Analysing Celta Vigo under Eduardo Coudet

On November 12th, 2020, following a start to the season with just one win out of their first nine, Celta Vigo fired Óscar García and replaced him with 46 year old Eduardo Coudet. In the two months following his appointment, Celta strung together an incredible run of results while implementing a style of play that captivated many fans.

Despite the promising start of Coudet’s tenure, Celta were brought back to reality after losing in the second round of the Copa Del Rey to the third division side UD Ibiza, by a humbling scoreline of 5-2. Since the Copa Del Rey exit, Celta’s weekly performances have contained dramatic undulations that have prevented them from solidifying a European place. Case in point: a three match winless streak in mid-April was followed by five furious wins, but the loss to Betis on the final matchday left them in 8th place as the best of the non-European qualifiers.

Nonetheless, there are many fascinating concepts that Coudet has ingrained into his side within his 4-1-3-2 formation. This piece will dive into these concepts, detailing specific qualities of Celta Vigo’s play throughout the phases of the game.

Deep Build-Ups

Celta’s primary objective becomes obvious within the first few meters of the pitch: pull the opposition forward in order to create space higher up to progress into. As such, Celta builds with a high quantity of players close to their own area – forcing the opposition to either press with many numbers or retreat. Celta’s centre-backs, most commonly Nestor Araujo and Jeison Murillo, position themselves narrowly and deeply, slightly higher than that of the goalkeeper, in order to avoid a horizontal-lined pass as the first step of their build-up. Celta’s fullbacks, Hugo Mallo and Aarón Martín, also start deep, which creates a direct passing lane to the centre-backs while also reducing the time the pass takes between the centre-back and fullback. These short passes engage a complete commitment of the opposition’s pressure, far into Celta’s own half.

The question must be posed: Why do Celta want the opposition to press? The answer is quite clear – the opposition’s forward momentum attained through high pressure further enhances the positional advantage for a Celta player arriving beneath a higher receiver. Celta’s set up of a 4-1-3-2 naturally positions three players between the second-to-last and last line of the opposition; therefore, if the opposition’s second-to-last line is forced to move a large distance forward in order to press, Celta’s advanced midfielders will have more space (time) to work with upon receiving, thus optimizing their positional superiority. Once the ball eventually arrives to said advanced midfielders between the lines, numerical superiority is generated, as Celta’s two forwards can create advantageous duels by making runs that manipulate the defenders’ positionings within the overall 5v4 or 5v5. Celta’s forwards thrive in situations like these – specifically ingenuitive attackers like Iago Aspas and Brais Méndez – who are free to show their tremendous qualities in 1v1 situations.

As mentioned before, in order to fully attract the opposition’s pressure, Celta occupy deep positions in their buildups. Specifically, the deep nature of their fullbacks enlarges the jump that is required for the opposition’s wide player to apply pressure to the fullback, thus opening a larger space that Celta can use to progress. Celta often deploy bait movements in and around this space, with the intention to make an opposition player leave his position in order to reduce said space – and consequently open up passing lanes to those higher up the pitch. In addition to the opening of these passing lanes, this jump from the opposition’s player generates more space for Celta higher up the pitch.

However, it is not to say that these bait movements are not fruitful for he who makes them himself. If the opposition does not track the runner, the runner can form a passing lane with the fullback within the enlarged space – meaning the fullback has an option to surpass the immediate pressure. After completing this pass, Celta’s fullbacks often make an immediate secondary movement forward into the space vacated by his presser, supplying Celta an additional player in the area around the ball.

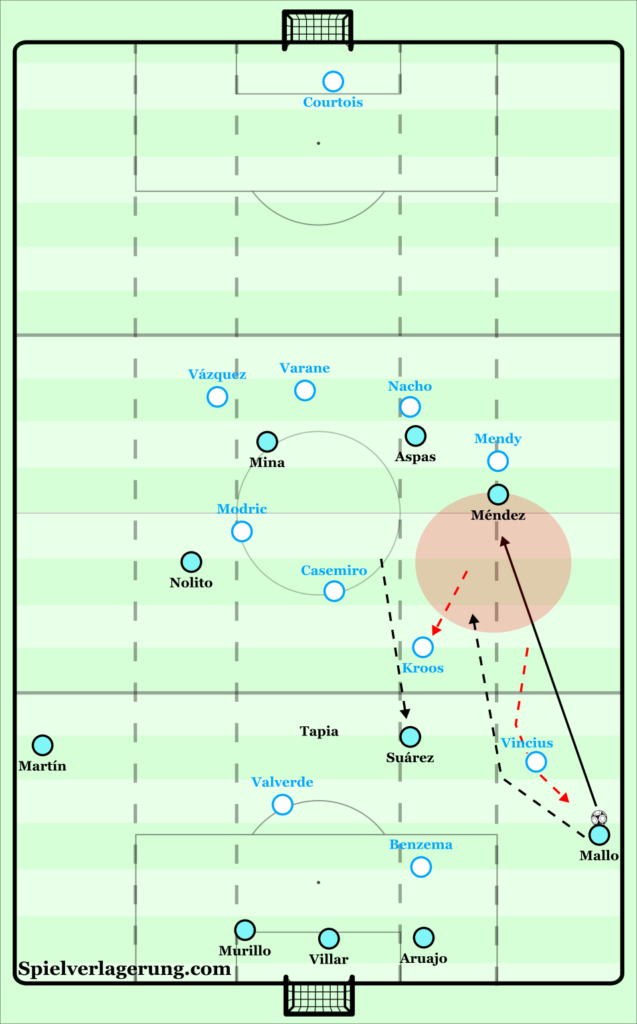

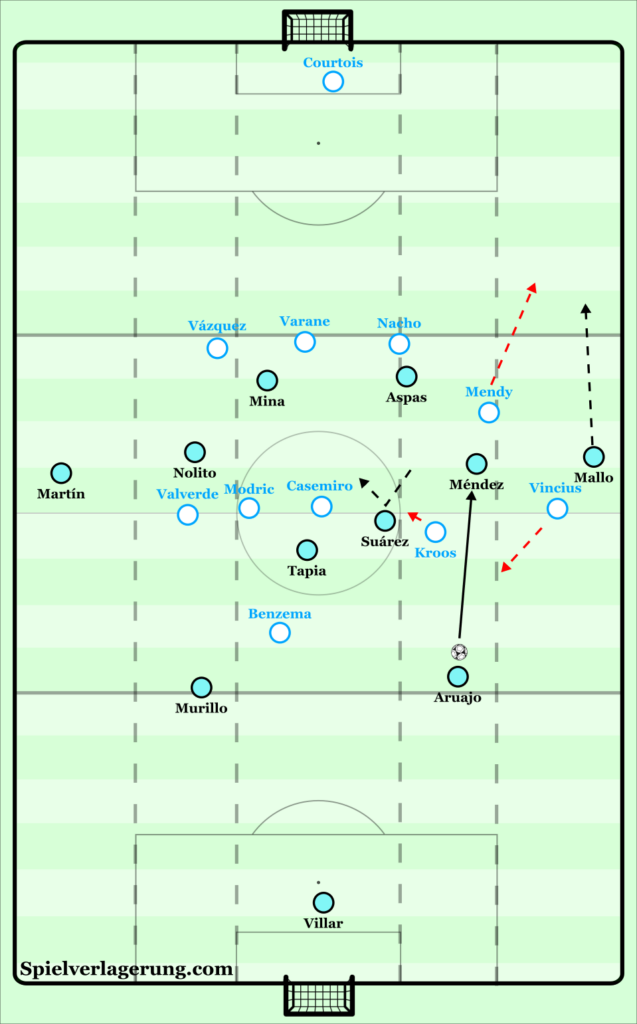

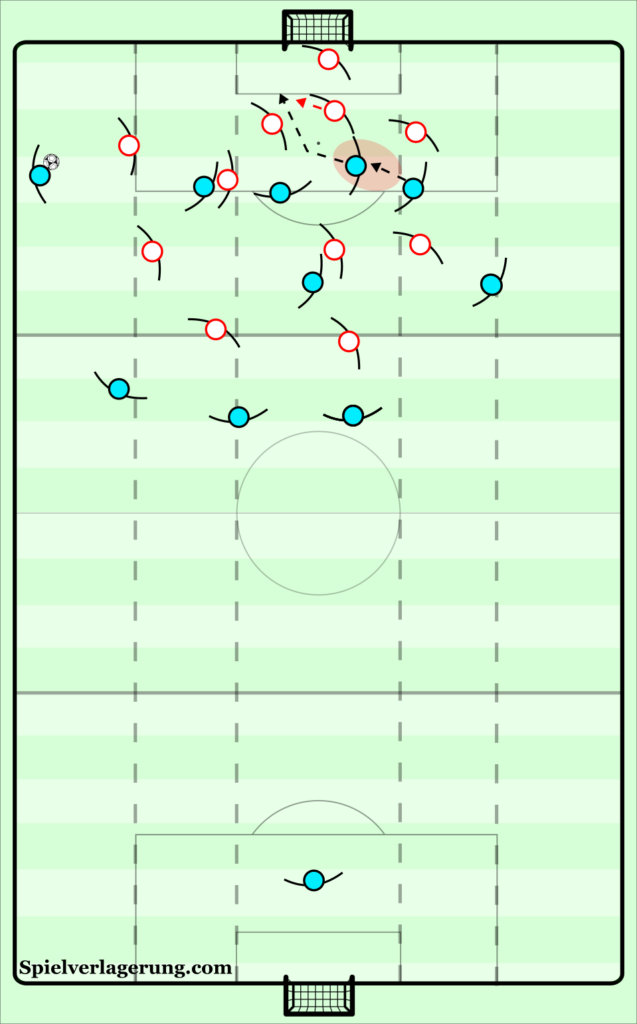

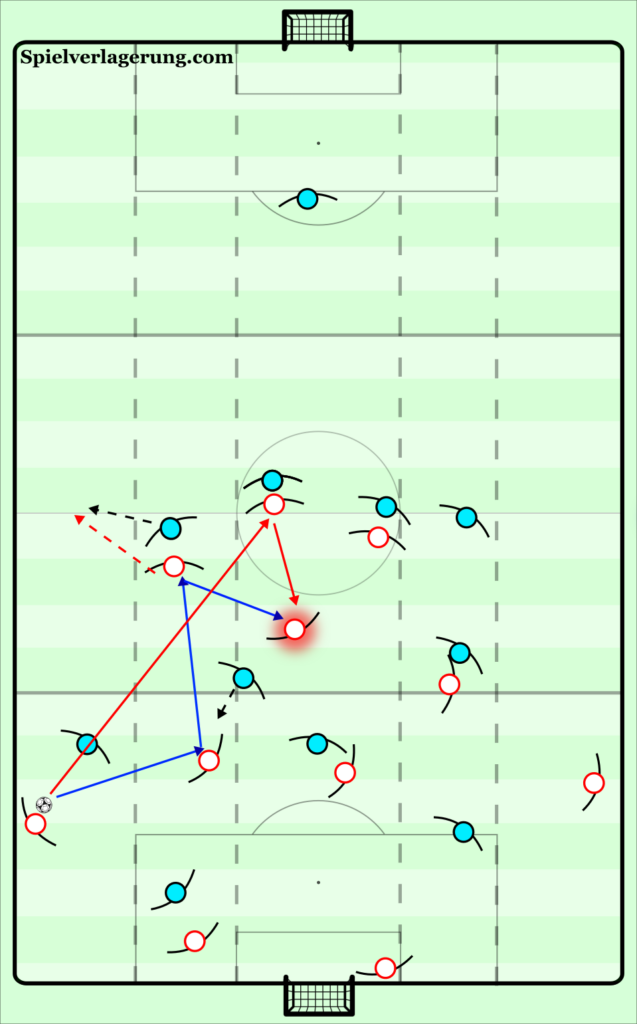

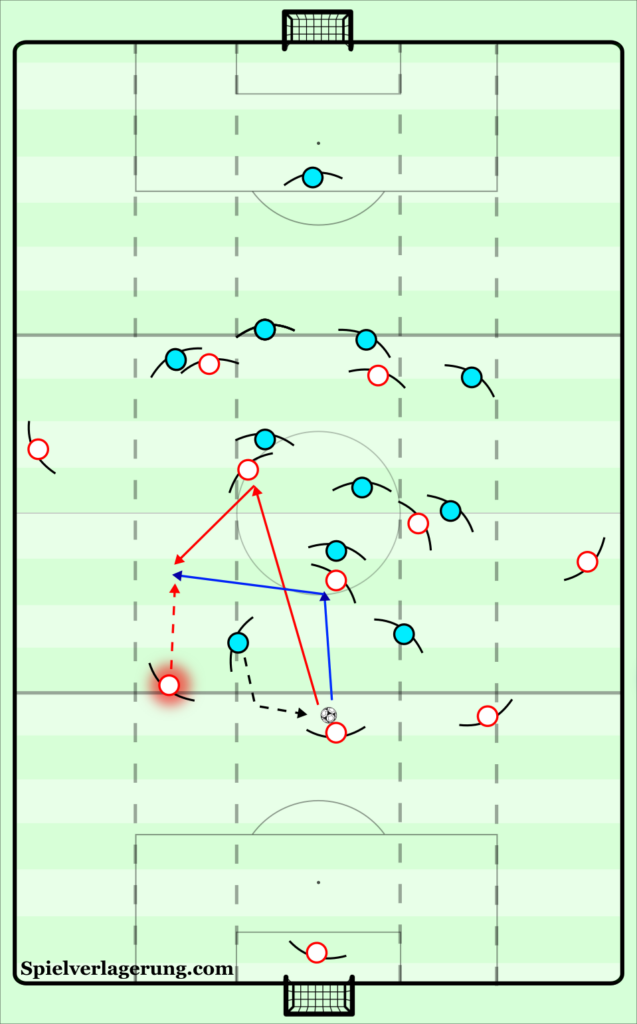

The advantages of the deep fullback can be shown below in the image of a Celta build-up against Real Madrid, who press in a 4-5-1. Araujo receives the goal kick from Iván Villar, engaging the pressure of Karim Benzema. As Araujo is the right centre-back, the right-back, Hugo Mallo, drops the height of his position even farther in order to form a shorter passing line with Araujo. As the centre-back plays the ball wide to Mallo, Denis Suárez, the advanced central midfielder, shows deep to provide a central passing option – dragging Toni Kroos out of position. As Kroos vacates the space, this increases the distance between the German midfielder and Real Madrid’s backline, generating space that Celta desire to arrive into. Vinicius then applies intense pressure onto Hugo Mallo – however, he is forced to adjust the angle at which he presses in order to cut off the central passing line to Denis Suárez. Therefore, due to the triangle formed around the ball by Celta’s players, Mallo is able to play the ball vertically into the feet of the right-midfielder, Brais Méndez, who is arriving into the space vacated by Kroos.

Although the ball has progressed past the initial pressure of Real Madrid’s first and second lines, Brais Méndez is in a difficult situation – he is receiving with his body orientated towards Celta’s own goal, with intense pressure being applied on his back by Ferland Mendy. The solution, once again, comes from the deep fullback: Vinicius’ run in order to pressure the deeply positioned Mallo has to be a sprint, as the increased distance provides Mallo more time on the ball. This uncontrolled sprint permits Hugo Mallo to move around and past the Brazilian winger after he plays the ball into the feet of Brais Méndez, thus becoming the free man that can arrive beneath the under-pressure Brais Méndez. From here, the wing pair can play 2v1 against Mendy and surpass his presence through another third man combination: as Mendy is obligated to apply pressure to the ball (due to Real Madrid’s line of confrontation already being met), Brais can make a movement with the thought of receiving as the third man from a teammate who is positioned at a higher height of the pitch. With the adequate positioning of the forwards, Mallo is able to connect to Celta’s highest line, who can set to Brais Méndez, who can then attack Madrid’s last line.

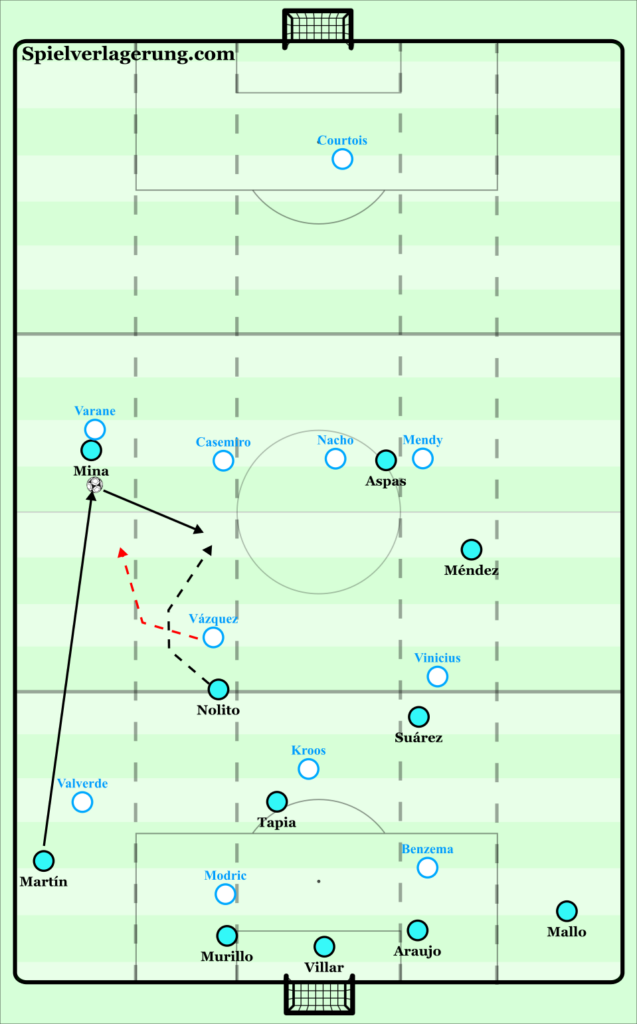

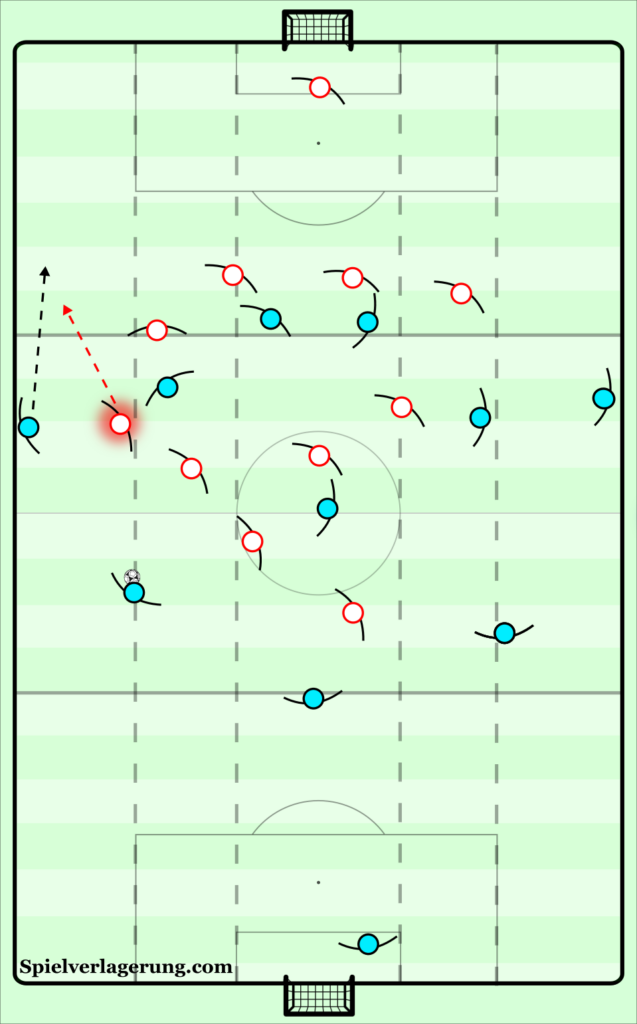

Another sequence from the match against Los Blancos further captures the usefulness of deep fullbacks. As Celta play out, Jeison Murrillo passes to a deeply positioned Aarón Martín. This short pass cues a movement from Celta Vigo’s left midfielder, Nolito. Nolito, who starts from a high and wide position within the left half-space, shows deep and inside to provide a central option. As Madrid are attempting to keep Celta pinned within their own half, Lucas Vázquez, Madrid’s right back, is tasked with tracking Nolito deep in order to prevent Celta from generating numerical superiority around the ball; however, the attraction of Vázquez centrally frees space vertically up the left touchline. This space can be occupied by Celta’s left forward, Santi Mina, who makes a movement wide into said space. Martín plays the pass into Santi Mina’s feet – however, as he is receiving facing his own goal and pressure on his back from Raphaël Varane, sustainable progression has yet to be achieved. To make matters potentially worse, Lucas Vasquez is able to fall back onto Mina, creating a 2v1 with his French teammate against Celta’s forward. However, as a result of Vázquez falling back, Nolito is now the free man. By making an initial, short movement to the left of Vázquez, Nolito tricks Vázquez into opting to position his cover shadow to block a pass to the left. Intelligently, Nolito then elects to explode to the right, out of the right back’s cover shadow and providing a progressive option to Santi Mina.

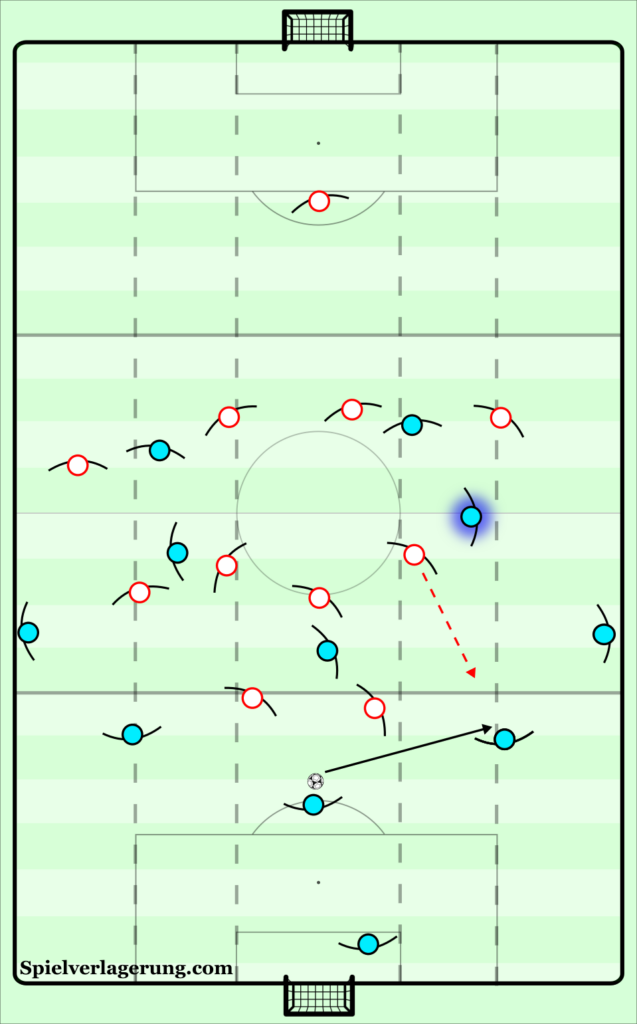

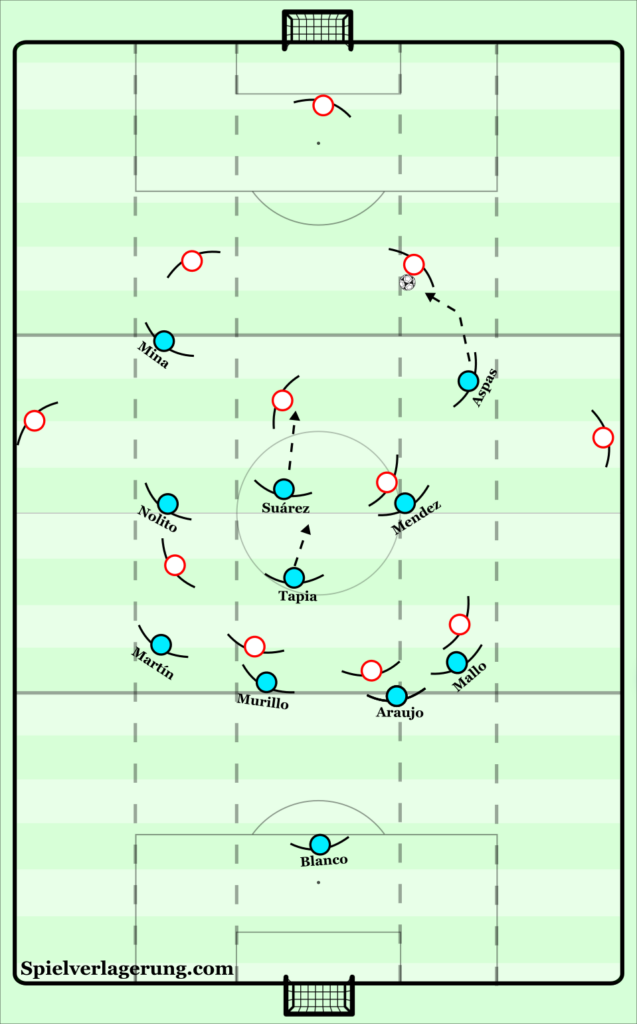

Despite the generation of advantages that the deep fullbacks furnish, Celta have a great capacity to tweak their build up to further their efficiency of achieving territory higher up the pitch. As shown in the image below, Celta have the flexibility to drop Renato Tapia, the single pivot, in between the two centre-backs. As a result of the width of the newly formed back three, Celta’s fullbacks obtain the license to be positioned at a higher height, past the opposition’s first line of pressure, while still maintaining a short passing line with their respective outside centre-backs. Denis Suárez then will position himself as the single pivot, providing a depth centrally to the first lines of Celta’s structure. The presence of a single pivot manipulates the opposition’s forward line, as they are now obliged to always screen the passing lane centrally to Denis Suárez in order to prevent their first line from becoming easily surpassed – freeing Celta’s opposite centre-backs. As a result, Celta’s circulation of the ball becomes more fluid.

That said, in order to prevent a free Celta centre-back from constantly receiving with space to commit after a circulation, the opposition are forced to commit a midfielder to Denis. This jump permits their forwards to maintain a wider position across the first line, shortening the distance that the forwards must travel in order to pressurize the centre-backs. However, the staggered nature of Celta’s back three prevents the opposition’s two forwards from cutting off access to each of Celta’s three centre-backs. Therefore, Celta look to circulate until a centre-back receives in adequate space to commit past the first line of the opposition’s pressure.

The drive of Celta’s centre-back past the first line of pressure engages another opposition midfielder to step forward out of his position – thus creating a substantial amount of space between the opposition’s midfield and defensive lines. Therefore, Celta’s advanced midfielders have more space to receive – either directly from the centre-back or as the third man off of a set from the forward. In order to make this reception a possibility, the positioning of Celta’s forwards is critical. The occupation of the highest height within the channels is optimal, as it pins back the opposition’s central and wide defenders from stepping in an attempt to close the enlarged space between the lines. If the defender were to jump to close the free man in between the lines, the position of the forwards in the channels permits a movement into the space vacated by the defender: in behind the opposition’s last line.

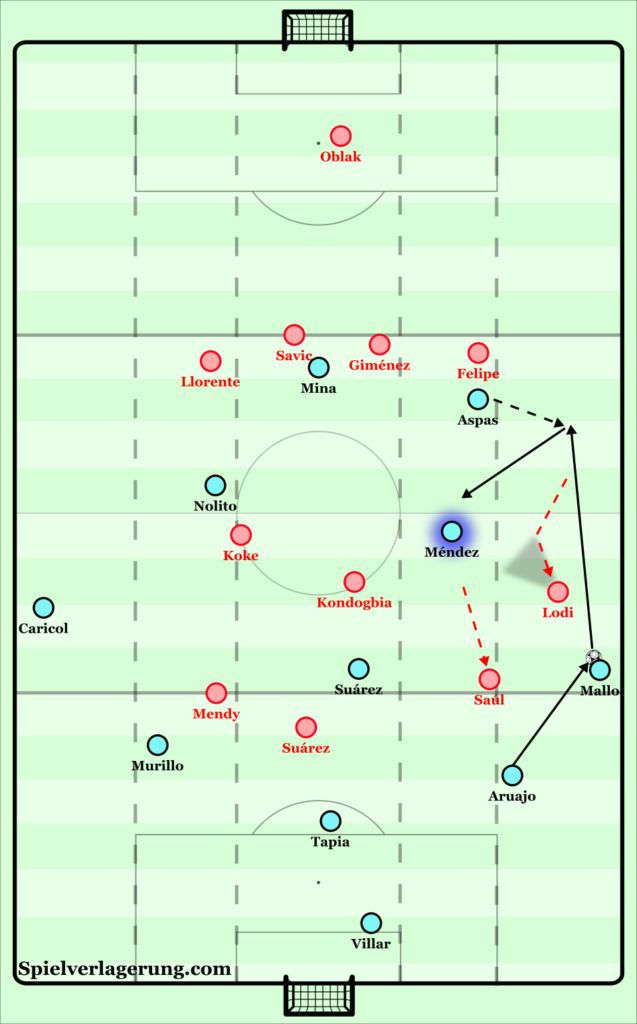

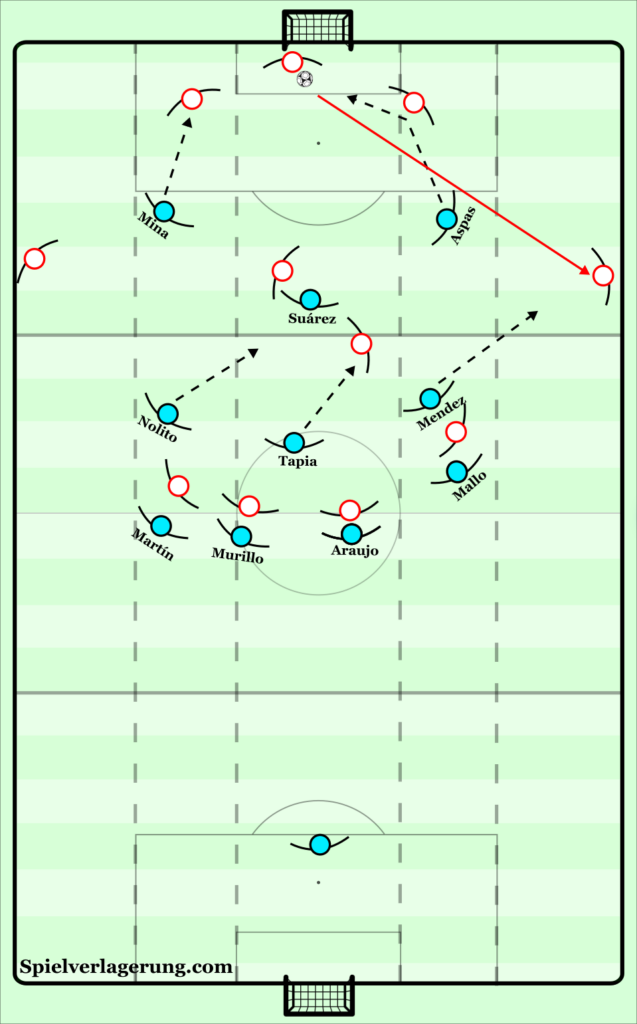

As shown in the image below, against Atlético Madrid’s 5-3-2 high pressure, Celta Vigo opted to drop Tapia between the two centre-backs, permitting Mallo and Martín to take up a higher height. The circulation across Celta’s three players ends at the feet of the free man, Araujo, who receives in ample space on the side of Atléti’s forward line. As the line of confrontation has already been met, Saúl jumps to close down the space around the ball. This leaves Atletico with just two midfielders to cover the remaining four of Celta, who are positionally staggered across separate heights. As the ball arrives to Araujo, Mallo drops deep to lengthen the distance between himself and his rival, Renan Lodi – therefore giving himself more time after the reception of the pass. After the ball is at the feet of Mallo, in order to prevent a simple connection from the fullback to the pivot – which would take out four of Atlético’s players – Geoffrey Kondogbia must step to eliminate Denis Suárez. This jump from Kondogbia frees Brais Méndez from a midfield marker of Atlético. Due to the optimal positioning of Iago Aspas, Atlético’s centre-back and wingback are also unable to approach Brais Méndez without leaving space in behind – making Méndez become the free man with a lot of space to receive in. As the ball arriving at the feet of the free man in a position as such is immensely threatening, Atlético naturally takes this into account when pressing – meaning that Brais can be key in manipulating the area that the ball presser chooses to block with his cover shadow. In this scenario, as he starts from within the half-space, he is able to move into the space off the inside of Lodi, manipulating the Brazilian fullback into blocking the central area with his covershadow. This opens a vertical passing lane down the sideline for Aspas to arrive into, who receives the pass from Mallo. Despite having pressure on his back, progression past Atlético’s midfield line is able to be achieved through a set to the free man in Brais Méndez, who can drive forward and attack the back line of Atlético.

Overcoming A Mid-Block

Upon encountering a block with a lower line of confrontation, naturally, it appears more difficult for Celta to generate expanded spaces between the opposition’s midfield and defensive lines. As a large number of the opposition’s players are less likely to step forward to close down the ball in order to conserve vertical compactness, mid-blocks pose a great challenge to Celta’s objective. For this reason, Celta implements a structural rule to aid the arrival of the ball into the free men between the lines.

An essentiality of Celta’s structure in the middle third of the pitch is the avoidal of vertical lines containing more than one player in reference to the position of the ball. This creates numerous passing lines for the ball possessor to decide between, as one opposition player is physically unable to mark two or more of Celta’s players. As a result, the opposition is forced to narrow their defensive lines – opening space on the flanks for Celta’s fullbacks to move into and receive the ball. As the presence of the ball in wide areas is synonymous with the opposition’s players being forced to retreat (as one is able to access the space behind the opposition’s last line due to the angle at which a pass would arrive), occupying central positions in order to move the ball to the space on the flanks is a feasible way for Celta to achieve their goal of pitch progression.

Another advantage that the avoidance of multiple players within one vertical line generates is the ability to carry out clean third man combinations. As Celta’s lines generate multiple layers, the capability to execute such combinations is almost always there; however, without the presence of said vertical lines, the third man arrives underneath the second man at an angle that does not equal 180 degrees – making the set easier to receive as the third man. Not only does this facilitate a more controlled, rapid passing between Celta’s players during the combination, but it also generates a more advantageous 2v1 between the second and third man. As the third man is receiving the set with momentum away from the second man, an angle capable of progression is formed between the two Celta players – maintaining two distinct heights (in front and behind) the opposition’s defensive line. The occupation of the space just off the back of the defender manipulates the position that the defender is able to take up – opening more space for the player in front of him to work in.

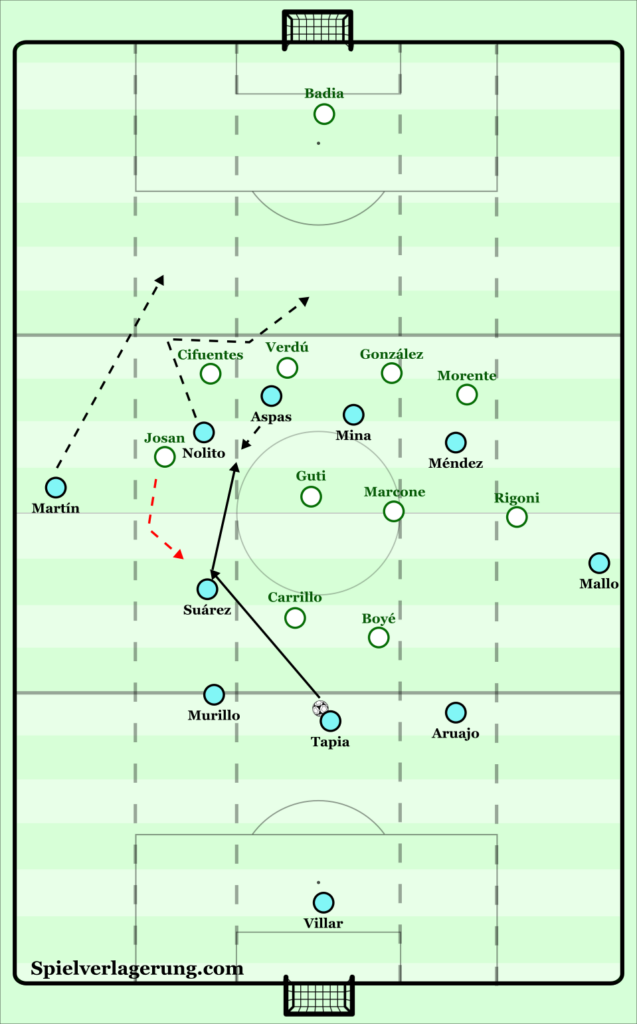

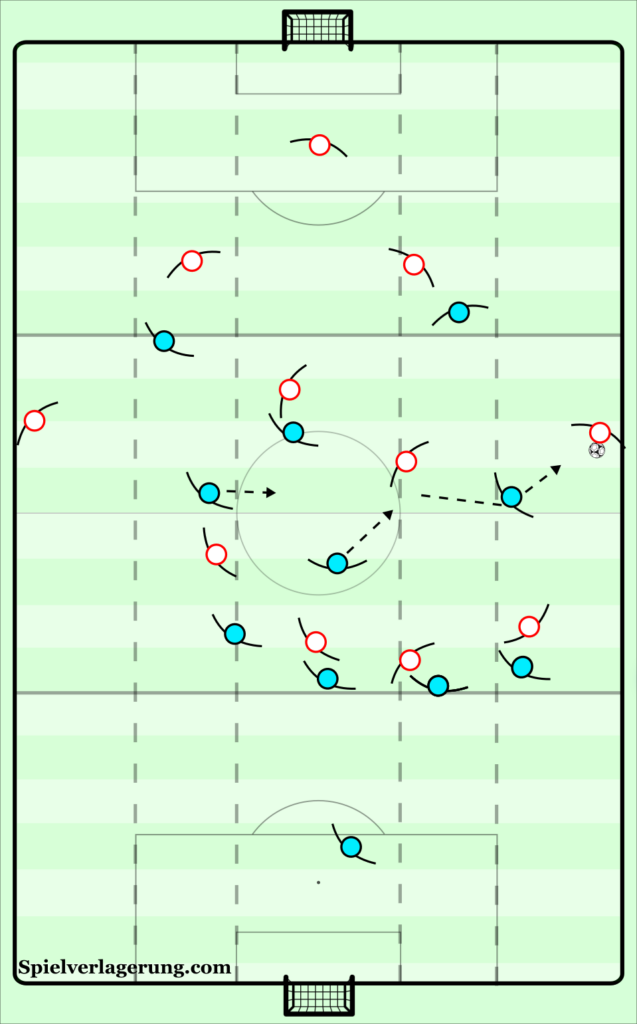

In order to achieve the aforementioned advantages, many automatisms are implemented that abide by this rule while also incorporating interchanges of positions. As shown in the image below, progression past Real Madrid’s 4-5-1 mid-block was achieved through one of these innovative automatisms. As the ball is circulated between the centre-backs, Denis moves just above Tapia, engaging Kroos out of his position – distancing the German from Real Madrid’s defensive line. In order to prevent Madrid’s defensive line from stepping up, Aspas maintains a position on the shoulder of Madrid’s left centre-back and left back. As a result of Aspas and Denis Suárez’s positions, Brais Méndez is able to occupy the space vacated by Kroos without a marker. As Karim Benzema is overloaded against the two centre-backs of Celta, a circulation can be executed to the free centre-back – in this case Araujo. He is then able to commit forward past the pressure of Benzema, cueing the commencement of the interchanges of height. Hugo Mallo, maintaining the width on the right touchline, begins to run forward, posing a question of his respective marker Vinicius: track the advancing fullback or leave Mendy in a 2v1 situation? As Mallo makes his run, Brais Méndez shows deep within the right half-space, orientating his body toward the centre of the pitch. Due to the width provided by Mallo, Vinicius is unable to cover both the wide passing lane to Mallo and the inside lane to Brais Méndez,. Vinicius opts to track Mallo, thus allowing Méndez to receive a pass from Araujo on his far foot and progress past the midfield line of Real Madrid.

Just as in their build-ups, Celta are flexible with the quantity of players within their first line. Celta generally opt for a quantity that is one player superior to that of the opposition’s first line of defense. It is common to see Celta drop Tapia or a fullback alongside the centre-backs to generate this initial superiority around the ball, intending to force an opposition player located within the second line to step forward – creating space and transferring the free man higher up the pitch. This jump of an opposition player from the second line is many times provoked by the commitment of Celta’s free centre-back, as this action obligates an opposition midfielder to step out of position in order to apply pressure to the ball. This naturally creates a space between the opposition’s midfield and defensive lines. Therefore, a committing centre-back is a cue for various automatisms that look to take advantage of the positional superiority that Celta’s two highest lines contain.

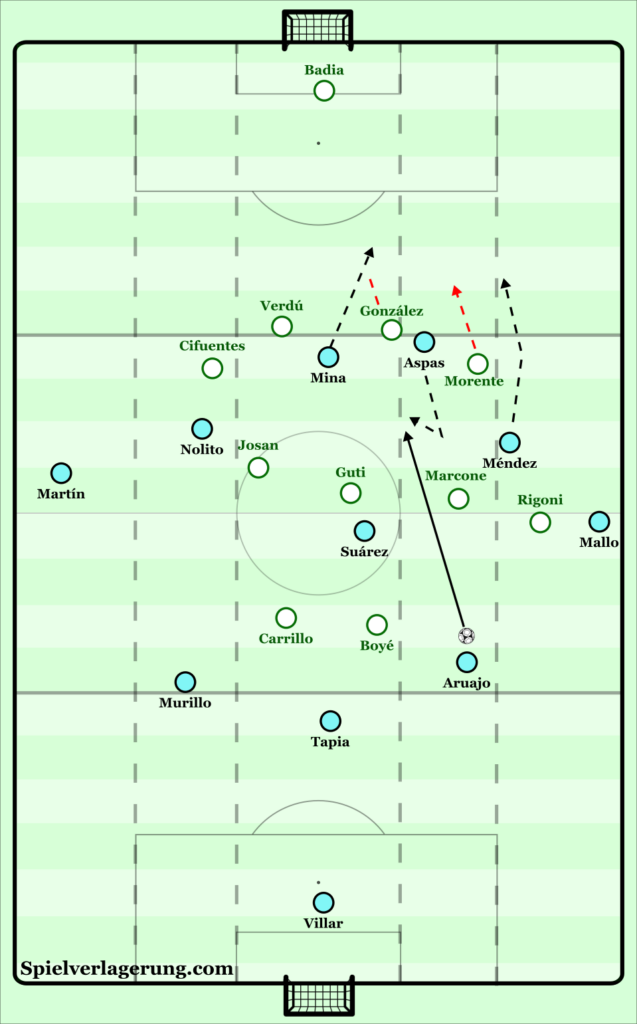

The importance of initial superiority within Celta’s attacks can be seen in the image below. Against Elche’s first line of their 4-4-2 mid-block, Celta creates the initial superiority of 3v2 by dropping Tapia into the back line. In turn, Araujo becomes the free man off the side of Elche’s first line, and after receiving off the circulation, he is able to drive forward past Elche’s first line. Knowing that an Elche midfielder will step out and thus a space between the midfield and defensive lines will appear as Araujo commits forward, Brais Méndez and Iago Aspas interchange their heights. Due to the starting positions of both Aspas and Méndez, this interchange is nearly impossible to defend; because Brais Méndez starts between the lines, he already has an advantage and therefore cannot be tracked by Elche’s midfielder: only Elche’s fullback. This then prevents the fullback from staying tight to Aspas, meaning that Aspas can find the optimal distance behind the Elche midfielder and in front of the Elche fullback. However, as he positions himself in this space, it is important that Aspas adjusts his body orientation in order to receive facing forward. Santi Mina’s movement into the space behind Elche’s last line is crucial, as it prevents Elche’s centre-back from stepping to Aspas. The arrival behind the opposition’s last line also forces the opposition to drop after Aspas receives, creating more space for Aspas to drive into.

The presence of a single pivot is another critical element of Celta’s play within the middle third of the pitch. Being that the positioning of the pivot is just off the back of the opposition’s first line, an advantageous height is added to Celta’s base structure that can be used to consistently overcome the opposition’s first line of pressure. Denis Suárez, in particular, is superb at reading the circulation to then move himself into positions that create direct passing lanes with the three centre-backs in order to receive past the opposition’s first line. As seen in the image below, against Elche’s first line of pressure, Denis Suárez drifts off the right side of Elche’s first line and receives on his far foot – crucially positioning his body between the Elche attacker and the ball. He is then able to drive forward, engaging Elche’s wide midfielder, who is forced to vacate Celta’s left back, Aarón Martín, in order to close down Denis. As Elche’s wide midfielder opts to cut the passing lane to Martín, Denis Suárez is able to connect with a central option. This opportunity is recognized by Celta’s players within the two highest lines, cueing Aspas to drop as Nolito makes a forward run – freeing Aspas to receive between the lines. Denis then delivers the pass to Aspas, who is able to turn and drive at the back line. Due to the vacation of Aaron Martín from Elche’s winger in order to pressure Denis, Martín is now the free man running forward. Elche’s fullback takes up responsibility of Martín, but because Nolito continues his forward run, Elche’s centre-back is then also pinned from confronting Aspas. Consequently, this pin also generates a central passing lane to Celta’s opposite forward in Santi Mina. Aspas is able to find Mina, which forces Elche’s right centre-back to rotate his hips to the centre of the pitch – creating space for Nolito to continue his forward run and arrive between the centre-backs for Mina to play him in behind Elche’s last line.

In order to limit the influence that Celta’s pivot carries, the opposition are forced to step a midfielder to the pivot to prevent constant overcoming of their first line by Celta. This jump to Denis creates space for one of Celta’s advanced midfielders to occupy deep. As a result, the opposition is heavily outnumbered both around the ball as much as across their midfield line. This shifts the emphasis to the backline to close down Celta’s players that are positioned between the lines; however, due to the pitch occupancy of Celta’s two forwards, Celta are able to exploit a jump from an opposition’s defender – arriving in behind the last line.

Upon arriving into the final third, Celta look to attack the channels. As a result of Celta’s fullbacks maintaining the width, upon a circulation into the wide areas, the opposition fullback is often forced to step out toward Celta’s fullback – creating a large gap between the opposition’s fullback and centre-back. This is often exploited by Celta’s wide-midfielder, whose narrow position provides a viable distance to arrive into the channel at the optimal time. This run from the advanced midfielder forces the opposition’s ballside centre-back to consider tracking the runner into the channel – which would leave dangerous space in the penalty area. However, if he were to choose not to follow the runner in the channel, the fullback and wide-midfielder would be able to work the 2v1 to arrive at the goalline, from where they can play dangerous cutbacks.

In relation with Celta’s principle of achieving pitch territory through sucking the opposition away from dangerous spaces to then attack said spaces, it is very common to see Santi Mina arrive at the near post. This movement attacks the space that the opposition’s centre-back vacates when stepping out to track the runner into the channel. Subsequently, the opposite centre-back is forced to track Mina to the near post in order to prevent a simple tap-in – creating more space in the area for the arrival of teammates.

The intention of Celta to disorganize the opposition’s defensive structure in order to arrive into dangerous space not only facilitates progression for Celta with possession of the ball, but it also makes the opposition’s task of maintaining the ball after recovery very difficult. In short, Coudet implements organization in order to inflict disorganization; the organization across many heights of the pitch generates positional superiority. As such, when the ball is lost, the layers that are present act as a block to inhibit the opposition’s immediate progression. Therefore, after turning the ball over, Celta are able to apply instant pressure to the ball from multiple angles. This increases the probability that Celta wins the ball back within the first few seconds of losing it, as the disorientated rival has a lot of chaos to overcome. In addition to the rival player being forced to take into consideration the multiple angles that he is being pressed at, he must connect with a teammate whose position may be altered as a cause of the disorganization of their defensive block inflicted by Celta’s in-possession movement.

An exemplary exhibition of this principle can be viewed through the wide superiorities that Celta generate. As aforementioned, the occupation of different vertical lanes centrally at distinct heights in reference to the ball oblige the opposition’s block to become narrow, therefore leaving space in the wide areas that a Cetla fullback can arrive into. As such, the opposition’s wide-midfielder is demanded to track Celta’s advancing fullback, diminishing the opposition’s counter attacking threat. As the opposition’s wide-midfielder moves wide to shorten the distance between Celta’s fullback, it is also true that he will leave space centrally that an advanced midfielder of Celta is able to occupy.

Despite the innovative in-possession concepts implemented by Coudet’s side, there are times when it can turn terribly sour. As Celta’s primary objective is to achieve pitch progression, there are instances in which those in the first line want to progress too quickly. On these occasions, the ball is forced forward after a few passes being connected between Celta’s players. As a result of the ball being rushed forward, the initial superiority that was generated at the base of Celta’s structure is unable to be transferred to higher heights of the pitch. This inhibits Celta’s players moving together around the ball, and thus diminishes not only the efficiency of Celta’s attack, but also the probability of Celta winning the ball back within a few seconds after they lose it.

Further issues in possession for Celta stem from poor decisions in their first line. After a Celta player progresses past the opposition’s first line of pressure, the player tends to struggle when electing the pass that would achieve optimal progression. Many times, the centre-back opts to play a pass directly to the free man between the lines – which does achieves progression; however, if the centre-back were to recognize that the forward could receive and set to the free man, Celta would arrive into the indefensible space with more threat – the free man is not only orientated toward the opposition’s goal, but he is also travelling forward. Passing to the feet of the forward also forces the opposition’s centre-back to step out and be engaged, thus expanding the space between the opposition’s goalkeeper and last line of defenders.

This is not to say that the centre-back must always elect the farthest forward option, but rather that he must interpret the context around him in order to identify which path is the one that will obtain optimal progression. Based upon who jumps from the opposition’s second line to confront the in-possession centre-back, he must take the initiative in the sequence. For example, if he identifies that the best pass to achieve progression is to the current free man between the lines, he must deliver the pass to the free man’s farthest foot, with the correct spin, at a pace in which the free man can turn. If he identifies that the correct pass is the one into the feet of the forward, it must be delivered to the foot farthest away from the forward’s marker, at a weight which permits a one touch set into the path of the free man. If the free man is unable to be reached due to the opposition’s condensed block, he must identify this immediately and play wide to further move the opposition.

Celta’s High Pressure

Just as in-possession, Celta rely on their centre-backs heavily in their high pressure. As Celta’s objective is to arrive into high areas, it is to little surprise that they prefer to be positioned high when defending. As seen in the image below, Celta’s formation for their high pressure can be labelled as a 4-3-1-2, where forwards Santi Mina and Iago Aspas take responsibilities of the opposition’s centre-backs, while Denis Suárez stays tight to the opposition’s single pivot. The three midfielders stretched across the third line of Celta’s structure starts narrow, preventing the opposition from penetrating centrally or accessing the half-spaces. The fullbacks and centre-backs also stay tight to their respective markers – following their marker deep and centrally should they move there.

Due to the narrow nature of Celta’s last two lines, the press is with the intention to force the opposition inside. As such, when the forward leaves the CB to pressurize the goalkeeper, he elects to cut off the lane to the opposition’s centre-back. This jump naturally frees space for the opposition in wide and deep areas – especially as Celta’s third line of pressure starts at such a deep height. Thus, the opposition’s fullbacks become pivotal in overcoming the pressure of Celta’s first lines. As the pass to the fullback starts to appear as a feasible option for the rival, Celta’s wide midfielder steps out of position to approach the fullback with the intention to keep the ball from breaking out of the nearest touchline. This jump is correlated with the shift of the rest of Celta’s third line – Tapia and the opposite midfielder close the space centrally on the side of the ball and stay tight to the opposition’s midfielders.

Thus, the jump of Celta’s third line leaves a lot of space between themselves and Celta’s defensive line of pressure. As a result, Celta’s last line is tasked with 1v1s that, if the opposition position their forward line adequately, occur in an ample amount of space. In addition to the large amount of space generated from the jump of Celta’s third line, the forward momentum from said third line inhibits Celta’s midfield from collapsing onto the opposition’s forward after he receives.

As in every out of possession set up, there is an indefensible space that presents itself. This pressing scheme opens up a vulnerability that the opposition can exploit: optimizing the space between Celta’s defensive and midfield lines.

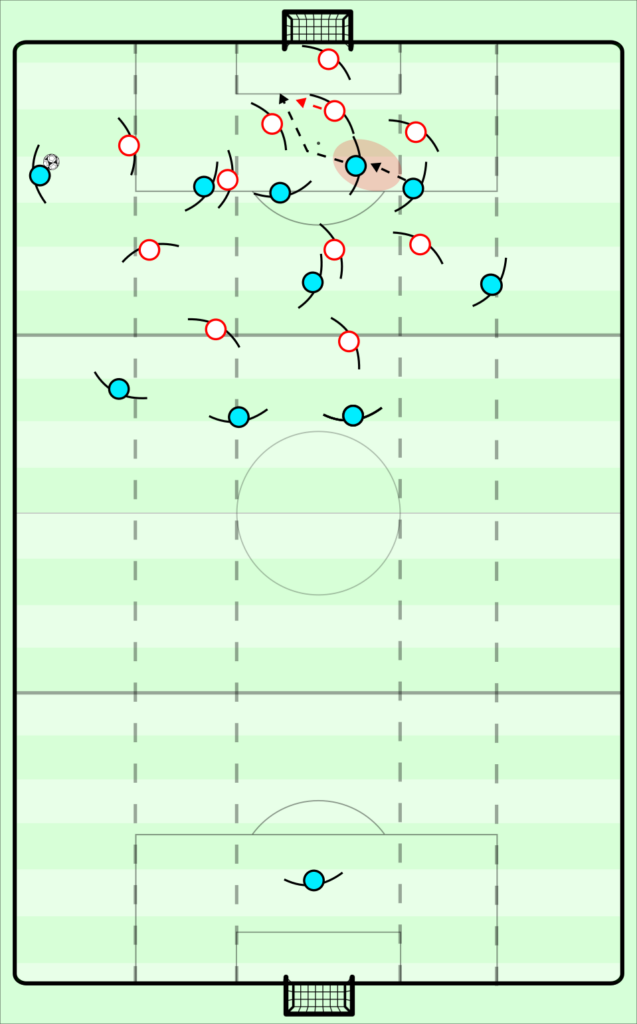

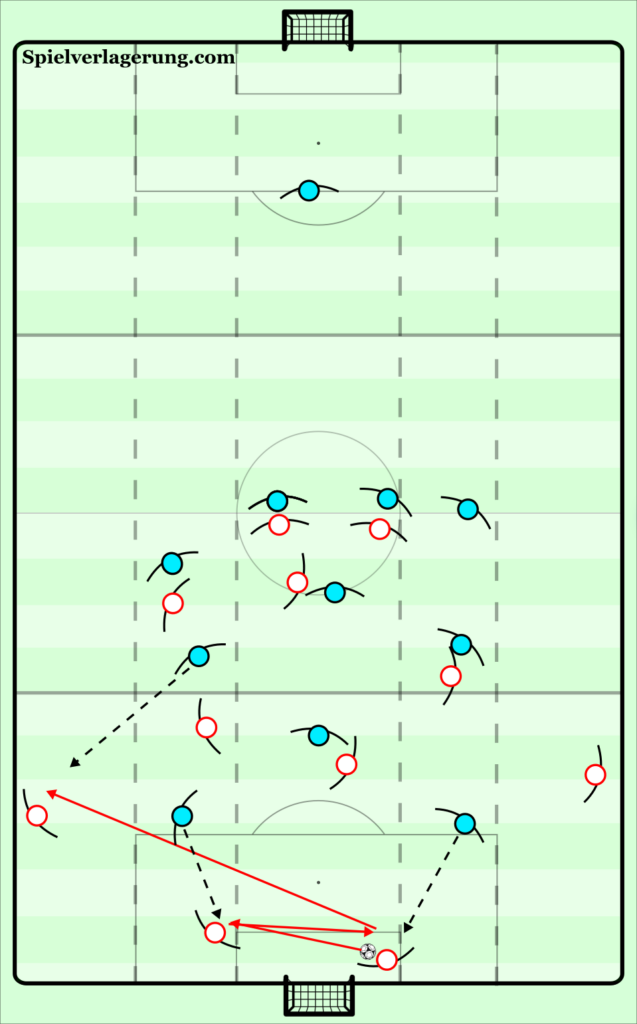

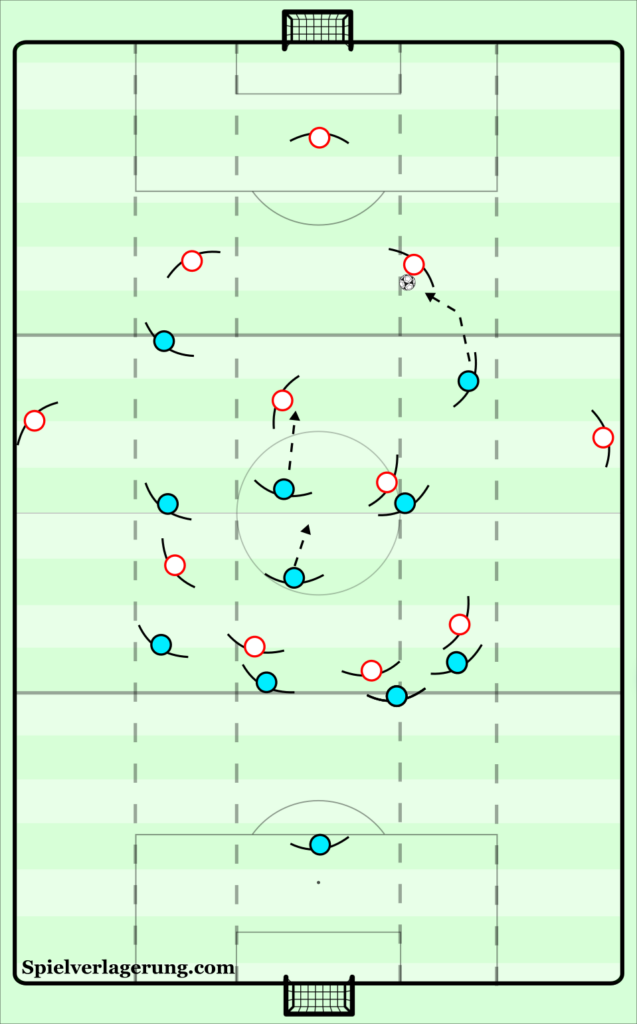

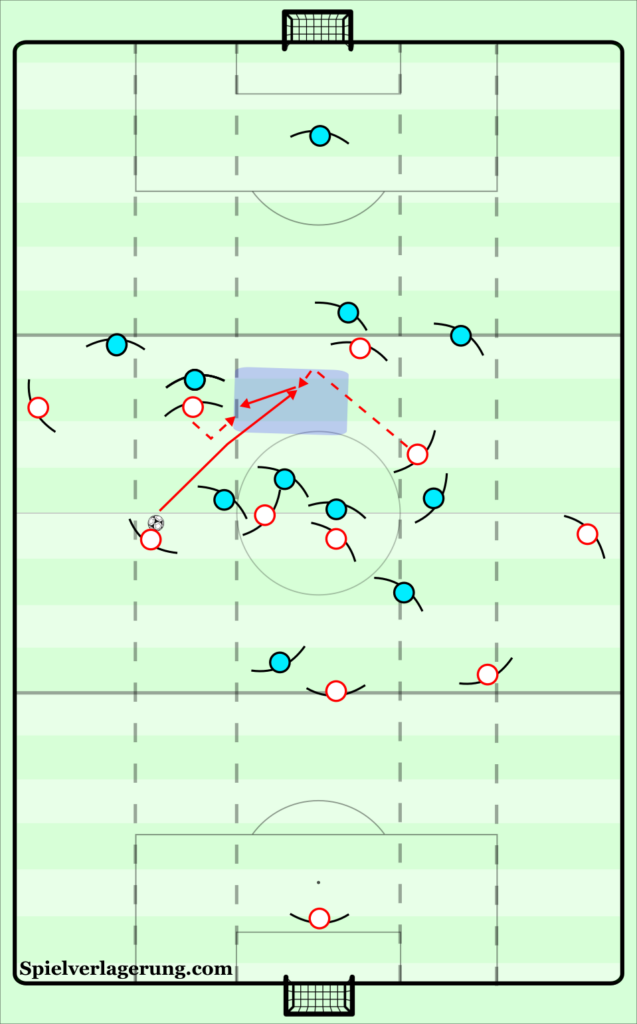

As a team who is in possession of the ball always has the initial numerical superiority (the opposition only has ten outfield players compared to the eleven of the team who is in possession), the advantage starts with the goalkeeper. This principle is critical in dismantling Celta’s high press. In order to overcome Celta’s high pressure, the opposition team could set up in a 2-3-2-1-3 shape from goal kicks, as shown in the images below. The goalkeeper and a centre-back should engage the initial pressure of Celta’s forwards with a bounce pass between one another. This engagement will further isolate the fullback, who will be positioned deep in order to maximize the distance that Celta’s wide-midfielder is forced to travel, generating not only more time for the fullback after receiving (a larger distance between Celta’s wide-midfielder and the fullback equates to a greater time that it takes for the Celta wide-midfielder to arrive to pressure the fullback), but also a larger space between Celta’s third and fourth line.

The deep, yet staggered, positioning of the interiors will occupy the necessary zones in order to arrive into this enlarged space. The ball-side interior should offer himself as an immediate central passing option at a withdrawn height. This would obligate Tapia to vacate a larger distance, thus expanding even more space between the third and fourth lines of Celta. With Tapia forced to step up the pitch to mark the deep interior, the advanced midfielder between the lines becomes the free man. In order to maintain the advantage in this threatening position, the forwards must position themselves in an adequate manner in order to pin Celta’s last line back. The occupation of the channel and the opposition’s ball-side centre-back is crucial to preventing a step up from Celta’s last line. Not only do these positions pin, but they also permit the forwards to receive a direct pass to overcome Celta’s midfield pressure. Upon reception of this direct pass, the forwards can set the free man between the lines.

When Celta defends in their own half, they set up in a 4-1-3-2 mid-block. Tapia marshalls the space in between Celta’s first and third lines; however, when Denis is forced to jump to the opposition’s pivot, Tapia steps in between the two wide-midfielders: essentially creating a 4-3-1-2. The space that Tapia’s jump leaves is usually minorly reduced by the backline, who step forward in unison with the jump of Tapia. Due to the narrow nature of the wide-midfielders, Celta’s midfield is heavily congested. Therefore, Celta intend to force the opposition into the centre of the pitch – which is achieved through the angle at which the forward jumps to the centre-back: he cuts the passing lane to the fullback, thus preventing immediate circulation to the wide spaces. This, in theory, demands that the opposition connects through the centre of the pitch before arriving into the indefensible space out wide. With this in mind, Celta’s block remains touch-tight in the centre of the pitch.

Should the opposition arrive into the wide-space – beit through connecting through the centre or through bypassing Celta’s forward’s pressure – Celta’s wide-midfielder steps to apply pressure to the ball. This jump is in unison with the shift of Celta’s block, which intends to reduce the space present around the ball. The ballside fullback of Celta then becomes man orientated: if his marker moves into the half-space, the fullback will track him. If the marker is on the touchline, the fullback stays tight to him on the touchline. This encourages the opposition, once again, to connect centrally into where they are numerical inferior. However, depending on the distance the wide-midfielder must travel in order to arrive at the ball in the wide space, Celta’s block may be forced to drop in order to protect the space behind their last line – thus losing pitch territory.

In order to surpass the first lines of Celta’s pressure, the opposition could form a 3+1 base structure. The presence of the single pivot will inhibit the ability of Celta’s forwards to remain wide enough in order to adequately cover the three centre-backs. As such, Celta will be forced to jump Denis Suárez to the pivot – and thus Tapia to the next midfield line, eliminating his presence between the lines.

Despite these jumps from Celta, the opposition will still have the initial superiority around the ball (4v3). As a result, Celta’s two forwards will be forced to decide which of the opposition’s centre-backs to leave free: an outside centre-back, freeing space for him to commit should he receive, or the central centre-back, providing him time (space) at the centre of the pitch. If Celta elect to leave the wide centre-back open, this initial superiority can be transferred up the pitch with the presence of two interiors and a single pivot, who will provide options for the central centre-back to overcome the pressure of Celta’s forward through a third man combination – the third man being the wide, free centre-back. The free centre-back should be instructed to make the progressive movement forward as soon as it becomes predictable that he could receive from a midfielder. This would permit the centre-back to surpass the first two lines of Celta’s pressure. As the centre-back travels forward with the ball at his feet, an opposition midfielder will be forced to close him down – thus transferring the initial superiority into the space that Tapia vacated when jumping in order to fill Denis’ place in the third line.

As shown in the image below, the space vacated by Tapia can be optimized through interchanges of height between the midfielders and forwards: as the ballside interior arrives deep to set the ball to the free outside centre-back, the near side forward can lower his height – dragging out Celta’s centre-back. The opposite interior could then move higher and centrally, escaping the mark of his midfield counterpart (becoming the free man) and moving out of the covershadow of Tapia. The pass from the committing centre-back can then be delivered into the feet of the opposite interior, who could then set to the withdrawn forward, or, if orientated properly, turn and drive at Celta’s last line.

Conclusion

Despite European places proving to have been unattainable for Celta Vigo this season, Eduardo Coudet has implemented fascinating tactical foundations that will excite many of Celta’s fans ahead of the next seasons. There are many areas that will need to be improved upon in order to carry out exactly what Coudet desires: specifically the quality in decision making from those within the first lines of the pitch for Celta in order to ensure a more efficient transfer of the initial superiority to higher areas. However, if fully backed, Coudet has the potential to make Celta into a powerhouse of not only Spanish football, but also European.

Written by Ryan Lamping

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Brian August 7, 2021 um 1:06 pm

It’s funny how people do say that the most dangerous place to be is the Middle of the road. Most of the articles in this site including this one explain in detail how to break a Mid-block with ease. We cannot all make it to the big leagues but these perspectives by far do a great job in helping us revolutionize our thinking and become quality players and coaches; better people in general.