How good (or bad) is Borussia Dortmund’s build-up?

Borussia Dortmund are in a tough spot. The German powerhouse have established themselves among the best teams in Europe and even more so in the Bundesliga where there is a considerable gap between Dortmund, Bayern Munich, RB Leipzig and the rest of the pack. Dortmund are expected to command the action on the pitch, and they themselves like to be in command.

Lucien Favre is certainly one of those managers that believe in possession and flawless passing as a way to dominate and drain the energy out of opponents. While flawless passing with infrequent shooting can seem dull to some, it is a technique to move opponents around and wait until there is the opening needed to advance quickly down the field. After all, Dortmund are at their strongest when the attacking cohort around Erling Haaland is moving at a rapid pace in open space.

The result from this is that Dortmund’s build-up play might be the most pivotal part of their game. BVB have, on average, 111 possessions per 90 minutes. However, as opposed to many other teams, a single possession usually consists of several build-up attempts, in particular because of Favre demanding from players to abandon an attacking play and start all over again from the back rather than desperately trying to force a shot with little to no chance of success.

“Of course my wish is that we can play through our entire team, starting from the goalkeeper, finding intelligent ways to get to the goal.”

(Lucien Favre)

What are the key components of Dortmund’s build-up?

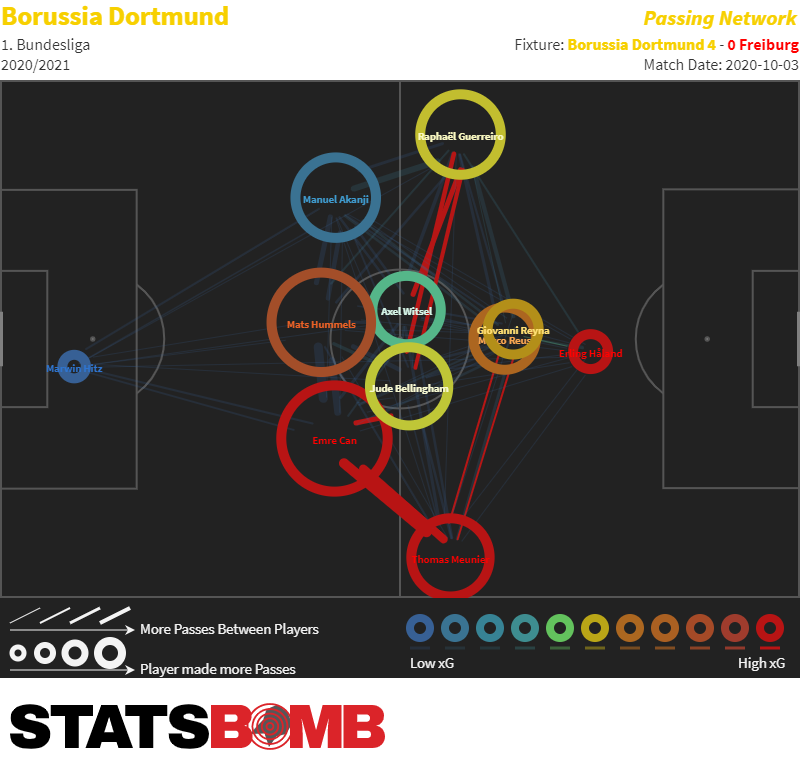

After tinkering with tactical line-ups involving a back four during pre-season, Favre decided to stick to the back three he successfully used for major parts of last season. He made slight adjustments to the structure in front of the back line, most notably the implementation of a mobile no. 10 in Gio Reyna, though the young American has also been used as a no. 10-winger hybrid when Favre went back to last season’s 3-4-2-1 in Dortmund’s recent encounter with Hoffenheim. That being said, the build-up structure has not changed. The only significant personnel change, as Thomas Meunier has replaced Achraf Hakimi, has had an impact on the forcefulness of Dortmund’s attack but less so on the early stages of the build-up.

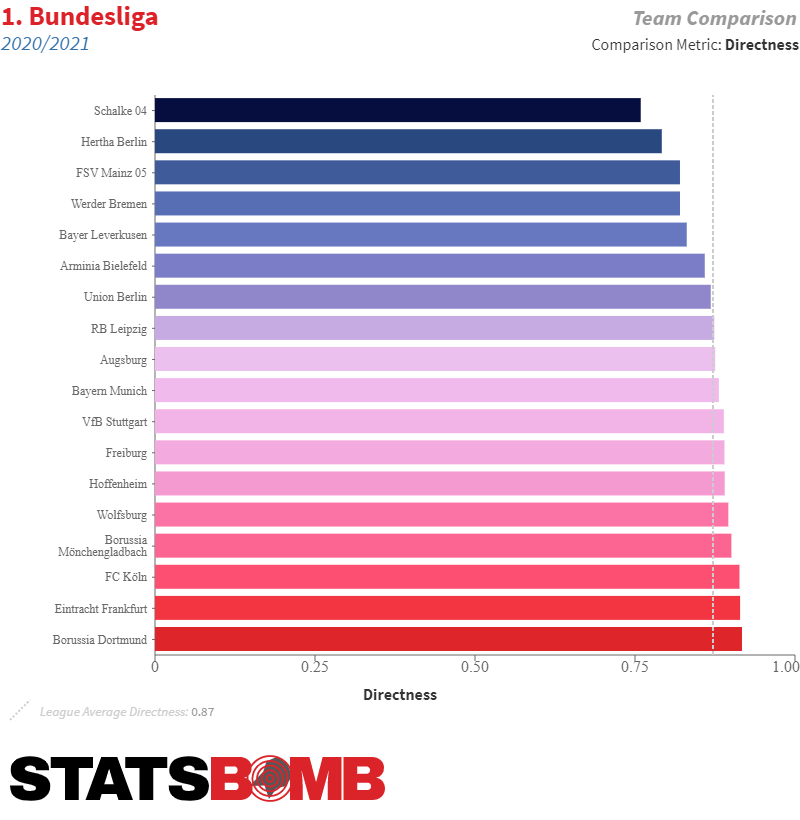

That build-up is usually done with a certain degree of urgency, particularly when Dortmund’s three defenders are pressured by a clear-cut man-marking scheme as seen in BVB’s match against SC Freiburg. The three defenders then attempt to move the ball laterally as quickly as possible, hoping that the opposing pressing line cannot keep up and offer openings that will allow Dortmund to bring the ball into the central midfield – which is the central component of the entire build-up. Dortmund always attempt to move the ball downfield through the middle of the field. While it might seem at times that Dortmund’s formation is stretched and the plays go to the outside, the main objective of the early build-up is to make use of Axel Witsel, Jude Bellingham and Gio Reyna, meaning to give them touches behind the first and occasionally second pressing line.

The rapid speed at which the three central defenders try to move the ball laterally leads quite naturally to passes towards the touchline, as it would, otherwise, be impossible to keep the ball going within the limited amount of space the back three occupies. This results in the two wing-backs being involved in the early phase of the build-up. Unfortunately, Meunier has not fully adapted to that aspect of the build-up, as he likes to advance quite quickly, but then finds himself in no-man’s-land up the field, as the right-sided centre-back is desperately trying to play the ball to the outside. Meunier then has to rush back and receive the pass, though in a position that lets him face Dortmund’s goal and more or less forces him to play the ball backwards immediately. The left wing-back usually sits deeper and thus is positioned with a better body posture that allows him to play into the midfield centre after receiving a pass from the back three.

This brings us to another key component of Dortmund’s build-up – diagonality, is created differently by the individual build-up players. First, there is Emre Can as the right-sided centre-back who likes to advance through the half-space, often moving slightly diagonally to break through flat pressing lines which don’t have the angle to close the gaps quickly enough. Statistically, Can is among the top 5 Bundesliga players in ‘progressive carrying distance’. Second, there is Manuel Akanji who plays as a right-footer on the left side and naturally tends to play diagonal passes into the midfield.

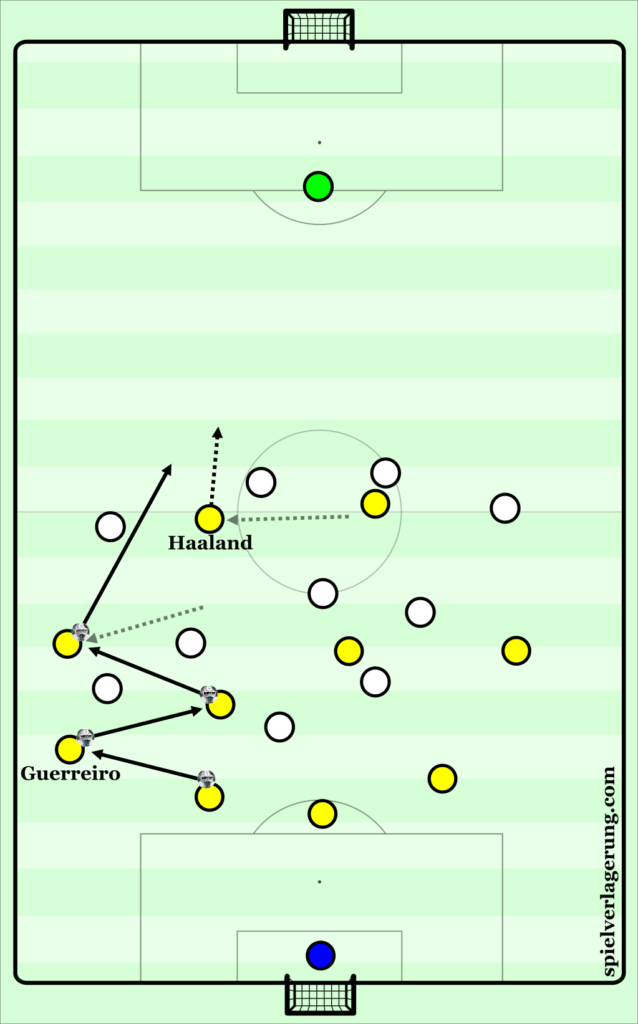

Third, there is Raphael Guerreiro who, as the left wing-back, often sits deeper to get a clear look at the field before playing the ball with his left foot either down the line or into the middle. Fourth, there is Felix Passlack who can quite effortlessly adapt his game and play as a left wing-back despite the right foot being his stronger one. Passlack knows that he has to turn his body towards the centre before receiving a pass from one of the central defenders in order to use his right foot and directly play a slightly curved pass into the middle.

While Passlack has done well in becoming a valuable part of Dortmund’s build-up, Guerreiro rightfully remains a linchpin of this phase in the game. Because of his proximity to the touchline, mixed with his deep position, he can play the inside pass at a sharp angle to Bellingham or Witsel who then follow up with a direct pass at a similar angle back to the wing. That pass is often ensued by a pass towards Haaland who is able to use the way Dortmund gain room through this sort of triangle on the left side to create separation from his defenders and make a run behind the last line.

Contributing factors

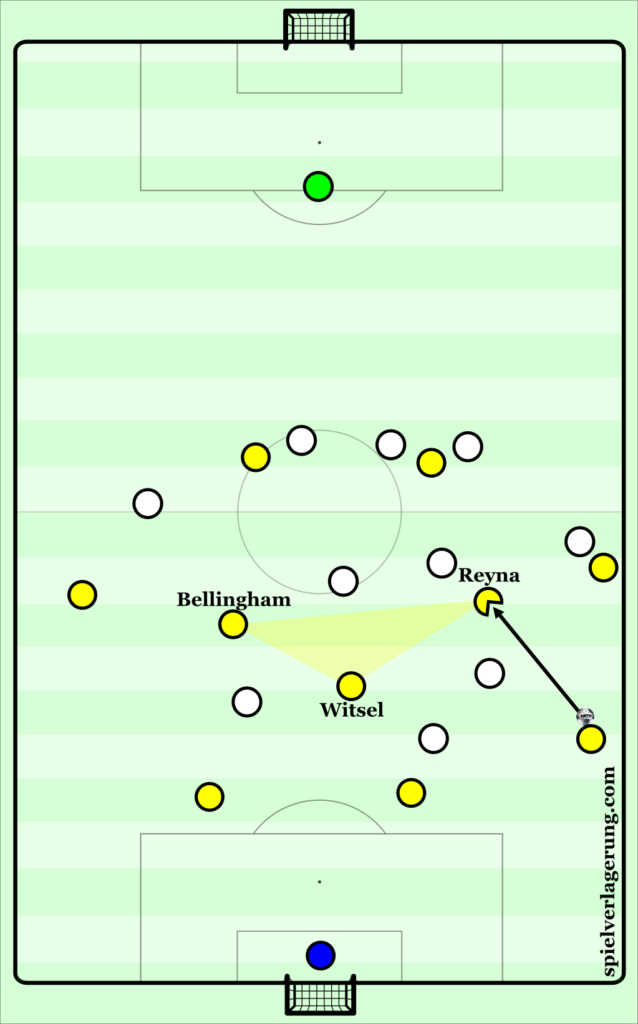

Many opponents think they have to meet Dortmund’s build-up with a high press coupled with a man-marking scheme that at least assigns markers to Mats Hummels and Emre Can. If these markers confront Dortmund’s defenders intensely, forcing them to quickly decide whether lateral ball movements are safe enough, BVB often switch to direct vertical passing. Even if a pressing player stands directly in front of Can, the Dortmund player can still find a way to pass the ball around the opponent at a slight angle, moving it vertically down the field. In that regard, Gio Reyna plays a crucial role, as he is usually the attacking player that makes the most lateral runs 20 or so yards down the field and can establish a position in a vertical channel linked to the right-sided or left-sided centre-back. Reyna’s mobility and relentless style of constant movement are key to breaking high presses.

What Reyna is to Can is Bellingham to Hummels, as the young Brit also likes to create separation from his marker and position himself in the channel in front of one of the centre-backs. His teammates already trust Bellingham to such a degree that they even target him as a receiver when he is in a crowded spot in the middle third. In recent years, Dortmund were lacking the kind of box-to-box midfielder that can thrive next to Witsel. At the age of 17, Bellingham has clearly shown an aptitude for progressive passing during the short time at the club and already appears to be a self-assured ball carrier that may not crack under the unique pressure most Bundesliga teams put on centre-midfielders.

Bellingham often uses the left half-space to call for a vertical pass, as he usually is higher up the pitch than Witsel. With Reyna tending to drop back through the right half-space, the two 17-year-olds effectively form a temporary no. 8 pairing in Dortmund’s build-up, creating a triangle with Witsel who has devoted himself to covering the backs of these two youngsters. That midfield triangle is usually narrower than the back three which, again, creates diagonality when a forward pass is played.

Another element that might not be a central component of the build-up, but makes Dortmund more unpredictable are Mats Hummels’s short dribbles where makes a few explosive steps from his initial position and gets past an opponent. Hummels quite regularly makes these short dribbles after receiving the ball from the left side to his right foot, immediately pushing the ball with the outside of the boot towards the centre and then following up with a few more touches in an attempt to win some spaces and provoke the opposing team to react. Hummels’s short dribbles can, at best, create a domino effect and free at least one midfielder from his marker.

The descriptions above have been made – and possibly read – under the assumption that Dortmund intend to keep passes short and the ball on the ground. It is certainly true that Favre likes ‘small ball’ much more than a style with long passes which are less controllable and usually create a considerable amount of chaos. That said, Dortmund are quite adept in sparingly employing long balls. These are most effective after Dortmund have advanced and decided to play the ball back to the defenders who immediately go for a long diagonal ball to a player on the far side or an attacker making a run behind the offside line. In that scenario, Dortmund smartly exploit the momentum of the opposing defence.

Pitfalls

There are certainly a few pitfalls that could endanger Dortmund’s success in the early phase of their build-up. Recent performances against Augsburg and Lazio have made that crystal clear.

Emre Can and his half-space runs are rightfully praised as a tool to break pressing lines, as such runs are commonly effective against most defences. However, Can tends to be a bit reckless with his forward movement, likely channelling his inner midfielder who wouldn’t face severe consequence in case of a turnover. Playing at the back means that he has to decrease the risks he takes when he attempts to disturb pressing structures. The fact that he makes so many progressive runs successfully can be seen as a positive, but knowing Favre and how calculated—or some could say risk-averse—he is, it is hard to believe that the Swiss doesn’t raise an eyebrow when Can decides it is time to take on two or three defenders.

The reason Can’s progressive runs usually work is that he can exploit vast chunks of space between opposing pressing lines. Most opponents believe they have to attack Dortmund early and intensely, not giving them any time in the first phase of the build-up. They fear that a competent passer like Hummels could catch them with his accurate vertical balls or hit a perfect pass over the top of the back line as he has done so many times in the past. But those teams that sit back a bit are usually more successful against BVB.

Hoffenheim, for instance, did not apply a high press in their recent match against Dortmund and instead created density in the middle third. Similarly, Lazio did not constantly use a high press, as they invited BVB to move a bit and then brought Dortmund to a halt, as the Italians intended to force backwards passes and passes to deep-sitting wing-backs. These passes by Dortmund were used as triggers by Lazio who quickly advanced and closed down passing options close to Dortmund’s ball carrier.

Dortmund’s build-up players usually take the bait and move a couple of yards forward, making the pitch more narrow and thus destroying space that could otherwise be used for medium-range passes to Bellingham, Witsel or Reyna. Once Hummels and his teammates are at the halfway line, any kind of vertical pass to one of the midfielders is usually short and somewhat slow, because a forceful pass would only increase the risk of an unclean touch by the receiver. But the shortness of the pass and the density don’t allow the receiver to make a quick and safe 180-degree turn towards the penalty area.

Another factor that could harm Dortmund’s build-up are injuries. Favre has been forced to change the line-up of his back three quite frequently in recent weeks. Thomas Delaney being slotted into the role of the left-sided centre-back against Hoffenheim and Lazio was nothing more than an emergency decision by the Swiss coach, although Delaney did quite well in this unfamiliar role. Still, an established line-up with Hummels, Can and possibly a fully fit Dan-Axel Zagadou would help Favre to hone the positional play and improve the accuracy and effectiveness of passing chains.

While there is certainly enough room for improvement, as shown by Dortmund’s disappointing performance against the pressing experts of FC Augsburg and the astute defenders of Lazio, BVB’s build-up provides a decent base for the attacks by the Black and Yellows. After all, there is no doubt that Jadon Sancho, Marco Reus and Erling Haaland are one of the most talented attacking trios in Europe. That Dortmund get the ball to them is what matters.

The article was first published here as part of a collab between StatsBomb and Spielverlagerung.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Brian December 18, 2020 um 8:12 am

For the team lead by R. Maric I wish you all the best when and if you do start working with the Dortmund team. Just don’t forget us loyal fans/supporters of this website… Provide a review of the process and progress made in M’ Gladbach and all your tactics

O Barbosa November 7, 2020 um 1:22 pm

Coach from Brasil here. Love and read all the post of this amazing work