Chelsea Struggle to Opening Win over Brighton

After one whole year of ‘commitment’ to ‘project youth’, Frank Lampard signed off on approximately £200,000,000 of footballers to revamp his side’s core. How he plans on moulding these players into a coherent system is certainly one of the main challenges he’ll address this season. If he achieves to solve such a dilemma – if you could call it that – the West London outfit could very well be a third side to challenge at the very top of the table.

Another team going into their second season under their manager – Graham Potter’s Brighton proved to be a quietly-intriguing outfit last year. The Seagulls showed plenty of promise and although their final position was not too dissimilar to their placing under Chris Houghton, the development on the pitch itself was clear. Going into the new season, Brighton have added some quality players in Joël Veltman and Adam Lallana while Ben White returned from his impressive loan spell at Leeds. Following Project Restart, explosive wing-back Tariq Lamptey proved to be another exciting member of their squad. Despite relatively low amounts of money spent, Potter’s side will be one that I’ll watch attentively in how they continue to progress this year.

Therefore, the opening match-up between these two teams posed to be an interesting one. Although we wouldn’t get definitive answers to larger questions surrounding either team, we potentially got a slight insight into how both coaches will approach their seasons.

Chelsea opt for a 4-2-4

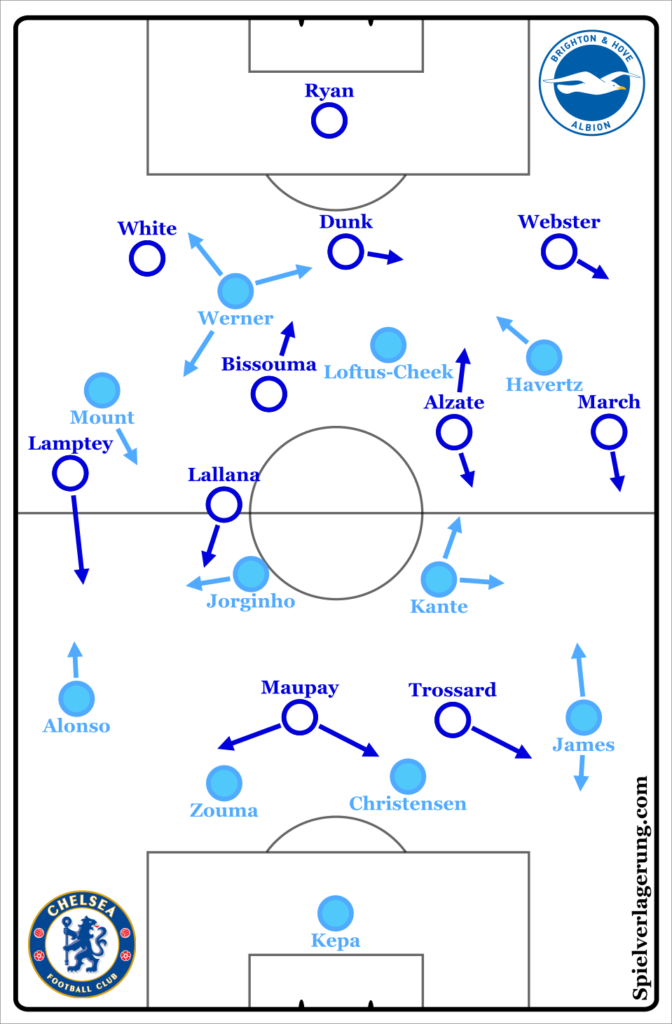

Lampard aligned his team in a 4-2-4 with the ball with an interesting placement of attackers. Timo Werner and Ruben Loftus-Cheek started centrally while the nominal ‘wingers’ were Mason Mount on the left and Kai Havertz right. On paper, this gave them a front four against Brighton’s back five with two central midfielders against a defending midfield three. Naturally, as is often the case against a 5-3-2 defensive block, this left the full-backs as the free players.

Given how often this is the ‘dilemma’ space for a 5-3-2 – due to the lack of width in the ‘3’ and ‘2’ – one of Potter’s main considerations would have been how to approach the situations where Chelsea’s full-backs stayed deep to receive the ball. Their planning for this was clear, as the home side solved many of these moments well – especially on their left side. As Chelsea circulated across their first line, left wing-back Solly March would leave the defensive line rather early and position himself close to his opposing full-back. From this position, he could immediately attack Reece James if he were to receive the ball and thus Chelsea were discouraged from playing wide in the first place. On Brighton’s right against Alonso, Tariq Lamptey would instead stay deeper and – given the three vs two overload in midfield – Adam Lallana could step out to engage. Although this wasn’t as ‘preventative’ as the early engagement from Solly March, it still allowed them to have fairly sufficient access in these spaces, with their formation becoming essentially a 4-4-2 at times to match up Chelsea man-for-man.

This wasn’t an absolute solution to this situation, however. Chelsea could keep their ball-far winger very wide so that upon switching from left to right, March couldn’t step up due to the presence of Havertz on his outside.

The downside to this, of course, is that it’s not the optimal use of one of Germany’s biggest attacking talents. In a role that didn’t often have him acting as a passing option between lines, Havertz found it difficult to integrate himself into the match.

One of the main weaknesses with Brighton’s setup – with the left wing-back higher – is that it leaves the other four defenders playing man-for-man against Chelsea’s front four. Given the obvious quality of the forward options, defending without an additional player as cover could be a rather risky approach. Yet despite clear potential for the visitors to create dangerous moments from these situations, herein lied Lampard’s main issue from the game.

Unclear Division of Forward Roles

I initially planned on making this note in the conclusion but figured it’s more effective as a preface to this section. By no means do I believe that Chelsea’s attack should have a perfect understanding between one another. Simply – this was a clear issue for Chelsea in the game and I’ve analysed it as such, it’s not necessarily a complete reflection of the coach.

Chelsea’s fairly typical 4-2-4 structure was an expansive one. Four players on the highest line typically means you have high width and thus can stretch the opponents’ last line and create gaps between defenders. What it also means, however, is that your base structure often only has three layers of players. Consequently, the structure is very dependent on the timing of movements from the forwards so that different layers of passing options can be created at the right moment for the player on the ball.

As I have noted in previous analysis, you can classify off-the-ball movements into roughly two categories – to reduce oppositional cover or to receive. The two primary actions to reduce oppositional cover are:

Pinning – Movements (or positioning) to force defenders to stay in their position or move backwards to their own goal. An example would be a centre-forward running in-behind so that the centre-backs cannot step up to close down the space behind the midfield.

Luring – Movements (or positioning) to draw defenders towards the ball. The antithesis of ‘pinning’, an example would be a centre-forward coming short to draw the centre-back out, creating a gap for a teammate to run in-behind into.

Of course, a movement that is ‘pinning’ or ‘luring’ can also be a movement to receive a pass. Ultimately, it’s the threat of the player receiving a pass that forces the defender to adjust. If the opponent doesn’t look to prevent the moving player from being free, then of course the movement is one to receive. It’s when the defender adjusts to the movement that it becomes one to reduce oppositional cover.

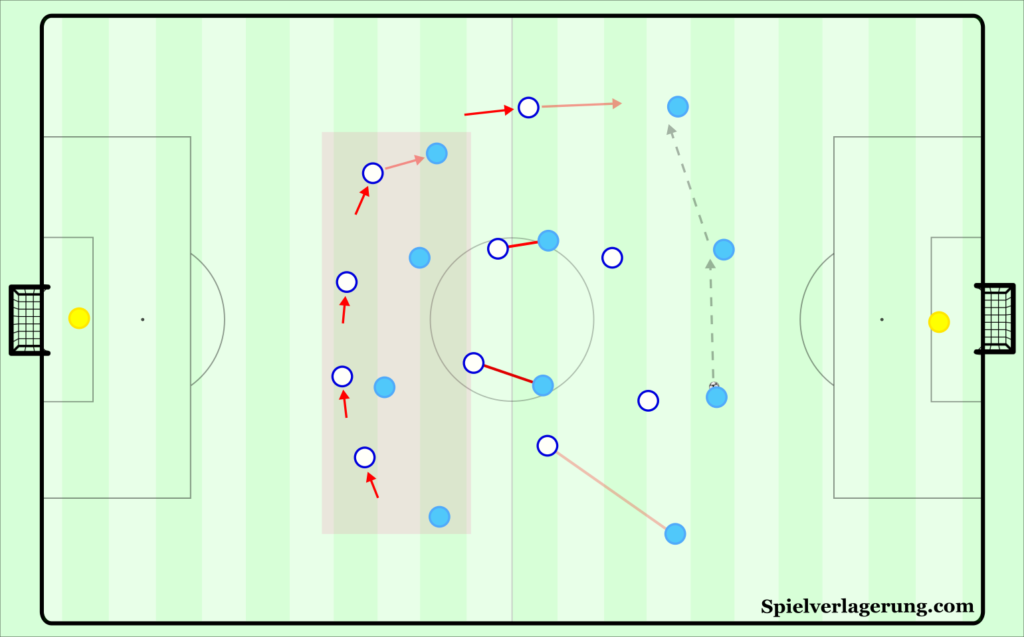

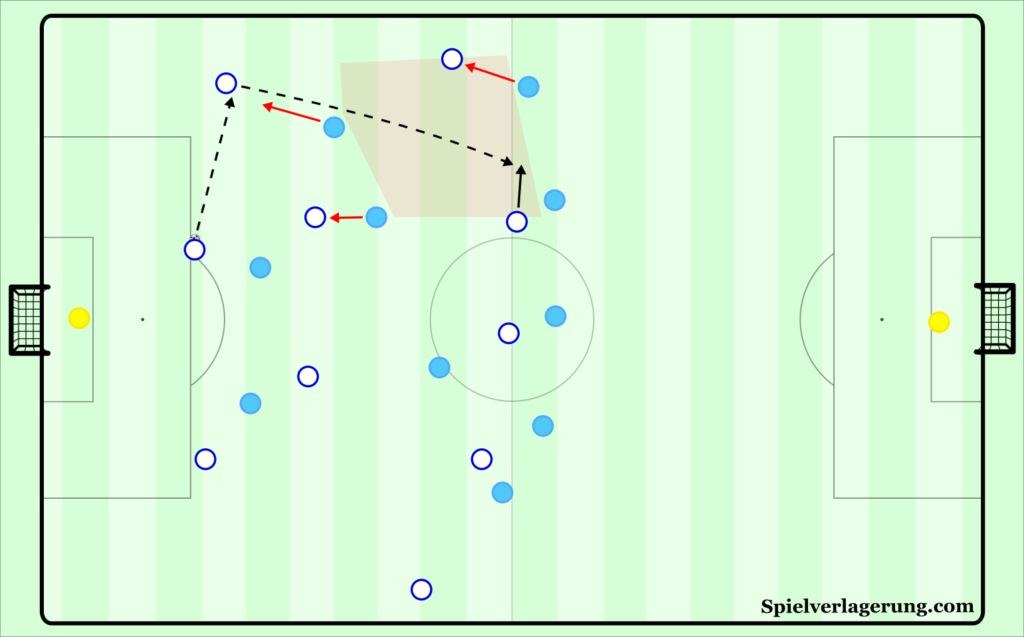

Chelsea’s issue here was that there seemed to be a rather unclear division of roles across the front four. None of the forwards coordinated their movements well between each other and would often show for the same pass. Particularly down their left side, Mason Mount and Timo Werner both frequently dropped short with then nobody making a movement in-behind. The same can be said centrally where, although Werner did make some dangerous movements in-behind, if the German were to drop short there would be no ‘counter movement’ by the other forwards to maintain a depth threat. On Chelsea’s right side, Havertz’ nearest teammate was often Loftus-Cheek who rarely looked to move in-behind. This complicated things for the German at times, who struggled without a teammate pinning his defender and thus often couldn’t receive in space. When the forwards did make counter-movements between them, the timing was often far off – for example with the dropping player moving too late to influence the positioning of the defender.

Of course, not only are the timing of these movements key to for movements in-behind, but also to reduce oppositional cover of a free player to ask between the lines – which was again an avenue which Chelsea failed to create. Given that Brighton’s pressing structure often resembled a 4-4-2 with Lallana moving wider to engage Alonso, spaces were certainly available between the lines to play through into. Yet due to a lack of coordination with the front four, their ability to occupy these spaces let them down. One of the few times they managed to exploit this space came fairly early in the first half, where Werner pinned Lamptey and White, enabling Mason Mount to come short and receive in space as Lallana had moved out early towards the touchline. The English ten immediately looked diagonally to play in-behind to Kai Havertz but the pass was just ahead of its target – however the danger of such spaces was made evident.

Due to the lack of coordinated movements from the front four and just two central midfielders, Chelsea’s full-backs often had very limited options to play forwards from their wide positions. With Brighton’s more proactive approach to defending these areas, they were able to still apply sufficient pressure on the full-backs and ultimately stifle Chelsea’s play with the ball.

Given Brighton’s success (or Chelsea’s failure) in their approach in the middle third, Potter’s side were able to force Chelsea back and press them within their own third. Again, there was a man-for-man situation in Brighton’s defensive line as March stepped up and Lampard’s side looked to play directly into their forwards to try and capitalise. It didn’t seem as though there were particular patterns behind the strategy, apart from targeting the height advantage against Tariq Lamptey or finding Loftus-Cheek and consequently they rarely posed a threat.

Instead, the visitors’ most dangerous moments almost entirely came in transition. Of course, the first goal itself was more or less self-inflicted by their opponents, but Lampard’s side looked threatening when counter-attacking from deep positions too. Havertz and Loftus-Cheek could drive with the ball while Werner was the primary threat in-behind against the last line.

What Could Chelsea have Done Differently?

In itself, Chelsea’s plan wasn’t that bad – if the movements amongst their front four were executed better, I’m sure they would have had more success with the ball. That doesn’t stop us from posing some ideas which could have fared better against Brighton’s setup.

More Suitable Integration of Havertz

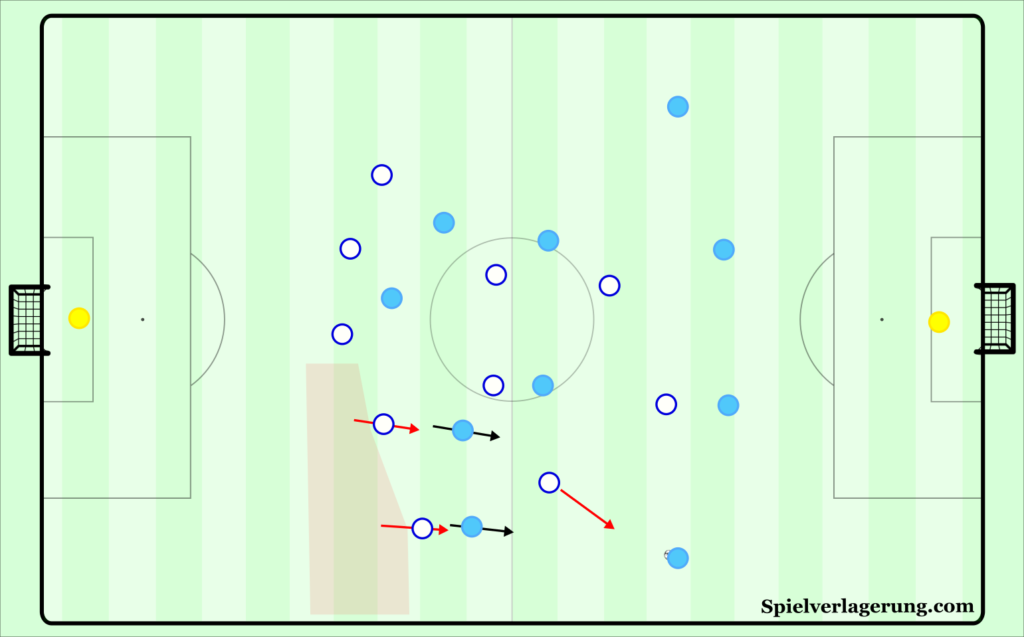

One of the main talking points from the game was the underwhelming performance of Kai Havertz, but his role certainly didn’t allow him to make the use of his talent. Often isolated in his position wide on the right, he mainly performed pinning actions and was rarely made a passing option. If he were to try and receive, the lack of a pinning teammate around him meant that he never really got free of his defender. Although there was still the need for a pinning player on the right to affect Brighton’s defenders, it could have been more promising for this role to be fulfilled by Reece James or Loftus-Cheek, allowing Havertz to play closer to the middle of the pitch and closer to Werner, who could have afforded him slightly more space to receive. Having Reece James would have potentially sacrificed a bit of stability in their build-up, so I’m leaning more towards RLC. Although he’s not the ideal player to be a pinning threat, he wouldn’t perform the role -that- much worse than Havertz and he hardly had a positive contribution in his central role.

Werner’s Positioning as a Depth-Option

When it comes to centre-forwards who are depth threats such as Timo Werner, I’ve often found that it’s more beneficial for them to play in a wider position as opposed to centrally. Although the forward played mainly on the left, I found him at times too central after Chelsea circulated the ball for a period of time. From a narrow position, any runs in-behind that he makes are going to be angled towards the touchlines – inherently less dangerous spaces if he were to receive since he’d need to dribble the ball back inside to be an immediate goal-threat. Instead, if a run is made diagonally inside from the half-space, then he’s typically receiving directly towards goal and the defence simply cannot recover.

This would have been less of an issue if Havertz was available as a central option to receive in space. Werner’s positioning as a pinning would have potentially allowed him to receive and Chelsea could have had an option in-behind (Werner) and between (Havertz), making them a bit more omnipotent. I don’t think there’s so much use in talking about entire structural changes, since it’s the first game and players are still to come into the team, but I feel that those two adjustments for their two best attacking options could have posed more issues for Brighton to face.

Brighton with the Ball – Asymmetrical Approach with Relative Success

Brighton, on the other hand, displayed a more coherent approach with the ball, but still had limited success in breaking down their opponent through a lack of players acting consistently as passing options in central areas.

As Potter’s side often did last season, they built-up with a lopsided first line where left centre-back Adam Webster moved wide, Lewis Dunk moved to the left of goalkeeper Matthew Ryan while Ben White stayed on the right side. Thus, Solly March moved into a higher position Lamptey stayed slightly deeper but still wide. In the centre, Bissouma was consistently the deepest midfielder with Alzate slightly higher on his left. New signing Adam Lallana played much higher on the right to essentially form a front three with Maupay and Trossard. This setup essentially formed a 3-4-3 or 4-2-3-1/4-2-2-2 with clear asymmetry between sides.

Brighton acted against a 4-2-2-2 press from Chelsea, whose front two aimed to control Brighton’s two situational centre-backs in addition to Bissouma. Their midfield was rather man-oriented with the two wingers primarily looking after Adam Webster and Tariq Lamptey, while the two midfielders closely followed Alzate and Lallana. Chelsea’s back four defended quite typically against Brighton’s front three.

Given the asymmetry of Brighton’s build-up between their left and right we can approach their differing strategies accordingly.

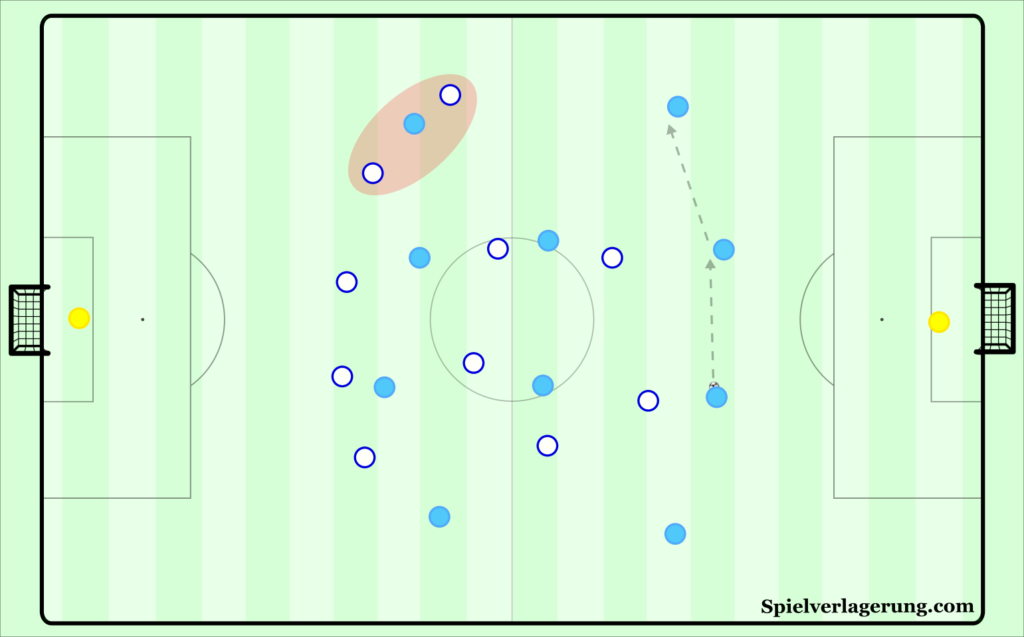

Left – Lure Havertz and Kanté to play directly into Front Two or via March

Down Brighton’s left, it seemed as though they wanted to use the deep and wide positioning of Adam Webster to draw Kai Havertz out while Bissouma’s deeper positioning had the same effect on N’Golo Kanté. Through doing so, they sought to increase the gap between Chelsea’s midfield and defensive line to create the opportunity to play directly into the last line and attack into open space. How they did this mainly depended on how Reece James defended Solly March.

If James pushed on early to defend March, Brighton would look to play directly into their two ball-near forwards. Since the defensive line had to shift as the right-back moved out from his position, the space for Maupay and Trossard to receive these direct passes was greater. Such situations were normally more dangerous for Potter’s side, as the larger gaps allowed them to play threatening channel balls to their dynamic front two. If March wasn’t approached immediately and could receive under relatively little pressure, then they could play into their wing-back. Upon receiving, he would soon face pressure and thus he would be quick to then play the ball diagonally inside, again into the front two.

After building up down their left, Tariq Lamptey posed a dangerous option to switch to on the right side as Chelsea shifted across to defend ball-near spaces. Upon receiving with space to drive into, the young full-back was very direct in taking on Alonso or looking to combine inside with Lallana. Of course, this was not only a good attacking option, but one to relieve pressure if Brighton got into a tight situation centrally.

Right – Pin Mount and Jorginho to Create Space for Bissouma or (in reality) Play Direct

Whereas Brighton looked to draw-out defenders through their left, they sought to pin-back Mount and Jorginho when building up through their right with the advanced positions of Lamptey and Lallana. Instead of creating a gap between Chelsea’s midfield and defence, they seemingly wanted to a gap between Chelsea’s front two and the rest of the midfield.

In theory, this would leave pivot Bissouma with more space in front of him to receive on the blind-side of Chelsea’s pressers. However, the front two and in particular Werner managed to apply pressure on the centre-backs while restricting Bissouma as an option quite well and it wasn’t a consistent way through for Brighton. Bissouma could have possibly moved a bit wider from his central position to move out of the cover shadow of Ben White’s presser. Because he rarely moved far from the centre of the pitch the midfielder was quite easily covered without Werner or Loftus-Cheek having to adjust their runs dramatically.

Without this option, Brighton ended up going quite direct from their right side. Given that it didn’t seem the main idea of their build-up like down their left, they weren’t well prepared to create space to attack from these long balls. The defensive line was rarely stretched, and the positioning of the forward players was quite static. Consequently, Chelsea were able to defend the situations quite comfortably and Brighton didn’t pose a threat from these moments. Brighton did have slightly more success through their right in the middle third, where Lamptey was able to receive behind Mount and drive into space or combine with Lallana. Such moments were more or less down to the excellent performance of the young full-back rather than anything notable tactically, though.

Lack of Varied Receiving Options

Brighton’s attack through both sides was hampered by the lack of (varied) passing options to accelerate the possession. Their structure was relatively effective in reducing oppositional cover of spaces higher up through provoking pressure or pinning defenders into deeper positions. However, they only consistently had direct passing options with their forwards either in the channel or into a duel. From structured build-up moments, it was very rare that an attacker would be free as a passing option in space.

Of course, it’s very much possible that they don’t seek to create these options to play through – Maupay and Trossard are more dangerous when receiving on the move and in depth and it’s generally a lower-risk strategy (despite them taking risks early in build-up). At the same time, it still harms them because they can become quite predictable once they break the first lines of pressure. This is something I have noted quite often about Brighton’s build-up against a high press, even though it wasn’t such a decisive issue in this game in particular.

When they entered the final third through these channel balls and the forwards managed to retain the ball Brighton did show promise. Potter’s side were particularly dangerous in combining inside into the box from their wing-backs and ball-near forwards or midfielders from deep. This was evident from both sides, but Lamptey and Lallana in particular were effective with the former Liverpool midfielder displaying his qualities in dynamic combinations while Lamptey’s directness caused problems all evening.

Considering their issues from structured build-up, perhaps it was for this reason that some of their most impressive attacks came from more unstructured possessions. On a number of occasions, they combined dynamically through midfield with positional rotations. Against quite a man-oriented midfield in Chelsea with only two central midfielders, Potter’s side were able to create sizable gaps in the centre into which they could play from outside to inside. Unfortunately, due to the rotations, this sometimes meant that the player to receive in space wasn’t ideal, such as a centre-back, so some moments were wasted.

Conclusion

There weren’t many tactical developments across the second half, aside from typical effects of game-state. The flow of the match came a bit variable as Brighton looked to press Chelsea backwards and regain possession to transition from their long balls, while Lampard’s side tried to find stability through circulating to their full-backs in the middle third. Going behind via a long-distance effort immediately after finding an equaliser, Brighton weren’t deterred in their attempts to bounce back and had two good chances before conceding the third goal. Following the 3-1 however, they struggled to create another chance despite having a fair amount of possession in the final third.

The match certainly wasn’t of the highest quality, but we did see a glimpse into the prospects for both teams this season. For Brighton, it will be interesting to see if and how Potter develops his side to have a more varied threat with the ball as a potential next step after a good first season. For Chelsea, how Lampard manages to fit his array of new talent into a functional system is question #1, #2 and #3. This opening match didn’t show much promise in that light, however one would expect this to be a key early development for the first quarter of the season.

4 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

MSP September 18, 2020 um 9:22 am

Seems to me that Lampard is more tactically sound than he is given credit for, their main problems against brighton were the execution of said tactics and the lack of “chemistry” among the front four.

Excited to see what he can do with this Chelsea side, plus I’d also like an article on how you go about analyzing games, would be very interesting.

Stef September 17, 2020 um 7:57 am

Great analysis, thanks! Seems like Lampard is in fact a talent – but now needs to turn his 200m threads into a successful fabric. Excited for this season…

Sikander September 16, 2020 um 6:58 pm

Please can you tell us how you analyse a football match? I have my own way, but I would really find it useful if one of your team members published an article on the subject

Thomas Booth September 17, 2020 um 3:54 pm

Yes! I agree, that would make a great article. I’m always fascinated how others analyse matches, i would love to know what you are looking for when watching a game