Between a Lack of Stability and Connection Issues

Tottenham Hotspur and TSG Hoffenheim disappoint on Thursday evening in Sinsheim, with Hoffenheim showing promising adjustments in the second half but still falling short. It was a match defined by approaches and ambivalence, as both teams displayed glimpses of potential but lacked the necessary consistency and presence. (MX)

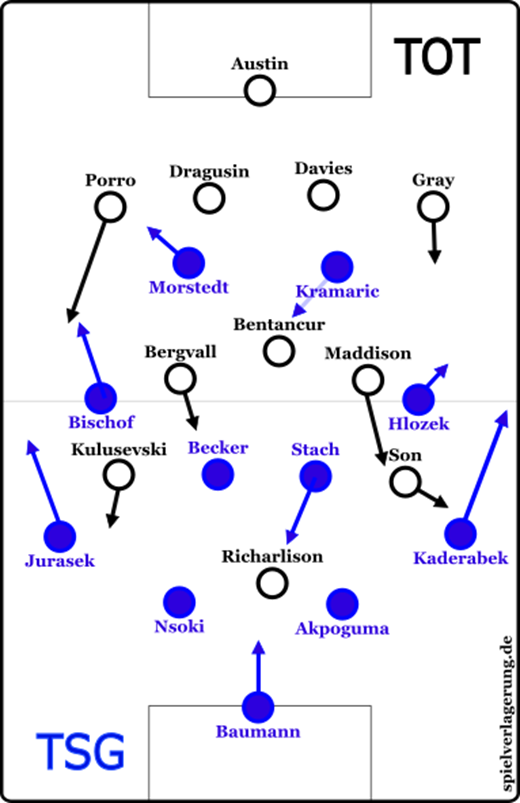

Christian Ilzer and TSG Hoffenheim were under pressure on the penultimate matchday of the UEFA Europa League: Only a win would keep their theoretical chance of direct progression alive. The Austrian coach opted for a 4-2-2-2 formation. Oliver Baumann performed as usual as the goalkeeper, with Akpoguma and Nsoki forming the center-back duo, flanked by Jurásek on the left and Kadeřábek on the right. The double pivot consisted of Stach and Becker, while Bischof – who will soon join FC Bayern – and Hložek were deployed in the half-spaces. Up front, Morstedt and Kramarić played as a dual-striker pair.

On the opposite side, there was also significant pressure on Ange Postecoglou and Tottenham. Domestically, the team was in a difficult situation, and in the Europa League, a win was necessary to keep their chances of progressing in their own hands for the following week. The Spurs lined up in a 4-3-3 formation, with Austin in goal. Dragusin and Davies formed the central defensive pairing, while Gray and Porro occupied the full-back roles. In midfield, Maddison, Bentancur, and the young Bergvall played as central figures. The attacking line consisted of Kulusevski, Richarlison, and Son.

Hoffenheim’s 4-4-2 Pressing System

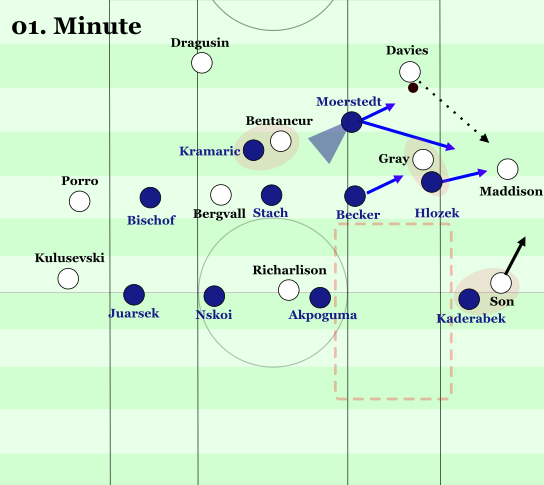

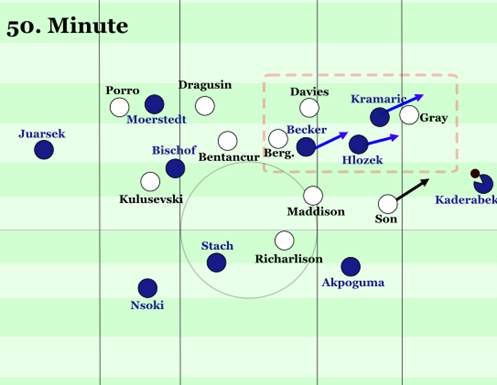

The Hoffenheim pressing structure without the ball was primarily based on a 4-4-2 formation, which Ilzer had successfully used in recent weeks and also in Graz for midfield pressing. In this formation, Bischof and Hložek played as wide players, while Moerstedt and Kramarić formed the first pressing line. The ball-near striker didn’t press the ball-carrying center-back directly, but rather in a looser manner. The main focus was on controlling the diagonal dribbles of Dragusin and Davies and blocking the diagonal passing lanes into the center. Additionally, the far-side striker often took on the task of marking Bentancur, the central defensive midfielder.

A key characteristic of Ilzer’s approach was also that the strikers often moved wide from their diagonal pressing movements, putting more pressure on the width and preventing backward passes more effectively. This approach indirectly highlighted how crucial compactness is for Ilzer’s system. Without tight distances between the lines, it was difficult for the strikers to press effectively and create double pressure. In situations where compactness was not ensured, such as in some midfield pressing moments, unfavorable 1v1 situations arose that significantly diminished the advantage of the system, as the player could directly engage in a 1v1 duel instead of a 1v2 situation with the pressing striker.

The attempt to block diagonal movements by the pressing striker inevitably led to a drawback: Tottenham was increasingly forced to play wide. Here, Hoffenheim showed some ambivalence. Tottenham frequently positioned their full-backs in half-space, forcing Bischof and Hložek to track them. The issue, however, was that the width, which should have been covered by the outer midfielders in the 4-4-2 system, was insufficiently secured. This created patterns that became an increasing challenge for Hoffenheim.

Tottenham’s Width-Based Strategy

Postecoglou likely recognized the importance of exploiting width in deeper spaces ahead of the match, aiming to establish patterns that would facilitate effective use of the width.

The half-space players in the 2-3-2-3 system, Bergvall and Maddison, made dynamic movements into the wider areas, made possible by Hoffenheim’s first pressing line. The goal was to create shorter connections for the center-backs to progress into the wide areas. Complementing this, the full-backs, Porro and Gray, deliberately positioned themselves to bind Hoffenheim’s wide players, Hložek and Becker, in the half-space, thereby providing more space and time for Tottenham’s wide players.

Hoffenheim responded solidly, especially through clear handovers. The central midfielder, in this case, Becker, would situationally take over the full-back, allowing the wide player to shift into the wide areas. However, Maddison could have made more of the side pressing angle from Hložek in some situations. By turning directly forward, he could have bypassed the pressure from the first line and, alongside Son, created a 2v1 against Kadeřábek. This option, however, was rarely utilized.

Son repeatedly dropped deeper, pulling Kadeřábek out of the defensive line, but this often led to a lack of consistent height occupation for Tottenham. As a result, many progression opportunities—especially down the left side—remained ineffective. Although Hoffenheim’s attempts to push the full-backs wide created space in the half-space, Porro did exploit these opportunities successfully in a few instances, but overall, he did so too rarely to create sustained attacking dynamics. Richarlison could also have moved into these spaces more frequently in the opening phase to strengthen the attacking rhythm.

In general, one positive aspect was the consistent use of layoff play on the right build-up side, with Porro tucking inside. Bergvall, who positioned himself wide, showed excellent awareness of the game situations under pressure from the opposition. He quickly recognized that Stach was marking Porro loosely, which allowed Bergvall to frequently find Porro in the center. This situation was well exploited, leading to effective one-two patterns and significantly supporting the build-up structure on the right side.

Tottenham’s Half-Space Positioning and Defensive Weaknesses

A recurring pattern for Tottenham was the positioning of the half-space players. They often remained in their usual positions, staying in the half-space rather than fully occupying the width, but frequently aligning with Bentancur, which resulted in a 2-5-3 system. This setup was often accompanied by deeper, but wide, movements from Kulusevski and Son.

Due to the binding of Hložek and Bischof by Tottenham’s half-space players, Hoffenheim found it difficult to transfer the ball into the wide areas in a ball-oriented manner. Instead, they were forced to play out through the full-backs, which revealed weaknesses in the ball-oriented shifting of their defensive line. This resulted in large gaps, which Tottenham sought to exploit through quick vertical movements, especially in the half-space. Bergvall in particular pushed forward several times, but tended to do so too quickly, making it difficult for Kulusevski to receive the ball in these patterns. Nsoki, however, defended man-to-man and was able to largely isolate Bergvall’s movements.

Overall, Kulusevski struggled, particularly under the pressure exerted by Kramarić’s pressing, which intensified the pressure. Return passes to the defensive line were consistently denied. Kulusevski had noticeable difficulty, especially with his first touch, to escape these tight situations.

An additional factor was that Kulusevski was often forced to turn using his weaker foot. Combined with the double pressure from Hoffenheim, this led to significant issues in ball control, making it difficult for him to find Bergvall diagonally in the half-space.

2-0 and 50% Possession at Halftime

By the end of the first half, Hoffenheim had only partially been able to capitalize on Tottenham’s initial struggles. What stood out most was that the characteristic pressing through the strikers became less frequent, as Bentancur shifted closer to the ball, increasingly binding the ball-near striker, which led to a noticeable decrease in the intensity of the overall pressing. This change allowed Tottenham to play more return passes and initiate new build-up attempts without being under constant pressure.

Additionally, Son was regularly placed in 1v1 situations in the final third towards the end of the half, which naturally created dynamics—helped by some unfortunate defensive actions from Kadeřábek. Furthermore, Richarlison and Maddison often found space in the in-between lines. The large gaps in Hoffenheim’s 4-4-2 system offered Tottenham the opportunity to target these players and create additional dynamics in their offensive play.

Despite the early lead and a 2-0 score before halftime, Tottenham had just over 50% possession against Hoffenheim by the end of the first half. This surprisingly low figure was partly due to the disjointed nature of the game: many ball losses and fouls characterized the match, with Hoffenheim particularly focusing on physical intensity in the half-space. Additionally, Tottenham showed general problems with coordination and connections between players. Notably, the lack of ball flow was apparent: passes often went astray, and there were difficulties with the first touch— a crucial disadvantage, especially for a style of play that heavily relies on width and time advantages along the sidelines.

Through the 2-5-3 (or 2-3-5 in the final third), Tottenham also revealed significant weaknesses in their counter-pressing. This was primarily due to ball losses occurring frequently in the wide areas, with surrounding players often moving away from the ball. As a result, there was a lack of necessary ball concentration near the ball, making an effective, pressing-oriented counter-pressing difficult to execute, forcing Tottenham to frequently fall back instead.

Hoffenheim targets Moerstedt

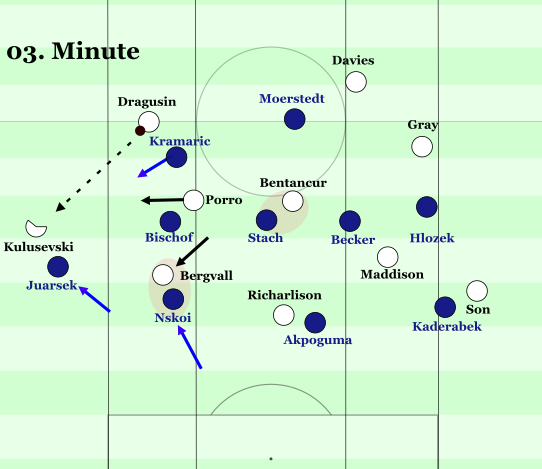

In Hoffenheim’s build-up play under Ilzer in the first half, a clear game plan was evident: instead of a short build-up, they focused almost entirely on long ball distribution.

In principle, the team played out of a 2-3-5 formation, with Kadeřábek and Jurasec positioned more centrally in the second build-up line, but occasionally shifting wide. Stach operated centrally between them, while Becker frequently advanced from the back line and occasionally dropped into the intermediate spaces.

The extreme overload of the back line was closely linked to Max Moerstedt, who acted as the target player. The striker regularly drifted to the left side, positioning himself close to Porro in order to receive long balls. Around him, three players—usually Bischof, Kramarić, and another teammate—positioned themselves to ensure that the area around the ball was well occupied.

The central issue with this approach, however, was the overly tight positioning of the players around Moerstedt. The second balls often ended up in more distant zones (green zone), areas that Tottenham could access well from their 4-4-2/5-3-2 structure. Notably, the wide players Son and Kulusevski frequently shifted excellently into these spaces, leading to dangerous counter-attacking situations.

Both goals conceded in the first half resulted from ball losses in these zones, which Hoffenheim failed to protect effectively. Tottenham’s quick transitions and precise vertical play made the problems with the long ball distribution clearly visible.

In general, Moerstedt had a rather unsuccessful day with the long balls. While the balls were often played back towards Baumann intentionally, these passes frequently lacked precision. Additionally, both Porro and Drăgușin were extremely dominant in aerial duels on this occasion.

Sending Moerstedt into an aerial duel within a densely populated zone also assumes that the team maintains a certain depth behind the target player. However, Hoffenheim failed to establish this depth adequately, resulting in second balls rarely being secured in the deeper areas.

Towards the end of the half, Hoffenheim shifted its strategic focus from long balls to short build-up plays, which were mainly initiated on the right side. Kadeřábek positioned himself increasingly wide, which proved effective, as his direct opponent Son, starting from a half-space position, had to cover a long pressing distance and often arrived too late. This allowed Kadeřábek to receive the ball.

From there, Hoffenheim attempted to play quickly into depth to Hložek or Becker. However, Tottenham effectively defended this option through consistent man-marking. Becker’s dropping movements were frequently neutralized by Maddison’s covering shadow in the half-space, while Stach was largely covered by Richarlison, limiting the connections into the center significantly.

Adjustments in the Second Half

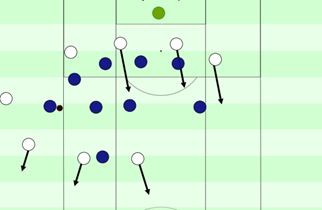

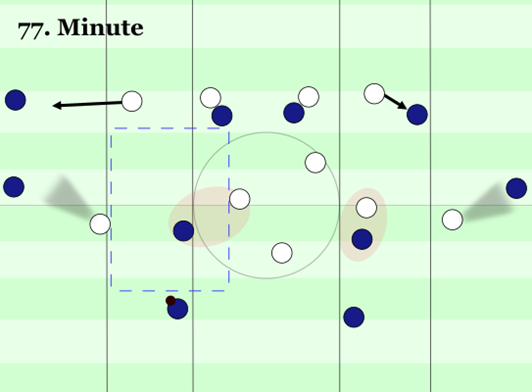

In the second half, Hoffenheim continued with this approach, but increasingly operated from a 2-3-4-1 formation, while Tottenham defended in a 4-1-4-1. The full-backs positioned themselves in extreme width early in the build-up phases to maximize the pressing distances of their direct opponents. This approach remained effective: With clean first touches, Hoffenheim occasionally managed to beat their opponents with dribbles.

The biggest difference from the first half lay in the subsequent movements from wide positions. Unlike in the first half, Hoffenheim refrained from structurally overloading the last line. The focus shifted towards deeper positioning to create diagonal passing options. This allowed Hoffenheim to either play directly behind Tottenham’s defensive line or use the space in between, where Hložek was frequently available for a pass.

Closing Stages

There were also frequent rotations, for example between Bischof and Becker, which created additional dynamism. Kramaric often dropped into the defensive midfield space, allowing for the resolution of the isolation of that space by Richarlison, as Tottenham didn’t follow these wide runs in their man-marking system. This allowed Kramaric to distribute the ball on several occasions.

A positive aspect was that Akpoguma kept up with Kadeřábek’s wide movements, constantly offering a return pass option. Meanwhile, Stach often dropped deeper to cover space for counter-attacks—a lesson learned from the first half. Since Tottenham struggled to defend the width consistently, the pressing became deeper, and Hoffenheim’s pressure steadily increased.

Although Hoffenheim almost completely stopped playing long balls, the wide fullbacks presented themselves as viable options for diagonal switches, which were frequently sought. Sometimes Bischof also dropped wide to be available for these passes. These passes were mostly successful, as they were played into open spaces rather than into congested areas. Moreover, the 2-3-4-1 formation allowed for much better access to second balls due to the increased midfield presence.

For Tottenham, however, it remained a similar game to the first half. They still faced significant problems with the opponent behind them and technical difficulties in their ball retention play. Solanke added a bit more depth in the forward position, while Moore displayed more dribbling strength on the left wing. Despite some good individual actions, the problem areas—particularly in the final third from the very static 2-3-5—were still largely unresolved. Hoffenheim, on the other hand, simply had a better ball possession structure and dominated the game with nearly 61% possession. The counter-pressing issues ultimately led to Hoffenheim’s 1-2 goal.

Towards the end of the match, Ilzer switched to a 2-4-4 system with double-wide wingers, while Spurs also switched to a 4-1-4-1 formation, defending much wider. They tried to directly cut off the connection to the wide fullbacks, which they succeeded in doing effectively. Once they were bypassed, however, the fullbacks advanced well. The central players were now more tightly marked, following movements towards the ball. It wasn’t until Moore failed to notice Kadeřábek’s off-the-ball runs in the 88th minute that Hoffenheim managed to break free on the wing and score the 2-3 goal.

Overall, Tottenham’s initially wider setup made the half-space more accessible, which Hoffenheim repeatedly attempted to exploit. However, Moerstedt and Kramaric found few solutions against Tottenham’s well-defending center-backs. Several of these situations led to relieving counter-attacks for Tottenham, which were also the most dangerous for them in the second half. Especially towards the end of the match, as Solanke and Lankshear pressed for ball recoveries, Tottenham could quickly play vertically forward after regaining possession. Maddison’s dribbling pace was also frequently on display in these moments. It was clear that the fact Tottenham was ahead and Hoffenheim needed to win played into their hands.

Conclusion

The conclusion is ambivalent. Both teams are going through a difficult phase, which was reflected in the match—many fouls, turnovers, and long balls shaped the game. It was not a particularly convincing display from two teams that, in terms of personnel and concept, should be doing better. Both sides were often forced into wide areas or specific zones, which fragmented the combination play in the final third and lacked the necessary dynamism.

However, there were still glimpses of solid, familiar approaches, particularly from Hoffenheim, though the team still lacks the presence and stability required to compete against stronger opponents. As Ilzer highlighted in the post-match press conference: “We’ve learned that we need to be more stable to get the right results. In duels man against man, we lacked something. Still, you can see we can play really good football. We ruin a good game for ourselves when we make such simple mistakes. It was too easy for the opponent.”

Postecoglou’s team also showed deficiencies, especially in ball movement, presence in the final third, and intensity without the ball. Ultimately, the team that managed to relieve pressure better came out on top, while the other, had they played the second half like the first, might have seen a different outcome.

MX flirted with the RB school but secretly remained a romantic when it came to Guardiola’s football artistry. He is currently working as an analyst at a youth academy and is also an author for ‘spielverlagerung next generation.’

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen