Double analysis: Bodø/Glimt impressive against Manchester City and Atletico Madrid – MX

The Norwegians impress against two top European teams and draw attention to themselves. We take a look at the two matches.

Translations of German match analyses on spielverlagerung.de

Bodø/Glimt v Manchester City (3:1)

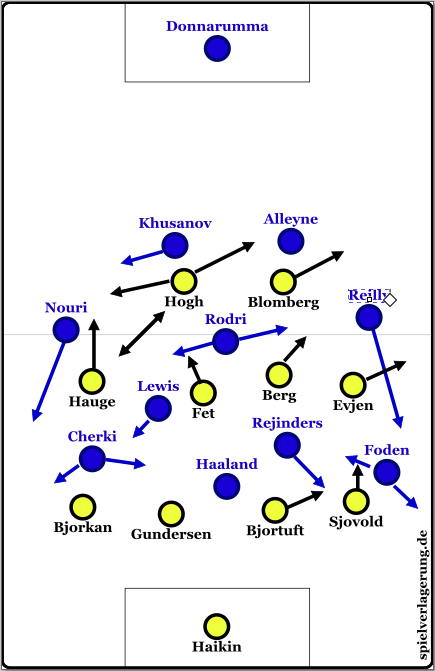

The Formations

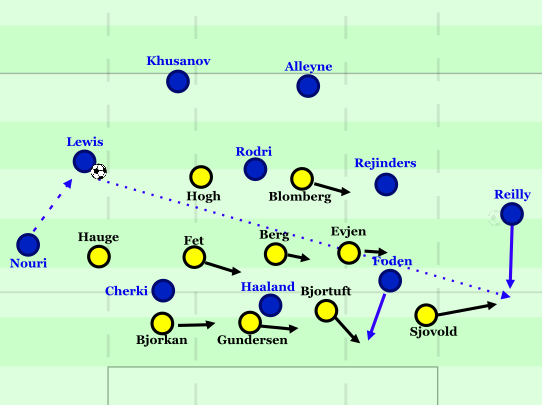

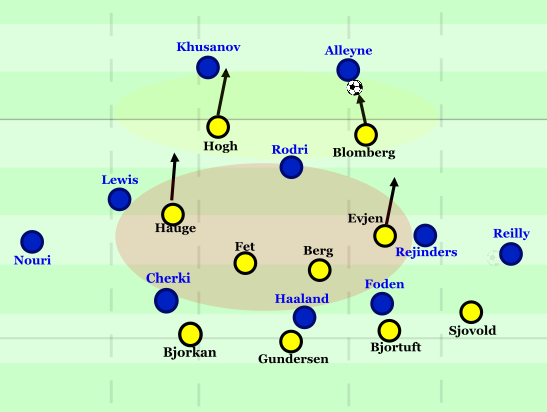

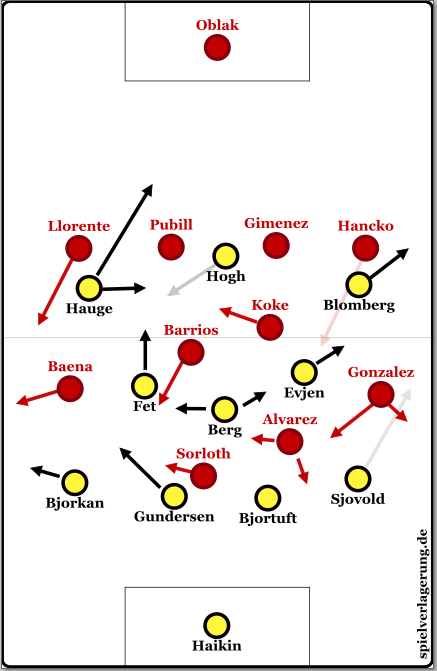

Bodø/Glimt have been regarded as a hidden gem within the analysis community for several years now, but at the latest since Tuesday’s success against Manchester City, clips of the Norwegian side have been flooding social media. For this notable achievement, the home team deployed a 4-4-2 base formation: Haikin operated between the posts, with Bjørtuft and Gundersen forming the centre-back pairing in front of him, Sjovold and Bjørkan as full-backs, while Berg and Fet played centrally. Evjen and Hauge occupied the wide roles, with Blomberg and Høgh forming the strike partnership. Due to the winter break in Scandinavia, the team are currently in the midst of preparations for the upcoming season; their last competitive match dates back to 10 December – a 2–2 draw against Borussia Dortmund.

City, by contrast, arrived after weeks of full workload and a derby defeat against United (0–2). In Norway, Pep set his team up in a 4-3-3: Donnarumma started in goal, with Alleyne and Khusanov as centre-backs and Reilly and Nouri as full-backs. Rodri operated as the holding midfielder, with Reijnders and Lewis as advanced eights in the half-spaces. Haaland played as the central striker, with Foden and Cherki operating around him. What led to the English side’s defeat at the Aspmyra Stadion?

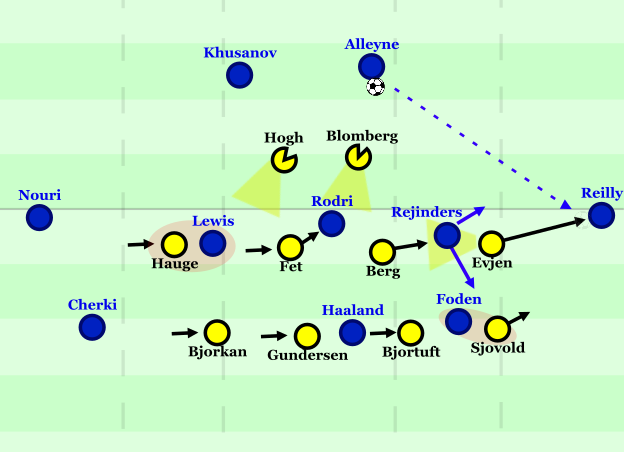

Premise of Forcing Play Wide

The home side initially organised themselves primarily out of a 4-4-2 midfield block, with the main focus being, on the one hand, to block the passing lanes into the holding midfield zone towards Rodri through the positioning of the two strikers, and on the other hand to also close the passing lane into the far-side half-space towards Manchester’s far-side eight, who was additionally marked by the far-side winger. At the same time, the inward movement of Bodø’s far-side eight provided further protection of the passing lane into the centre towards City’s holding midfielder Rodri. Through this double coverage, passes into areas in front of the Norwegian midfield were virtually impossible. This, in turn, allowed the ball-near eight and winger to push out while maintaining their base position in the half-space, creating a 2v1 against City’s ball-near eight and effectively isolating him. Overall, everything followed the premise of forcing play wide – which worked very well.

Initially, I was somewhat sceptical as to whether this idea would work, especially because Bodø’s wingers, positioned narrowly in the base structure, formed very lateral pressing angles against City’s extremely wide full-backs, which inherently carried a significant risk of being beaten via dribbling. On the left side, left-back Reilly was disappointing in this respect, showing little of the required tempo in his first touch or when driving forward to dribble past Evjen. Right-back Nouri did manage to beat Hauge via dribbling in isolated situations, but he simply lacked effective follow-up actions. One reason for this was the diagonal step-out defending of the Norwegian full-backs, which repeatedly blocked the passing lane in behind towards the advancing wingers Foden and Cherki, who were also tracked directly in their depth runs by Bodø’s centre-backs.

However, these horizontal pressing angles did not only entail potential problem areas but also produced positive effects. They isolated the horizontal pass into City’s eights, who repeatedly attempted to free themselves vertically behind Bodø’s wingers. Yet their movements into wide areas were well tracked by Bodø’s eights, and City were consistently forced towards the outside, leaving them with hardly any opportunities to attack depth. While City were occasionally able to access the half-space in front of Bodø’s full-backs, the stepwise outward defending of the full-backs combined with the lateral shift of the centre-back created a tight 2v3 situation against Reijnders and Foden, which cause

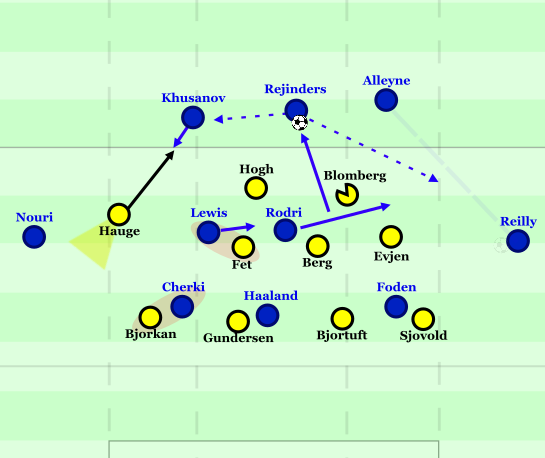

Bodo isolating Rodri

d significant problems. On the one hand, Foden struggled to free himself into the interior between-the-lines space against the numerical disadvantage versus full-back Sjovold and centre-back Bjørtuft, and therefore could hardly release Reijnders from pressure. Due to this static positioning at height, he also failed to draw right-back Sjovold out of the wide zone and was thus unable to open potential dribbling spaces for Reijnders. Reijnders, in turn, struggled significantly with the confined spaces and the immediate lateral pressure applied by Berg.

One could also raise a striker-related issue here, as Bodø’s ability to create a numerical advantage in the ball-near half-space through the step-out of the centre-back was partly due to Haaland’s very static central positioning, which allowed him to be marked relatively easily by the far-side centre-back. By shifting further into the half-space, the striker could have created a 3v3 numerical equality and, in doing so, opened more space for Foden to find separation between the lines. At the same time, the space between the Norwegian centre-backs was repeatedly exploitable and attackable in depth due to the step-out of the ball-near centre-back. However, Haaland rarely sought these runs. As a consequence, City often had to resort to backwards passing options to the centre-backs, which were mostly available because Bodø’s strikers dropped very deep in order to prevent potential solutions via Rodri as the holding midfielder and, more generally, to contain play in front of the midfield line.

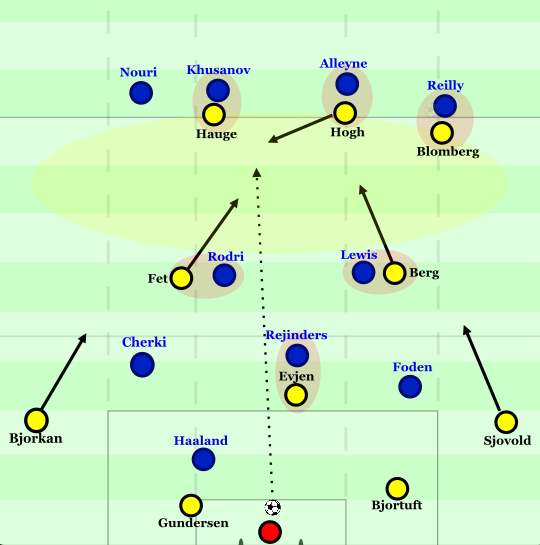

Temporary Back Three as the Key?

In light of the early issues, variations of a back three could be observed relatively quickly on the visitors’ side, with Reijnders and Rodri repeatedly dropping in between or alongside the centre-backs. In fact, one underlying idea behind this appeared to work: the strikers were no longer able to block the passing lane from the central centre-back into the holding midfield zone, allowing City to play through the space between the two forwards to Rodri at times. In the opening minutes, Bodø’s own eights were still somewhat slow to adjust, which allowed Rodri to turn between the lines on several occasions and, for example, play through to the advancing full-backs. After a few sequences, however, the Spaniard was simply marked more tightly when the back three was implemented; although he could still be found a few times, he was no longer able to turn due to the immediate pressure from behind.

For this reason, further positional adjustments from Rodri became increasingly visible, with him drifting more and more into the right half-space, positioning himself between Alleyne and Reilly as a connecting player and thereby occupying Reijnders’ initial position, while Lewis operated as the holding midfielder in the centre. Via the drifting Rodri, City were indeed able to access the width on the advancing Reilly on several occasions, particularly because right-sided striker Blomberg struggled to turn into his blind side after the pass and apply pressure on the Spaniard from behind. As a result, right winger Evjen often had to take over these outward movements, thus releasing the marking on Reilly, but due to Rodri’s outstanding quality in his first touch and overall balance, he could hardly prevent him from turning or playing out to the flank. However, Bodø benefited greatly from the fact that their own full-backs immediately stepped out onto City’s advancing full-backs, thereby preventing free dribbles in wide areas. Overall, Bodø displayed a very high level of judgement in deciding when the bypassed wingers could still access Reilly and Nouri and when a lateral step-out was necessary – preparatory scanning, particularly from Sjovold, should be explicitly highlighted here. As a consequence, Reilly struggled in dribbling situations against the directly stepping-out Sjovold and rarely sought 1v1 situations proactively.

Left-back Bjørkan should also not go unmentioned, as Nouri in particular posed a significant threat, especially through City’s back three in possession when the central centre-back – who was hardly pressed and therefore under l ittle time pressure – could play long diagonal balls out wide to the advancing Nouri behind Hauge. In these situations, Bjørkan showed tremendous pace, especially when turning towards his own goal, aided by strong pre-scanning to assess Nouri’s positioning and pick up the right-back’s depth run. As a result, he was able to match Nouri both in acceleration and top speed, prevent him from directly dribbling into the box, and force him towards the outside. Consequently, Nouri was unable, for example, to look for direct crosses towards Haaland, allowing Bodø to neutralise a potential source of dynamism for the English side.

ittle time pressure – could play long diagonal balls out wide to the advancing Nouri behind Hauge. In these situations, Bjørkan showed tremendous pace, especially when turning towards his own goal, aided by strong pre-scanning to assess Nouri’s positioning and pick up the right-back’s depth run. As a result, he was able to match Nouri both in acceleration and top speed, prevent him from directly dribbling into the box, and force him towards the outside. Consequently, Nouri was unable, for example, to look for direct crosses towards Haaland, allowing Bodø to neutralise a potential source of dynamism for the English side.

However, Nouri’s ability to free himself so easily behind Hauge also had a prior context, as Bodø placed strong emphasis on preventing right-sided half-back Khusanov, against City’s back three, from driving diagonally into the right half-space after switches of play from left to right, or from dribbling past the first pressing line formed by the Norwegian strikers. Accordingly, winger Hauge triggered the press on Khusanov. Presumably, this was also intended to prevent a more direct connection from the Uzbek to right-back Nouri or into the last line towards Cherki, and thus avoid a potential 3v2 overload on the right side – particularly because Khusanov would occasionally push forward after carrying the ball. A higher diagonal carry from Khusanov would have allowed him to dribble towards Hauge in the half-space or into the block, while Nouri could have freed himself wide on the right. The resulting shorter distances between City’s players would have significantly complicated (in temporal terms) the handovers within Bodø’s defensive line, and Cherki, in particular, could have tended to find separation between the lines, as Bjørkan would have had to step out towards Nouri. Overall, a compact block always relies on the opponent having long passing distances in order to gain time to shift; the Norwegians ensured this by isolating the key player in flat switches of play from carrying the ball on what was otherwise City’s combination-focused right side.

Triggering the press on the Uzbek, by contrast, meant that he was largely unable to carry the ball diagonally, while Hauge’s diagonal pressing angle also isolated the more direct wide connection to the dribble-strong Nouri, who could hardly be accessed after switches of play. As a result, he was scarcely able to exploit his dribbling speed in these situations. Accordingly, left-back Bjørkan was able to remain in his base position on Cherki, meaning that the latter could also not be found vertically by Khusanov in the half-space. Even when Cherki attempted to free himself at times, Khusanov rarely looked to play into the last line. The transition from a compact block to pressing triggered by a specific player thus proved to be a highly effective tool for Bodø, as it prevented both City’s quick flat switches of play via Khusanov and their combination play through ball-carrying half-backs.

The Pitfall of the Back Three

Despite pressing Khusanov after switches of play, City were still able at times to find a route to right-back Nouri, particularly when Lewis dropped in to the right of Khusanov. Overall, as mentioned, the focus during the frequent switches was simply more on preventing Khusanov’s ball carrying than on fundamentally pressing the right-sided half-back. In these situations, Hauge did not actively trigger the press; instead, Bodø largely remained in their block and then shifted the pressing focus towards the full-backs. In addition, Lewis himself tended to show little in terms of active ball-carrying movements, unlike Khusanov, and instead preferred to play directly towards the full-back. Taken together, this underlines the personalised focus on Khusanov rather than a general pressing of the right half-back, which consequently proved effective. There were also notable side effects for Bodø stemming from City’s implementation of the temporary back three.

Because City increasingly operated in a back three through a midfield player dropping in, the midfield was consequently reduced to a double pivot, or rather the eights positioned themselves more between full-back and centre-back as connecting players. As a result, they were hardly able to push up actively to occupy Bodø’s eights, especially since dribbling access through this zone was minimal in the early phase. Accordingly, Berg and Fet were now able to position themselves deeper in front of the defensive line, primarily blocking the passing lanes from the full-backs into the centre and picking up the dropping movements of the wingers, which Che

1v3 Against the Wingers

rki in particular increasingly showed towards the middle of the first half. Overall, the wingers now found themselves almost permanently in a triangle formed by Bodø’s full-back and centre-back, as well as the dropping eight. While there were occasional passes into Cherki, who was generally more active than Foden on the right, turning in these tight spaces was hardly possible, as Bodø’s triangle closed down immediately and shut off any potential dribbling lanes.

One is therefore almost inclined to argue that City’s wingers fell victim to a kind of fallacy. They operated conspicuously narrow and high for long stretches, presumably in an attempt to prevent Bodø’s full-backs from stepping out wide or to pin them in the half-space, thereby creating dribbling space for the full-backs. However, beyond the fundamental issues of separation and spatial congestion, there was also simply a dribbling problem on the part of the full-backs. This meant that stepping out by the Norwegian full-backs was not actually required, allowing them to remain tightly positioned in the half-space.

Nouri and Reilly nominally continued to hold an advantage against the horizontal pressing angles of Bodø’s wingers, but Nouri in particular displayed unusual issues with tempo in his dribbling and was unable to carry the ball far enough into wide areas from structured build-up. As a result, he was unable to dribble past Hauge, while the passing lanes into the half-space were simply too long to initiate play-and-go patterns with the depth runs of Nouri that had been visible in recent weeks. Although there were isolated attempts, Cherki, under immediate pressure from all sides, could only lay the ball back into depth very untidily (let alone turn), meaning that little benefit was ultimately derived from these situations.

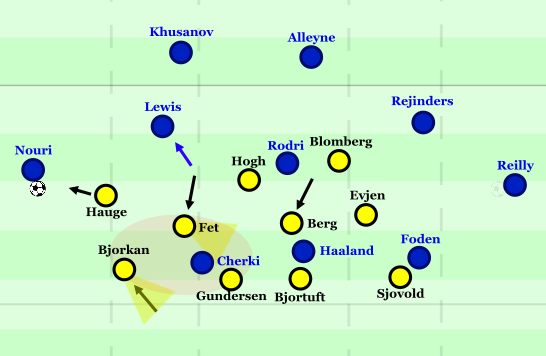

The Question of Dropping Movements

In principle, one can legitimately raise the question of why the eights Lewis and Reijnders increasingly dropped deeper during full-back dribbles, rather than stepping up into the half-space as in the opening minutes and thereby indirectly enabling Fet and Berg to drop back. One possible explanation is that this was intended to shorten the backward passing options in order to switch play more directly, particularly to further provoke Bodø’s shifting from their block or to gain time for dribbles in wide areas. Lewis, operating in the right half-space, repeatedly switched play with direct diagonal balls into the left flank towards full-back Reilly.

However, Reilly in particular continued to struggle in direct 1v1 situations against Sjovold, who, on the one hand, shifted extremely quickly into wide areas after switches of play and, on the other, adjusted his position anticipatorily already during Lewis’ ball circulation after backwards passes. As a result, the space between him and Bjørtuft was at times somewhat large, which Foden repeatedly attacked. In principle, it would also have been possible to play Foden directly in depth through Lewis in the half-space; however, Lewis rarely looked for these options, unfortunately from City’s perspective, even though Foden occasionally signalled for them. In isolated instances, Foden was found in depth via Reilly, but Bjørtuft immediately forced him wide, and there continued to be a lack of direct supporting runs from the centre for follow-up actions.

Lewis looking for switching the sides

In addition, Alleyne and Reijnders in particular lacked pace when carrying the ball, meaning that especially through flat switches via the left side, City were hardly able to dribble past the first block line and consequently struggled to find access between the lines. Instead, they repeatedly played out wide, where they were known to encounter difficulties. Notably, there was a clear improvement in tempo on the left side whenever Rodri dropped out, something he did increasingly less as the match progressed. In isolated situations, he was even able to dribble directly past the first block line and thereby force Evjen to press out, which in turn opened up direct passing lanes to Foden. This was arguably the best way to bring Foden into play, and Rodri was also able at times to lay the ball off effectively to the now free Reilly out wide, from where occasional free crosses were delivered, resulting in sporadic box actions.

Another explanation for the dropping movements could be that City aimed to draw Bodø’s eights out of midfield in order to open diagonal passing lanes from the full-backs into the last line towards Cherki or striker Haaland. However, Bodø’s eights simply did not follow these movements outward; instead, they focused on dropping back in a blocking manner to close the space in front of the defensive line, thereby largely preventing play into these zones. Overall, the block height did drop due to this extensive retreat of both midfield and, consequently, the forward line. Yet, particularly after City’s backwards passes, Bodø shifted up collectively again and re-established themselves in a mid-block, thereby reducing the space between the forward line and City’s first build-up line.

Høgh counters for the double strike

The stepping out proved decisive in another context on the evening, as Høgh’s double strike (22nd, 24th) came from counterattacks in which Bodø had already shown clear strengths during the match. These situations were prepared by the fact that most of the long clearance actions after ball wins in the defensive line were played towards Manchester’s centre-backs, who were immediately pressed aggressively by the strikers – with Blomberg in particular sometimes speculating on the ball win and thereby directly putting Alleyne under pressure. Rodri was hardly able to track the immediate supporting runs in the resulting 1v2 situations, partly because he showed noticeable problems when adjusting orientation after changes in play direction and was disadvantaged in acceleration against the strikers. As a result, the centre-backs came under significant pressure in aerial duels, and any resulting second balls mostly ended up with the strikers.

Furthermore, due to the dropping of the eights, there was no direct access to second balls in the half-spaces, allowing Bodø’s immediately supporting wingers to repeatedly collect City centre-backs’ imprecise headers. The half-space in front of the defensive line therefore proved extremely vulnerable to second balls after clearances. Overall, City were frequently even or outnumbered centrally in and around the box following Bodø’s counterattacks, due to the hardly occupied centre behind holding midfielder Rodri. Their defensive behaviour became reactive and swarm-like: the initial aim was to get as many players as possible centrally behind the ball, with attention almost solely on the ball or the near post. Given the high tempo of Bodø’s strikers when dribbling after winning second balls, as well as the rapid delivery of crosses to the far post (demonstrating the Norwegians’ preparation), Bodø were able several times to exploit City’s intuitive defending at the far post, where Høgh was positioned, while simultaneously exposing a structural weakness of goalkeeper Donnarumma. The anticipatory keeper often positions himself strongly towards the near post, and with crosses into his blind spot he struggles to turn quickly due to a relatively weak movement pattern – exactly the space that Høgh consistently exploited.

After the initial shock for City, they showed somewhat more courage in build-up, increasingly seeking Cherki and Foden directly in the half-space via the full-backs, despite the immediate pressure from behind. Foden in particular was occasionally able to turn against Sjovold, who showed early signs of fatigue towards the end of the first half, and on occasion penetrate into the box. His deliveries, however, were not dangerous, as they were mostly low crosses into the deep spaces, which Bodø’s dropping eights could comfortably intercept. Cherki was also sought more selectively, but often still laid the ball back to Nouri, as Bjørkan defended very aggressively and left Cherki little space to turn in the right half-space. Overall, there were also slightly more chip balls into the half-space from the half-backs in the back-three build-up towards the advancing Foden or Reijnders, who were rotating more frequently. The space between Bodø’s centre-backs could be attacked on a few occasions, but Bjørtuft continued to track these deep runs in the right half-space very closely – showing good acceleration when turning to follow – and repeatedly prevented dangerous shots.

In the increasingly open game, Bodø continued to create chances, both from transitions following clearances – around the 30th minute Høgh nearly scored at the far post to make it 3–0 – and also after goal kicks in deep build-up, where the team repeatedly regained stability and won the ball. Overall, Bodø focused heavily on playing long balls into the centre from their 4-3-3 against City’s 4-2-3-1 pressing in attack. These were secured either via the diagonally inward-moving eights Fet and Berg or through Høgh’s dropping movements in the half-space on the second ball. The focus of these long deliveries was less on immediately reaching depth, and more on securing the second ball and then counterattacking – something City continued to struggle with both in aerial duels between the centre-backs and in tracking Bodø’s advancing eights.

Bodø/Glimt engaged in counter-pressing even in their deep build-up phases.

This pattern persisted throughout the match: City’s centre-backs won only two out of seven aerial duels, with Khusanov in particular struggling massively against Hauge or, in rotation, against Høgh. Through these matchups against Khusanov, Bodø were often able to lay the ball directly into the half-space to the inward-moving eights and then, via their dribbles, attempt to play in depth to the advancing strikers – fundamentally similar to their counterattacks. Goalkeeper Haikin should also be mentioned, as he played very good and accurate balls into the centre or to target players, forming the foundation for Bodø’s counterpressing game. Once again, it is worth highlighting how important the consistent diagonal inward movement of the defensive line – particularly the full-backs – was for Bodø. This gave the eights and strikers immediate support as well as clear backward passing options whenever direct play into depth was not possible. Repeatedly, Bodø were able to secure possession this way and prevent City from launching direct counters – for example after ping-pong situations inherent in counterpressing – by targeting Haaland, Cherki, and Foden directly. This strong focus on counterpressing led City’s midfielders in the closing phase of the second half to position themselves progressively deeper in order to close the space in front of their defensive line.

Bodø exploited this adjustment by increasingly playing out flat – particularly via LCB Bjørtuft. His direct opponent, Foden, often found himself in a 1v2 against him and RFB Sjovold, and from his wide base position frequently executed imprecise curved runs. As a result, Bjørtuft was able several times to bypass Foden and lay the ball off to RFB Sjovold. Sjovold in turn could play vertically to the drifting eights Berg or Fet, who rotated situationally and freed themselves from the now (perhaps too) early-dropping Lewis into wide areas. There, they could carry the ball into dribbles without immediate opposition and occasionally initiate depth play to the strikers.

Around the 39th minute, Hauge acted as the dropping player with Høgh as the target, and indeed Høgh found the dropping Hauge via a header. LCB Alleyne did not track Hauge’s movements between the lines directly – something he increasingly did overall to form a 2v1 against the target player, which nevertheless had little effect, while City lost access to the half-space. The deeper eights did not pick up the dropping strikers (for example, Rodri completely failed to check the runners behind the strikers). Consequently, Alleyne was at a clear dynamic disadvantage after Hauge’s layoff and could hardly influence his dribble. Høgh immediately pushed forward after the layoff and was able to take a shot at the edge of the box – but narrowly missed.

Second Half

Accordingly, Bodø went into the break with a deserved lead – even if the scoreline could just as well have been 3–0 or 2–1. The match became more open, but this mainly benefited the transition-strong Norwegians. In the second 45 minutes, Manchester City increasingly introduced rotations between the eights and the full-backs, which did bring a noticeable increase in 1v1 quality out wide. Reijnders in particular, operating on the left flank, was able to provide occasional sparks against the increasingly struggling Sjovold and generate the first dangerous shots through inverted dribbles. Overall, there was also more dynamism from the wingers, who now repeatedly dropped into the half-space between full-back and centre-back. This brought more 1v1 quality against Bodø’s wingers as well as dribbling tempo, which had been lacking in the first half. City were thus able at times to dribble past them and situationally create 2v1s against Bodø’s full-backs. This increasingly led to crosses into the box towards Haaland, who, however, was unfortunate on the day, particularly with his runs towards the near post. As a consequence, Bodø adapted, with right winger Evjen increasingly dropping into the defensive line to form a 5-3-2, making it difficult for City to break through out wide.

Bodø, by contrast, continued to set accents on the counter, where City remained extremely vulnerable with their centre-backs against long balls and against the half-space runs of the Norwegian wingers. City’s midfielders were still largely unable to track these movements directly, allowing Bodø’s wide players to push through repeatedly and further stress City’s defensive line. In this context, Evjen would have broken through in behind in the 52nd minute and slotted home for 3–0, but the goal was disallowed for offside. Six minutes later, however, the breakthrough did come following a kick-off situation and counter-pressing sequence from Bodø: after winning the ball in the centre, the second ball following a dribble ended up with Hauge out wide, who drove inside in front of the defensive line. With Alleyne acting too passively and failing to step out, Hauge calmly finished to make it 3–0. Two minutes later, City did pull one back through a long-range effort from Cherki, as Bodø, now increasingly operating deeper in a 5-3-2 / 4-4-2, partially lost control of the space in the half-space in front of the defence – particularly because their three-man midfield became much narrower. However, two minutes later the lights were effectively turned out again following Rodri’s red card. Although Rodri actually had slightly more freedom in the second half due to Bodø’s growing fatigue and the resulting tracking issues in direct duels with their eights, and was able to turn well between the lines on a few occasions, his passing towards the wingers remained inaccurate. He was unable to play directly into their feet, meaning that they still struggled to turn in the half-space.

Conclusion

For some time now, I have been haunted by the thought that Pep might once again be running into an old problem: does his team have an issue when going behind, as was the case years ago? No team in the Premier League has collected fewer points after falling behind (zero), and overall Pep Guardiola’s side appears increasingly less resilient. Particularly immediately after conceding goals, they sometimes lose their composure quite markedly. This worries me more for the Citizens than the defeat itself against a very strong Bodø/Glimt side, who were extremely well prepared for this match and, under special conditions in Norway, were also clearly fresher. Nevertheless, this was a remarkable result that did not come out of nowhere. City, by contrast, once again move a little closer to the fundamental questions of recent months. Even if this match could be dismissed as a slip-up amid victories against Wolves, Galatasaray and Tottenham (alongside the derby defeat against United), it should still serve as a clear warning sign.

Atletico Madrid v Bodø/Glimt (1:2)

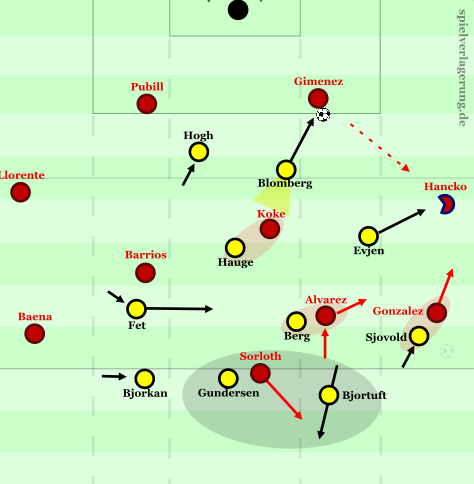

Atlético Struggle Against 4-1-3-2 High-Pressing

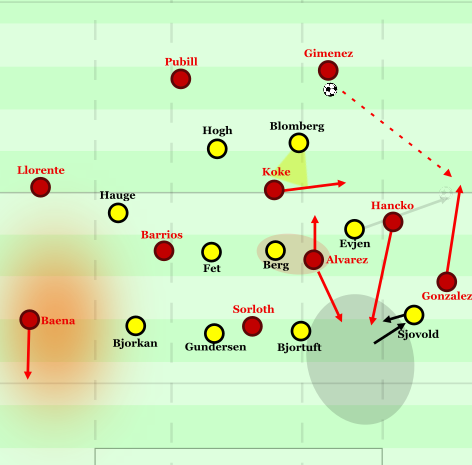

At the beginning of the match, the Rojiblancos initially built more frequently on the left side via Giménez in their deep 4-3-3 structure, with nominal striker Álvarez, compared to the standard 4-4-2 formation, moving alongside Barrios into the number ten zone. The main focus of the Norwegians in their 4-1-3-2 setup was, on the one hand, to isolate the passing lanes into the centre to holding midfielder Koke via a tight double-stroke from Høgh and Blomberg and to closely track his horizontal free-running movements into the half-space through Hauge. Additionally, Koke generally showed too little pace in these free-running movements and was hardly able to break free from Blomberg’s coverage shadow – effectively removing the holding midfielder entirely from Atlético’s build-up.

Through the half-space positioning of right winger Evjen, direct vertical passes from Giménez to number ten Álvarez were also prevented, which was essential, as holding midfielder Berg sometimes shifted too late into the half-space on Álvarez, allowing him to offer himself freely at times – yet he remained unplayable due to the close positioning of Evjen. By pushing the far-side striker Høgh forward, Bodø additionally kept Giménez occupied on the left side, preventing both flat switches to the right build-up side and backward passes to goalkeeper Oblak, who is generally only sought if no direct opponent can press vertically; consequently, Giménez mostly turned to left-back Hancko.

Hancko therefore faced major problems in direct duels against right winger Evjen, who overall demonstrated an excellent balance between maintaining his coverage shadow in the half-space and directly pressing Hancko. Particularly noteworthy were Evjen’s preparatory shoulder checks before pressing on Hancko, which he used to verify whether Berg had already closely marked Álvarez. The Madrid left-back consequently struggled to turn, as he not only adopted a too lateral position when receiving the ball – forcing him to open up widely on the first touch and lose momentum – but also had to swing his left foot very far in order to play vertical passes from this position.

Bodo/Glimt in High-Pressing

At this timing issue was compounded by the fact that, from his too lateral position – which is actually intended to provide a passing option to Koke in the holding midfielder zone – he had very little overview of vertical passing options ahead due to the limited line of sight. Koke was not only in Evjen’s coverage shadow but was also closely tracked by Hauge during his drifting movements. As a result, Hancko often scanned forward somewhat hastily at the moment of receiving the ball, repeatedly misjudging Evjen’s diagonal runs and incorrectly assessing both his intensity and distance. This ultimately led to turnovers near the sideline, especially since he rarely played directly to winger González, who was tightly tracked by right-back Sjovold.

Overall, Atlético Madrid tends to avoid playing directly into pressure over short distances – such as in these situations out wide between Hancko and González – likely also to prevent potential numerical disadvantages from backward pressing. In this instance, however, such an approach might still have been a useful option to relieve Hancko from his problematic position, especially as González possesses the technical quality on the first touch to turn inward with a direct opponent on his back and combine “play & move” with number ten Álvarez.

Sørloth Finds No Space in Depth

A related issue was that Atlético Madrid struggled greatly to create deep running lanes for Sørloth, meaning Hancko was hardly able to play long balls into depth. This was partly because number ten Álvarez was picked up by holding midfielder Berg, rather than right centre-back Bjørtuft stepping out on the Argentine, which meant that the centre-back neither opened passing lanes behind him nor positioned himself anticipatively to cover diagonal runs by striker Sørloth into the half-space. Consequently, Sørloth was effectively trapped in 2v1 situations, making aerial duels extremely difficult for the Norwegian international striker.

Berg’s ability to track Álvarez without opening significant central spaces in front of the defensive line was largely due to the wide stepping of left winger Fet, who was also able, situationally, to cover Sørloth’s dropping movements between the lines (when he rotated with one of the tens). For Bodø/Glimt, it was therefore crucial that the centre-backs did not open space behind themselves by stepping out, but that these movements were always managed through the midfield. Fet’s far-side inward movement did create a numerical disadvantage on the opposite side, but this could not be exploited by Atlético due to the far-side striker stepping up.

After the initial problems, Hancko increasingly avoided turning with the ball and instead attempted more inward dribbles into the half-space, allowing him on several occasions to dribble past Evjen, who despite his generally high pressing intensity sometimes did not fully press through and thus could not control the inward-moving left-back. However, the issue from Hancko’s perspective was that striker Blomberg acted very actively in backward pressing, and Fet’s inward movement also played a role here; simultaneously with the inward dribbles, Sørloth sometimes dropped between the lines and was marked by Fet.

Due to these ongoing problems, Atlético increasingly played long from goal kicks, but backward pressing also influenced this. The width of Bodø/Glimt’s full-backs made it difficult to regain second balls, which Sørloth often lost in the air due to being outnumbered, and allowed Bodø/Glimt’s wingers to turn directly and launch counters. Only through the direct compacting of Pubill and Giménez were the direct deep channels to target striker Høgh repeatedly closed – yet even then, the home side’s vulnerability was apparent early on.

Highlights from the Counterpress

Similar to Bodø/Glimt in attacking pressing, Atlético Madrid in their 4-4-2 midfield press from a compact base initially aimed to block direct passing lanes from centre-backs Gundersen and Bjørtuft to the wide players out to the flanks. The primary goal was likely to prevent Bodø’s typical triangle play, such as lay-offs from the wingers directly into the half-space to the eights – and in principle, Atlético restricted this directness very effectively.

However, full-backs Sjøvold and Bjørkan adapted to the compact positioning of the opposing wingers and increasingly operated flatter within the first build-up line of Bodø’s 4-3-3. This created very long and diagonal approach paths for Barrios and González toward Bjørkan and Sjøvold, limiting their ability to apply pressure and press through effectively. While Atlético thus isolated the diagonal passing lanes from the full-backs into the half-space to the eights Evjen and Fet and closely tracked the wingers’ minor free runs laterally, this indirectly still allowed Bodø repeated access to the eights. The eights repeatedly moved diagonally behind Atlético’s defensive line, while Koke in particular faced athletic difficulties in sprinting to track Evjen’s drifting movements. As a result, Evjen was repeatedly found with excellent long balls from Sjøvold behind Hancko, forcing Giménez to step out and cover to disrupt Evjen’s dribble. However, since Evjen struggled to dribble with his weaker right foot against the physically superior Giménez, Atlético was initially able to prevent significant breakthroughs from Bodø.

This was also partly because Bodø/Glimt were again able to create decisive second-ball situations against Atlético Madrid. Among other factors, this was due to Barrios and Koke in Madrid’s centre dropping slightly too far directly in front of their own defensive line on the Norwegians’ long balls into depth, which reduced their ability to contest second balls in the centre. Koke’s hastened dropping was likely partly due to loosely tracking Evjen’s drifting movements (despite passing him on to Giménez), with a tendency to move diagonally, while Barrios was dropping deep because he tracked wide inward movements of left winger Hauge into the centre. At the same time, this caused the two eights to move further apart, opening the central space, which the far-side eight Fet exploited by moving inward and securing multiple second balls. This also frequently opened a direct vertical passing lane to striker Høgh, who, while somewhat static in the structured build-up, effectively occupied left centre-back Pubill and prevented him from stepping out to challenge Hauge’s inward runs into the centre, while also pulling Barrios back.

Counterpressing = Playmaker

From these backward approach angles, Barrios was barely able to apply active pressure on the technically very strong Hauge, especially in tight spaces like the half-space, because Hauge already positioned himself horizontally in his base position. This allowed him to sometimes dribble horizontally into the centre and was often only stopped through tactical fouls. He tended to find the vertical passing lane to striker Høgh too rarely, despite Høgh signaling these runs several times and being well-positioned in the large gap between Pubill and Giménez – a drawback of horizontal dribbling: the view into depth is not immediately open, and shoulder checks while dribbling at this tempo are sometimes too complex. Nevertheless, the dribbling itself created dangerous situations, often requiring tactical fouls to stop him – for example, Koke, who moved back supportively, decisively blocked Hauge’s lateral passing lane to the eight Evjen.

Striker Høgh, however, was able to create some moments via wall passes, especially from Fet’s lay-offs, because Pubill struggled to step out and challenge him directly, allowing Høgh to turn toward the opponent’s goal with his first touch multiple times and either take shots from distance or play vertical passes into the half-space to the wide players.

Bodø/Glimt’s main strength, however, was the high residual pressing from the double striker duo of Sørloth and Álvarez, which very effectively prevented back passes to the centre-backs. This repeatedly forced Bodø’s full-backs into more direct play, meaning the Norwegians often lacked a consistent rhythm in possession. It was therefore unfortunate that the Norwegians could not transfer intensity through the wide players’ long runs, and also could not exploit the strikers’ high positioning during transitions due to problems in counterpressing. The pushing up of Bodø’s eights could have created spaces in transitions, but these opportunities were largely unused.

The strikers’ transition potential did manifest particularly after corners, when Bodø/Glimt did not deploy a specific deep cover player and, after losing the ball, occasionally dropped too far. This created pockets of space between the lines, particularly for the dynamic Álvarez. In the 8th minute, goalkeeper Haikin saved a shot after a transition following a corner and a header from Sørloth. Overall, the goalkeeper showed a solid performance, especially on the line and with his highly agile movement, particularly against headers to the far post.

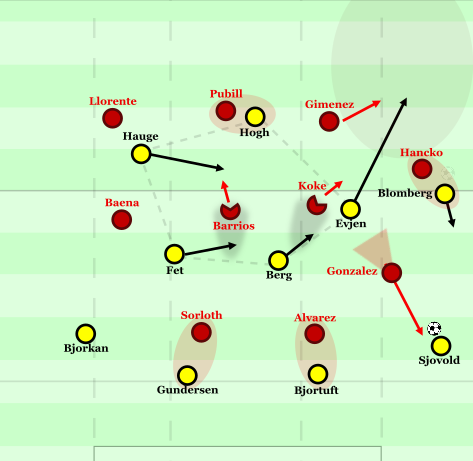

Atlético Finds Rhythm in a 2-3-2-3

Even before the opening goal in the 15th minute, Atlético Madrid increasingly found their rhythm, particularly through their higher 2‑3‑2‑3 build-up play. Compared to the match against Manchester City, the Scandinavian visitors struggled significantly more with the movements around Atlético’s 4‑4‑2 midfield block. The foundation of their left-sided build-up was the half-space base position of left-back Hancko, who, during possession, frequently moved directly into the half-space. This movement occasionally destabilized Atlético’s block. On the one hand, right-back Sjøvold in his base position pushed out too far laterally, creating spaces between him and Bjørtuft that Hancko exploited with deep runs in the half-space. Sjøvold generally noticed this too late and repositioned himself sluggishly, meaning he could only attempt to engage the advancing Hancko from behind, putting him at a severe disadvantage in the sprint duel. One could also question whether Sjøvold was too man-oriented on González, which caused him to lose overview of the half-space during scanning and also delayed the handover communication between Evjen and Sjøvold.

Baena as a Switching Option, Sjovold Opens the Depth

From Atlético’s perspective, winger González struggled to exploit Hancko’s forward runs into the half-space and could hardly play clean vertical passes to the Slovakian. While technically capable of turning immediately towards goal on his first touch, he missed several vertical passing options to Hancko—partly due to hesitation and partly because of technical limitations in the central passing game. Later, there were also rotations in role assignments between Hancko and González, with the initial right-back playing several very good vertical passes into the half-space for González, allowing him to penetrate the box multiple times.

Interestingly, Hancko sometimes only made his runs into the final third after González had played in the half-space, forcing Bodø/Glimt to adapt. Right-back Sjøvold then defended directly on González, while right-winger Evjen had to cover Hancko’s overlapping run. By pulling Evjen out of the midfield, the initial purpose of Hancko’s overlapping runs became clear: it opened the passing lane from González into the half-space to number ten Julian Álvarez. Álvarez repeatedly dropped from his advanced position into the half-space, and Berg struggled to track these movements from his blind spot, enabling the Argentine to initiate multiple dribbles between the lines—particularly when turning directly toward the center.

Bodø/Glimt clearly had problems when Hancko’s indirect movement blocked Evjen from pushing out laterally on González, as Evjen’s route was physically obstructed by Hancko’s base position. Consequently, Evjen had to follow Hancko’s run, which freed up the space between the lines—space that Bodø normally barely exposes. Álvarez’ dribbling also tied up Berg, allowing central midfielder Koke to move freely in the six-yard space and be sought out by the Argentine. From this area, Koke played several chip balls into the box—most notably in the 12th minute, when Atlético seemingly scored the opener through Baena after a chip from Koke, which was ruled offside.

One could therefore argue that Atlético could have shown a bit more willingness to play indirectly on the right side overall. In general, Berg and Fet were heavily occupied by Atlético’s number tens, maintained a deeper base position, and could not push out from the midfield block onto Koke. This increasingly meant that the double striker line focused less on pressing Atlético’s center-backs and clearly concentrated on blocking passing lanes to Koke.

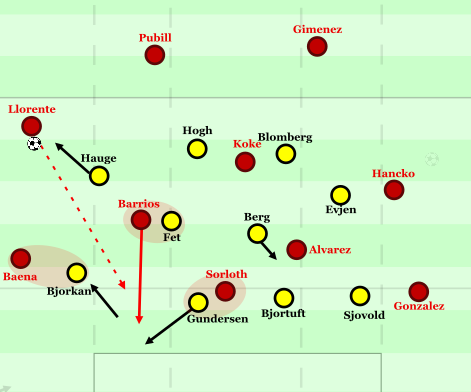

Problems on the Left Side

This lack of pressure on Giménez and Pubill meant that Giménez in particular was able to play several diagonal switches to the right winger Baena after returns from González/Hancko and thereby attack the wide, far-side inward movement of the Norwegians. Bjørkan, the left-back, proved extremely vulnerable to switches into his back toward the advancing Baena and had major balance problems, especially when turning in the flight path. As a result—particularly due to Baena’s high quality in receiving long passes and maintaining tempo—he had hardly any control over the winger and lost out several times.

Hauge did show active counter-pressing and attempts at overload pressing on Baena, but from his half-space base position he was on one hand hardly able to isolate the return passes to left-back Llorente, so the pressure from the counter-pressing remained overall rather low. In addition, he had a very long counter-pressing distance, so Baena was often simply out of reach due to his speed. Baena occasionally sought the return pass to Llorente, who, precisely due to Hauge dropping back, received a lot of space, showed some good inverted dribbles into the half-space, and from there found Álvarez between the lines.

Bjørkan stepping out also repeatedly opened vertical lanes for No. 10 Barrios in the half-space, where he was found several times near the edge of the box. Gundersen blocked him from delivering crosses on multiple occasions, yet Barrios occasionally provided dangerous balls, particularly to target man Sørloth in the box. Llorente also excelled in wide positions – which he occupied far more frequently than, for example, Hancko – with his vertical passing (notably, he requires very little wind-up for precise passes, which also benefits his timing) and repeatedly combined with Barrios or, in rotation, Baena in the half-space. This was also facilitated by Bjørkan repeatedly – similar to Sjøvold on the right – stepping too aggressively into width, thereby opening the vertical lane in the half-space that Llorente exploited.

Hauge tended to be somewhat sloppy in his approach angle and positioned himself too high in the starting position, which made his angle too lateral and limited his ability to isolate Llorente’s passing lanes into the half-space. Gundersen was able to lift his marking on Sørloth in time, block free runs in the half-space, and usually force Barrios wide, yet Atlético still occasionally found paths into the box through these mechanisms. Sørloth’s exchanges between the center-backs and Gundersen’s stepping out prevented worse outcomes. The 1–0 eventually came after a Llorente switch, which preceded a vertical pass to Baena. Through Álvarez between the lines, Atlético subsequently reached Hancko in the left half-space, who then served Sørloth in the box for a header.

Equalizer before halftime

After going behind and noticing increased vulnerability between the full-backs and center-backs, Bodø/Glimt began defending less aggressively on the ball and initially remained zone-oriented in the half-space. This largely blocked direct vertical passes through Atlético’s full-backs. Although the Spaniards occasionally sought balls over the last line, these were cleared – also due to Barrios and Álvarez’ aerial weaknesses. Bodø/Glimt frequently secured second balls in direct duels, aided by Berg’s excellent defensive coverage in front of the backline.

Atlético adjusted accordingly:

-

Right No. 10 Barrios: Barrios now dropped less into the half-space but positioned himself more in front of Bodø’s midfield block to create passing options for Llorente. This generated potentially interesting angles from the half-space – for deep runs by Sørloth or Álvarez dropping between the lines. While Barrios initially managed to disengage from Fet in these positions, Fet aggressively stepped out on the ball, consistently blocking all vertical options. There were some effective “play-and-move” sequences between Barrios and Llorente, but Hauge tracked Llorente’s runs tightly, preventing direct vertical connections.

-

Striker Sørloth: Benefiting from Barrios’ deeper positioning, Sørloth operated more on the right half-space. Barrios rarely found him, but Llorente could occasionally serve him in the half-space due to Hauge’s inconsistent tracking angles. The Norwegian striker frequently laid the ball out wide to Baena, initiating vertical dribbles. However, his frequent drifting left Atlético lacking a key target in the box.

-

Left-back Hancko: With Bodø increasingly focusing on spatial coverage and cleaner passing lanes in half-space runs, Hancko acted more traditionally as a wide full-back. From this broad position, Giménez occasionally bypassed Hancko’s direct opponent Evjen, yet Hancko lacked the first-touch speed and dribbling ability to exploit numerical advantages. Occasionally he enabled González to dribble wide, but overall, especially in deep positions, he was increasingly constrained. In the final third, he continued to rotate situationally with Álvarez, producing dangerous box opportunities, though Álvarez could have sought goal attempts more often. Central passing options remained limited, as Sørloth was somewhat static and primarily focused on crosses.

Atlético’s difficulties created insecure situations for Bodø/Glimt, particularly in the half-space through advancing central midfielders. Berg consistently secured second balls, and this persistent dribbling forced Atlético’s center-backs to step out, as Barrios and Álvarez had limited access in the half-space due to high starting positions and backward movement, while Koke had to centralize. This opened lanes in the half-space for deep runs from Bodø’s wingers and strikers, with Hauge exploiting the left half-space and Høgh frequently targeting the far post, similar to their approach against City. Hancko tracked Høgh closely and prevented several headers, yet it was ultimately a second-ball recovery and a cross – this time to the far post for Sjøvold – that led to the equalizer. One could argue that Atlético’s focus on defending the box may have left the space in front of the backline partially neglected, especially by deep-lying Koke.

Høgh strikes again

The remainder of the first half saw limited action; there were occasional chances for both sides, though Atlético maintained the upper hand. After the break, the balance shifted slightly, with Bodø/Glimt increasing intensity. Hauge returned as a second striker alongside Høgh, allowing more active pressing on Pubill and Giménez after passes than was the case with Høgh and Blomberg in the first half. Through this transitional pressing, Bodø effectively blocked diagonal passes from the center-backs, which could otherwise have posed systemic threats. Hauge’s role as a second striker after ball recoveries was crucial: operating as a “floating” link between the lines, he was often directly served by the central midfielders and looked to dribble between the lines. Koke struggled to contain this as a deep-lying midfielder, as seen in the 48th minute when he left Evjen open outside the box after a dribble – the resulting long-range shot narrowly missed. Counterattacks increasingly played a central role due to their relieving effect.

Atlético subtly adjusted as well. Right-back Llorente took a more offensive starting position, already hinted at in the first half, requiring Bjørkan to cover him directly. Bodø also moved Fet to left-wing – a position he was less comfortable with – sometimes pulled out of the half-space by Llorente’s lateral movements. This opened the lane from Pubill into the half-space for Baena or Álvarez, who rotated into these positions. Berg then stepped improvisationally into the half-space to block central dribbles, committing tactical fouls when necessary. Around the 50th minute, Atlético responded to Bodø’s adjustments with a back-three build-up. This partially limited Bodø’s transitional pressing, as the wide center-backs had to cover pressing paths, and the Norwegian team grew fatigued, stretching their movements. Some diagonal switches were still possible. Bodø benefited from the slight timing disadvantage in Atlético’s back three, while narrowing the distance on the far side. Overall, the adjustment’s effect was less significant. The personnel changes with more withdrawn full-backs were generally ineffective, as Llorente lacked first-touch speed compared to Baena, slowing down the game’s dynamics.

Although Bodø had less possession, when they had the ball, Atlético’s vulnerabilities reappeared. The go-ahead goal in the 59th minute came from Berg, exploiting the still too-large space ahead of Atlético’s midfield in the 4‑4‑2. Barrios and Koke were pulled out by Bodø’s half-space movements, allowing Berg to reach the box. Høgh finished after some chaos – a well-deserved goal. Bodø continued largely with counterattacks, while Atlético, despite entering the final third more frequently, struggled to find vertical paths against Bodø’s increasingly deep and compact 4‑4‑2/5‑3‑2. Instead, Atlético relied on wide crosses, which became problematic for Sorloth, who was nearly always doubled by the center-backs, while the No. 10s remained too central to pull Sorloth free or provide additional box options.

Conclusion

I had originally planned an analysis on Juventus on Twitter (to come!), but these inspiring Norwegians got in the way. While they faced more difficulties against Atlético than against City, they clearly demonstrated that they belong on the big stage and can compete. Underestimating them would be a mistake. The 4‑4‑2 mid-block system may reach its limits against even stronger teams – as Atlético occasionally showed, particularly when they faded in the second half.

MX made a name for himself in Regensburg with his penchant for over-visualizing the game. While he flirted with the RB school of thought, he secretly remained a romantic at heart for Guardiola’s football artistry.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen