Overloads in Possession – MH

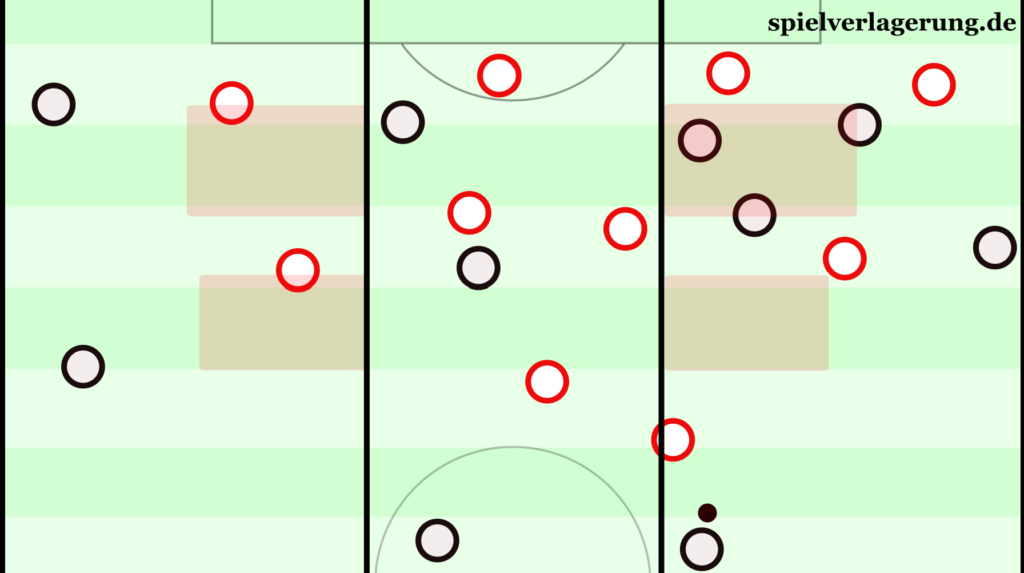

A key tactical tool in modern football is the use of overloads. Creating a (situational) numerical advantage allows for more effective combinations, opening up spaces, and disrupting the opponent’s defensive structure. This article explains the strategic benefits of overloads in various areas of the pitch and demonstrates how they can be created and exploited to pose challenges for the opposition.

Overloads refer to a tactical approach where a team deliberately creates a numerical advantage in a specific area of the pitch. This involves abandoning fixed player positions and instead shifting the focus to certain spaces.

In these areas, the reduced distances between players and the numerical advantage enable quicker and more effective combinations. In possession, overloads also create defensive problems for the opposition: against a zonal defensive approach, it becomes easier to exploit gaps between the lines, while against a man-oriented defense, opponents can be pinned down, creating space elsewhere on the pitch.

Certain factors influence the type and effectiveness of overloads. The opponent’s pressing style can determine the most suitable type of overload to exploit. Similarly, the game situation or scoreline may shape the objectives and, consequently, the most effective overload to use. Overloads can also highlight the qualities and strengths of specific player types in certain areas, making some overloads more effective or less so. Furthermore, the playing style of the team may naturally align with overloads in particular zones of the pitch.

Overloads can be used to achieve different objectives depending on the area of the pitch. It is particularly interesting to examine the potential goals, advantages, and applications of overloads in specific zones, taking into account the aforementioned factors. In this analysis, we will differentiate between the following areas of the pitch and opposition lines: the first line of the opponent’s press/own buildup zone, the opponent’s last line/defensive line, the central zone, the wings, the half-spaces, and the space between the lines.

Overload of the Opponent’s First Pressing Line / Own Build-up Zone

Functionality

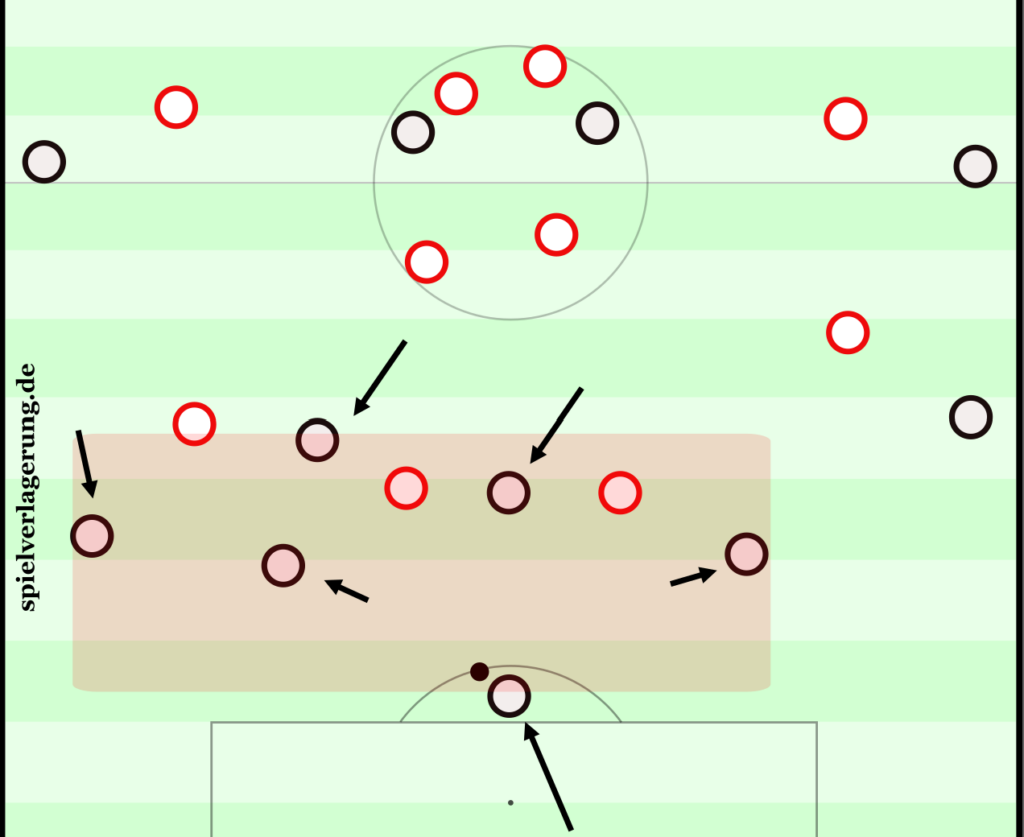

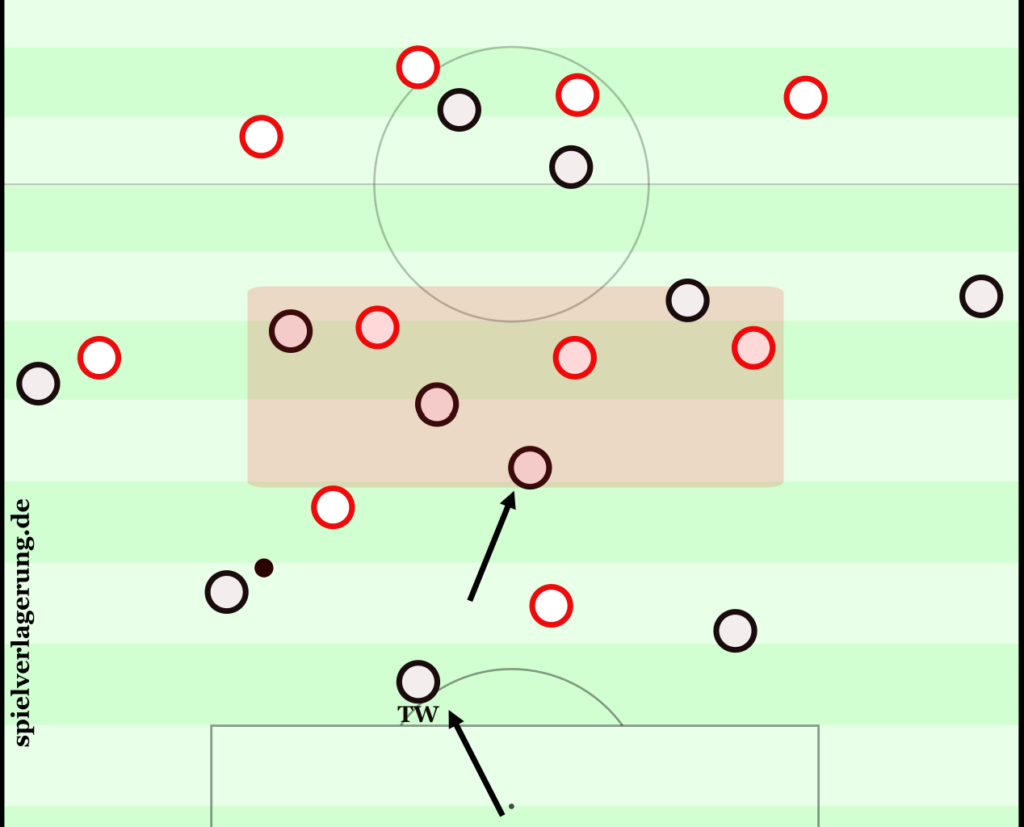

Overloads against the opponent’s first pressing line are used to minimize the risk of losing possession during build-up play. These overloads can occur before, on, or just behind the opponent’s pressing line. Therefore, it could also be referred to as an overload of the own build-up zone. The numerical advantage “ahead of the ball” makes the opponent’s pressing ineffective, preventing counter-attacks and generating more possession for the team.

Additionally, the opponent struggles to apply pressure on the ball carrier due to the numerical disadvantage in the press. The extra time and space created allow for a more precise and thoughtful build-up play.

The Opponent’s Dilemma

The opponent is faced with the following dilemma. Since no pressure is applied to the ball carrier, the team in possession maintains control of the ball. To continue creating transition moments through ball recoveries, the opponent must reinforce the first pressing line with more players. However, this results in spaces opening up, particularly in the midfield and sometimes in the defense. These gaps can be exploited by making runs into these areas, forcing the opponent into conceding goal-scoring opportunities after bypassing the first pressing line.

The principle of “lure and shock” is particularly evident here, as it is constantly provoked by the overload in the first build-up line. As the opponent seeks to apply pressure, they are forced to leave their original formation and engage in high pressing. This transition, due to the changing structure of the opponent’s formation, creates a prime opportunity for quick and direct play, exploiting the now vulnerable opponent through counter movements.

This brief phase of the game, in which the opposing team transitions from a deeper formation to a higher press, is not typically found in most tactical theories. In the widely used four phase model of a football match by Louis van Gaal, this phase would be classified under “own ball possession.” However, it is actually a combination of offensive transition from own possession, triggered by the opponent’s shift into a different defensive shape. Of course, the 4-phase model still offers advantages in terms of categorization and understanding the game.

Impact of Opponent’s Pressing Variations

Overloading the first build-up line is particularly effective against opponents who employ high pressing or midfield pressing. In high pressing, the opponent aims to win the ball as high up the pitch as possible, to reduce the distance to goal during offensive transitions. However, the overload in the build-up phase significantly complicates the opponent’s ability to win the ball.

Additionally, the opponent is forced to place more players in advanced areas, opening up the spaces behind their defensive line. Another advantage of the numerical superiority ahead of the ball against high pressing is the ability to protect your own goal in case of a ball loss during counter-pressing. More players ahead of the ball means more players are available to immediately defend in case of a turnover.

In midfield pressing, the opponent tries to keep the pitch compact while simultaneously applying pressure on the ball carrier. This approach minimizes the distance to the opponent’s goal, making offensive transitions very appealing when coming out of a midfield press. However, a downside is the often large space behind the defense.

This is where the advantages of overloads against the first pressing line come into play. On one hand, opponent’s offensive transition moments are prevented, thus stopping them from creating goal-scoring opportunities. On the other hand, the opponent is forced to press with more players. The “lure and shock” principle comes into effect, as the large spaces behind the defense in a midfield press can be exploited. If the defensive line drops back and covers the spaces behind, large gaps open up in midfield between the lines, which can be exploited.

An exception in midfield pressing occurs when the opponent does not want to apply pressure on the ball-carrying build-up player. In this case, additional players in the build-up line would be “wasted.” Here, the overload of the last line, which will be discussed later in the article, is particularly effective.

Similar problems arise when the opponent defends space-oriented without applying pressure. Particularly in defensive pressing or when sitting deep, the opponent often does little to actively win the ball back. As a result, when the own build-up line is overloaded, offensive passing options are limited.

The opponent exerting no pressure is especially common when the opponent has a narrow lead towards the end of the game. Naturally, this can be countered with overloads in other areas of the pitch. On the other hand, a 1-0 lead in the final minutes can also be “defended” through ball possession. In this case, it is particularly useful to overload the build-up line. Thus, the match situation or the score is often decisive for the effectiveness of the overload.

It would seem obvious that overloads in the own build-up line during goal kicks and when the opponent is closing down would be a suitable option, as the opponent wants to apply pressure and can thus be lured in. However, most teams fail to escape such situations without losing possession. This is partly because the ball is stationary, allowing the opponent to easily organize and apply maximum pressure. Additionally, the pitch is restricted at the back by the goal line during a goal kick.

Therefore, the team taking the goal kick cannot relieve the pressure by playing backward. Moreover, the ball is close to their own goal during a goal kick, making the risk of losing possession extremely high, and teams rarely attempt to hold the ball in these areas for long. Thus, overloads in the own build-up line are less effective due to the challenging conditions of a goal kick while the opposing team is closing down. This issue needs to be solved in the coming years and warrants an article of its own.

Player Profiles

The players who can benefit most from an overload in the own build-up line are those with strong ball-playing abilities who prefer to have the game in front of them. Real Madrid’s style of play, for instance, was tailored to Toni Kroos, who frequently dropped into the half-left position. His strengths in build-up play relieve and support the center-backs.

However, simply dropping a defensive midfielder into the build-up line doesn’t fulfill all the criteria of an overload. When the defensive midfielder drops into the back four, a 3v2 numerical advantage is created in the build-up line against an opposing press with two strikers. However, from the pressing team’s perspective, this creates a 2v3 situation. In this scenario, the pressing team can apply significant pressure on the opponent’s build-up players by using cover shadows. The main advantages of the dropping defensive midfielder lie in the connection play: opening new passing lanes, changing passing angles, and occupying new spaces that force the opponent to react in their pressing.

If we define an overload by its functionality, the mere dropping of a defensive midfielder does not qualify as an overload on its own. However, it can be part of an overload process, for example, in combination with a goalkeeper who joins the build-up and flat full-backs.

Moreover, particularly fast wingers or forwards benefit from an overload in the own build-up zone, as they can take advantage of the luring effect on the opponent and thus start exploiting spaces behind the opponent more easily.

Summary

Overloads in the own build-up line and build-up zone can provide greater game control through possession. They are particularly effective against opponents who aim to press build-up players. The opponent is placed in a dilemma between applying pressure and covering the spaces behind the pressing lines. Problems arise, for example, against deep-lying opponents, as a numerical disadvantage occurs near the goal.

Overload of the Opponent’s Last Line / Defensive Line

Functionality

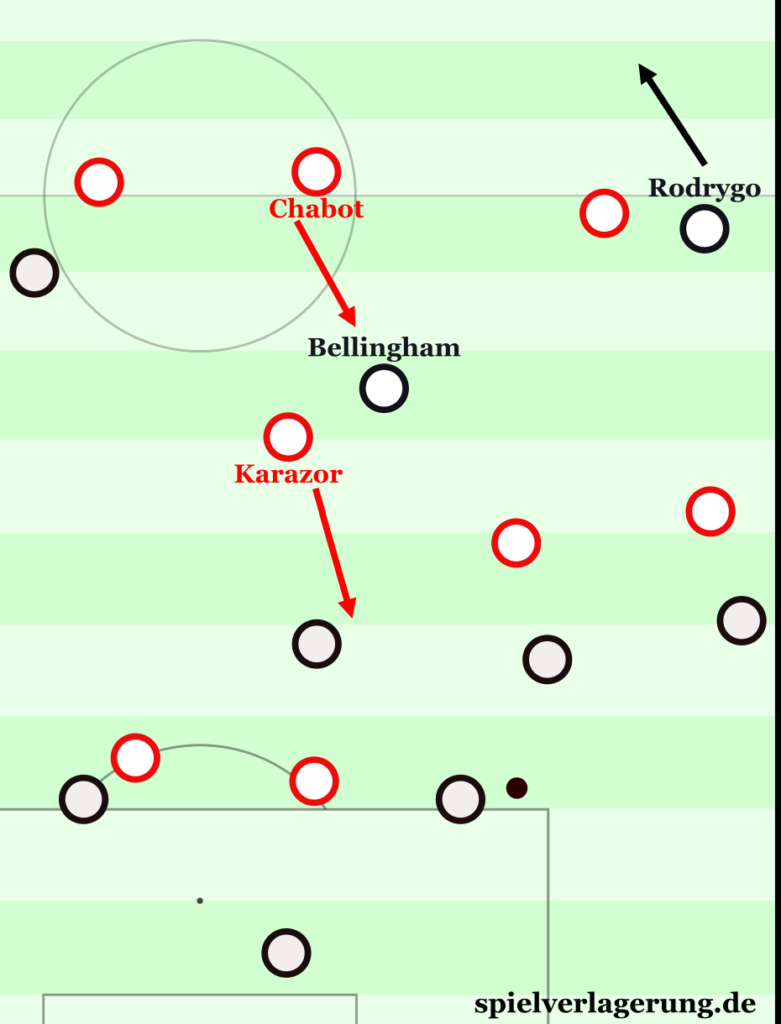

Overloads on the opponent’s defensive line force the opposing defense to become more engaged. This creates 1v1 situations with limited cover. As a result, the center-backs are put under more pressure and forced into more decisions, which can lead to costly mistakes.

To exploit these overload situations on the opponent’s last line, the own play becomes more vertical. The risky passes into depth required for this also lead to more ball losses, increasing the rate of possession turnovers. Consequently, this provokes more counter-pressing situations.

The Opponent’s Dilemma

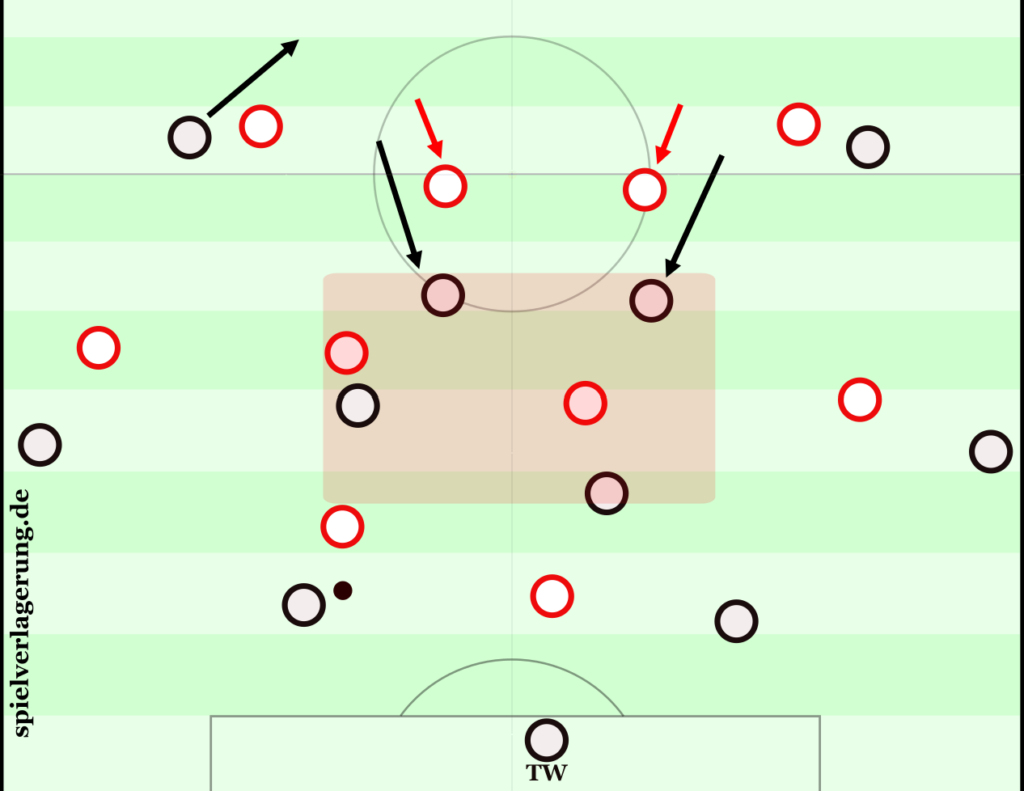

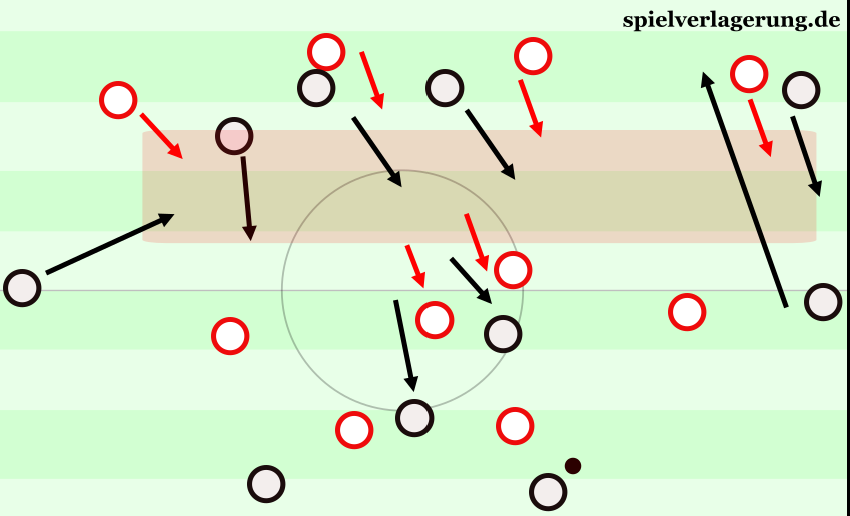

Overloads create more depth and penetration, as the attacking players can make numerous runs in behind the defense. Especially with opposite movements, the defense is forced to choose between risky 1v1 situations and leaving the attacking players unpressured as they come towards the ball.

Due to the problems created for the defense, high pressing teams with a high defensive line can be effectively exploited. If the pressing team fails to apply enough pressure on the ball, they can be bypassed with a few deep passes into the overloaded zone.

Furthermore, multiple runs into depth force the opposing defensive line to constantly drop back for cover. This leads to a loss of height, increasing the space between the defensive line and the midfield, and causing the pressing team’s compactness to break down. The opponent can be more easily bypassed due to the expanded space and time. To maintain compactness, the opponent would have to drop back collectively, which would push them towards their own goal.

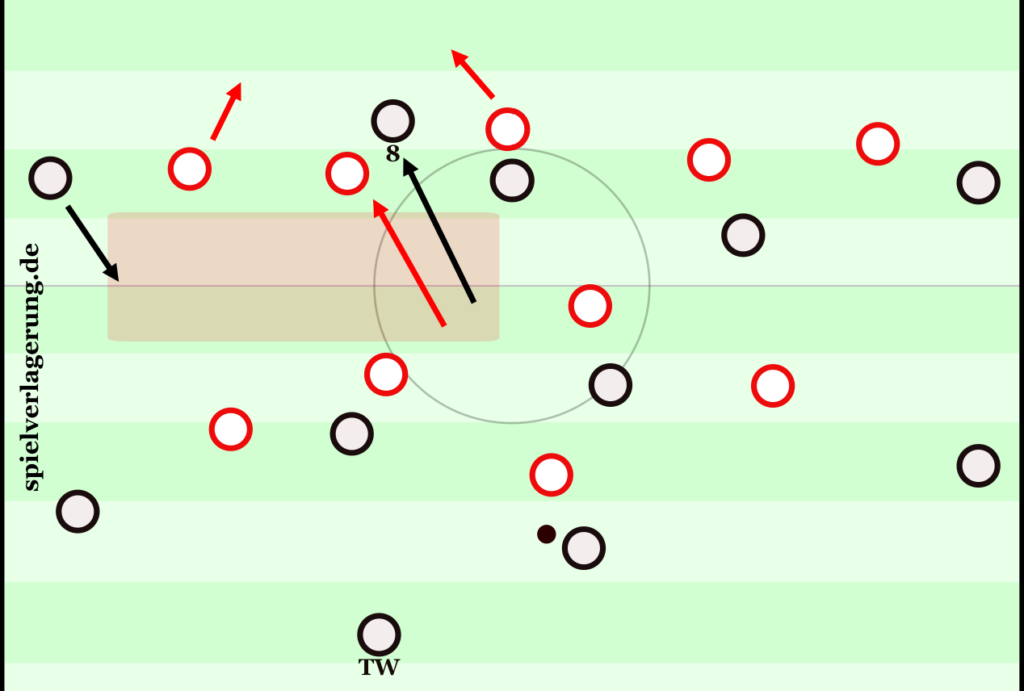

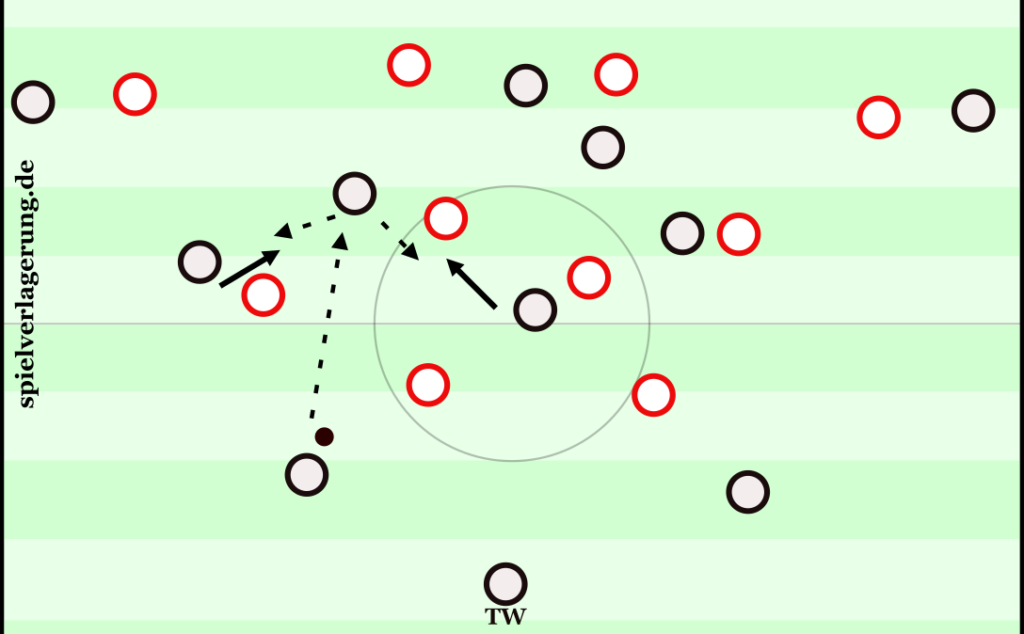

The run of the number eight (central midfielder) into the depth, towards the last defensive line, further overloads the opponent’s defensive line. The surrounding defenders are forced to provide cover and drop back. Through opposite movements from the striker and the winger, the now larger space between the defensive and midfield lines can be exploited.

A possible solution to this problem lies in the offside trap currently employed by Barcelona. This tactic helps prevent runs into depth while still applying pressure, maintaining compactness. To minimize the admittedly high risk of this approach, it could be applied more situationally in the future. This would make it more difficult for the opponent to anticipate and counter it effectively.

Impact of Opponent’s Pressing Variations

Against the opponent’s attacking press, overloads on the last defensive line are used to create as much playable space as possible. Since attacking pressing takes place in the opponent’s half and the halfway line marks the offside line, the opponent’s defensive line can be pushed up to the halfway line. This disrupts their compactness.

Even against the opponent’s midfield press, an overload on the last defensive line can be very effective. The weakness in the midfield press lies in the space behind the high defensive line. The 1v1 situations created by the overload on the last line can be continuously provoked with deep passes.

By binding the last defensive line, defenders can be repeatedly pulled out of position, creating space behind the defense. The defenders’ focus is on the 1v1 duels. Through deep runs from the deeper-lying midfielders or full-backs into the spaces behind the last line, the defensive line can be bypassed. If the opposing defender does not step out, the attacker can be played into the space between the lines. This creates a handover problem between the defender and the midfielder.

The counter-pressing, repeatedly provoked by deep passes, can also become a key factor. In counter-pressing situations, the opponent is in an offensive transition phase and, if successful, is often poorly organized defensively. Therefore, regaining possession after a counter-press is particularly dangerous offensively. Strong counter-pressing teams, such as Liverpool, often overload the opponent’s last defensive line and play vertically to provoke as many counter-pressing situations as possible, in which they are superior to the opponent.

Against the opponent’s defensive pressing or when the opponent is “parking the bus,” overloads on the last line are much less effective. Due to the opponent’s compactness and the deep defensive line, the necessary spaces to release attackers become harder to find. Playing into the space behind the defense is nearly impossible. A more effective strategy is to position players just a few meters ahead of the defensive line. We will discuss this overload in the section on the spaces between the lines.

While the provoked counter-pressing can lead to scoring opportunities, it is much less effective due to the large number of players positioned ahead of the ball. Other areas of overload are more suitable in this case. By positioning the overloaded players a few meters ahead of the defensive line, it becomes possible to effectively exploit a deep-lying block. We will address this in the context of overloads in the spaces between the lines.

Player Profiles

Especially on the last line, fast and strong 1v1 players are essential due to the required runs into depth. This forces the often slower center-backs to cover deeper and earlier, disrupting their defensive compactness. Additionally, having an athletically strong target player on the last line, who can hold the ball with his back to the opponent, can be useful. Despite this, his speed allows him to make runs into depth. This way, the ball can more frequently be played into the overload situation, and opposite movements become harder to defend.

Due to the overload on the last line, the own build-up players can come under pressure more quickly. This means that especially ball-playing center-backs are needed, players who can break the lines with passes even under pressure to release attackers. They can be relieved in build-up play by technically strong full-backs tucking inside. At the same time, the speed of the full-backs can be a key asset in this style of play. They can make runs into depth and attack the space behind the defense.

When it comes to the full-backs, it’s important to consider their individual strengths and use them accordingly. For example, Bayern Munich’s fast Alphonso Davies frequently makes runs into depth, while Guerreiro, a technically gifted full-back, primarily supports the center-backs in the half-space.

A key element of this vertical style of play is a strong midfield for counter-pressing. “Strong” in counter-pressing doesn’t only mean tackling ability. Acceleration, decision-making speed, football intelligence, and good spatial awareness are also valuable attributes. One player who currently excels in this aspect is Rodri from Manchester City.

Summary

An overload on the last line creates a vertical style of play and is particularly suited for teams strong in counter-pressing. Through numerous deep runs, the opponent’s compactness can be disrupted, especially when their defensive line is high. Challenges arise in the defensive requirements during build-up play, as well as for the defensive midfielders (6s) in counter-pressing situations.

Overload of the Center

Functionality

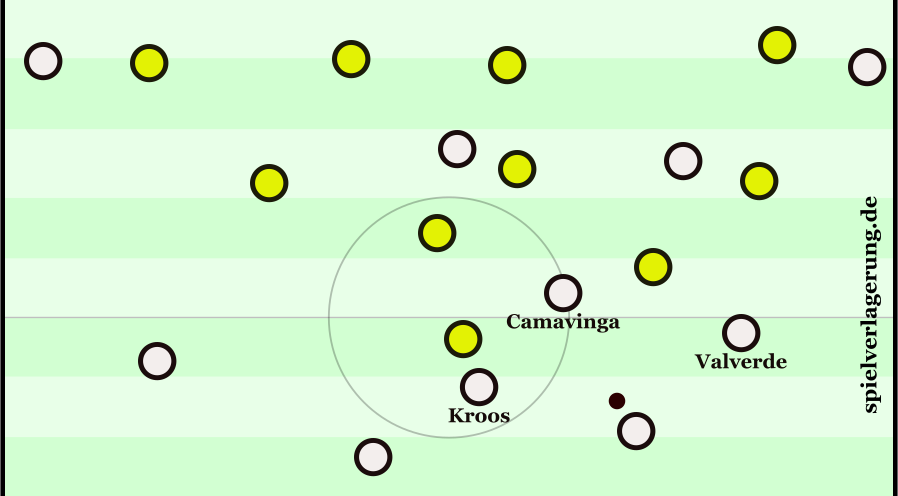

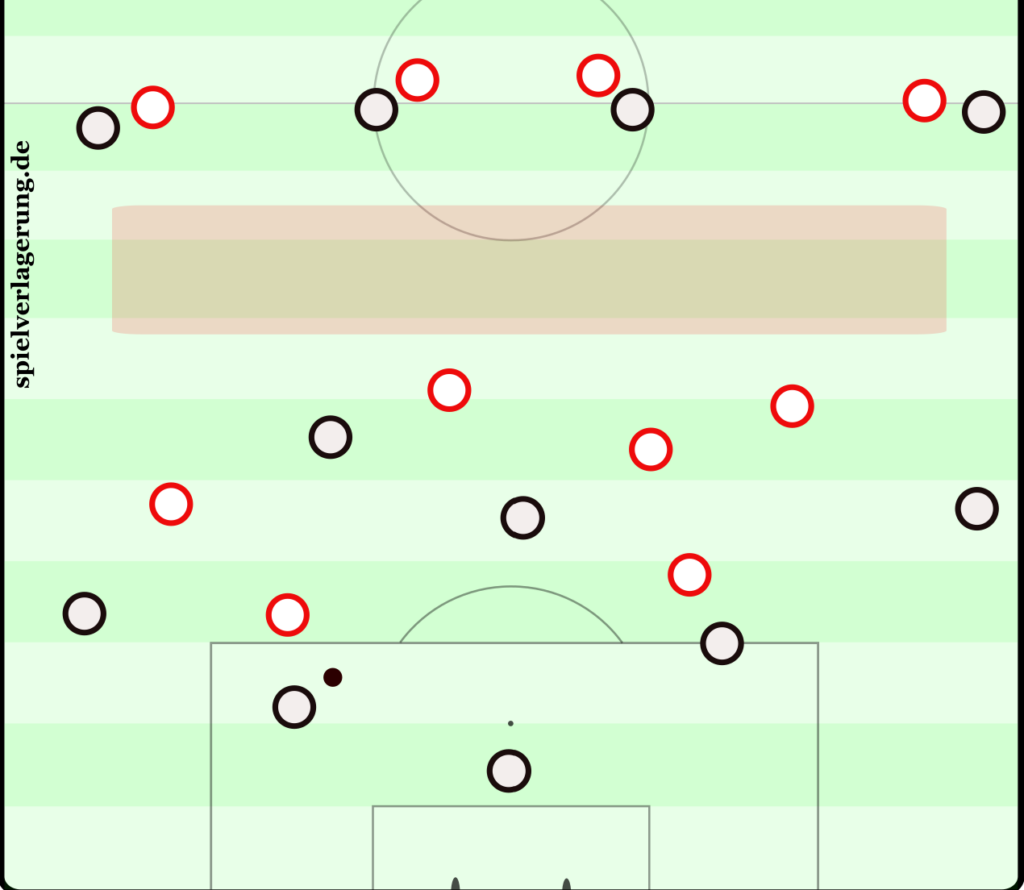

The center is considered the most strategically important area of the field. It connects all areas of the pitch, allowing players to attack any part of the field more flexibly and quickly. Offensively, the center provides the shortest route to goal and contains the most dangerous areas. Defensively, protecting the goal-scoring spaces in the center is crucial. In transition moments, the center determines the direction of play. Therefore, the tempo and rhythm of the game are set in the center.

Overloading the center provides a significant advantage in transition play. Counter-pressing becomes much more effective due to the high number of players in the center. The routes to the ball are shorter from the center, allowing a numerical advantage to be quickly created near the ball in case of a loss. Additionally, the opponent cannot shift the ball through the center into the open, far side spaces. When regaining possession, the opponent’s goal can be attacked more quickly from the center.

This is also one of the reasons why Manchester City has an exceptional record in winning counter-pressing situations. Liverpool, traditionally associated with counter-pressing, has a less successful rate due to their overloads in the forward zones and more vertical play, but they create quantitatively more (successful) counter-pressing situations.

It makes sense to overload the center to control the game. Pep Guardiola, in particular, aims to dominate every game through possession and frequently overloads the center. This can be done by various players.

A commonly used tactic is the inverting full-backs from a back four. Since only two width providers are needed in possession to stretch the field and open up passing lanes in the center, the full-backs can overload the center by tucking into the half-spaces. When the winger comes inside, it creates a dilemma for the opponent’s full-back. They either have to cover the inverted full-back with a cover shadow or close off the passing lane to the usually strong 1v1 winger.

Another option is the advance of the central center-back from a back three. When the opponent presses with at least two forwards, a three-man build-up can still be created with the goalkeeper’s chain. Fabian Hürzeler frequently pushed his central center-back forward in build-up play at St. Pauli. Similarly, Guardiola often pushes players like Akanji into the midfield.

The “false nine” is another way to overload the center. Here, the nominal striker repeatedly drops into the center, creating confusion in the opposition’s defensive structure. Kai Havertz, for example, plays this role at both Arsenal and for Germany.

Even with two forwards, these movements can be used strategically to put the opposing center-backs in a dilemma. If the center-backs don’t step up, the two forwards can easily receive the ball in the spaces between them, bypassing the opponent’s press. On the other hand, if the center-backs apply pressure on the dropping forwards, a space opens up in the center of the last line, which can be exploited by fast wingers, full-backs, or central midfielders making runs.

The Opponent’s Dilemma

In addition to the dilemmas faced by individual opposing players, an overload of the center usually forces a central focus from the opponent due to its strategic importance. This often leads to 1v1 situations on the wings with plenty of space. By overloading the center, 1v1 situations on the flanks can be intentionally created, allowing the 1v1 strengths of the wide players to be better utilized.

Impact of Opponent’s Pressing Variations

Overloads in the center are always valuable, regardless of the opponent’s defensive schemes, due to the strategic importance of the central area. Nevertheless, the positioning of the players involved in the overload will be influenced by the opponent’s pressing.

Against opponent’s high pressing, the focus of the pressing team is on the front pressing line. The aim is to apply as much pressure as possible on the build-up players to provoke turnovers close to the goal. Therefore, it is crucial to create overloads in the center closer to the own build-up line, in the gaps of the first opponent’s pressing line. This way, the first pressing line can be played around more easily with diagonal, flat passes through the gaps, disrupting the focus of the opponent’s front pressing zones.

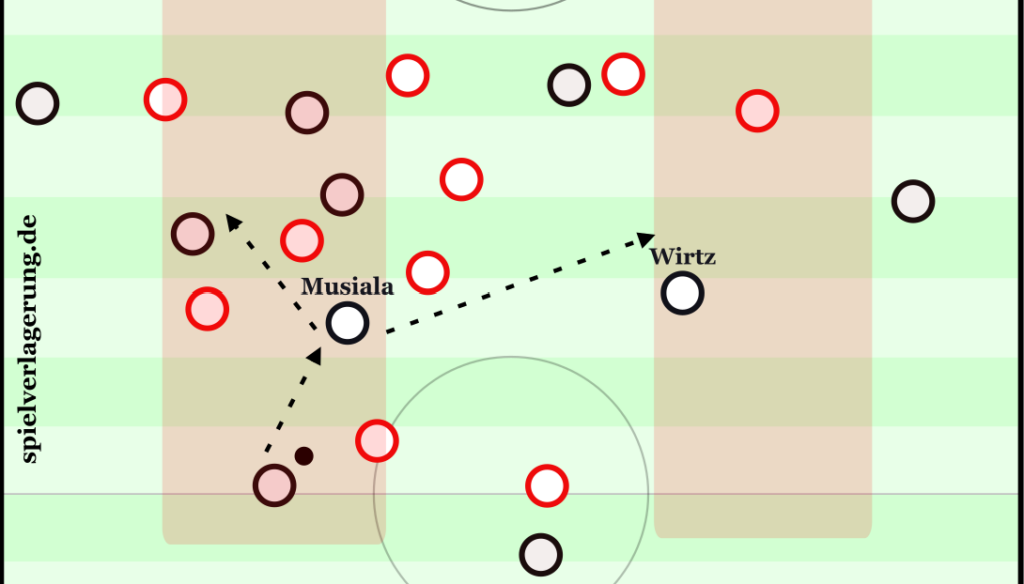

Another example of this is the deep-dropping number 10, like Musiala at Bayern Munich. The advantage of a dropping number 10 lies in the player’s individual strengths. Musiala, who excels in tight 1v1 situations, is not only particularly press-resistant but can also create further overloads by winning 1v1 duels. Therefore, it is advisable to position players with similar abilities in the spaces behind the opponent’s first pressing line when facing opposition high pressing.

In the case of the opponent’s midfield or defensive pressing, the center is particularly compacted. Thus, a center overload should be structured at different depths to create easier passing options. A staggered positioning better opens the spaces between the lines, establishes diagonal connections, and facilitates lay-off passes. This is why Guardiola never positions his two defensive midfielders horizontally on the same line in build-up play.

Additionally, a vertical staggered positioning in the overloaded center facilitates the transition into counter-pressing, as defensive cover is immediately available.

Player Profiles

The reason why full-backs typically overload the center while wingers act as width providers lies in the different strengths of players in these positions. The 1v1 situations created on the flanks are particularly useful for players who are strong in offensive 1v1 duels and have good pace.

An example of this is Vinicius Junior. By binding the opponent in the center, Vinicius’ strengths can be better integrated into the team’s play. This allows him to engage in 1v1 situations more frequently. Full-backs, on the other hand, tend to think more defensively and are therefore often stronger in counter-pressing situations. By moving into the center, full-backs make the counter-pressing more effective.

Summary

The center is the most strategically important area of the pitch. Overloading the center also leads to more effective counter-pressing. This overload can be achieved through inward-moving full-backs, advancing center-backs, or dropping strikers. By overloading the center, space is created on the flanks, allowing for the provocation of 1v1 situations. As a result, players like Vinicius Junior, who are strong in offensive 1v1 duels on the wing, particularly benefit from this approach.

Overload of the Half-Spaces

Functionality

To explain the functionality of overloads in the half-space, we first need to look at the half-space zone itself. The half-space is located between the wing and the center when dividing the pitch vertically. As such, it acts as a connection zone. Due to its proximity to both the wing and the center, it can be overloaded more quickly and easily than other zones. Faster overloads mean a shorter reaction time for the opponent.

Additionally, the half-space plays a strategically important role offensively. Unlike the wing, players in the half-space have full freedom of decision-making, as the touchline does not limit the space here. Because of its proximity to the goal, the center is best protected defensively, while the half-space usually faces less defensive pressure than the center.

Moreover, the half-space allows for easier creation of dangerous diagonal plays. Diagonal passes from the center inevitably move away from the goal, while diagonal passes from the wing are more challenging to execute due to the touchline’s strategic limitations. In the half-space, these disadvantages are neutralized.

Another aspect is the unfamiliarity of the half-space for defenders. Defenders are used to playing either on the wing or in central defense. The half-space, however, is a transitional zone that doesn’t fully belong to either of these areas, leading to marking problems. Additionally, the passing angles and options change compared to more familiar positions, requiring a different defensive approach.

A detailed article on the strategic advantages of the half-spaces is linked here.

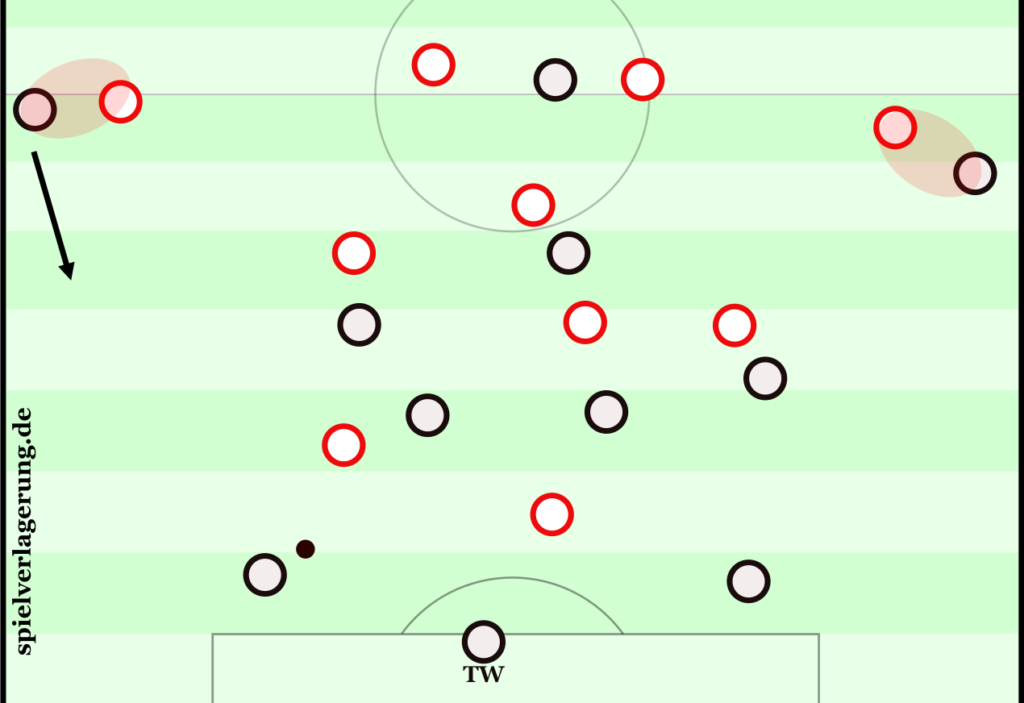

The half-spaces are therefore a crucial zone for generating goal-scoring opportunities against compact defenses. Overloading the half-spaces creates numerical superiority and thus control over these key areas. Overloads can be seen as a multiplier of these advantages. The difficult-to-grasp asymmetry of overloads generally creates the necessary chaos in an otherwise compact and well-organized defense.

The Opponent’s Dilemma

By overloading the half-space, various dilemmas can be created. Fundamentally, this holds the key to breaking down compact defenses. The flexibility of overloading the half-space with different players generates diverse dilemmas, pulls defenders out of position, and increases the likelihood of a successful attack.

The advancing full-back can tuck in either centrally or into the half-space. The benefits are similar: freeing up the passing lane to the wide area and/or creating numerical superiority in a central zone. However, if the full-back’s primary goal is not to draw their opponent out, but rather to create a passing option that overcomes pressing, it is more advantageous for the full-back to orient towards the half-space.

There is less defensive pressure here, making it easier for the full-back to be found. Additionally, the shorter run allows the full-back to exploit the space before their opponent can react. To create an effective dilemma, teammates in the half-space should move vertically in the opposite direction to the advancing full-back.

The inward-moving winger creates a similar dilemma when entering the half-space. The opposing team faces the choice of either allowing an overload in the half-space or leaving the flank exposed. The flank can, for example, be exploited by an advancing full-back. Additionally, the asymmetry created by leaving the wing unoccupied is harder to defend. The defender must move into unfamiliar spaces and react spontaneously, as the situation is unfamiliar to him.

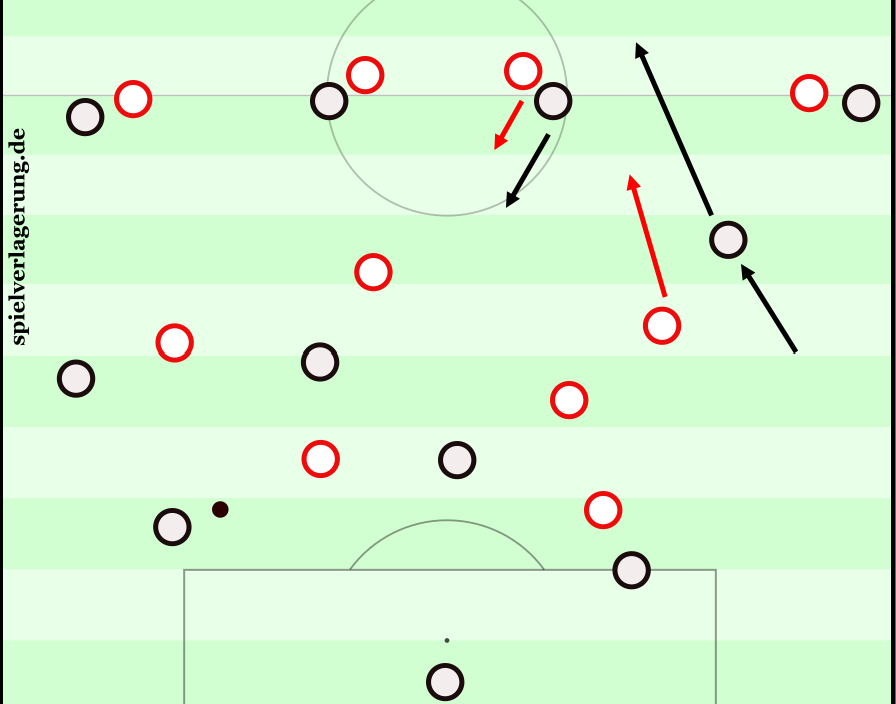

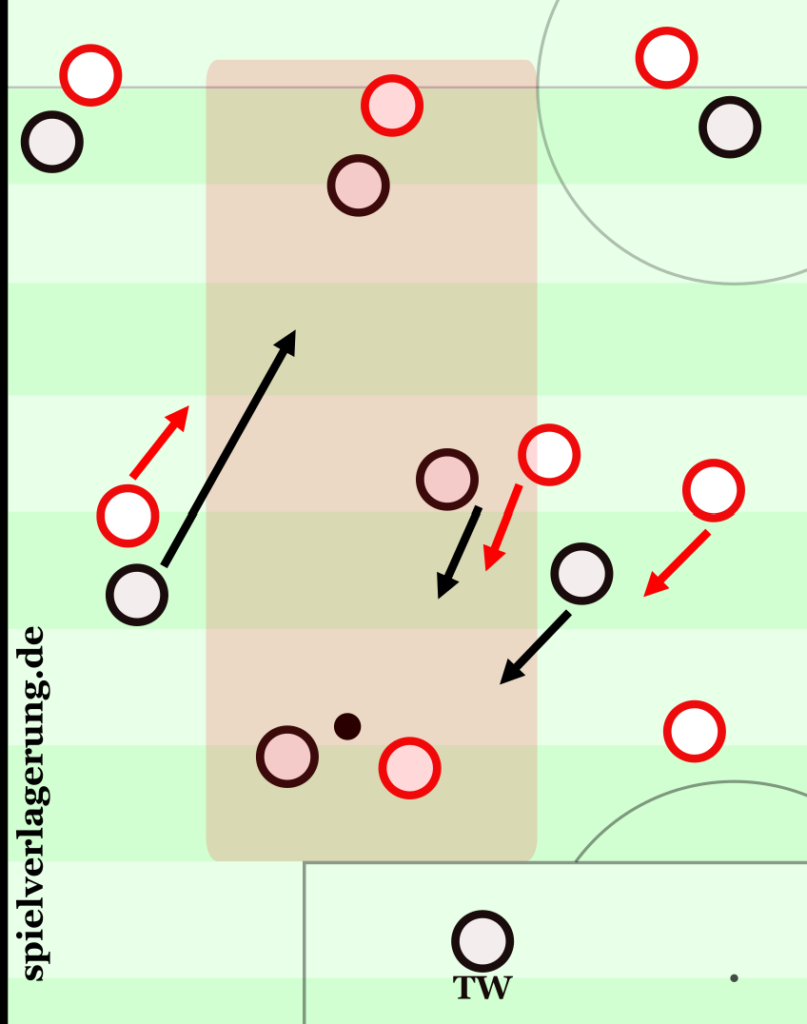

Another option is the inward movement of a ball-far player into the ball-near half-space. In a 4-4-2 formation, this could be the far-side striker, while in a 4-2-3-1, it could be the far-wing player. This movement typically creates an overload in the half-space, as most defenders are tied to defending a specific area. Especially players from the opposing defense line find themselves in a particularly difficult dilemma, as leaving their assigned space is very risky.

Especially against the half-space defenders of an opposing three-man defense, this approach can be highly effective. By overloading the ball-far player in conjunction with the ball-near striker, a counter movement can be created that forces the defender to either press forward or drop back. This results in a deeper or dropping-off passing option being created.

The inward movement of central players into the half-space also creates a dilemma for their opponents. Particularly when a buildup player is in possession, shifting one or more central players into the half-space can force the opponent to open spaces in the center. This opens up passing lanes to the ball-far striker and winger, who can drop into the free space. This allows multiple layers to be bypassed.

Impact of Opponent’s Pressing Variations

Half-space overloads are effective regardless of the opponent’s defensive setup. They can work against pressing in defense, midfield, and attack, as well as against deep-lying teams.

However, their particular strength lies against compact teams. Half-space overloads are especially effective here because they force the opponent into unfamiliar movements. The specific characteristics of this space make it easier to create goal-scoring opportunities.

Player Profiles

Players like Wirtz or Musiala, who excel in playmaking and dribbling but are less effective in high-speed 1v1 situations on the wing, particularly benefit from overloads in the half-space. On the wing, these players may struggle to overcome their defenders, while in the center, the high opponent pressure makes it difficult to bypass defenders. However, in the half-space, they can fully exploit their creative strengths, as this area offers more freedom of decision compared to the wing and more space and time than the center.

The overload in the half-space creates numerical superiority, making it easier for these players to create goal-scoring opportunities or uncover spaces that they can exploit from the half-space.

The combination of two players with these qualities—like Musiala and Wirtz—presents significant problems for compact opponents. By positioning players in the left and right half-spaces, both half-spaces can be quickly and alternately overloaded. When the opponent is drawn to shift, the ball can be played from the overloaded half-space to the underloaded, free half-space, where the other creative playmaker can be found. The German national coach Nagelsmann already positions Musiala and Wirtz in these spaces.

Similar to how central overloads can pull defenders to the wings, allowing 1v1 strengths to emerge, a half-space overload can pull the opposite half-space free. Therefore, it might be beneficial to position players like Musiala in the ball-far half-space at times, providing more space and time for creative play. Half-space-to-half-space switches, as described above, would be most effective with the combination of two creative and dribbling-strong playmakers.

Summary

Half-space overloads are particularly effective against compact opponents. The unique characteristics of the half-space can be fully exploited through overloads. Additionally, playmakers like Wirtz and Musiala greatly benefit from these overloads.

Overload of the Wing

Functionality

Wing overloads are less effective due to the limited decision-making freedom of players because of the boundary of the touchline. From the opponent’s perspective, an overload on the wing is easier to defend than in the center, as fewer directions need to be covered. Moreover, wing overloads diminish the strengths of most wingers, such as fast 1v1 dribbling, which requires more space.

However, wing overloads can make sense in certain situations. The main advantage here is not so much the numerical superiority but rather the creation of space in central areas in the final third.

The Opponent’s Dilemma

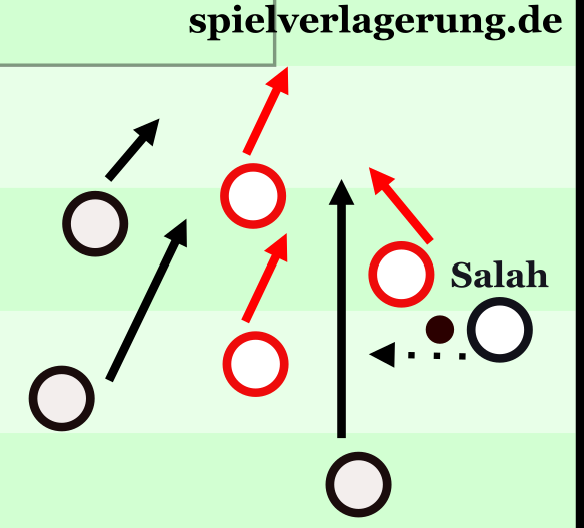

When overloading spaces on the wing, the opposing team must particularly cover runs into depth. If the players near the ball make runs into space, the opponent faces the dilemma of either securing the depth and drawing attention away from the center, or allowing passes to the wing behind their defensive line.

Liverpool exploits this form of overload in the final third to create space for Salah in the middle. The runs of the ball-near full-back, midfielder, and striker into depth towards the wing draw the central defenders out of the space that Salah prefers.

Player Profiles

As already mentioned, dribbling-strong wingers who cut in on their stronger foot benefit from overloads. The dribbling player is provided with a clear path towards goal.

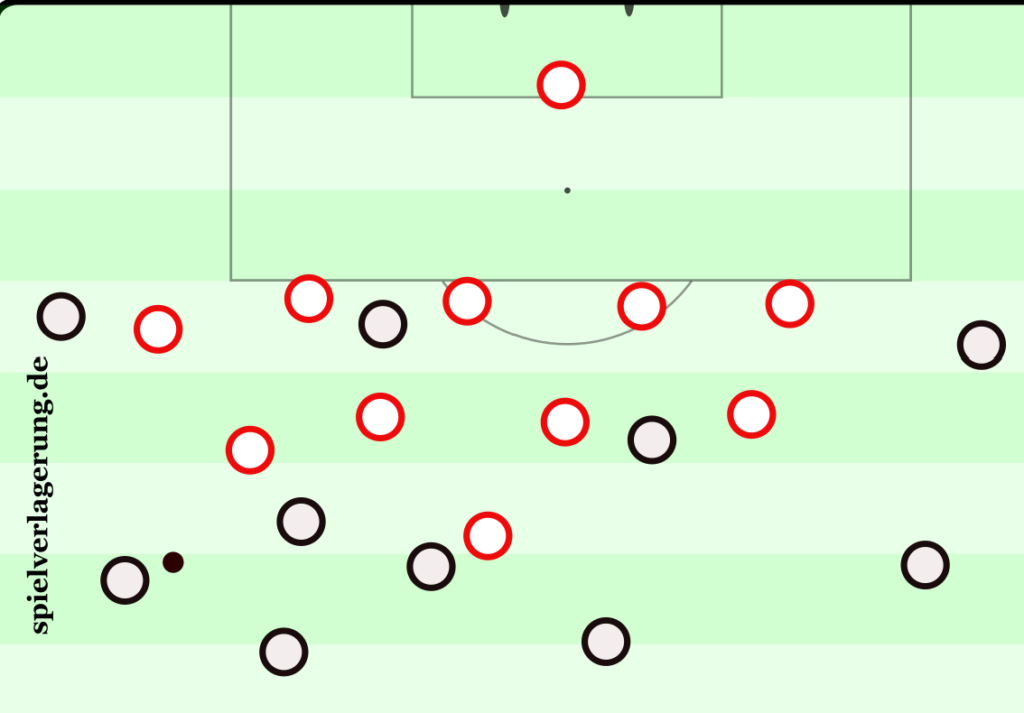

Overloading the Space Between the Lines

Functionality

The space between the lines is located between the opponent’s defensive lines or chains. Players can free themselves from high opponent pressure in this area by creating more distance from their markers.

The space between the lines is not a fixed zone on the field; it changes depending on the opponent’s structure. Therefore, the characteristics of previously described overloads of specific zones can overlap with those of the space between the lines.

Overloading the space between the lines can logically only be used fluidly, as opposed to occupying the area with individual players. Permanent collective occupation of this space is not possible because the opponent can shift together, thereby altering the spaces.

Overloads of the space between the lines are located only a few meters from the opponent’s defensive line but have a different effect on the opponent. For this reason, it is necessary to consider the space between the lines as a separate overload zone.

The Opponent’s Dilemma

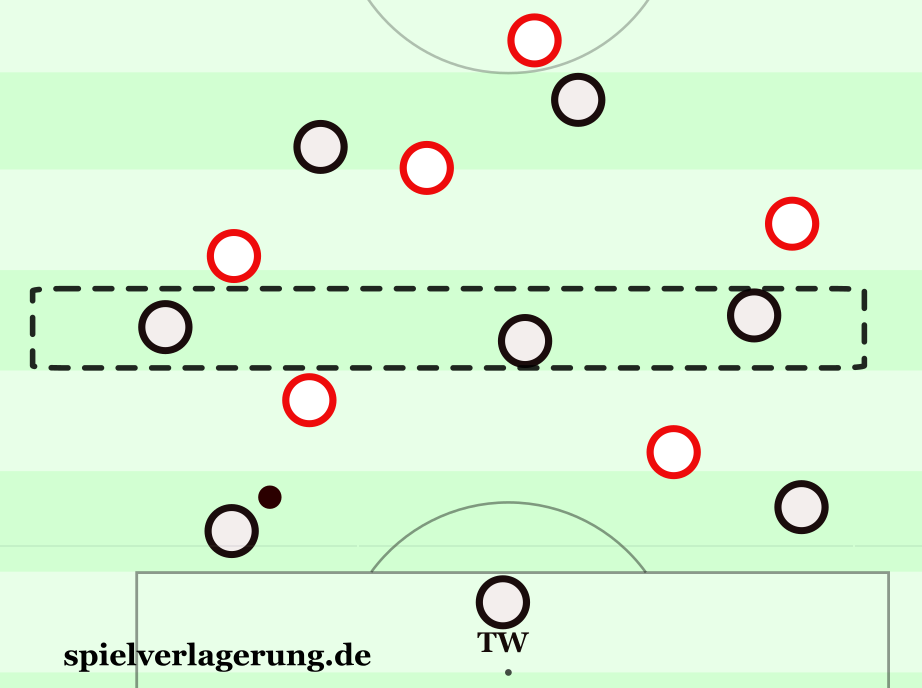

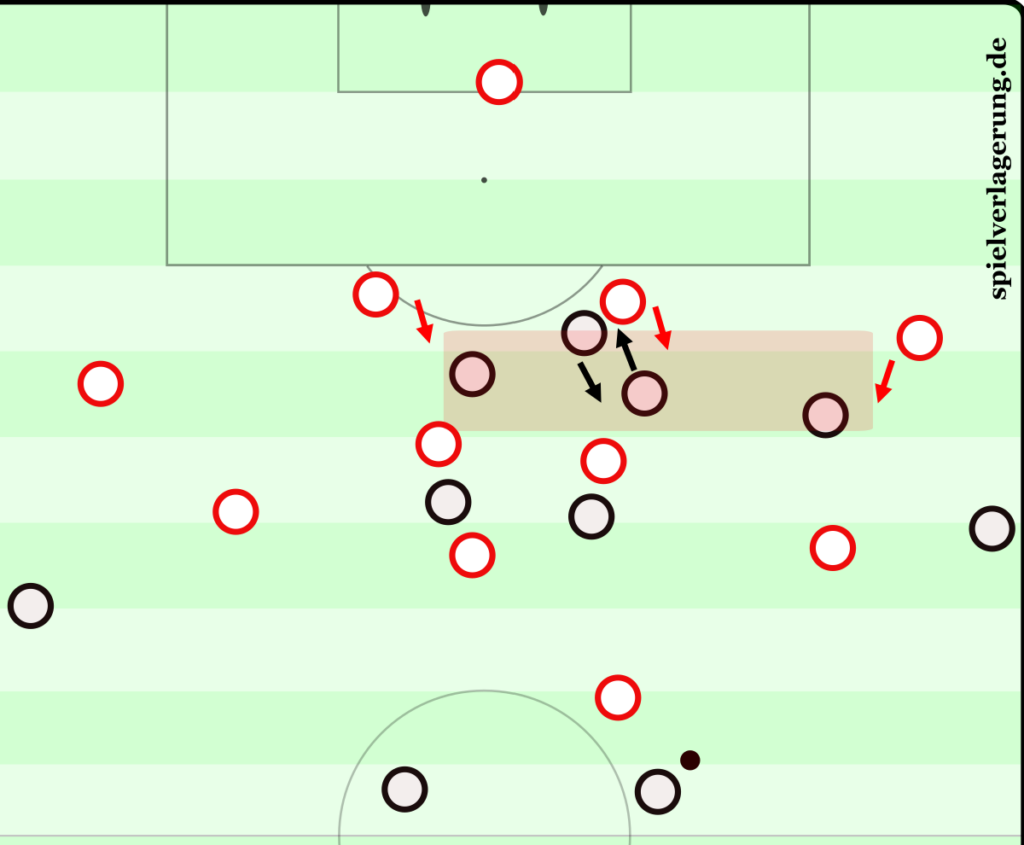

Overloading the space between the lines creates the following dilemma: the defenders must choose between pressuring the ball carrier and maintaining compactness to avoid opening passing lanes.

Particularly large problems arise when there are opposing movements starting from the overloaded space between the lines, as the defender is forced to make a decision. To create this dilemma, an overload in the space between the lines is necessary, which can be achieved through the strategic positioning of players.

Impact of Opponent’s Pressing Variations

Against opponent’s high pressing, it is useful to overload the space between the lines just behind the first pressing line. This space is part of the build-up zone, so the advantages and disadvantages are quite similar to those found when overloading your own build-up line.

It becomes particularly interesting to overload the space just in front of the opponent’s defensive line. The effect here is that defenders are forced to step out, opening up space behind the defensive line. However, against high defensive lines, overloading the space between the lines has a significant drawback. The opponent can push their defensive line higher, making the field more compact and narrowing the space between the lines. This leaves less time to escape the pressure.

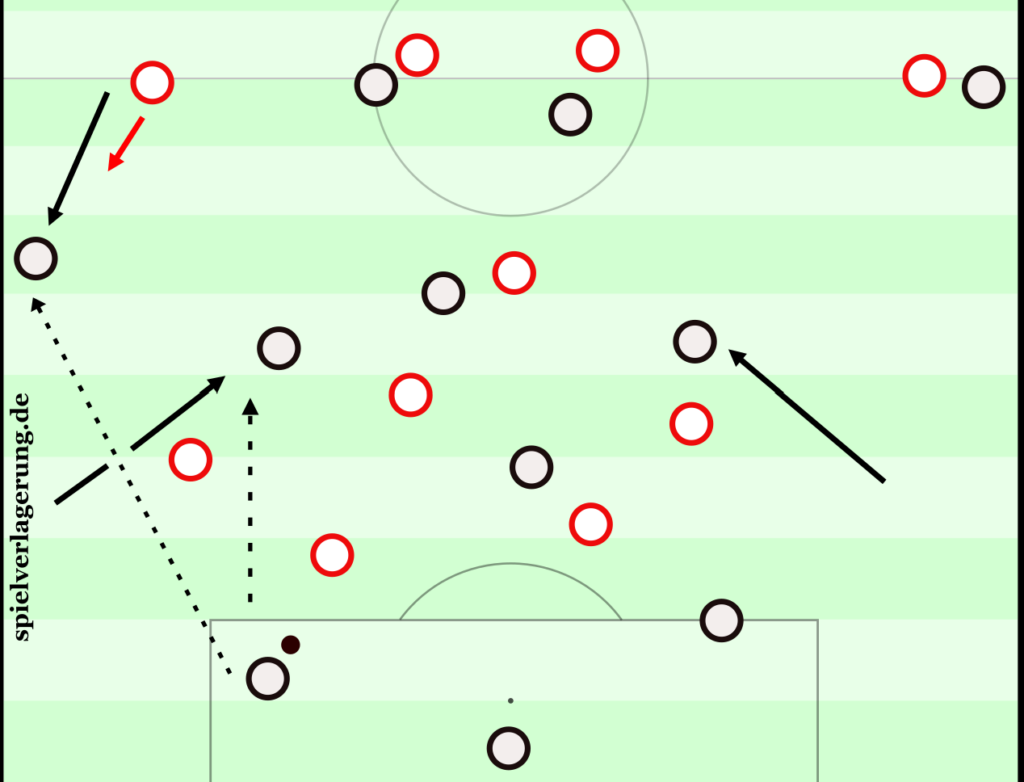

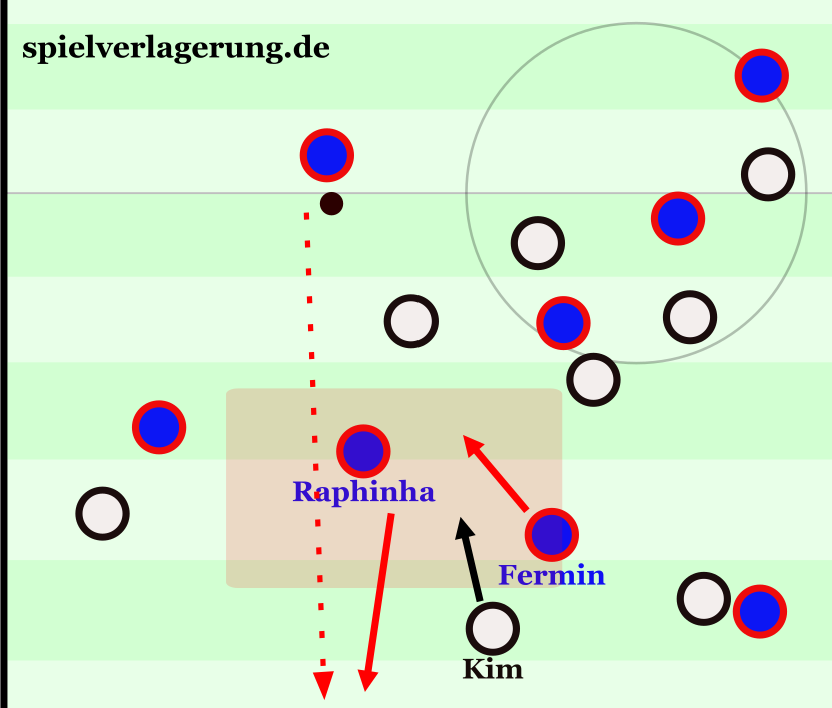

Still, overloading the space between the lines can be effective against a high defensive line. Following the “lure and shock” principle, this can be achieved by dropping midfielders to create as much space as possible between the midfield and the forwards. The attackers then move into this newly created space, forcing the defenders to step out. This creates a passing option or the free space can be exploited by a full-back or central midfielder.

Against deep-lying opponents, overloading the space between the lines can be very effective. The opponent’s defensive line aims to defend depth and maintain compactness. However, when the space between the lines is overloaded, defenders are forced to step up or not apply pressure on the player. This creates space behind the defensive line or provides passing options in front of the opponent’s defensive line. Overloading the last defensive line, as described above, is less effective in this scenario.

Player Profiles

Similar to the half-space, the space between the lines is a zone that combines decision-making freedom with less opponent pressure. As a result, creative playmakers particularly benefit, as they can evade their defenders in this space while enjoying strategic freedom.

Summary

The space between the lines depends on the opponent’s defensive setup and can therefore change. This makes situational occupation necessary. Problems arise for the opponent because shifting movements are provoked. In particular, deep-lying teams can be effectively played through by overloading the space between the lines in front of the opponent’s defensive line.

Overload Combinations

The described overloads can be applied not only in isolation but also simultaneously. A previously mentioned possibility is overloading both the own build-up line and the center. This way, maximum control over possession can be achieved.

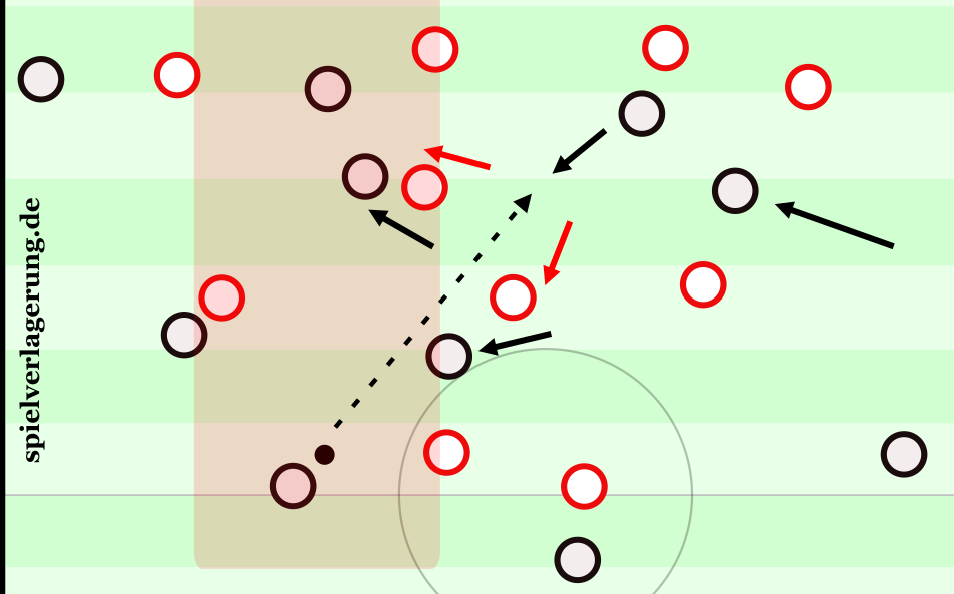

The overload of both the half-space and the space between the lines can also be effective when applied together. In particular, the junctions between these two spaces in front of the last defensive line are difficult to defend when overloaded. This could be especially useful for creating depth against compact, deep-lying opponents. It combines all the advantages of both half-space and between-the-lines overloads. These “golden zones” are a key to breaking through compact systems, such as 5-4-1, 4-5-1, or 5-3-2 formations.

Additionally, overloads in the center, paired with overloads in the final line, are an effective way to break through high defensive lines. Starting from the center, quick and short diagonal runs can create depth into the final line. Conversely, it also works the other way around to reinforce the center. Due to the shortness of the runs, the opponent has less time to react. At the same time, by overloading the center, a strong counter-pressing is immediately initiated in the event of a ball loss.

Principles of Play for Overloads

To implement such complex tactical considerations quickly within the team, it is advisable to rely on principles of play. This could involve differentiating between principles for creating overloads and principles for exploiting overloads. The principles for creating overloads may vary depending on the coach’s philosophy.

Possible principles for creating overloads (Philosophy / Game Objective – Control through possession):

- Pressure on the ball-playing player determines the overload/player number in the buildup zone.

- Seek overload in the center.

- …

Possible principles for creating overloads (Philosophy / Game Objective – Vertical possession play):

- An opponent’s high defensive line requires at least +1 in the opponent’s last line.

- An opponent’s deep defensive line determines the occupation of the between-the-lines space.

- An opponent’s tight spacing between lines requires at least +2 in the half-space.

- …

Possible principles for exploiting overloads:

- Look for diagonally opposing movements on the last line / in the half-space / in the between-the-lines space.

- Lure and shock (trigger pressing / shifting and playing into the free space).

- Create diagonal passing options in the center through height stagger.

- The closer to the ball, the more movement from teammates (effective layoff play).

- …

Conclusion

Asymmetries are harder for us to understand due to their lack of logic compared to symmetries. An asymmetry creates chaos for the opponent. From this consideration, it can be concluded that overloads (= asymmetries) in possession are particularly helpful in creating goals.

Overloads are the future of football, as they can help create depth in possession, generate goal-scoring opportunities, and challenge the opponent, especially against compact teams. A central element of overloads is generating dilemmas for the opponent. Depending on the overloaded space, different advantages and disadvantages arise. These must be strategically applied according to one’s playing philosophy.

It is highly likely that, in the future, we will witness more attractive and high-scoring games, as compact defensive lines can be broken more easily through various asymmetries, and offensive play will become much more multifaceted.

Author: MH is a football aficionado at heart. His apartment resembles a football library, with shelves filled with books on the great tacticians from Rinus Michels to Pep Guardiola. Of course, the book from Spielverlagerung.de is not missing. For MH, football is not just a game, it’s a way of life. He can be found on X under Mh_sv5 and LinkedIn.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen