Essay: Escape – MX

A few thoughts and reflections on the analysis bubble.

Humans want to understand. A fundamental need of our species eventually developed a concept for the desire to understand and to derive understanding: analysis. Carried through the centuries and applied primarily in literature, this drive increasingly found its way into the comparative physical activity of humans-sport. It fascinates hundreds of thousands of people every weekend; the urge to comprehend the logic – even where there is none – behind the results has become ever more omnipresent. Yet analysis existed long before people fully understood what analysis was – analyzing no longer becomes analysis simply because one is aware of doing it. Tracing the philosophical origins of analysis, pure analysis is merely a subform of communication: communicating by breaking down a whole into parts.

If we understand analysis as part of a larger communication context, it is hardly surprising that analytical formats in Europe developed primarily through blogs and digital platforms – parallel to the ongoing technologization of the world. Analysis has always existed, but only with the internet did it gain new relevance: communication could, for the first time, reach a potentially unlimited audience permanently. This explains an apparent contradiction of its origins: analysis exists continuously, yet it is always dependent on its recipients. Without an audience, it has no effect. In the words of Niklas Luhmann, communication does not arise from mere sending, but from understanding on the part of the receiver. Analysis is therefore not an isolated act, but an interactive process.

In the age of social media, however, this dependence increasingly leads to a dead end. Highly complex matters are expected to be made understandable, consumable, and entertaining within thirty seconds. Paradoxically, social media produces more recipients than ever – and simultaneously a structural scarcity of attention. Georg Franck refers to this as the “attention economy,” in which visibility, rather than truth or depth, becomes the central currency. For a long time, analysis was a dialogical process: presenting, structuring, weighing – a reciprocal interplay between sender and receiver, reliant on resonance and reflection. Jürgen Habermas’ concept of communicative action captures exactly this: understanding emerges where arguments are given time and space. In short-form formats, communication continues- often with enormous reach- but the channels through which it occurs have shifted.

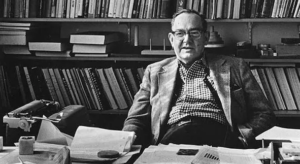

Herbert A. Simon

“A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.” – Herbert A. Simon

Analysis increasingly degenerates into a tool for tabloid-style exaggeration. Headlines such as “THE NEW TACTIC,” “THE BEST PRESSING IN THE WORLD,” or “THIS IS MODERN FOOTBALL” suggest analysis but primarily follow market logic. Analyses are linguistically amplified as if they must be sold: the newest product, the best of its kind, faster, higher, further. Football as a consumer product is established – but now even the idyllic backyard of analysis? Marshall McLuhan’s famous dictum, “The medium is the message,” becomes particularly tangible here: the format determines not only the form, but increasingly also the content of analysis itself. The task is to reclaim analysis as a pursuit of understanding and curb its reduction to a consumable, attention-driven product – perhaps the challenge of the modern era is not to reinvent analysis, but to restore time, depth, and dialogical capacity to it.

To continue the metaphor of the idyllic backyard: analysis is increasingly turning into a bustling city. Here a street vendor, there a shop – no, I don’t want to buy anything. Help, where have I ended up? Everything crowded, everyone stressed, everyone caught in the rush of striving, of wanting. I just want the idyll: a coffee, some calm, a deep conversation. But the idyll is dead. Perhaps, as an analyst, one sometimes feels a certain emptiness – a metropolitan melancholy – the emptiness of overstimulated impersonality.

“The metropolitan is compelled by the economy of money exchange to a precision and objectivity that deprives personal life of its warmth.” – Georg Simmel, The Metropolises and the Intellectual Life, 1903

But let us zoom out again: I often experience this feeling on “X” or YouTube. There is an abundance of information, often highlighted for attention. Yet more information on complex topics does not automatically lead to more knowledge; it generates noise – a noise I described earlier in the metaphor. This constant noise simultaneously depletes the already scarce resource of attention and creates a perpetual stimulus environment, leading to a lack of contextualization and interpretation, while leaving many exhausted-another tactic video, another tweet, another reel on the best pressing? Phew – this “phew” is what science calls fragmented cognition. Algorithms naturally amplify extremes-even in sports: outrage, “ALL-CAPS HEADLINES,” or promotion drive engagement.

This critique is not aimed at users or analysts; we are all trapped in a system with incentive structures. Nevertheless, I want to draw attention to the growing bubbleization and ideological polarization of the analysis scene, amplified by extremes and a lack of contextualization. Quick accessibility and democratization lead to information, to knowledge, but this abundance also produces a depletion of theory and balance. We experience a pseudo – plurality in sport, an implied logic in the game that does not exist, manifested by algorithms – through likes and views.

A concrete example: relationism. A fascinating topic, scarcely explored-yet the mere word triggers algorithmic attention so heavily that it is used excessively, reducing it to a black-and-white concept and establishing a dogma, rather than allowing proper theoretical discussion. How do we get out of this situation? Everyone has taste, everyone has preferences – yes, everyone has their dogmas. We are human – accept it. As René Marić once said, dogmas can be dissolved by connecting them, by allowing different ideas to meet. Or as Jamie Hamilton puts it: perceive analysis as aesthetics. If we understand football as aesthetics, then football becomes art – but what is art? Art is the undefinable. And if we accept football as something without logic, we may at least free ourselves from established regimens of thinking and dogma. Don’t let yourselves be confined – feel the aesthetics.

“We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.” – Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 1981

If we turn to history, literary philosophy shows us that even the concept of freedom divides opinion – does freedom enable analysis, or does it simply reinforce the status quo and thereby prevent true analysis? Perhaps, however, this is not the real question. Maybe it is not about freedom versus non-freedom, but about whether we understand logic as the opposite of freedom. Logicimplies binary outcomes – true or false, right or wrong – and this stands in tension with the ‘spirit of play’. Play has rules and objectives, yet within the act of playing there are no universal truths. The growing sense of uniformity and rehearsal – the impression that everyone plays in similar ways – often creates the feeling that the game follows the rules of a single, universal logic, as if logic determines play rather than play shaping logic.

aesthetic.

My concern is less about what is objectively right or wrong in football, and more about how we, as analysts and coaches, sometimes present our ideas as universal truths. By doing so, we implicitly suggest that there exists a pure logic within the game – a logic that may not fundamentally exist. I would argue that sport exists primarily to evoke emotions in those who play and those who watch – an experience that can be understood through aesthetics, where art becomes a counterpoint to logic, as Tolstoy suggested. This challenges the belief that results or success should stand above everything else and dictate our styles of play.

If there is no single ‘true’ way to play, then there can also be no single true analysis that fully dissects it into definitive parts. That is why we must give space to the diffuse edges – even at the risk of weakening clarity or precision in our explanations – and accept that not everything can be clearly identified or categorized, because pure logic does not exist here. Yet I firmly believe that by allowing more room for uncertainty and ambiguity within the game, we open ourselves to entirely new worlds of understanding. And precisely for this reason, it is all the more important to ask ourselves who we are-and what we want to be as analysts. We must no longer divide ourselves into “us” and “them,” but understand ourselves as a shared form of football observer. Hannah Arendt describes thinking as an activity that only unfolds in exchange, as something that emerges in the “in-between” of people. Analysis, therefore, is not a possession, but a process. We need to dare more again: recognize our own (natural!) weaknesses in reasoning, disclose our personal assumptions, and discuss more honestly with one another. Know more of what we do not know and never will.

For this reason, I am skeptical of sharply distinguishing between universally trained and didactically trained analysts – or of job advertisements favoring only one type. Pierre Bourdieu shows that fields tend to stabilize through differentiation rather than understanding; separation becomes a social marker rather than a question of quality. Class war! Is that really what we want? Pitting the professionalization of sport against an open culture? This runs all the way from coach education to analyst circles: those who were never professionals are excluded. Those who do not meet the standards in general education also do not meet the standards in football. It is a coupling of market logic with football – and we need a return to open football, even if this openness, in some places, requires a degree of self-criticism that is uncomfortable for some decision maker. Breaking out of established logics also means accepting that logic cannot be predetermined.

For this reason, I am skeptical of sharply distinguishing between universally trained and didactically trained analysts – or of job advertisements favoring only one type. Pierre Bourdieu shows that fields tend to stabilize through differentiation rather than understanding; separation becomes a social marker rather than a question of quality. Class war! Is that really what we want? Pitting the professionalization of sport against an open culture? This runs all the way from coach education to analyst circles: those who were never professionals are excluded. Those who do not meet the standards in general education also do not meet the standards in football. It is a coupling of market logic with football – and we need a return to open football, even if this openness, in some places, requires a degree of self-criticism that is uncomfortable for some decision maker. Breaking out of established logics also means accepting that logic cannot be predetermined.

“Technology is never neutral; it always changes the conditions under which knowledge is recognized.” – Neil Postman, Technopoly, 1992

Attempts to standardize analysis this way lead to the imposition of linear thinking – a workflowization of analysis. The constant noise of information overload reinforces this effect. Increasingly, I observe a communicatively insulated bubble of club-based analysts, where external exchange is hardly desired. Yet the core of analysis is forgotten: “Thinking without communication is empty,” writes Jürgen Habermas-knowledge emerges in dialogue. Analysis thrives on joint dissection, on contradiction, and on critical (self-) questioning.

This text is not a judgment of the scene. Rather, it is an expression of unease-a self-reflective judgment. I, too, have long allowed myself to be guided by factions, by the pursuit of jobs, by the pursuit of attention, and I became dependent on it. Only when I became aware of this and adopted a more didactic path – without a goal beyond curiosity about the game – did new worlds of football open up to me. A curiosity expressed not in truths, but in provisional knowledge; in perspectives rather than dogmas; in theory as a tool rather than a label. Perhaps our strength should not lie in being faster, louder, or bigger. Perhaps it lies in withstanding the noise of the digital age. Where analysis no longer allows contradiction, it ends. But it also ends where analysis becomes mere consumption. But to end the text on a positive note – at the same time, there are more opportunities than ever before, more tactical cameras than ever, and more games to analyze than ever.

It’s in our hands what we do with it.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen