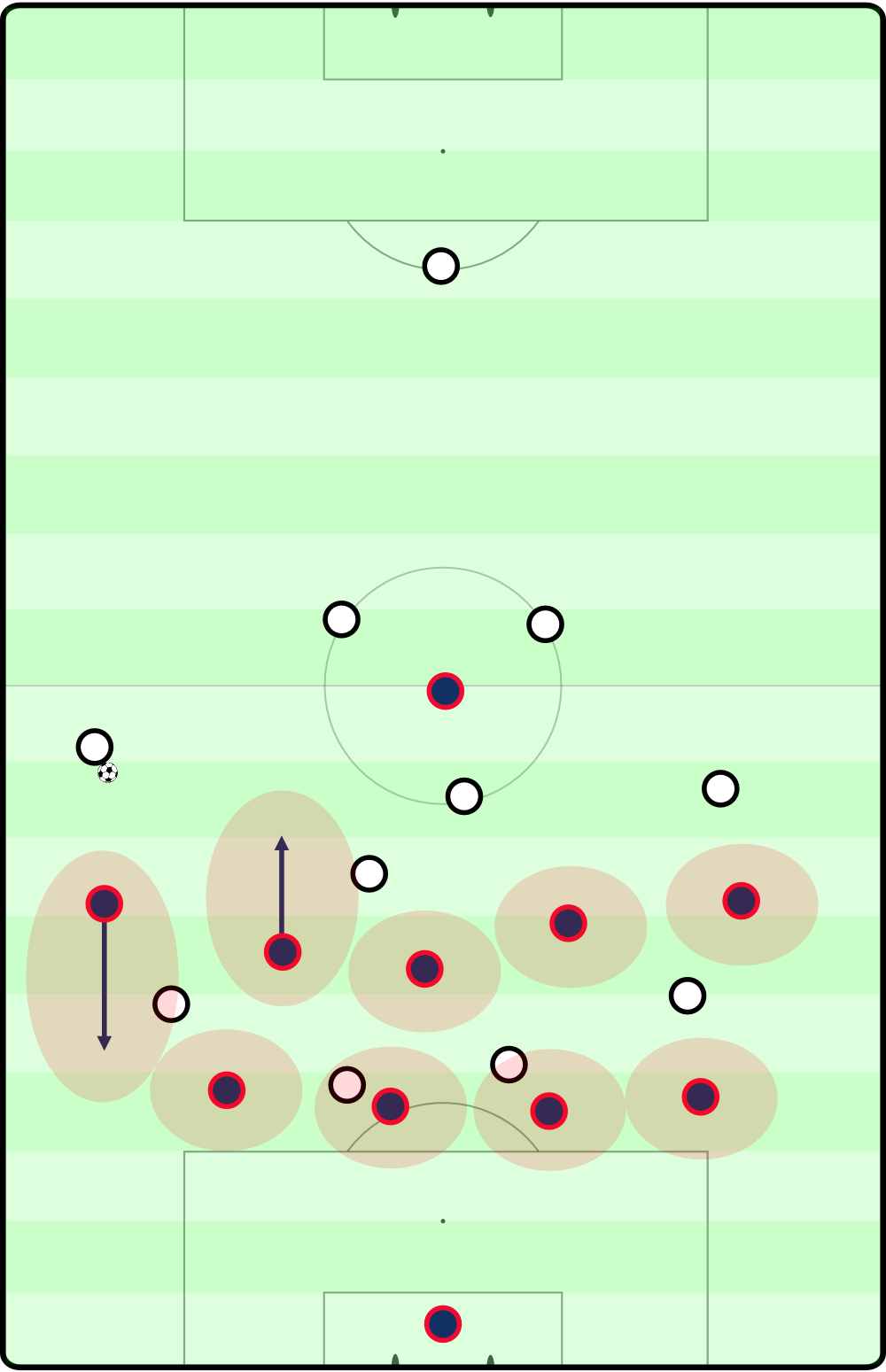

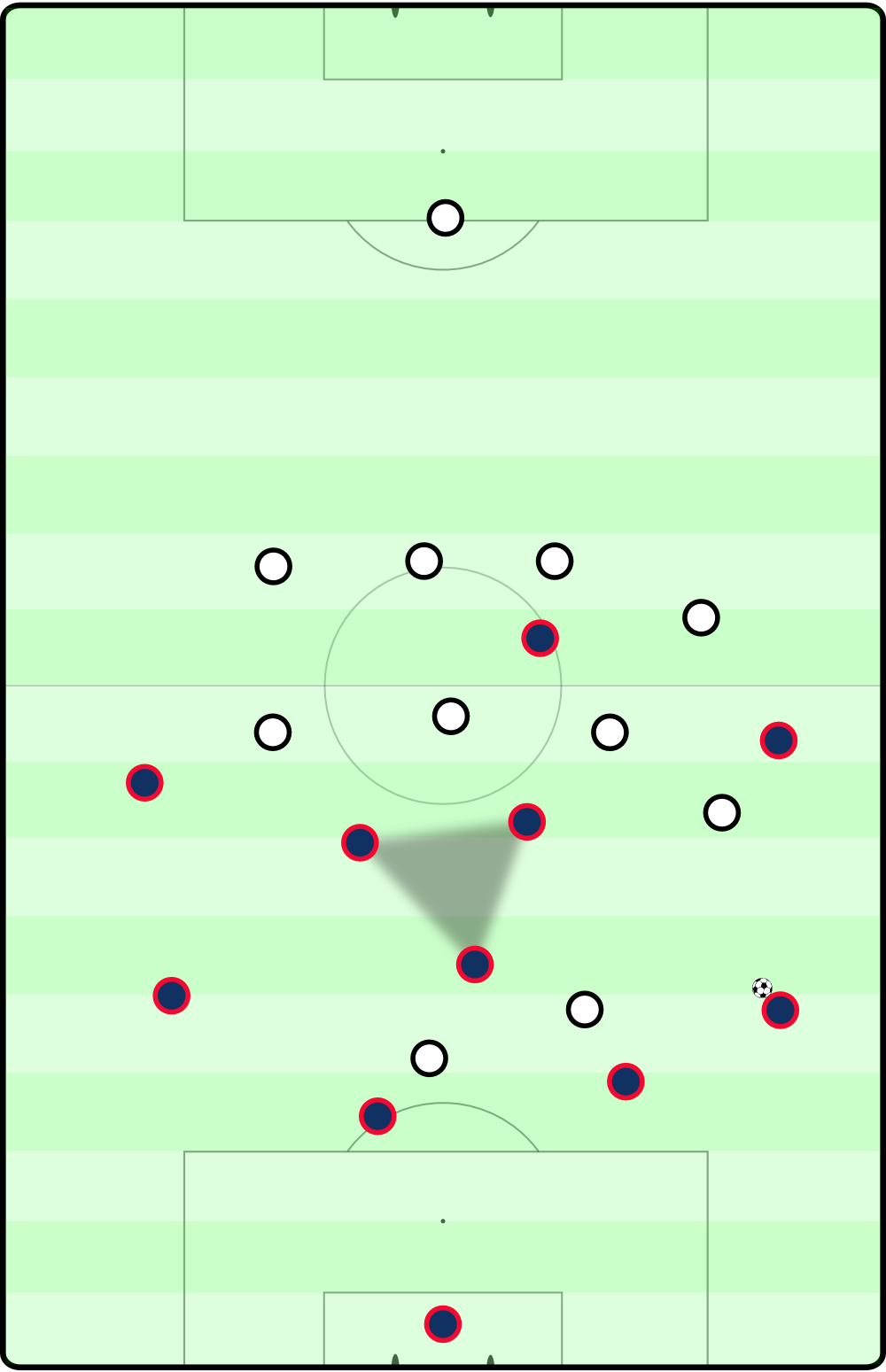

***