The Issue of Passivity – MX

A solid start was masked by an overly passive 5-4-1 and ultimately ended in a 5-1 defeat for Dino Toppmöller and Eintracht Frankfurt.

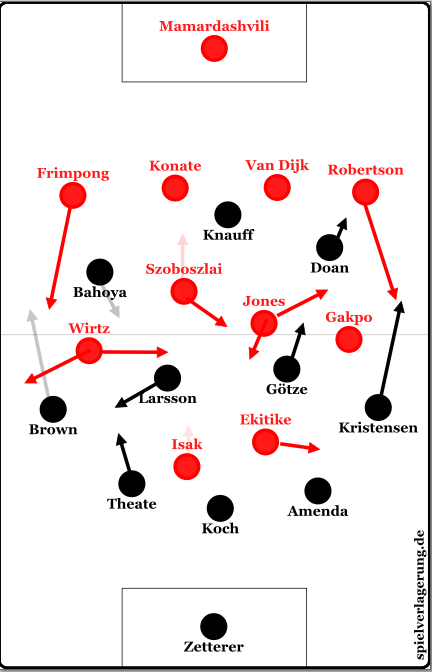

After three winless games, Eintracht Frankfurt faced Liverpool on Wednesday evening. Dino Toppmöller lined up in a 3-4-3 formation. Zetterer started in goal after extended discussions in the media. Amenda and Theate took up the half-back positions, while Koch operated as the central center-back. On the flanks, Kristensen and Brown were deployed. In midfield, Götze and Larsson formed the double-eight, with Doan and Bahoya on the wings and Knauff starting as the central striker.

The visitors from Liverpool arrived in Frankfurt with a similar situation: four consecutive defeats, including losses to underdogs like Crystal Palace and Istanbul. Arne Slot lined up in a 4-4-2 formation. Mamardashvili started in goal, with Konaté and van Dijk forming the central defense. On the flanks, Frimpong and Robertson defended, while Jones and Szoboszlai operated in central midfield as number eights. Gakpo and Wirtz occupied the wings, and up front, Isak and Ekitike formed the striking duo.

After the game, Markus Krösche said: “In the end, it’s about showing a completely different level of aggressiveness in the duels.” A topic that has been omnipresent around Frankfurt for weeks—and came into the spotlight again against Liverpool. But why did Frankfurt struggle so much to even engage in the duels?

This is a translated analysis. You can find the original here: https://spielverlagerung.de/2025/10/24/die-sache-mit-der-passivitaet-mx/

Liverpool with Incompact Number Eights

From the home side’s perspective, the game initially unfolded differently than the overall narrative suggested: it started off stable. In the first ten minutes, Dino Toppmöller’s side largely operated from a 3-4-3 structure in their higher build-up, with particular focus on the half-backs Theate and Amenda. Liverpool’s two forwards in the 4-4-2 mid-block struggled to gain access to the half-backs positioned in the half-spaces due to their narrow starting positions.

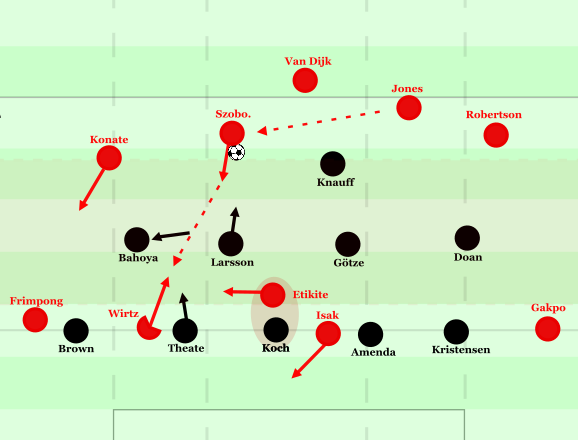

This repeatedly created horizontal pressing angles—i.e., side approaches—which carried a high risk of being dribbled past. Theate, in particular, was able to exploit this thanks to his very vertical first touch. Consequently, Liverpool’s number eights, especially Szoboszlai on Theate’s side, were often forced to move from the center into the half-space to press the advancing half-back. This opened central spaces next to them, into which Frankfurt’s number eights could advance and increasingly become available as passing options.

Hugo Larsson, in particular, was able to receive the ball from Theate multiple times, as the right number eight—Götze, or sometimes Doan and Knauff when positioned deeper—tied up Jones in Liverpool’s right half-space. This created, in the opening minutes, large pockets of space between Liverpool’s central number eights, allowing Larsson to push forward relatively freely.

Frankfurt Finds Larsson in the Center

This initially meant that Liverpool struggled to immediately disrupt Frankfurt’s build-up after the half-backs carried the ball forward. Often, the visitors responded by having Jones instinctively step out onto Larsson. However, due to the long pressing distance from the half-space into the center, he usually arrived late in the duel, allowing Larsson to hold onto the ball with his composure and often stabilize play via a relieving pass back to Theate. Jones stepping out also forced Gakpo, the far-side winger, to move into the half-space, reducing his ability to provide width for potential switches. Frankfurt, however, made too little direct use of these far-side spaces in the opening phase.

Larsson’s Focus on Breaking Free

Despite dropping deeper, Larsson’s focus was also on another problematic area in Liverpool’s pressing: the space between the first and second lines. The narrow positioning of the two forwards is meant to isolate passing lanes from Frankfurt’s first build-up line into the defensive midfielder. In practice, though, their adjustment to players dropping behind them—beyond their tight starting positions—was limited.

Larsson frequently found pockets in the blind spot between the two forwards and became available through central center-back Koch in the defensive midfield zone. Szoboszlai and Jones were often tied up in the half-spaces by the inward-running Bahoya or Kristensen, and the gaps between Liverpool’s first and second pressing lines were relatively wide, preventing them from intuitively stepping out onto Larsson.

Against the forwards’ rearward pressing, the Swede was able to turn effectively and drive into the center with the ball. In some cases, this movement primarily served to draw Liverpool’s double-striker formation together, thereby giving the half-backs more space for diagonal dribbles—here, Larsson often simply laid the ball off. At other times, he actively sought progression and diagonal switches to advancing players in wide areas, most often targeting Brown on the left flank, which proved fairly effective in the opening phase.

However, Wirtz’s active rearward pressing limited space for Bahoya in the deep left half-space, meaning left-back Frimpong didn’t need to step out. As a result, Brown was frequently isolated on the wing, repeatedly facing 1v1 situations, which he struggled to handle consistently.

Liverpool Reveals Spaces Both Wide and Centrally

Speaking of Bahoya: He frequently looked to make diagonal runs into the space behind Szoboszlai to get into the center and be vertically available for Larsson. However, Larsson struggled noticeably in these situations to find Bahoya in the right spaces. On one hand, this was because during his diagonal dribbles he focused heavily on the flank, sometimes neglecting scanning toward the center. On the other hand, this orientation also exacerbated Brown’s isolation on the left wing: with Bahoya positioned centrally, there were often few nearby support options, while Theate rarely pushed up consistently in these moments. As a result, Brown was frequently isolated in 1v1 situations without passing options.

Too Fragmented or Well-Focused?

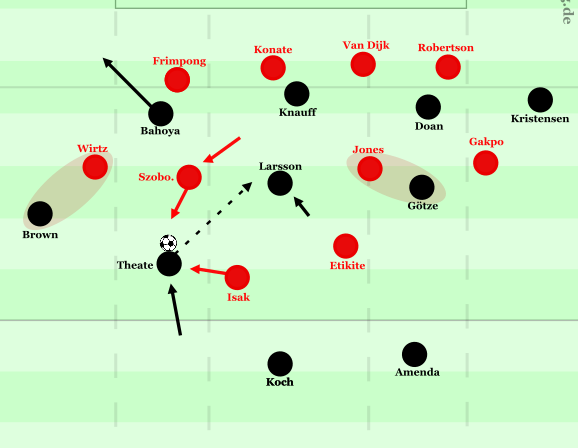

As Brown became increasingly involved in Frankfurt’s play, a new dynamic emerged: Wirtz pressed closer and more directly onto Brown, which opened up the vertical passing lane from Theate in the half-space to Bahoya, who repeatedly offered dropping movements.

At this point, one could discuss whether Liverpool’s pressing appeared too fragmented: on the one hand, the number eights were oriented too man-focused (see above), creating central spaces that were potentially exploitable. On the other hand, Wirtz’s wider positioning and Szoboszlai’s lack of compensatory movement meant these spaces were actively playable for Frankfurt. Or not?

Bahoya in Pressing Situations

On the other hand, it must be noted: what appears fragmented can also be well-prepared or intentional. While Bahoya was technically available as a passing option, Liverpool reacted very effectively in these situations. Right-back Frimpong tracked his dropping movements directly and consistently, while Wirtz and Szoboszlai stepped up, creating situations in the half-space where Bahoya faced 1v2 or even 1v3 disadvantages, simultaneously closing potential lateral passing options. Considering that Bahoya is primarily a player who looks to provide vertical depth rather than withstand direct pressure, this approach made sense: Brown was pressed more directly, Theate was forced into the half-space, and Bahoya came under immediate pressure, often leaving him with only the option of a backward pass.

Wirtz’s more direct stepping up also addressed an issue from the opening minutes. Frankfurt’s narrow starting positions had allowed Brown to remain available laterally to Theate, creating a very horizontal pressing angle. This enabled Brown to open up vertically and play deeper to Bahoya or carry the ball himself—something that ideally should have been prevented.

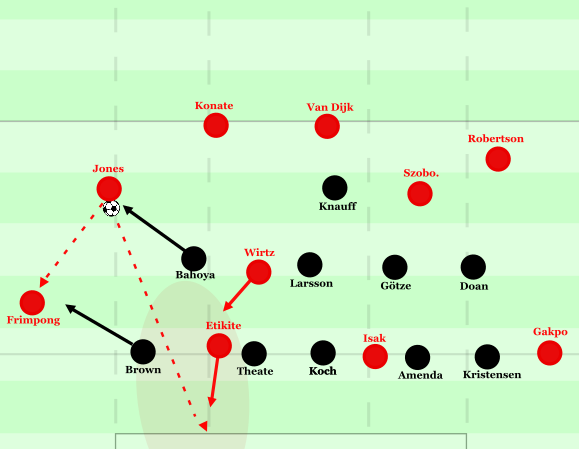

Frankfurt in a 5-4-1-Low-Block

After Frankfurt’s relatively stable start—facilitated by higher initial possession that gradually decreased due to enforced verticality—Liverpool increasingly found their rhythm. This was mainly because Frankfurt allowed it. The Eagles set up in a 5-4-1 deep block, prioritizing blocking rather than actively pressing. This was particularly evident with striker Knauff: he lightly tracked Liverpool’s half-space dribbles but rarely contested the duels actively. Consequently, there was no isolation on lateral passes from the first pressing line, allowing Liverpool to shift play between the center-backs and repeatedly dribble forward. Frankfurt’s midfield was forced into constant lateral shifts, which repeatedly opened spaces within the 5-4-1 block.

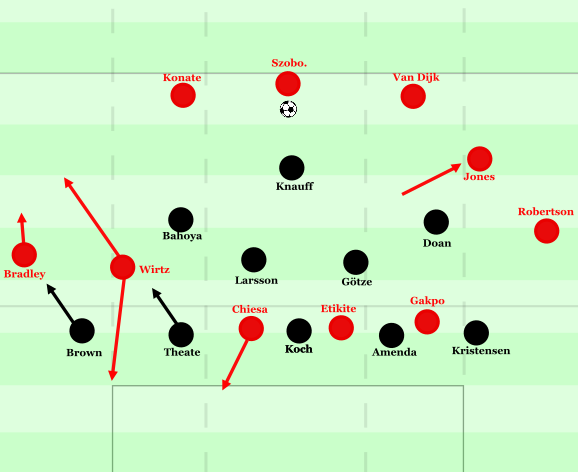

Liverpool thus created excellent conditions to exploit gaps inside Frankfurt’s 5-4-1 structure. Both number eights, Jones and Szoboszlai, occasionally broke forward ahead of Frankfurt’s second pressing line, acting as part of the first build-up line between center-backs and half-backs (or “wing backs”), creating temporary 5-0-5/3-2-5 spacing. The intent was twofold: first, technically strong players like Szoboszlai and Jones could dribble and exploit small diagonal spaces; second, the expansive build-up created direct backward passing options via central center-back van Dijk, enabling quicker lateral switches and further straining Frankfurt’s shifting.

The main aim, however, was to position as many players as possible around the block—both in front and behind—to force Frankfurt’s number eights to step out reactively onto Liverpool’s dribblers in the half-space, while simultaneously opening “blind-spot” spaces in front of the defensive line. Structurally, this was facilitated on the right by Konaté, who could push Szoboszlai wider from the half-right position. This, in turn, pulled Frankfurt’s left winger Bahoya slightly out of compactness (likely to prevent a 2v1 in width behind him), while Larsson was forced into more active blocking—slightly stepping up without actively contesting duels, creating minimal defensive shadow. As a result of these positional adjustments, spaces often emerged between Bahoya and Larsson, which Florian Wirtz sought diagonally.

Liverpool Seeks Ways Around the Block

This created some interesting patterns in the lay-off play. Ekitiké occasionally moved into the number 10 zone, positioning himself horizontally to the right following Wirtz’s diagonal runs, allowing Wirtz to lay the ball off to him. Since Wirtz immediately stepped back into the “play & move” rhythm, these pressure situations occasionally opened opportunities for direct forward progression into deeper areas—even if they were not fully exploited in the opening phase.

It also became apparent that a defensive focus on blocking inherently involves some degree of reactivity. Drops from the last line were not actively tracked but responded to reactively. The priority was securing depth first and defending only upon receiving passes. This approach gave Wirtz and Ekitiké additional freedom in the half-space—players of their quality can exploit such pockets effectively. This was particularly noticeable in the first-touch lay-off patterns.

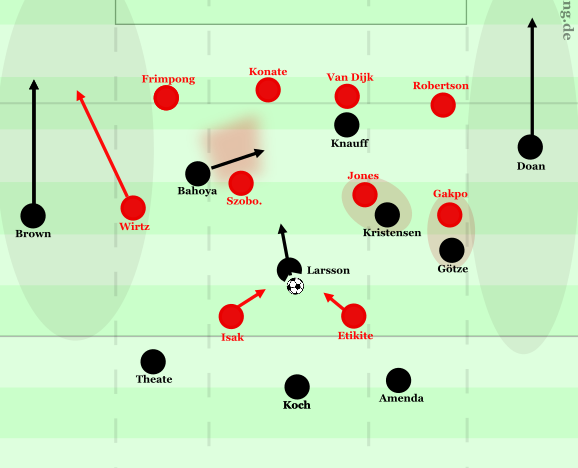

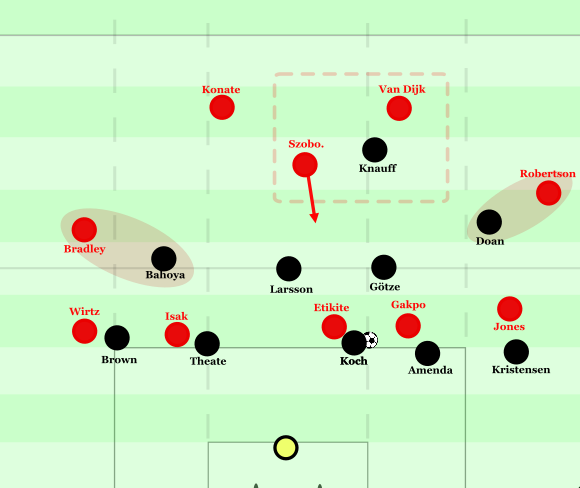

Frankfurt’s Switching Problem

Because Liverpool could switch the ball with ease, it was increasingly played from one wing-back to another. Personnel shifts were very dynamic: Jones, Wirtz, or Szoboszlai occasionally operated wide as wing-backs, while Konaté and Robertson advanced into the half-spaces. Switches could be executed directly through the half-space movements of van Dijk. The core issue for Frankfurt lay in the 5-4-1 block: ball-far wingers and full-backs tended to drift too far into the half-space. After Liverpool’s switches, these players moved relatively uncontrollably back into width to track their direct opponents.

At this point, the question arises as to why Frankfurt focused so heavily on blocking and, after deliberately allowing switches, responded in such a fragmented way by pushing out wide.

Jones Steps Out

This repeatedly created pockets of space between full-back and half-back that Frankfurt’s 5-4-1 block was supposed to prevent, but Ekitiké consistently sought and exploited them between Theate and Brown. The issue was compounded by the fact that, although Frankfurt tended to push out, the long pressing distance in width made it difficult to prevent Liverpool from seeking 1v1 situations. Brown was repeatedly placed under intense pressure in these duels, as diagonal pressing in a deep block is one of the most complex tasks: he needed to both close depth to block dribbles and runs from the half-space and defend the flank. Early on, however, Brown managed this reasonably well, and a subsequent ball win from him led to Frankfurt’s opening goal.

Frankfurt’s wide players increasingly dropped back during Liverpool possession to support the full-backs in loose numerical superiority pressing. Yet, Doan on the right frequently failed to isolate the backward passing lane, often losing track of Jones and Robertson, allowing Gakpo to break free and enable another switch. On the left, the rotational setup was less dynamic, but Gakpo was slightly more proactive than Frimpong (later Bradley) in taking on Kristensen directly in 1v1s. Initially, however, there was insufficient depth support, leaving Gakpo relatively isolated. Kristensen’s effective blocking of crossing options further limited the Dutchman’s effectiveness in these situations.

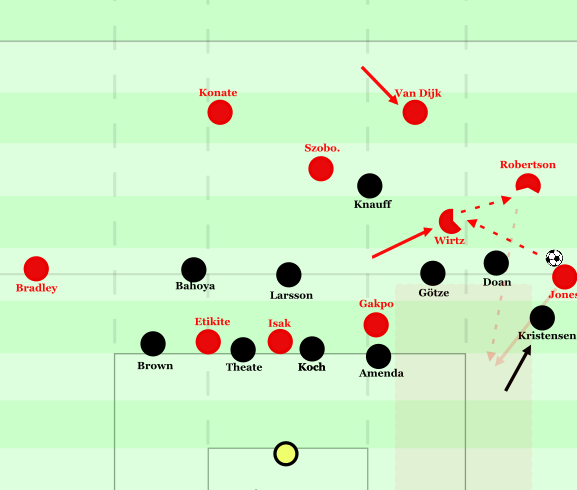

Higher wing-backs as the Key Point

After conceding, Liverpool pushed further forward, particularly in how their wing/full-back (depending on Szoboszlai’s temporary role in the back three) and number eights operated higher. Robertson and Jones increasingly formed a pair on the left side, while Gakpo moved more centrally in response to his earlier isolated position. Robertson pushed up as the left wing-back to free himself from Doan’s pressure and, together with Jones, create a 2v1 against Kristensen. This allowed Gakpo to repeatedly hint at depth in the half-space or actively position himself in the box—crucial since crosses had previously been only partially effective.

The width pair also allowed Doan to drop more frequently and shift from the half-space into wider positions, reopening spaces in the ball-side half-space. These were exploited primarily by Wirtz when diagonally dropping, forming a kind of dynamic trio with rotating coverage of width and half-space alongside Gakpo and Robertson. Typically, Wirtz, as the trigger for Phase 1 dynamics, dropped diagonally into the half-space and laid off to Robertson moving forward, while Jones pushed diagonally into the half-space center behind Wirtz, later being targeted by Robertson as the receiving player.

Dynamic Play with Wirtz

the center. This splitting of the back five deliberately opened up deep half-space channels behind Frankfurt’s defensive line. At the same time, the Reds often sought to occupy the ball-far full-back and half-back, creating central spaces. Isak exploited these spaces with diagonal runs, using his pace advantage over Theate effectively.

When these spaces couldn’t be played directly, Liverpool remained in motion. One of Liverpool’s key strengths is maintaining this dynamic play through constant rotation of width. For example, Wirtz moved wide when the deep ball didn’t arrive, seeking 1v1 situations against Kristensen. The Frankfurt defender struggled against the German, who consistently cut inside. Through these inverted dribbles, Wirtz repeatedly found half-space areas—often connecting with Jones or Gakpo, who were probing the space in front of the defensive line. Frankfurt’s defenders continued to struggle with decisions between stepping out and securing depth.

It also became clear that the wing-backs increasingly made overlapping runs when the wingers had the ball. For full-back Kristensen, this meant he no longer consistently engaged directly with the winger, often leaving the duel to Doan to track the ball, while he dealt with the overlapping runner. Consequently, Frankfurt’s lateral dueling became more passive, giving the winger more space and time on the ball. Simultaneously, channels opened centrally in front of the defensive line because Kristensen was occupied by the overlapping full-back and Doan’s wide diagonal drop failed to fully isolate the passing lane to the center. This allowed Liverpool increasingly comfortable ball circulation on the wings with central connection options, opening opportunities for shots from the edge of the box—especially for the number eights, who could join centrally and occasionally shoot from distance.

Inactivity Leads to Passivity

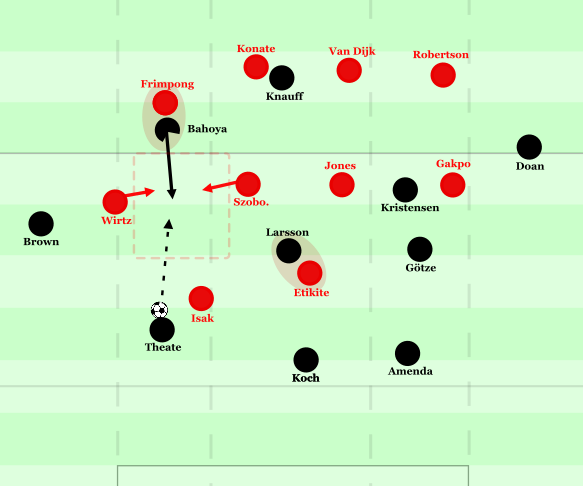

This increasingly prominent Liverpool dynamic, combined with Frankfurt’s continued failure to isolate backward passes, forced Frankfurt in the middle of the first half to operate deeper in their 5-4-1 block, constantly defending in a low posture. The original plan—to lure Liverpool out, provoke errors into the compact block, and then attack their rest defense on the counter—became progressively more difficult to execute.

Liverpool’s Rest Defense

This was largely because Frankfurt’s wide players, Bahoya and Doan, were increasingly drawn into defensive duties and had to drop deep, meaning they couldn’t provide the vertical width after winning the ball that they typically should as deep runners. At the same time, Liverpool tracked any vertical movements from Frankfurt’s wide players very effectively through their wing-backs; on the ball-far side (here Bradley), they aimed to anticipate the advance of the far-side winger and mark him with the far-side wing-back, making it difficult for him to break free.

Additionally, Liverpool used their deeper number eight—usually Szoboszlai—and van Dijk to double up on the ball-near attacker Knauff in the half-space, preventing him from being played into effectively, which worked well: Knauff struggled to hold the ball for wall passes after turnovers. Konaté covered any spaces behind this double, particularly for second balls. However, the underlying problem remained that blocking implicitly assumes winning the ball within the defensive line when defending deep. After ball recoveries, Frankfurt could hardly progress from the back against Liverpool’s immediate numerical overload, which instantly triggered overloading counter-pressing and closed off vertical passing options to the number eights—the weak point in Liverpool’s rest defense system. As a result, Frankfurt’s defenders were often forced into long balls under pressure.

In other words, even after going 1-0 down, Frankfurt continued to lose possession. Because they operated deeper, these turnovers occurred in more advanced positions of Liverpool’s pressing, creating direct pressure and limiting structured buildup. The space that needed to be covered on counters was larger than in the mid-block early in the game.

One could also discuss how a counter-attacking approach correlates with pressing and collective compactness. Frankfurt occasionally pressed individually and fragmentedly in response to certain cues (e.g., second dribbles in the half-space or wide distances), but lacked a clear, collective transition from the block into pressing. This allowed Liverpool to face minimal pressure in their first build-up line and develop their dynamic play, effectively freezing Frankfurt into passive blocking.

Andrzejewski et al. (2022), in Analysis of team success based on match technical and running performance in a professional soccer league, analyzed over 600 Bundesliga games across two seasons and correlated various performance indicators with team success. One key point: more duels won correlated with more counterattacks. Similarly, Lepschy et al. (2021) found in analyses of the 2014 and 2018 World Cups that teams with higher duel success and effective counters were more successful. These findings suggest that both the quality and quantity of duels are linearly linked to successful counterattacking.

At the same time, Liverpool created relatively few chances from open play. They generated five major chances, with two goals from set-pieces and one counter leading to a 3-1 halftime lead. Their main struggles were in finishing crosses and chance creation around the box. A side effect of their play around Frankfurt’s block was that much creative personnel was positioned wide, limiting their effectiveness in tight spaces. Players like Wirtz and Jones rotated around the block with the wide players, sometimes causing problems in small-sided scenarios inside Frankfurt’s compactness. These options were therefore missing in key areas.

Build-up should not be judged solely by whether it leads to goals but also by how it shifts game momentum. This increasingly shifted in Liverpool’s favor, largely due to their adjusted progressive play.

Second Half

After two corner goals just before halftime—each exploiting target players (van Dijk and Konaté) to find the “blind spot” created by horizontal movements of blockers like Ekitiké and Robertson—little else occurred in the first half. Liverpool continued to control the game against Frankfurt’s deep block, increasingly using direct diagonal switches to the far side to give their wide players more time 1v1 against Frankfurt’s ball-far full-backs or to create depth in the box.

These passes were occasionally imprecise, causing “ping-pong” situations in front of Frankfurt’s box around the central number eights. Liverpool faced minor counter-pressing problems but could usually manage them with collective back-pressing and tactical fouls.

At halftime, Arne Slot brought on Chiesa for Isak, and Liverpool increasingly adopted a clear back-three setup in a 3-5-2 with slight adjustments. Wing-backs Robertson and Bradley operated deeper in their starting positions, intending to pull Frankfurt’s full-backs wider and open half-space channels for the inside wingers Wirtz and Gakpo. Diagonal breaking movements—acting as connectors between wing-back and number eight—remained visible, particularly Wirtz on the right. During ball possession, he would pull Konaté out, quickly lay off to Bradley, and then exploit the space between Brown and Theate while moving in the “play & go” rhythm.

Liverpool in the Second Half

Overall, Eintracht also struggled in the second half to consistently track or cover the drops from their last line in front of the second block. This repeatedly created 2v1 overload situations for Liverpool in width. Theate occasionally pushed out slightly but could not exert meaningful pressure on Wirtz. Instead, he often opened spaces in behind, which Chiesa repeatedly exploited to be played directly in behind—often from passes by Konaté.

Direct diagonal balls to advancing wing-backs became more common, with these players benefiting from slightly deeper starting positions to gain a dynamic advantage over Frankfurt’s wide defenders (Brown in particular struggled against Bradley), allowing these balls to reach deep positions. The persistent issue, however, remained that Frankfurt struggled to get into the box.

Frankfurt offered very little themselves. Apart from isolated actions following ball recoveries that couldn’t be converted directly into counterattacks, little developed. Even during brief periods of higher possession, the team remained vulnerable to Liverpool counters. This was primarily because Frankfurt’s number eights continued to operate high, leaving the space in front of the first-second line rest defense largely uncovered. Fast attackers—especially Ekitiké—and the dribble-capable Chiesa consistently exploited these half-space channels in Liverpool’s secondary attacks.

Conclusion

The 4-1 goal came from a Liverpool turnover after Szoboszlai freed himself in the number eight zone with a dribble. Wirtz received the ball deep in the half-space between Brown and Theate. Gakpo drove forward from the space in front of Frankfurt’s number eights to the far post, exploiting the goalkeeper’s “blind spot,” and finished. (The goalkeeper’s blind spot is often an underestimated reference point for attackers.) The 5-1 was a long-range shot from Szoboszlai following a horizontal lay-off from the wide area into the half-space. Such lay-offs occurred frequently throughout the game but had rarely been finished consistently.

Overall, it was an interesting game—predictable in some ways but also grinding at times. Frankfurt must significantly improve their defensive activity and pressing to get back on track in the coming weeks, particularly against top teams. Liverpool, on the other hand, secured important morale-boosting points. The team showed clear potential for improvement, but also remained prone to errors. Overall, it was a favorable game for Slot and Liverpool.

MX made a name for himself in Regensburg with his tendency to overcomplicate the game. While flirting with the RB school, he remained a secret romantic at heart, drawn to Guardiola’s style of football.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen