Mjällby AIF: An Analysis of the Swedish Champions’ Possession Play – MH

Mjällby AIF are Swedish champions. For the first time in their history, the small fishing village of 1,300 inhabitants has managed to outperform the competition from the bigger cities, helped by an exceptional brand of attacking football.

“Europe’s surprise team comes from a tiny fishing village on Sweden’s southern coast. The sporting director is a farmer. The coach is a former school principal. The story of Mjällby AIF: a miracle?“ – Dorfklub Mjällby AIF mischt Schweden auf: Einsame Spitze – 11FREUNDE

”A unique tale in football: In Sweden, Mjällby AIF from a small fishing village and with little money are celebrating the championship, thanks in part to the football doctor.“ – Mjällby AIF: Der Meister aus dem Fischerdorf | DIE ZEIT

“Not even ten years ago, the village club stood on the brink of collapse. This weekend, Mjällby could become the smallest place ever to produce a European champion.“ – Mjällby könnte Meister werden: Bekommt Schweden einen Sensationsmeister – 11FREUNDE

“Always follow the beach, then turn left at the campsite. Anyone heading for the stadium of league leaders Mjällby AIF in the Swedish fishing village of Hällevik won’t struggle to find it. ‘We play where the world ends and the sea begins’ is how the club describes the route to their home ground that bears the lovely name Strandvallen.“ – Fußball: Warum der Dorfklub Mjällby AIF Meister in Schweden werden könnte | sportschau.de

“For Mjällby’s opponents, a trip to the far south of Sweden feels like a journey to the Earth’s end. ‘When teams come on here on the bus they drive and drive, through the farms, past the fishing harbours,’ says Hasse Larsson. ‘They keep driving and then, when they can’t drive any further, they find our stadium.’” – Mjällby making minor miracles in an extraordinary Swedish football story | European club football | The Guardian

“’It’s 1,500 inhabitants in the village where they play, and you’re just flabbergasted when you see this elite football going on,’ Erik Hadzic – a reporter for TV4 Fotbollskanalen, who has covered the team for the last five years – tells CNN Sports. ‘Mjällby winning the Swedish championship is arguably the biggest sensation in the history of the Swedish league.’ The tiny team from Hällevik has not just won the league, either. It has absolutely blown away the competition.” – Mjällby AIF: How a tiny Swedish team achieved one of the biggest ever shocks in European soccer | CNN

Mjällby AIF have managed to appear across virtually every media outlet. By winning the Swedish championship, the small village club now enter Champions League qualifying, giving them the chance to measure themselves against the very biggest. This article aims to explain the type of football that led Mjällby to the Swedish title. Since their possession game stands out, the analysis focuses exclusively on this aspect.

Assistant coach Dr Karl Marius Aksum is regarded as the main architect of Mjällby’s attacking football. In his doctoral thesis, he wrote about visual perception and more specifically about scanning in professional footballers. Scanning is defined there as “all head movements away from the ball with the intention of gathering performance related information from one’s surroundings.” Aksum uses Gibson’s ecological theory of perception to show why scanning matters.

This theory emphasises that perception is inseparable from action possibilities. Humans do not only perceive objects, but above all the possibilities for action that an environment offers them, known as affordances. Translated into a football context: only when a player recognises the relevant elements of a situation, such as an opponent’s position, a passing option or a teammate’s run, can he make the appropriate decision. If such action possibilities remain unnoticed due to poor scanning, they will not be used.

Unlike most previous research on scanning in football, Aksum equipped players with specialised sports goggles using eye tracking technology, collecting data during full sided eleven versus eleven matches. These game realistic data allowed him to obtain results that reflect actual match conditions far more closely. The findings show that an average scan lasts roughly 0.40 seconds, although the most common scan duration is substantially shorter at 0.26 seconds. Moreover, 90.3 percent of all scans are shorter than 0.66 seconds. Fixations occur only rarely, as just 2.3 percent of scans contain a fixation and these last significantly longer than regular scans.

It is also highlighted that players do not process details such as faces in this short time frame, but mainly detect movements and colours. For training practice, this means that drills requiring prolonged or detailed information gathering during scanning lack match realism. In game situations, the brief duration of scans only allows players to pick up fundamental spatial and colour based cues. I have linked the dissertation here, titled ”Visual Perception in Elite Football“. The topic of scanning will also be examined in greater detail in another future article, possibly in a slightly different format.

Before Aksum’s arrival two years ago, Mjällby struggled heavily to turn matches around after falling behind. The club subsequently advertised a position aimed at solving this issue and succeeded. Karl Marius Aksum has since been appointed head coach for the 2026 season, taking over from the highly capable leader Anders Torstensson, who has moved into the role of technical director. Mjällby are now able to play through high pressing opponents as well as create chances against deep defensive blocks.

To conduct this analysis, I examined six different matches. Since six games are a limited sample and could skew certain aspects of the possession game, I list them here: Mjällby 4-1 Degerfors, AIK 2-1 Mjällby, Norrköpping 1-1 Mjällby, Mjällby 2-0 AIK, Malmö 1-3 Mjällby, Mjällby 2-0 Elfsborg.

The selection of matches was not made by me but by the aforementioned Karl Marius Aksum. I am therefore confident that these six fixtures cover the majority of Mjällby’s overall game. Many thanks once again for the openness. Obtaining suitable video material from the Allsvenskan turned out to be far more difficult than expected.

A First Look at Mjällby: Players, Structure and Basic Principles

Mjällby generally operate in a nominal 1-3-2-4-1 structure. Goalkeeper Törnqvist is exceptionally strong with the ball at his feet. He is therefore consistently integrated into Mjällby’s build-up through a goalkeeper line. When Mjällby build with a back four, he can function as either the right or the left centre back. He very often looks for line breaking passes through the middle. His qualities have also caught the attention of Como, currently fifth in Serie A as of December 2025, who have already signed him. Como under coach Cesc Fàbregas also repeatedly build short with the goalkeeper involved.

The back three usually consists of right centre back Iqbal, central centre back Norén and left centre back Pettersson. Iqbal in particular pushed higher in certain matches during the build-up phase. Despite standing 1.92 metres tall, he is technically excellent and can therefore also take on the slightly higher and wider full back role of a back four depending on the opponent. Against deep defensive blocks, both outside centre backs of the back three are actively involved in the attacking phase. More on this later.

The wing backs in the five man line are Johansson on the right and Stroud on the left. Johansson is one of the more experienced players at 28 and among those with the most minutes. He frequently provides depth with runs beyond the opposition back line, combining pace with physical strength. He is also the first Mjällby player ever to be capped for the Swedish national team. Left wing back Stroud, on the other hand, was deployed centrally as a number ten towards the end of the season. Left wing back Stavitski is considered the primary replacement. The wing backs can operate at virtually any height and are used asymmetrically depending on the opponent. They often provide width when Mjällby attack with two wide players.

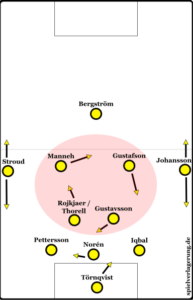

The centre of Mjällby’s structure is something of a holy grail in their build-up. In the nominal 1-3-2-4-1, it consists of two tens and two sixes, but only nominally. To gain a clearer understanding of Mjällby’s build-up, I eventually began to describe the structures as for example 1-3-diamond-w2-d1 (w=wide, d=deep), 4-trapezoid-1-w2, 1-3-Y-2-d1 and so on. By isolating the centre as a separate perspective, the different central configurations become particularly visible. Depending on build-up height and the opponent, Mjällby vary the number and positioning of their tens, eights and sixes. What stays constant is that there are always four central players. The w2 notation (w=wide) refers to the wing backs, though not perfectly accurate since they can also abandon the wide corridor.

Six Gustavsson is essentially always part of the central unit. He plays from the deepest central role, close to the defensive line, and is the team’s captain. Until his departure in the summer, the technically gifted six or eight Rojkjaer was also a constant. He was replaced depending on the opponent by various players, such as eight Thorell, left wing back Stroud or ten Kjaer. On the right side as a ten or eight, Gustafson (not to be confused with six Gustavsson) usually features.

The left or central ten Manneh deserves special mention, as he brings exceptional qualities. He is explosive, very fast and excellent when driving forward on the dribble. Alongside wing back Johansson, Manneh regularly provides depth or beats opponents to create superiority. He is already being linked with clubs from the top two divisions in England. His output is all the more remarkable considering that Mjällby as a team rank lowest in the league for dribbles. Dribbling simply is not a frequently used attacking tool for them, yet Manneh consistently stands out.

Up front, the lone striker is usually the experienced Bergström. He is used as a target and is frequently the focal point in the build-up, laying balls off for advancing central players. On aerial deliveries, he is the primary target.

Mjällby’s possession game is not the only factor behind the Swedish champions’ success. Naturally, their play also includes several other interesting elements, such as ball-near overloads during opposition throw-ins or a strong central focus in their pressing. In attack, they also make frequent use of long throw-ins into the box, and set pieces play an important role. The possession game, however, is one of the most intriguing in Europe, as it operates with completely different structures and patterns than usual. Accordingly, the focus of this team analysis lies on this aspect.

Build-Up Play Against High Pressing and on Goal Kicks

Mjällby’s build-up structure varies significantly depending on the opponent’s pressing approach. This naturally creates challenges for the analysis. While there are overarching principles, these do not lead to fixed or repetitive patterns. On the contrary, Mjällby’s build-up looks particularly different when facing a high press or full man marking on goal kicks. The main differences arise from the structures and target zones Mjällby uses to exploit specific weaknesses in the opponent’s pressing. For this reason, the following analysis of the build-up will be broken down by match.

Mjällby – Degerfors (4–1), 27 April 2025

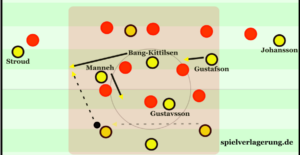

Mjällby started, as usual, from a 3-2-4-1. There was, however, an important detail in the central area. With Bang-Kittilsen and Manneh, two natural number 10s were fielded, meaning that Gustafson – another 10/8 profile – occupied the nominal holding midfielder role. Depending on the phase of play, Mjällby could therefore rely on three number 10s and build from a one-three structure in midfield.

Degerfors pressed in a 5-4-1, shifting into a 5-2-3 during the high press. As is common in the Swedish league, they avoided full man marking and instead maintained a plus-one or plus-two advantage in the last line. Consequently, Degerfors did not press goalkeeper Törnqvist directly, but triggered their press after the first pass. Because both Degerfors midfielders pushed high to avoid being outnumbered centrally, a large space opened between their midfield and defensive line. In addition, the half backs in the Degerfors back three did not step forward into this space but held their position on the last line to provide cover.

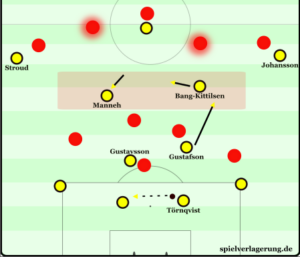

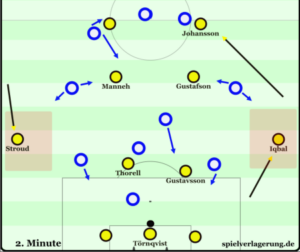

Mjällby build up from a 4-trapezoid-3 structure and look to transition into three number tens in order to exploit the large space between the lines in Degerfors’ 5-4-1 pressing shape.

Mjällby’s obvious objective was therefore to exploit this large space between the lines. Using the goalkeeper as an extra player and with three number 10s available, they were well equipped to access and run through that zone. The starting point for the build-up against Degerfors was the 4-trapezoid-3. Fullbacks Stroud and Johansson pushed up to the level of striker Bergström, engaging the wingbacks of the opposition’s back five.

A typical feature of Mjällby’s build-up against a more passive high press or high block is their narrow four-man first line. The two outer centre backs spread roughly to the width of the penalty-area edges. The central centre back (usually on the left) and the goalkeeper (usually on the right) form the inner pair of this line. The extreme narrowness of this four-man row is notable. While many top European teams build with a slightly wider back three, Mjällby positions four players in a tight horizontal line.

The aim, beyond achieving numerical superiority, is likely to enable passing routes around the pressing block. Through the flat and narrow positions of the nominal fullbacks in the first line and the high positioning of Johansson and Stroud, the entire wing channel is opened. Typically, one of the central midfielders drops into that space to become available. The passing angle into the wide channel is optimal because the dropping player does not need to move all the way toward the touchline. Instead, he can remain closer to the centre, with shorter distances and better conditions to play back inside.

Due to the narrow back four in the build-up and the high positioning of the full-backs, the number tens can receive the ball around the block without having to drop all the way out to the touchline.

The heart of the build-up in this match lay in the central area. The basic structure was a trapezoid shape with the initially narrower positions of the sixes, Gustafson and Gustavsson, and the slightly wider starting points of the 10s, Bang-Kittilsen and Manneh. To continuously generate new passing options, Gustafson, Bang-Kittilsen and Manneh constantly searched for fresh open lanes and spaces to position themselves in. Initially, Gustafson often pushed deep into the large space between the lines, which prompted the two other 10s to adjust and occupy alternative passing lanes. This created constant rotation and caused problems for Degerfors.

From Degerfors’ perspective, they were outnumbered centrally against Mjällby’s four central players. When one of the 10s attacked a lane through the pressing block, another central player reacted by creating a passing option around the block. By dropping and offering an outlet outside the pressing trap, Degerfors faced a dilemma. If they closed the passing lane to the dropping midfielder, they opened a new channel through the centre. As a result, Mjällby repeatedly managed to open new passing routes and break the press through the rotating midfielders. The same logic applied in their build-up against Degerfors’ mid block, which will be examined again in that section, this time supported with an additional graphic.

AIK – Mjällby (2–1) on 11 May 2025

Mjällby operated in this match primarily from a 3-diamond-w2-d1 structure. The diamond in midfield was formed by captain Gustavsson as the six, Rojkjaer (a six in the 3-4-2-1) as the left eight, Gustafson (a ten in the 3-4-2-1) as the right eight, and Manneh as the ten. In contrast to the match against Degerfors, the fullbacks Stroud and Johansson were not supposed to remain permanently on the height of the last line. Instead, they dropped towards the ball on the outside lane especially when AIK managed to put pressure on the outer centre back in the build-up. As a general rule, Mjällby’s fullbacks act as the width providers in the build-up against a high-pressing opponent.

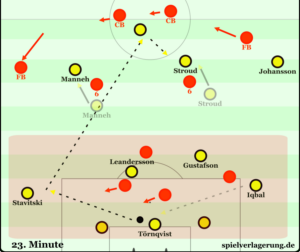

AIK used pure man marking in both the high press and on goal kicks. Unlike Mjällby’s other opponents, AIK did not maintain a plus-one in the last line. Instead, one of their centre backs directly engaged ten Manneh. In addition, AIK’s defenders repeatedly pushed forward aggressively from behind onto the Mjällby midfielders in a man-marking manner to prevent any free player from emerging. This had the major advantage of not having to press in numerical inferiority in the centre.

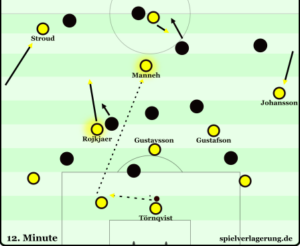

However, Mjällby managed particularly in the first 15 minutes to escape the man marking through a flat build-up. To achieve this, Mjällby used very flat eights and a ball-near fullback dropping towards the play. This created a kind of 5(GK)-3-1-2 structure, with one high fullback acting as the far-side striker and the other fullback staying flat as the ball-near option. The space between the lines was opened, with only ten Manneh positioned there, allowing him to exploit his strengths in larger spaces.

Mjällby’s 4-3-1-1-w2 with asymmetrical full-backs against AIK’s man-oriented marking: by creating an overload behind his direct opponent, Rojkjaer forces one of AIK’s centre-backs to loosen the man-marking on Manneh in order to provide cover, which makes Manneh available to receive the ball.

Mjällby succeeded in the early phases whenever they managed to “loosen” the man marking of the AIK centre back on Manneh. For example, eight Rojkjaer ran into the expanded space between the lines behind his direct opponent. Because this created a brief numerical inferiority for AIK, their marking centre back instinctively dropped off, allowing Manneh to be found as the free player between the lines. In general, Mjällby aimed in the build-up to open the centre in order to find the passing lane from a building defender into Manneh between the lines or into Bergström on the last line.

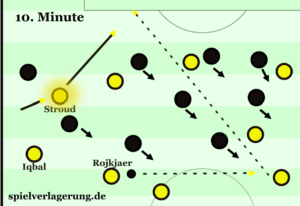

The fundamental objective of Mjällby’s build-up is to find the free player and then switch to the far side. If possible, this is done diagonally through the centre. Against man marking, however, Mjällby naturally encounters problems. Especially after Mjällby’s 1–0 goal in the 10th minute, AIK increased their risk-taking and applied tighter and earlier man marking. Because Mjällby’s build-up relies on freeing the central free player through coordinated movements, they struggle against pure man marking, in which no such free player appears. This theme runs throughout the entire analysis of their build-up against high pressing and becomes particularly relevant after taking the lead, since opponents then tend to abandon their cover and their plus-one advantage in the last line.

Of course, Mjällby also has mechanisms against pure man marking. Against AIK, a clear 5-3-1-2 structure appeared in goal-kick situations. Right back Johansson dropped very deep, while left back Stroud moved into the centre and high into the second-striker line. The idea behind this recurring goal-kick structure was to force the opponent either into a 3-versus-3 without cover or to abandon their man marking and instead pull an additional covering player backwards.

Mjällby’s 5-3-1-2 with asymmetrical wing-backs against AIK’s man-oriented marking at goal kicks: counter-movements in the front line and a counter-pressing net created by supporting runners stepping up.

Because AIK chose pure man marking without a covering player when full man marking the goal kick, Mjällby often went long to one of the three advanced players, frequently fullback Stroud, who dropped into the opened wide channel and laid the ball off to the players running through. The runners (the three midfielders and the ball-near fullback from the 5-3 structure) tried both to create lay-off options and to form a counterpressing net to win second balls. It is generally noticeable that Mjällby, due to their strong central occupation in the build-up against high pressing, wins a large number of second balls after turnovers. This is also a key part of Mjällby’s build-up play.

At the same time, Mjällby prepared the long balls on goal kicks through opposite movements of the three forward players. Before the ball was played, they made horizontal opposite runs to loosen the man marking and to gain more space and time on the lay-off.

It is also noticeable that the tighter the opponent moves into man marking, the more frequently striker Bergström is used as a target player. Whenever Mjällby came under pressure, the ball was often played into Bergström, who with his back to goal could hold the ball and lay it off to the midfielders running beyond him. Mjällby repeatedly managed through the movements of their midfielders to open the central passing lane or the direct ball into striker Bergström. Against AIK, Bergström was often found diagonally by Johansson, the flat fullback, from the touchline, or directly through a flat throw from goalkeeper Törnqvist. Bergström also served as an additional target player on goal kicks alongside fullback or striker Stroud.

Mjällby – AIK (2–0) on 20 July 2025

As the nominal holding midfielder Rojkjaer transferred to Danish top-flight club Nordsjaelland during the summer transfer window, he was replaced by number eight Thorell in the return match against AIK. Due to weather conditions, the Allsvenskan pauses during winter and is played throughout the summer, meaning departures can occur mid-season. On the left side of the back three, Pettersson started instead of Iqbal, maintaining the same role and positional profile. In attack, Johansson started in place of the usual first-choice striker Bergström.

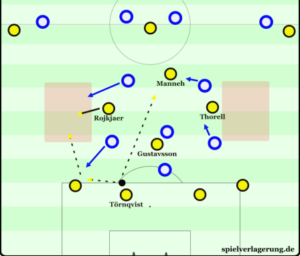

In contrast to the first leg against AIK, Mjällby used a slightly different central structure. As left-sided eight Thorell positioned himself higher than six Gustavsson, and right-sided ten Gustafson operated even higher than Thorell, this shape can be described neither as a diamond nor as a trapezoid. The most accurate description is a “Y-structure”. This highly interesting structure consists of Thorell and Gustavsson staggered vertically and slightly horizontally, supported by two tens.

Due to the staggered positioning of the two number sixes, a kind of diagonal “Y” shape emerges in central areas. From this structure, a variety of counter-movements with changes of vertical levels can be created, which are particularly difficult to defend against in a man-oriented marking scheme.

The Y-structure offers several advantages, particularly against man marking. Crucially, the Y is not fully symmetrical in its initial positioning. Because Thorell as an eight always started slightly offset from six Gustavsson, he formed a diagonal either with the left or the right ten. From this diagonal, it becomes significantly easier to generate varied horizontal opposite movements combined with changes of level. These movements are especially difficult to defend in a man-marking system, as they disrupt the opponent’s structure and greatly extend pressing distances. Defensive handovers also become much more difficult, since the diagonal Y allows for a wide range of possible opposite movements with level changes.

The diagonal Y also provides additional advantages against non-man-marking pressing. From this structure, the build-up players can quickly occupy a variety of passing lanes, and central access can be opened through easily created lateral overloads. The shape is also beneficial for lay-off play. Because multiple vertical levels are occupied simultaneously, simple movements can create several different lay-off options. The vertical staggering also improves counterpressing, as immediate mutual cover is available in transition moments.

As a result, a wide variety of movements could be observed from Mjällby within this Y-structure, making the central organisation appear almost random at times. In particular, eight Thorell could be found in nearly every area of the pitch. It was also helpful that the central players frequently rotated positions and roles among themselves. Since each player interpreted the respective role slightly differently, the build-up became even harder for AIK to read. This allowed Mjällby to progress the ball successfully on numerous occasions. As the first half progressed, AIK were also less frequently able to maintain numerical equality on the last line, which in turn created an extra player in midfield for Mjällby.

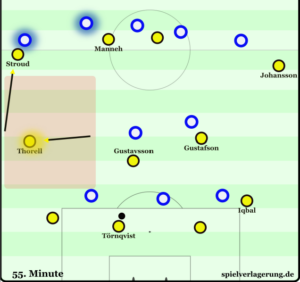

In contrast to the first leg, AIK initially defended goal kicks with a plus-one advantage on the last line. On goal kicks, Mjällby attempted to build in a similar way to the first leg, using a 5-3-1-2 or 5-3-3 structure, with left back Stroud positioned more centrally and higher in the forward line, and right back Johansson remaining flat and wide in the five-man build-up line. In this match, however, ten Manneh was much more involved in the opposite movements used to prepare long balls, which explains the shift towards a 5-3-3 instead of a 5-3-1-2. The three forwards moved unpredictably before the long ball, aiming to loosen man marking, remain difficult to access directly, and gain more time and space for lay-offs to the players arriving from deeper positions.

After approximately eight minutes, AIK adjusted their four-versus-three advantage on the last line. From that point on, one of their defenders was ready to step out onto one of Mjällby’s eights. Notably, Mjällby did not immediately choose the long ball from the goalkeeper in response. Instead, they first triggered the press through a short build-up and then played through it. There were several different variants of how the central players could behave in these situations. For example, one side could be overloaded by all three central midfielders, opening a diagonal passing lane to the far side towards striker or ten Manneh.

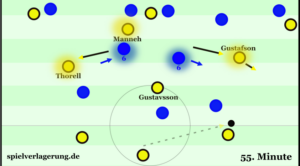

Around the 55th minute, a successfully executed goal kick from the asymmetrical 5-3-3 structure led to a free kick, which subsequently resulted in Mjällby’s 1–0 goal. First, the press was triggered by two passes between the goalkeeper and a centre back. From the opposite movements of the forwards, two attackers dropped towards the ball while one ran in behind. One of the forwards, in this case Manneh, was found directly with a flat diagonal pass into this lane, allowing him to turn and access the far side around fullback Johansson. As I cannot provide the video material on this page for legal reasons, I have linked the sequence as a video on X:

(2) Spielfeld Zauber auf X: „Mjällby vs. AIK https://t.co/UEGEtOIRgz“ / X

Norrköping – Mjällby (1–1) on 26 May 2025

In the match against Norrköping, Mjällby initially started with nominal holding midfielder Rojkjaer on the left and nominal number ten Thorell on the right in central areas, once again operating from a diamond midfield in which Rojkjaer and Thorell formed the two eights. Mjällby’s fullbacks initially started in a high position, similar to the approach against Degerfors, level with striker Bergström. However, they repeatedly vacated this high position in order to break down the opponent’s pressing, as will be explained below.

Norrköping pressed from a 4-2-3-1, shifting into a 4-2-4. This meant that against Mjällby’s 4-diamond-w2-d1 or 4-diamond-3 with high fullbacks, Norrköping’s two holding midfielders had to press in numerical inferiority against Mjällby’s two eights and number ten Manneh. As a result, Norrköping’s two sixes constantly shifted between these three players, taking responsibility for the ball-near central players. Similar to the behaviour of the sixes, Norrköping’s fullbacks also oscillated between the last line and Mjällby’s high fullbacks. On the far side, the fullback dropped into the last line to maintain numerical superiority, while on the ball-near side the high opposing fullback was picked up.

The 4-diamond-3 build-up against a 4-2-3-1 pressing structure: by having Mjällby’s number eights drop deeper, Norrköping’s number sixes are forced into very large shifting movements within the press.

Mjällby’s objective in the build-up was to create long pressing distances and constant dilemmas for the opponent. The behaviour of the two eights was crucial in this regard. With the fullbacks positioned high and the outer centre backs staying flat, a free wide zone once again emerged, opening the passing lane around Norrköping’s pressing block. Mjällby’s eights repeatedly dropped into this zone, forcing Norrköping’s sixes into very long lateral and recovery runs. One generally important tool for Mjällby, and a decisive one in this match against Norrköping’s high press, was switching play via the goalkeeper Törnqvist, who acted as an additional outfield player.

These switches, in combination with the dropping movements of the eights, created extremely long distances for Norrköping’s oscillating sixes and fullbacks. After switches of play, it therefore also occurred that Mjällby’s fullbacks left their high positions, dropped towards the ball, created an option around the block and forced the opposition fullbacks, who were still tucked inside, into similarly long runs.

The dropping movements of the eights also pulled Norrköping’s sixes out of the centre, opening central spaces and thereby the direct diagonal passing lane from the four-man build-up line into number ten Manneh or striker Bergström. Likewise, when holding midfielder Gustavsson dropped into the central centre-back position, his direct opponent was pulled out of the centre, which contributed to Norrköping shifting into a 4-2-4 press. Mjällby repeatedly sought these flat diagonal passes through the centre, not only against Norrköping, and could bypass up to six opponents with a single pass.

A key feature of Mjällby’s play is that after a diagonal penetrating pass, immediate lay-off options are created by the supporting runners. This allows quick wall-pass combinations to the far side. Alternatively, such diagonal penetrating passes are played as dummy passes. In most cases, number ten Manneh acts as the decoy and deep runner, while Bergström receives the ball and sets it for the supporting players.

Because the number eights drop deeper, the centre is opened up, which frees the diagonal vertical passing lane to Manneh and striker Bergström.

Against Norrköping, the central players consistently moved up in a triangular shape, emerging from the diamond, which not only secured lay-off options but also allowed them to immediately regain second balls after unsuccessful diagonal passes and switch play to the far side. Mjällby are repeatedly able to win such second balls due to their central numerical superiority.

Although Mjällby deservedly went into half-time with a 1–0 lead, they adjusted their build-up structure after the break, including on goal kicks. Such changes are likely made to reduce predictability, as opponents can adapt their pressing during the interval. Mjällby’s fullbacks now moved inside on the last line, while eight Thorell on the right and number ten Manneh on the left dropped deep into the newly opened wide lanes. This prevented Norrköping from compensating for their numerical inferiority through oscillations by the sixes or fullbacks.

The new build-up structure at Mjällby’s goal kicks in a 4-trapezoid-d3, with the number tens dropping deeper and the full-backs moving inside, initially creates chaos in the opposition pressing, as the number tens cannot be picked up.

As a result, Mjällby built up from a 4-trapezoid-d3, with the two number tens, Thorell and Manneh, positioned wide. This change caused significant assignment problems for Norrköping for approximately ten minutes, during which they occasionally defended in numerical inferiority on the last line. Mjällby were unable to capitalise on this brief advantage. Instead, Norrköping subsequently switched to pure man marking. As mentioned earlier, this causes problems for Mjällby in the build-up, particularly when opponents switch to pure man marking during the course of a match. In general, shifts to pure man marking often follow a deficit, as teams tend to abandon their covering structures and their plus-one advantage on the last line.

Such problems are not surprising but rather typical. A team in possession must build up in a fundamentally different way against pure man marking than against, for example, a hybrid pressing approach. Making this adjustment during the match is naturally very difficult. This also explains why Mjällby often struggle in the build-up after taking the lead and increasingly resort to long balls.

Malmö – Mjällby (1–3) on 9 August 2025

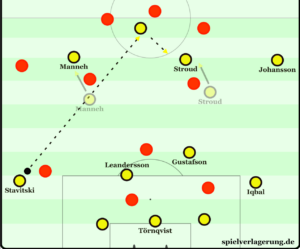

In the match against serial champions Malmö, Mjällby completely adjusted their build-up play. From a personnel perspective, little to nothing changed compared to the usual lineup. With Thorell as the left-sided six or eight, Gustafson as the right-sided eight or ten, alongside number ten Manneh and holding midfielder Gustavsson, the central areas were occupied in various configurations. As a reminder, the nominal starter Rojkjaer had left the club during the summer. In general, Mjällby still operated from a 1-3-diamond-w2-d1 structure in this match, but varied the spacing significantly, with specific target zones in the build-up, clearly defined patterns and adapted goal-kick solutions.

On goal kicks, Mjällby initially built up with a classic back four in front of goalkeeper Törnqvist, supported by two holding midfielders, two number tens and two forwards. To form the back four, the right-sided outer centre back of the back three, Iqbal, pushed wide and slightly higher to take up the right-back position. Although Iqbal is physically tall, he is technically capable and therefore well suited to this fullback role. On the opposite side, fullback Stroud formed the left-back position.

The two sixes, Gustavsson and Thorell, dropped very deep, almost to the edge of their own penalty area, positioning themselves level with the fullbacks in the back four. The two number tens, Gustafson and Manneh, positioned themselves wider and significantly higher to complete the central structure. In the forward line, fullback Johansson and striker Bergström initially operated just behind the tens. As a result, Mjällby built up from a 3(GK)-4-2-2 structure, a completely different spacing compared to the previous matches, with altered role distributions and partially new target zones.

Malmö’s 5-2-3 pressing has difficulties picking up Mjällby’s wide players. Mjällby therefore builds up unusually from a 1-4-2-2-2, and consequently from a 3-4-2-2 at goal kicks.

Malmö pressed from a 5-2-3, with the back five shifting in a classic manner. The ball-far wingback dropped into the last line alongside the centre backs, while the ball-near wingback pushed forward aggressively. Because Malmö’s two sixes focused on man marking Mjällby’s holding midfielders, Malmö were forced to cover the two forwards and the number tens through the back five. This proved problematic in the opening minutes. At the same time, the wide positioning of Iqbal and Stroud in the back four meant that Malmö’s three players in the first pressing line could not cover all options. They naturally prioritised ball-near pressure, leaving the far side completely unoccupied.

As a consequence, Malmö struggled throughout the match to deal with Mjällby’s wide occupation within their pressing structure, something Mjällby exploited in a variety of ways. In the opening minutes, Malmö were still experimenting with how best to press Mjällby’s 3-4-2-2 structure. In the very first sequence, number ten Manneh, who had not yet been picked up by one of Malmö’s centre backs, was found with a flat diagonal pass through the centre by one of Mjällby’s build-up defenders.

From open play, Mjällby’s central players also varied their spacing. Depending on the situation, they built either in a diamond or a trapezoid. What remained consistent was that Mjällby continued to build with a wide back four or, including the goalkeeper, a back five. Unlike on goal kicks, Johansson operated as a high fullback from open play, which led to an unusual double occupation of the right side by fullbacks Iqbal and Johansson. On the left side, number ten Manneh was able to attack the vacated wide channel.

The objective in the build-up remained to repeatedly exploit the wide zones that Malmö were unable to cover due to the execution of their press, primarily through switches of play. A key factor in creating the overload on Mjällby’s right side was that Malmö’s left-sided outer centre back did not follow Mjällby’s right-sided ten, Gustafson, all the way forward. Instead, he handed him over to the left midfielder, which tied that player into central coverage and prevented him from pressing fullback Iqbal. This created a two-versus-one overload on Mjällby’s right side, allowing Iqbal to carry the ball diagonally forward on several occasions with little pressure.

Because Malmö’s left-sided outer centre-back hands Gustafson over to Malmö’s left number six, Iqbal, who therefore acts as a full-back, becomes free on the flank.

In the second half, Mjällby also managed to create a structural wide overload on the left side. Initially, left-back Stroud pushed very high to directly bind Malmö’s wingback from the back five. At the same time, the entire three-man build-up line around goalkeeper Törnqvist shifted slightly to the left to compensate for Stroud’s absence from the first line. As a result, fullback Iqbal positioned himself slightly deeper but still remained free when stepping higher into wide areas.

Because Gustafson, who pushed high in the build-up as described earlier, was not followed by Malmö’s outer centre backs but instead picked up either by the ball-near left six or the ball-far left midfielder, eight Thorell was able to move into the now-vacated wide zone on the left and became freely available. Once again, Malmö were unable to cover Mjällby’s wide occupation within their pressing structure, resulting in a complete lack of pressing access.

Thorell, who moves out wide, also cannot be picked up in Malmö’s pressing. The number sixes are unable to shuttle across due to the long distances, and the last line of Malmö’s defence continues to face a plus-one overload.

As a result, Mjällby played direct high switches to free players in the wide zones far more frequently than usual. Mjällby deliberately provoked Malmö’s inability to cover wide players from their 5-2-3 pressing shape, ensuring that Malmö failed to establish effective high pressing control for long stretches of the match. However, after conceding the 2–0 goal, Malmö switched to pure man marking, at least on goal kicks. It remains questionable why pure man marking with handovers between the outer centre backs and wingbacks on the flanks was not implemented earlier. In any case, following this adjustment and particularly after taking the lead, Mjällby once again encountered significantly greater difficulties in their build-up play toward the end of the match.

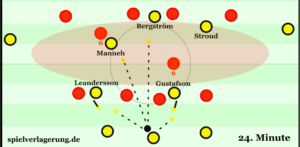

Mjällby – Elfsborg (2–0) on 4 October 2025

Against Elfsborg, Mjällby once again started from their classic 1-3-2-4-1 structure, with two holding midfielders and two number tens in central areas. In place of captain Gustavsson, Leandersson moved into the holding midfielder role. Gustafson operated as the right-sided six, while the nominal left back Stroud played in the right half-space as a number ten, with Manneh occupying the left-sided number ten position. Stavitski started as the left fullback.

Against Elfsborg’s 4-2-3-1 press, Mjällby again relied on an asymmetrical back-four build-up, which became a back five with the goalkeeper involved. The fullback positions in the back four were occupied by the outer centre back Iqbal on the right and the left back Stavitski on the left. Accordingly, right back Johansson pushed high onto the right wing, while Stavitski was able to vary his height and was more often positioned deeper. This created long pressing distances for his direct opponent, Elfsborg’s right back. Because these distances were too long to cover, Stavitski was frequently pressed by one of the four players in Elfsborg’s first pressing line. As a consequence, Elfsborg’s right back became redundant in the press due to the vacated right flank.

As a result, Mjällby were able to create periods with a seven-versus-four overload in the build-up zone. The three additional players were formed by the fullback who did not push high, the plus-one created by the two centre backs against striker Bergström on the last line, and the goalkeeper acting as an outfield player. With this level of superiority, Mjällby had little difficulty escaping pressure, identifying the free player and progressing the ball cleanly from the back. In particular, flat switches via the goalkeeper to the opposite side, as well as direct high switches from the left to the ball-far and free Iqbal, proved to be effective tools for exploiting the overload.

The 7v4 overload in Mjällby’s build-up zone ensures control in possession. Through switches of play, the free player can be found, who then initiates the attack with the typical diagonal pass into central areas to Manneh and striker Bergström.

When Mjällby managed to bypass the first pressing line, they usually looked to access the centre diagonally. With striker Bergström acting as a target player and the two number tens providing lay-off options or acting as dummies, Mjällby were able to find the ball-far side through central combinations and continue attacking depth from there.

General principles of Mjällby’s build-up play

It is clear that through targeted analysis of the opponent’s pressing, Mjällby are repeatedly able to gain advantages in their own build-up play. Rarely has an analysis been as challenging in terms of understanding why a player moves where he does. Especially against high pressing, Mjällby adapt their build-up specifically to the weaknesses of the opponent.

Nevertheless, there are also general principles and recurring patterns that can be identified in Mjällby’s build-up against high pressing. One notable feature of Mjällby’s play is the near absence of long-line passes. From wide areas, and whenever possible, the ball is instead played diagonally into the centre almost immediately. Mjällby only briefly stretch the opponent horizontally before opening up central space. The team therefore does not remain for long in the wide channel constrained by the touchline, but rather uses it as a tool to subsequently attack through the centre. This approach often also functions in build-up play through so-called escadinhas. In these situations, striker Bergström usually acts as the target player, while one of the number tens makes the overlapping run.

Typical of Mjällby’s build-up play is a diagonal escadinha into central areas, followed by a switch to the far side.

Mjällby consistently aim to create a free player and then find this free player in a space that has been drawn open within the opponent’s structure. Accordingly, in their build-up against high pressing, Mjällby deliberately stretch the pitch and operate with larger distances between players. Even though they are not afraid to play through the centre under pressure in these phases, the overarching objective remains to identify the free player, most often one of the four centrally positioned and differently staggered midfielders. Once the free player has been found, Mjällby typically look to access the ball-far side in order to achieve further progression from there.

Mjällby’s Higher Build-Up Against a Mid-Block and Deeper Pressing

In build-up play against deeper pressing structures, whether a defensive press or a midfield press, Mjällby also vary their central spacing. Whether they operate with a diamond, a trapezoid, one holding midfielder and three number tens, or three holding midfielders and one number ten can differ not only between matches but even within the same game. However, the build-up against deeper pressing often mirrors the approach used against the opponent’s high press. For example, if Mjällby build from a diamond against higher pressing, they will usually also build from a diamond against deeper pressing.

That said, the central arrangements become less rigid in the higher build-up. The central players orient themselves less toward fixed geometric shapes or predefined zones and more toward potential passing lanes and windows. As a result, it can appear as if Mjällby’s central players are given greater freedom in build-up play against deeper pressing. Mjällby’s play in central areas is particularly fluid, as players constantly search for new passing windows and react dynamically to them.

The 3-1-3-1-w2 as the base structure

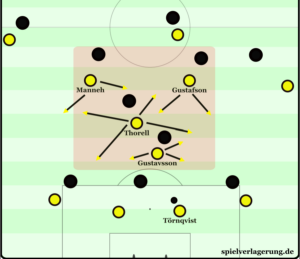

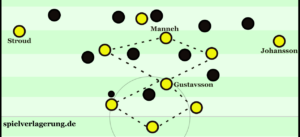

In the match against Degerfors, these freedoms could be observed particularly clearly. In principle, Mjällby built up with one holding midfielder and three number tens. As a result, a narrowly staggered 3-1-3-1 structure emerged in central areas, supplemented by fullbacks who also frequently left the wide zones. The most accurate description is probably 3-1-3-1-w2, where the wide two (the fullbacks) does not imply that the fullbacks are bound to the touchline, but rather that they initially provide width.

Mjällby’s approach against higher pressing is also driven by the fact that the fullbacks repeatedly overload the centre on one side or attack depth in the half-space behind the last line. Because Mjällby do not always replace these wide positions, it would, strictly speaking, be inaccurate to refer to this as a permanent wide two. However, 3-1-3-1-w2 remains the most comprehensible description of their build-up structure.

Since Mjällby also started against Degerfors with three nominal number tens (Gustafson, Bang-Kittilsen and Manneh), this match offered a particularly clear illustration of how the central players are meant to interact. The starting point lies in the potential passing lanes to be occupied. If one of the number tens occupies a lane through the block, another ten looks to position himself in a passing window around the block. This either stretches the opponent, opening an additional lane through the block that can then be occupied, or allows the player to be found around the block in the half-space. In this way, the number tens rotate continuously, at times all three occupying the ball-near side, creating numerical superiority while remaining difficult to track.

The rotations of the three number tens: if Manneh becomes available to receive through the block, Bang-Kittilsen looks for the passing lane around the block. Gustafson also becomes available diagonally through a gap between the lines.

Exploiting central overloads: positioning in the space between the lines

From the 3-1-3-1-w2, as well as in other matches from structures such as the 3-2-2-3 or the 3-diamond-3, Mjällby are repeatedly able to overload the space between the opponent’s midfield and defensive lines. Particularly noticeable, including against Degerfors, is the positioning of the players involved in these overloads. While striker Bergström is positioned directly on or immediately in front of the last line, the number tens overload the space between the lines by positioning themselves just behind the opponent’s midfield line, rather than in the middle of the space itself. This has the advantage of avoiding immediate access from the defensive line while simultaneously remaining in the blind side of the midfield line.

If the defence steps out to engage the number tens positioned in this way, Mjällby look either to attack the space behind the last line through the fullbacks or to release one of the number tens into depth. In general, Mjällby frequently seek rapid progression, including direct balls in behind the defensive line. This forces the opponent to either refrain from applying pressure on the number tens or to neglect depth protection. As a result, the threat of balls played in behind ensures that the space between the lines remains large enough to be accessed through flat combinations.

The role of the fullbacks and the three-man build-up line

It is also noticeable that the fullbacks generally look to attack depth as soon as Mjällby circulate the ball backwards or the opponent’s defensive line steps up. The typical running patterns of Mjällby’s fullbacks initially lead from wide areas toward the centre before continuing with diagonal runs in behind the last line. As the last line steps up, these movements create opposite runs, making it difficult for the opponent to defend depth in these moments. In the first leg against AIK, one such movement by fullback Stroud led directly to the opening goal.

After a lay-off or square pass, AIK are provoked into stepping out. Stroud then attacks the depth diagonally from the outside and scores the 1–0.

As already indicated, Mjällby do not always maintain wide occupation in the higher build-up. Frequently, one of the fullbacks, usually the ball-far one, moves inside to the height of the last line and thereby further overloads the space between the opponent’s lines. If the ball-near fullback moves inside and provides an additional passing option through the opponent’s block, one of the central players usually creates a passing option around the block. This option does not necessarily have to be on the touchline.

Due to the very narrow positioning of the three-man build-up line, passing options around the block also emerge at the boundary between the half-space and the wide channel. As a result, Mjällby do not have to move into the extreme wide lane close to the touchline. In addition, the three-man build-up line is not positioned flat. Instead, the two outer centre backs step slightly higher, while the central centre back remains deeper as an anchor. This places the outer centre backs almost level with the holding midfielder or midfielders, creating additional vertical layers that the opponent must press. The higher positioning of the outer centre backs is also explained by their strong involvement in advancing play into the final third.

The 3-diamond-3, also described as a 1-2-1-2-1-1-w2, contains multiple vertical layers, which creates a wide variety of central passing options.

Central players reacting to pressing and blocking opponents

Mjällby’s centre backs receive significantly more support from the central players, especially against opponents who press or apply direct pressure on the ball carrier. When the opponent looks to press Mjällby’s back three, the focus of two or three central players shifts to positions immediately behind the opponent’s first pressing line. If Mjällby build up from a diamond, this results in two or three holding midfielders overloading the build-up zone and providing direct passing options. If the opponent instead focuses on blocking or defends in a mid-block, the diamond shifts into the previously described 3-1-3-1 structure with three number tens.

These supportive movements of the central players, starting from a diamond, were particularly evident against Malmö’s 5-4-1 blocking and 5-2-3 midfield pressing. Thorell in particular repeatedly overloaded the build-up zone, ensuring that two holding midfielders supported the defensive line against Malmö’s pressing. When Malmö dropped into a blocking phase, Thorell instead contributed to overloading the space between the lines between Malmö’s back five and midfield four. This resulted in the described 3-1-3-1 build-up or, with the outer centre backs stepping slightly higher, a 1-3-3-1 structure.

Here is the linked video sequence of Thorell supporting first the build-up zone, then the space between the lines:

Against Elfsborg, Mjällby primarily built up from a 3-2-4-1 / 3-2-2-3 / 3-trapezoid-3 structure. As Elfsborg repeatedly transitioned from a 4-2-3-1 midfield block into active pressing, supportive movements from the holding midfielders were required. Gustafson and Leandersson, the two sixes in this match, repeatedly dropped into the build-up zone, at times positioning themselves in front of the first pressing line. This made Mjällby more resistant to pressure and simultaneously stretched the centre. As a consequence, Mjällby were able to play through the resulting 4-2-4 press via the centre, finding striker Bergström or one of the number tens, often through lay-offs.

Mjällby build up in a 3-2-4-1 against Elfsborg’s 4-2-4 mid-block. By having the number sixes drop towards the ball, a local overload is created and the space between the lines is stretched.

Against Elfsborg, Mjällby did not stretch the centre only through deeper positioning of the holding midfielders. Wider positioning of both the sixes and the number tens was also used to open direct passing lanes to striker Bergström through the now-expanded central areas. Mjällby are repeatedly able to play through the centre precisely because of these shifts from narrower to wider positions, which stretch the opponent again. Once the opponent is stretched, the diagonal pass through the centre typically becomes available. If one of the forwards or number tens is found, play can again be progressed through effective lay-off combinations, supported by the strong central occupation.

When the opponent plays with only two holding midfielders, a common solution is to have the eights or central midfielders drop wider, while the fullbacks move inside on the last line. This places the two sixes in a dilemma between protecting the centre and applying pressure. This approach also worked very effectively against Malmö. The two eights in the diamond, Gustafson and Thorell, repeatedly dropped into wide areas, creating constant dilemmas for Malmö’s defensive structure.

Against Malmö’s defensive pressing in a 5-2-3, Mjällby’s number eights drop out wide to become available for passes. This makes the shuttling movements of Malmö’s two number sixes too extensive.

Mjällby’s potential and development

Despite their attractive central play, Mjällby still have significant potential for development in this very area. Especially in earlier matches of the season, the team struggled to consistently exploit appropriate central structures. This was particularly evident in the first leg against AIK. At that time, Mjällby’s play was strongly oriented toward immediate progression. Against AIK, this led to the centre backs frequently playing high balls over the block, even though suitable central structures were available to play through the 5-4-1 block with its very narrow back four. The result was a number of turnovers, which reduced the team’s otherwise existing dominance.

In later matches of the season, such as against Malmö or Elfsborg, Mjällby were far more successful in establishing longer phases of possession, playing less hastily into depth and thus dominating the opponent through controlled ball circulation. Especially against deep-defending opponents, there is considerable potential in suffocating the opposition through tighter spacing and longer possession phases. This is precisely what the next section will focus on.

Mjällby’s Play Into the Final Third and Build-Up Against a Low Block

One of the reasons why Mjällby stand apart from the classic style of European football lies in how they attack a low block. The way Mjällby play against deep-defending opponents is very likely to become more common in the major European leagues over the coming years. The positional play used by most teams is based on stretching specific spaces in order to exploit them afterwards. This works well by repeatedly forcing the opponent to shift until a free player eventually emerges. Against deep blocks over a full 90 minutes, however, this type of possession play often works only to a limited extent, or not at all.

Deep-defending opponents are positioned so compactly around their own goal that decisive spaces are difficult to open. The team in possession can circulate the ball around the block but struggles to find access to a free player through it. Due to the compactness of the defending team, alternative solutions are required. This is also one of the reasons why many teams have returned to using classic centre forwards who are strong in the air and in finishing, and who can be found in the box through crosses even without playing through the tight block.

Side/ wide overloads

Mjällby, by contrast, usually do not rely on a classic positional or spatial structure when playing into the final third or against a low block. Instead, they very often look to combine through side (/wide) overloads. Especially in the earlier matches of the season, such overloads in the wide zone were clearly visible. These are created through the ball-near outer centre back, the ball-near fullback, the three more advanced central players and the striker. Frequently, the side overload consists of five to six of these players.

The rest defence is usually formed by the central centre back, the holding midfielder, most often captain Gustavsson, and the ball-far outer centre back. It is important that Mjällby maintain a plus-one advantage in rest defence. If the opponent has only one counter-attacking player, the ball-far outer centre back also steps forward to join in. It is noticeable that on switches of play both outer centre backs regularly push forward, become involved offensively and can create additional danger, including inside the opponent’s penalty area. Box occupation is typically provided by the ball-far fullback and striker Bergström.

Mjällby’s classic pitch occupation against a low block: five to six players overload the ball side, while the far-side outer centre-back, the central centre-back and the number six form the rest defence, with the striker and the far-side full-back occupying the box.

Within the side (/wide) overload, positional roles play only a minor part. Instead, the focus is on combining toward the byline. The dynamism of the outer centre back is particularly helpful here. He is almost always involved in play during side overloads. The advantage lies in the momentum he generates by running forward from deeper positions. This presents an additional challenge for the defence, as another player arrives from behind with speed and must be picked up.

An anchor player is virtually always present and can be found through a backward pass at any time. This allows Mjällby to exit the overload and, by playing back into it, create a new dynamic and stretch the opponent again. The anchor player’s primary role is not to switch play to the far side. He is part of the overload and helps to resolve the tight pressure situation. A player occupying the width on the touchline is also always present. This stretches the opponent within a very small space. Crucially, the anchor role and the wide role rotate. The width is only initially provided by the fullback, while the anchor role is initially taken up by the outer centre back.

Also noteworthy is the positioning of the more central players. They look for positions in front of the last line, forcing it to decide whether to step up and apply pressure or to protect depth. If the last line steps forward, depth is attacked with opposite movements, allowing Mjällby to reach the byline more easily.

Within the overload itself, relational principles come to the fore: pass and move patterns (toco y me voy), wall passes/ one-two combinations (tabela), opposite movements and escadinhas in combination with letting the ball run (corta luz). I have linked two example videos on X that illustrate Mjällbys play within side (/wide) overloads.

When the ball is played back to the anchor player or moved further away from the overload, this often provokes the opponent to step out. This is followed by a diagonal run in behind from the outside and a high ball over the last line. Because positional assignments have been loosened by the preceding overload, these runs can be made by different players, but always by the player who had been occupying the wide position on the outside. An example video of this pattern is also linked.

A major advantage of playing through overloads lies in the tight distances between players. After losing the ball, the opponent must first spread out in order to secure possession. At the same time, Mjällby immediately have a large number of players close to the ball who can apply counterpressing. Over the course of the season, a clear development could be observed in this area. Increasingly, Mjällby were able to suffocate opponents through successful counterpressing actions. The high points came in the matches against Malmö and Elfsborg, where Mjällby were able to regain possession immediately through effective backward pressing after turnovers.

Nevertheless, there is still considerable potential for development here. Mjällby’s play is strongly oriented toward progression. As a result, after taking the lead, they often struggle to control the opponent through possession. Because they repeatedly look to progress toward goal very quickly, this also leads to more turnovers. Especially after going ahead, a useful means of establishing control could be to overload their own build-up zone, creating longer possession phases and forcing the opponent to step up with more players.

Diagonal play: diagonal overloads and inside diagonals

In order to be less predictable when attacking the final third, Mjällby also rely on central play using similar principles and structures to those described earlier against a mid-block. Usually from a 3-1-3-1-2 structure, they combine through the centre. What is particularly interesting is that Mjällby increasingly use diagonal overloads from the wide zone into the inside, diagonally toward the penalty area, or combine diagonally into the box from a side overload.

In this case, the overload no longer runs along the touchline but instead follows an imaginary diagonal axis from outside to inside toward the penalty area. The same relational principles are applied as in side overloads, though with a stronger emphasis on diagonal escadinhas and corta luz. One key advantage is that the target zone into which Mjällby combine can be used immediately for a shot. When Mjällby combine from a side overload toward the byline, a cross into the box is usually still required.

Even from side overloads, Mjällby increasingly look for diagonal routes from the touchline into the penalty area through so-called inside diagonals. These create diagonal staggerings of three or more players, which can most easily be played through diagonally using letting the ball run and lay-off combinations. The fact that Mjällby also produce such diagonal breakouts from side overloads naturally makes them less predictable for the opponent. Three example videos of diagonal play within overloads are linked here.

(1) M.H. auf X: „(8/8) Mjällby consistently create and look for diagonal options.“ / X

Diagonal play is not only a key tool against low blocks. Attentive readers may already have noticed that Mjällby also rely heavily on diagonality against high pressing and deeper pressing, either from wide areas into the centre or from in front of the block through the centre and on to the ball-far side. Why is that? Why does diagonality repeatedly appear as a stylistic element in Mjällby’s play?

Here, only the core ideas behind diagonality in possession play should be outlined. Diagonality combines the progression of verticality with the security of horizontality. This allows progression with greater ball security. In addition, it poses greater challenges for defenders in terms of visual perception. A staggered defence must orient itself while shifting both horizontally and vertically.

Defending teams typically perceive the pitch vertically. Classic formations are structured along an imaginary vertical axis, since play is logically thought of from goal to goal. The attacking team usually also looks to combine vertically toward the opponent’s goal. If, however, the diagonal is used as the imaginary axis in possession play, new passing angles, lanes and dribbling paths open up, because the opponent primarily closes direct vertical passing lanes toward their own goal. This also implies that if an opponent defends primarily along diagonal lines, a vertical or horizontal possession approach can exploit new passing lanes and gaps.

For the attacking team, diagonality means that multiple vertical layers can be bypassed at once, while the body orientation of the receiving player is optimal for the next action, as the ball can be taken forward immediately with the open foot. Visually, the attacker can simultaneously see the ball, a large proportion of teammates and the opponent’s goal. This, in turn, allows for more effective combination play even in tight spaces.

For those interested in the topic, which I was only able to touch on briefly here, I have linked a selection of articles on diagonality below.

https://spielverlagerung.com/2025/06/12/tactical-theory-diagonality/

https://spielverlagerung.com/2025/06/12/chat-gpt-diagonality-footballs-hidden-dimension-of-play/

https://medium.com/@stirlingj1982/the-diagonalist-manifesto-610bf3fbca15

https://jogofuncional1.blogspot.com/2025/12/the-art-of-diagonals.html?m=1

Conclusion

Mjällby AIF show several distinctive characteristics in possession. In build-up play against high pressing, it is rare to observe exactly the same plan. Not only can the spacing vary significantly, but the opponent’s pressing is analysed in advance to identify specific weaknesses and define targeted zones to be exploited. The centre is the heart of Mjällby’s build-up, enabling them to play through the opponent’s press with great effectiveness.

Against a mid-block, the central players take on a key role. Mjällby aim to combine through the centre whenever possible. In doing so, the central players constantly attack new passing lanes, open spaces and then reoccupy them. This makes them difficult for the opponent to pin down and allows them to evade defensive access. With four flexible central players who can be arranged in a wide variety of structures, along with striker Bergström and, situationally, a fullback, Mjällby possess a unique possession-based approach simply through the number of players they deploy in central areas.

Their approach against a low block is particularly striking. Here, Mjällby rely on combinations within pressure-based overloads. The tight spacing has the advantage of placing a large number of players close to the ball immediately after turnovers, making counterpressing far more effective and allowing the opponent to be suffocated near their own penalty area. A more recent development is Mjällby’s increasing tendency to combine diagonally from wide areas into the penalty area. These diagonal combinations are significantly harder to defend and add a greater level of unpredictability to Mjällby’s play in the final third.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Paul January 16, 2026 um 3:12 pm

Super interesting article, thank you! After following Allsvenskan closely this season I also identified some of the mentioned measures and patterns. Will be very interesting to follow Mjällby next season, also at an international stage.

Another observation I had, was that many of the elements reminded me of Bayer Leverkusen under Xabi Alonso, who were also dominating in nearly every game 23/24.