The Art of the Long Ball

Ever since the massive success of Guardiola at Barcelona, a lot of people have gravitated towards the philosophy of positional play. This momentum in turn, increased the number of articles and analysis on the subject, putting a large emphasis on playing out from the back in the current literature on the game. Because of this, I thought that it might be interesting to go completely against the grain, and instead focus on long balls and how one is able to utilize them.

“One must shed the bad taste of wanting to agree with many” ~ Friedrich Nietzsche

Within this article I want to focus on three different long ball situations, long balls from set-pieces, chosen long balls and forced long balls. In my opinion, every long ball falls in either one of these categories. While the specifics of each category result in particular second ball situations. Furthermore, I want to address counterpressing second balls, backwards pressing on second balls, and positional superiority on long balls.

Long balls are mostly used in situations in which teams are trying to build-out from the back. In contrast to a short (patient) build-up, long balls are a much more direct approach. Instead of creating an advantage in each line before progressing to the next, the ball is immediately played far-up the field with teams trying to create the advantage there. On the one hand, this allows for a quicker vertical progressing, the ball goes immediately from the goalkeeper or defender to one of the forwards, on the other hand it’s much less controlled compared to a short build up. As it’s a high ball it’s difficult to control for the receiver, while the time the ball spends in the air also gives the defenders time to position themselves to defend the pass.

As the ball is high and travels quite a distance, the player who receives the initial long ball is (usually) not able to control the pass and continue the attack, unless the ball is played into an open space, therefore winning the initial header is not enough to attack from a long ball. This is where the notorious ‘second ball’ comes into play. After the initial pass, players need to be positioned in such a way that allows them to win the second ball in order to continue the play.

Generally speaking, there are two main categories of second balls. In the first situation the ball is played backwards (towards the own goal) for players behind the player heading the ball to win the second ball. The second situation is the player heading the initial ball forwards (towards the opposition’s goal) which allows players to make runs in behind.

The second category is the more direct approach, it allows a team to immediately create a goalscoring chance from the long ball. However, it’s also much more difficult to execute. Not only does the initial header have to be won and headed into the preferred direction, when the ball is just slightly overhit the opposition’s goalkeeper is able to intercept the ball before any chance can be created. Which might explain why this kind of pattern isn’t seen much at the highest level.

The first category is the more controlled approach, by positioning your second ball structure behind the player who’s contesting the initial header you have a more solid base for winning the second ball. Even if the header isn’t perfect, the defender wins it, or neither player gets a clean header, you have good platforms to win the second ball and continue the play. While it also gives you better counterpressing opportunities when the opposition win the second ball.

Using this kind of long ball pattern can have one of multiple aims. First of all, you can try to have the player winning the second ball receive the ball under control. This allows him to either continue the play forward, or retain possession for his team. The second aim is to gain space or to get out under pressure. By playing long you don’t give the oppositions the chance to press you near your own goal, while it does allow you to take the pressure to the opponent’s half and push them back.

The three different types of Long Balls

Dead Ball

The first of the three long ball situations I distinguish is a ‘dead ball’ situation. Dead ball situations consist of goal-kicks and free-kicks that are taken deep in the own half. I coined these situations ‘dead’ balls as the player playing the long ball can’t be pressed, and the game is ‘dead’ for a couple of seconds. This type of pass can suit both aims of the long ball, depending on where the ball is aimed to and how the rest-defence is structured. Balls played through the centre with good positioning for the second ball are usually favorable for winning the second ball and progress from there. While balls to the side are usually favorable for gaining space.

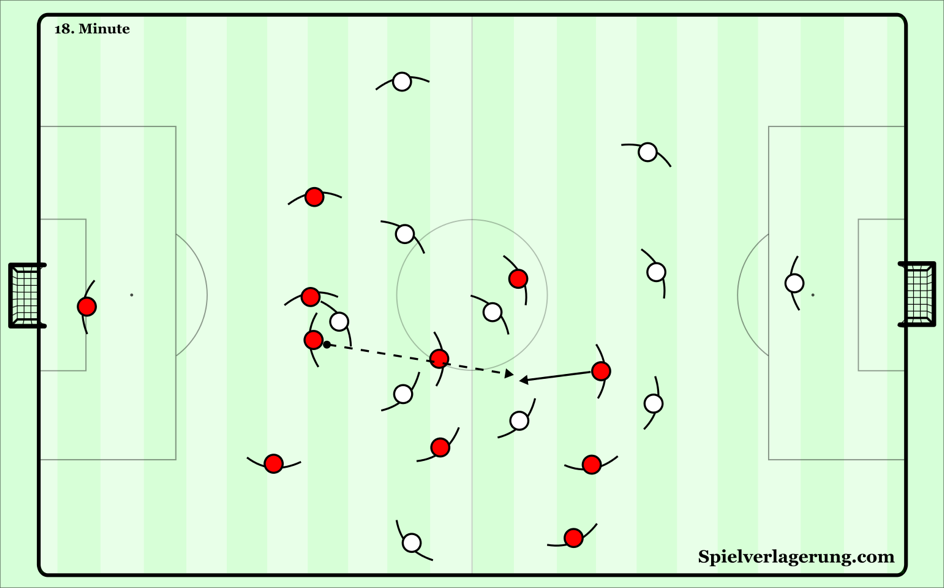

There is a quite a distinction between winning a second ball in a compact situation, which is the case here, and winning the second ball in a big open space, which can be the case in the next sections. When playing long from a ‘dead ball’ you have full control over the positioning of your players, after all it takes some time before the ball is taken and the player taking the ball can’t be pressed by an opposition player. As the player taking the ball can’t be pressed the pass is usually much more accurate compared to a long ball from open play. While your second ball structure is much more organized and layered as all the players were able to get into a pre-determined shape. ‘Dead’ balls, including set-pieces, can be trained on the training ground due to the unpressed nature of the passer. While long balls from open play create a much more chaotic and random situation that can’t be replicated exactly on the training ground.

In a compact situation you will usually have quite a lot of players near each other, which usually results in multiple consecutive duels for the second ball, with neither team being able to really control the ball until it is played out of the pressure zone. In this type of situation organized counterpressing on second balls is quite common, resulting from the organized structure the teams are able to get into.

In more open situations, the player playing the long ball is often pressed which puts limits on the accuracy of the pass. In addition, the spaces are usually much bigger, therefore there’s usually only one or two duels for the second ball. Winning that duel allows space for the winning player and allows him to continue the play

The main disadvantage of compact situations is the fact that your opponent is also able to get into a pre-determined shape. They can see at whom you want to aim the ball and can adjust to that. While the ‘open-ball’ situations can be just as chaotic for them as they are for you.

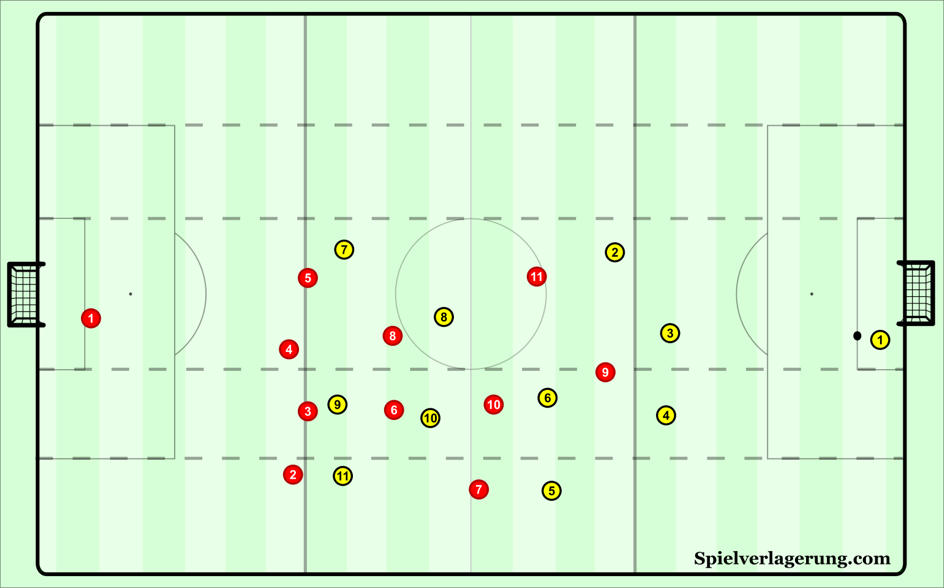

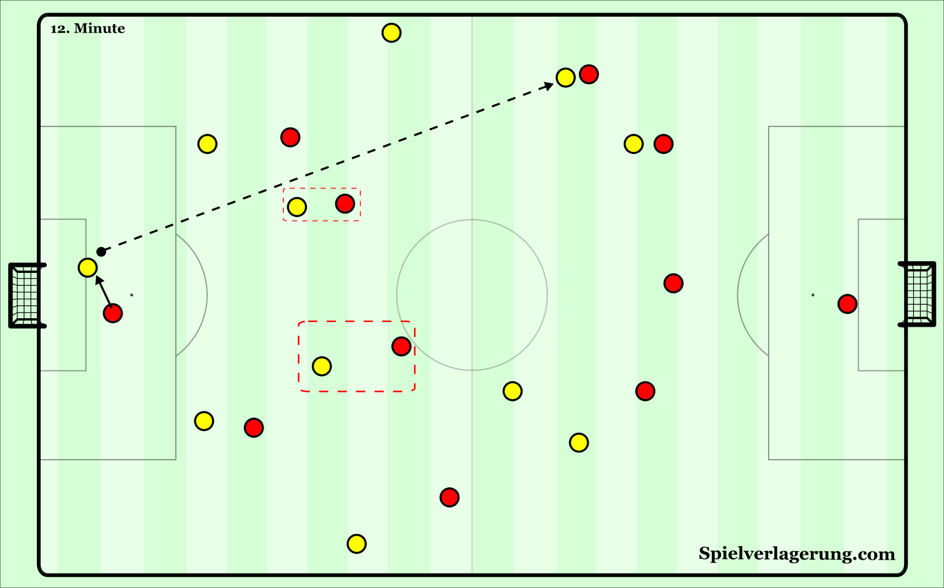

Most teams will look to get quite compact around the player at which the ball will be aimed. The width of most teams is about three vertical corridors, with the team occupying both corridors next to the player at whom the initial ball is aimed.

To give a practical example, when the goalkeeper aims to play the ball to the striker who is positioned in the left half space, the team will look to have a width from the outer left wing to the centre.

The only exception to this is when the ball is played to someone in one of the outer corridors. In these instances, teams will look to occupy the wing, the near-half space and the centre.

Most teams will look to play the ball to the striker in either the centre or one of the half spaces. As this allows for a multitude of lay-off options and gives you a bigger chance of counterpressing.

Another option is to aim the goal-kick at a wide-midfielder or fullback. As the receiving player is now positioned on the side, they usually have a more open body-position which gives them easier access to get a clean header on the ball. In addition, when the ball is lost it can be easily counterpressed as the space for the opponent’s is limited by the sideline. A principle Jorge Sampaoli amongst others have used in the past when regarding possession.

Finally, by playing the ball to the side, you also increase the chances of the opponent heading the ball over the sideline, allowing you to restart play in their half.

Most teams will use a 2-3 or a 3-2 rest-defence structure in case the ball is played beyond the first second-ball line. While also 2-4 structures aren’t uncommon, especially at teams that stay wider than 3 corridors when the ball is played. In addition, one player is usually a little more advanced than the player heading the ball, with one player just in front of the header in case he’s able to play it back. Most teams will than have 1 player just to the side of the player heading the ball, and one player staying wider on the opposite side of the field. Probably to ensure options to progress the attack in case they win a clean second ball.

In addition, the midfielders are almost always staggered and never in the same horizontal line to ensure a bigger reach to win the second ball.

Another option is to draw in the other team by also keeping a short build-up as a valid option. This works especially well if the opposition tries to press high up the pitch and needs to commit a lot of players in order to stop you from playing out underneath that press. By drawing them in towards your own goal, they have to open-up spaces further up the pitch, which you can exploit with a long ball. Also exploiting the fact that you can’t be offside on goal-kicks.

Defending dead balls

In order to defend long balls, in which you’re able to win the ball in a controlled way, it’s essential that you win the second ball and that the second balls ends up at a ‘free player’. This is a player who has time and space to receive the ball, without being pressed within the first couple of seconds. Especially on long ball situations this free player is quite essential to continue the play in a controlled manner because of the chaotic and random nature of the situation. It is also the situations in which this free player can’t be found by the defensive team that are highly susceptible to counterpressing. How the free players is found differs slightly over the three categories, but the necessity of this player is present in each of the situations.

For dead balls in particular the defending team gets into a compact shape around the area in which the initial long ball is going to land. One player will challenge the attacker to win the initial header, while there will be players positioned behind him to provide cover. What’s particular about the dead ball situation is the positioning of the player who challenges the attacker to win the initial long ball. Whereas this is usually a player positioned in the last line in the other two categories, it’s usually a defensive midfielder in the dead ball category. To give a practical example, when a team defends the long ball in a 4-2-3-1 formation, it’s usually one of the two defensive midfielder who goes to challenge the initial long ball while the four defenders take up covering positions behind him.

The fact that it’s more frequent in this category for a midfielder to challenge the initial ball probably has to do with the fact that this category is much more controlled than the other two categories. As mentioned, with dead balls, teams are able to completely control their structure and have time to position everyone into planned structures. By having a player in the middle of your structure head the initial ball, you have a more controlled structure to win the second ball. With players both in front and behind the ball able to press opponent’s in case they win the second ball. In addition, by positioning the defenders behind the initial header you prevent the opponent from playing balls (or second balls) directly into the space behind your defense which could lead to immediate goalscoring opportunities.

The free player to win the second ball in a controlled way can be created in numerous ways. First of all, the free player can be created by the two structures used by both teams. For example, if the defending team is using a 4-2-3-1 to defend the long ball and the attacking team uses a 4-4-2/4-4-1-1, you’ll often see that one of the two defensive midfielders of the defending team have time and space as there is no ‘natural’ opponent in their zone. When these players are able to pick-up the second ball they’re usually able to control it.

The second way this free player is often created is by pure randomness of the situation. As remarked before, in long ball situations (as with actually the whole game of football in general) a lot of what’s happening is random. A player can head the ball into the wrong direction or doesn’t get a clean contact, a player tries to press the initial header but he’s just too late. All of this can cause the ball to end-up at a free player between the lines who’s able to control the ball.

The third way has to do with the opponent having to stay in a covering position and therefore not being able to challenge the ‘free player’ immediately. I talk about this in more detail later in the ‘positional superiority’ section.

Another way to defend long balls is also to ensure the opponent isn’t able to create a controlled situation. This is mainly done by pressing the player with the ball before he’s able to control it. Which causes a lot of random and chaotic situations the opponents usually can’t exploit.

Chosen ball

The second long ball situation is a chosen ball. With a chosen ball I’m referring to situations in which a player has time and space on the ball and consciously chooses to play the ball long, hence chosen ball (and to think that my 6th grade teacher told me I wasn’t creative). The main aim of this type of long ball is to win the second ball in a controlled way and continue the attack.

The advantage of this type of situation is that there is little to no pressure on the player passing the ball, which increases the chances of the pass being on-point. In addition, as the player on the ball makes the conscious decision to play a long ball even though other options are present, this entails that it is usually a favorable situation to do so.

The downside of this situation is that it can be difficult to get into a fully organized structure. Usually at least one player will be in place to win the second ball, however in case that player doesn’t win the ball, there’s usually space for the opponents to gain.

In the chosen ball situation, the pass is usually made by a central defender, while this can also be a goalkeeper, a fullback, or a midfielder who’s fallen back. In successful situations (in which the second ball was won), the pass is usually played from the centre or one of the half spaces. It appears that the further the passer is positioned to the sides, the lesser the chances of the team being able to progress the play are. This might have to do with the overall cohesion of the team being lower when the centre back is in the outside lane. Or it might be caused be the more limited options on the ball a player has in the outside corridors.

Probably the most successful way to progress the play from this kind of situation is to play a direct ball to someone in either the centre or half space, usually the striker. Another player, (usually an attacking midfielder or a winger) is positioned in the same corridor just behind the player receiving the long ball, in order to receive a lay-off and continue the play.

This works best when the initial long ball is a direct ball that doesn’t have too much height, aimed at either the chest or head of the central player.

Another option can be to have the players who are positioned to win the second ball diagonally from the player receiving the long ball. When this is successful it provides more difficulty for the defenders to stop the attack as the defender who just moved out to contest the header can’t move up to contest the player receiving. Similar as to a striker having diagonal lay-off options when he receives a ball to feet.

However, in the case of a long ball it does ask of more control of the initial header of the ball. As the long ball has to be converted into a deliberate pass.

The third pattern I want to discuss in the chosen ball section, is a ball in behind the opposition’s defense onto a winger moving inside. As the run of the winger will usually cover quite a distance, it can be difficult for the fullback to follow him tightly. In addition, the fullback might try to play him offside, or to pass him over to another defender, which can cause communication errors.

In cases in which the winger is able to get some space and the pass is accurate, the winger can act as the receiving player, with the opposite winger and striker making runs to receive a lay-off from him.

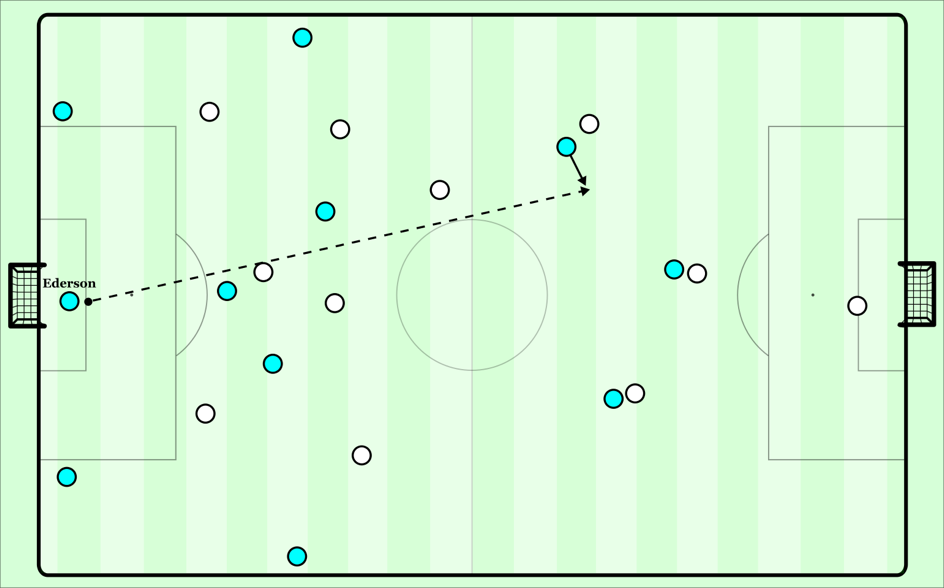

The last pattern in this category are balls played over the top for runners to receive in behind. The big advantage about this kind of passes is the fact that when the pass is accurate you’re immediately able to create goalscoring opportunities. When the pass is inaccurate and is intercepted by the defending team, you still have 7-8 players behind the ball who can take up defending positions.

The best moment to start the run, is when your teammate on the ball has space and time to give the pass. Ideally, the player making the run has a run-up before he crosses the offside line. This gives the player playing the pass the chance to spot the run and play the ball before his teammate has moved into an offside position. It also allows the runner to get up to speed, which creates a dynamic advantage against the defender.

In addition, it’s best when the receiving player makes the run on the blindside of the opponent. This increases his dynamic advantage, as the defender is not able to see the run which gives the attacker the chance to get up to speed before the defender has time to adjust. You’ll often see teams who have a player on the left make a run in behind when the ball is on the right and vice versa. The player passing the ball will usually be positioned in one of the half spaces. Passing the ball from the outer corridor usually makes the distance between the passer and the runner too big, while passes from the centre are usually too vertical and therefore have a bigger chance of being intercepted by the keeper.

There are certain pros and cons to the specific way the pass is played. When a left-footed player cuts inside from the right to play the ball in behind the defense to someone on the left, the advantage is angle of the pass as it curls towards the goal therefore increasing the chances of creating a direct scoring opportunity. However, the downside to this particular pass is that when the ball is overhit it can easily be intercepted by an attentive goalkeeper, after all the ball curls into his direction.

For a right-footed player playing the same pass from the right the opposite goes. The advantage is that the ball will bend away from the goalkeeper, therefore diminishing his chances of intercepting. However, the pass also has a smaller chance to become a direct scoring opportunity as the ball curves away from the goal.

This is of course also influenced by the characteristics of the goalkeeper. Some goalkeepers are very comfortable with coming off their line and protecting the whole penalty box, while other keepers are much more comfortable staying on their line and won’t intercept the pass as quickly. With the former the focus has to be more on balls that curve away from the goalkeeper in order to ensure that the goalkeeper isn’t able to intercept all the passes, while with the latter more risks can be taken in terms of the angle of the pass.

Especially against man-marking schemes this type of pass is often preceded by opposite movements. One player will move towards the ball and pull a defender with him which than creates space for another player to make the run. Some examples that I personally often see in the Dutch youth competitions (in which there is a heavy emphasis on man-marking)

are the striker dropping to receive and pulling a defender with him, which creates space for the attacking midfielder to make a run in behind. Or a common pattern on the wing involves the winger dropping into the half space, forcing the opposition’s fullback to make a decision. When the opposition’s fullback follows the winger, it creates space for the attacking team’s fullback to make a run in behind.

Defending Chosen Balls

The biggest differences between defending long balls in the chosen ball category compared to the dead ball category is the compactness of the team. In the chosen ball situation the team isn’t able to get into a pre-defined structure and therefore the initial header is often made by a player in the last line, instead of a midfielder as with the dead ball category. In addition this also places a larger emphasis on winning the initial header, as there’s now more space behind the defence and less players who can immediately press an opponent when they win the second ball. Just as with the dead ball situation it’s important for the defensive team to reach a free player in order to get into a controlled state again. A way to accomplish this that’s much more frequent in this situation compared to the dead ball situation is the winning of individual duels on both first and second balls. Whereas with the dead ball situation the spaces are much smaller and therefore there aren’t many one-against-one duels occurring, these duels do occur in this category. By winning the duel the defending team can be able to create the free player with either the player winning the duel immediately becoming the free player, or the player winning the duel being able to pass to the free player.

Forced Ball

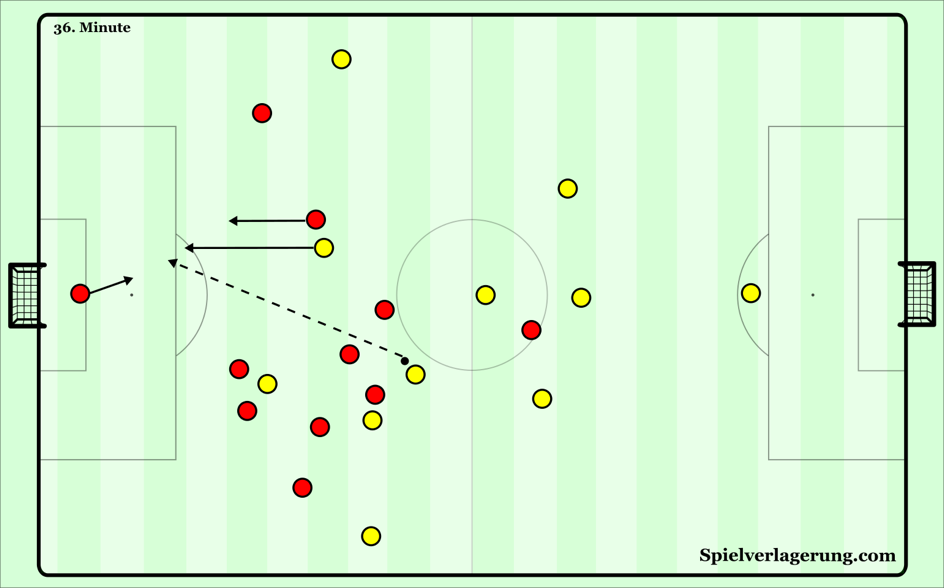

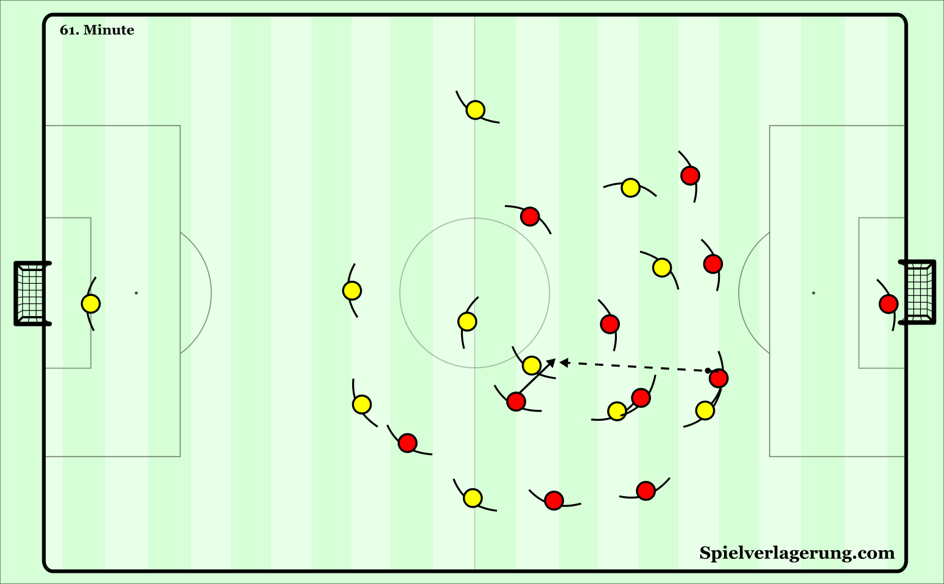

The last category of long balls are the forced situations. In this situation a player is being pressed and doesn’t have the time and space to find another solution and therefore decides to play long. Usually this is either (but not limited to) a ball played back to the goalkeeper after which a striker runs out to press the goalkeeper. Or a central defender near the side of the field who’s being pressed. The main aim of this type of pass is to gain space and move the pressure zone to the opponent’s half.

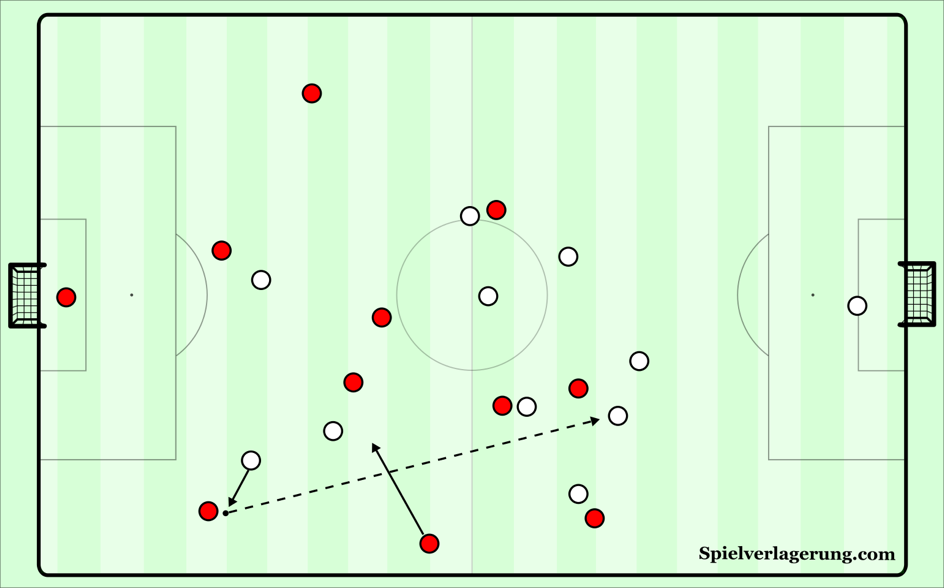

Usually in this type of situation the pass is aimed at the striker, who’s positioned in either the centre or one of the half spaces. In order to win the second ball, a player is usually positioned near the striker.

However, as these are quite uncontrolled situations (the attacking team isn’t able to define the structure before the ball is played) it’s not uncommon for the defender to win the header in this type of situations. Therefore, it’s important to have quite a layered second-ball structure.

When the defender wins the ball, he will usually head it forward with quite some speed. In the situations this happens, the ball usually goes over the players in the first line of the second ball structure. By keeping a layered positioning, you increase the chances of winning the second ball.

From all three types, the forced ball situation is usually the one which is the least ideal in terms of winning the second ball. The player playing the long ball is under pressure, so isn’t able to play an accurate pass. Your team usually isn’t compact. And as this type of situation is usually preceded by a situation in which you tried to build-out with short passes, your midfielders are positioned lower than the opponent’s midfielders. Increasing their chances of winning the second ball.

Yet, there are situations in which this positioning is actually a downside for the midfielders of the defending team. When they are just moving up to press the central midfielder of the opposition, to prevent a short pass into them, the ball can be played long. This would leave them in a dynamic disadvantage, as they were just moving into the other direction they will need more time to adjust, allowing the midfielders from the attacking team to get in front of them and win the second ball.

Defending forced balls

Defending forced balls is quite similar to defending chosen balls. The initial header is usually executed by a player in the last line and it’s important to win the duel (or at least not lose it). Because the passing by the attacking team is less secure it seems that it’s easier for the defending team to win the header, however I don’t have the exact data on that.

Because the attacking team usually isn’t in a compact shape, the player winning the second ball is quite often also the free player or able to reach the free player. While situations also occur in which the pass is off, resulting in an unpressed defender picking up the ball which immediately makes him the free player. In this situation it also seems that the attacking team makes a lot more mistakes with balls that are headed towards teammates that are overhit, misdirected or there is miscommunication between the two players. Which seems to show that in this situation it can be the case that enough pressure on the initial header and enough players back in covering positions can be enough to force the attackers to make mistakes.

Counterpressing on Second Balls

Long balls can be excellent situations to apply counterpressing, especially the dead ball and chosen ball situation, as you have control over the structure of your team. In addition, as the ball is difficult to control it’s hard for the opposition to play out underneath the press within the first couple of passes. Especially as they usually lack width themselves as they just moved into a compact shape to defend the long ball.

Ideal balls to counterpress are balls that neither team is able to get a clean header on. For example it happens quite often that both the attacker and defender jump for the ball, which results in the defender heading the ball against the back of the attacker, causing the ball to drop a few meters away.

Counterpressing on second balls is usually either space- or man-orientated, or a mixture of the two. Man-orientated counterpressing will often be seen in situation in which the opponent’s win the initial header and have players positioned to receive a second ball without pressure. By applying man-orientated counterpressing the team ensures that all players are pressed by a direct opponent and aren’t able to play controlled passes to get away from the situation (and get to the open space on the far-side).

Space-orientated counterpressing is often seen in situations in which the second ball falls between multiple defensive lines. Causing the back line to press forwards, and the higher line to press in the opposite direction, which condenses the space between the lines.

Passing-lane orientated counterpressing is very unlikely to be seen at second balls, as it is an uncontrolled situation and the ball is usually still in the air, or at least bouncing. If you were to apply passing-lane orientated counterpressing you would run into the difficulty of orientation on the passing lanes. The players are focused on the ball and it’s (nearly) impossible to keep focusing on a long ball while also checking your shoulder to ensure you’re still taking out the passing lane. A second problem would be that as the ball is in the air, it’s not unthinkable that the ball is headed over (or bounces over) your players who try to apply counterpressing. Which could result in the ball ending up by the player that was previously in your players covershadow, who’s now free to receive.

Transitioning into a press

Another category of counterpressing on second balls is the immediate transition into pressing after the second ball is lost. In order to understand this it’s important to understand the concept of a pressing trigger. A pressing trigger is a pre-determined moment in which it is favorable to press, therefore when one of these ‘triggers’ occurs in a game it is the signal for the entire team to start pressing. Examples of this are players receiving with their back to play, players receiving inaccurate balls (balls that are bouncing), or a fullback receiving.

The same triggers apply in long ball situations, however on second ball situations these triggers are much more common to occur. This actually makes quite some sense when we consider that a bouncing ball/ a high ball are considered pressing triggers. When the ball is played long, the ball is always going to be high, and the second ball will in numerous occasions be a bouncing ball. Therefore, a lot of teams that lose the second ball will continue by immediately going into a high press to win the ball back or force the opposition into making mistakes.

Some examples of common pressing triggers on long balls are:

- A player with his back to goal. On occasions in which the ball is extended by the attacker towards the opposition’s goal, or the defender heads it towards his own goal, the following scenario is usually the defender running back towards his own goal to win the loose ball. This provides an excellent opportunity to press him, as his field of vision is limited due to his body position. This type of pressing becomes even more effective when one player (usually from the far-side) immediately makes the run towards the goalkeeper, to take him out as a potential passing option. As he is usually the only option the defender running back towards his own goal has upon winning the ball.

- A player receiving on the side. In open play a very common pressing trigger is to press the fullback upon receiving. The fullback is usually positioned in the outer corridor, therefore his range is limited by the sideline on one side. In addition, it’s very hard (even for professional players) to play a ball from one side of the pitch, directly to the other side, so the fullback’s range on the other side consists of the near-half space and centre usually. This lack of options explains why a lot of teams exploit this by using it as a pressing trigger. The same thing goes for long balls, when the second ball is won at the side it’s very difficult to get out from the pressure zone and switch play to the far-side. Especially in the dead ball situation, the team playing the ball to the wing will also have their rest-defence organized in a way that ensures they’re able to press the second ball, making it even more difficult to get away from the pressure. This might also explain why certain managers choose to aim their long balls to either the fullbacks or wingers, who are positioned on the sides. It diminishes their own chances of creating a scorings chance from the long ball, but it ensures they’re immediately able to trap the opposition in the side in case they’re able to win the second ball.

Backwards (counter) pressing on Second balls

A form of (counter)pressing second balls that’s especially effective is backwards pressing from the blindside of the opponents.

If I were to throw a ball and ask you to calculate exactly where that ball is going to land, taking into account the angle the ball is thrown in and the speed the ball is thrown with, you will probably have a hard time to figure it out. Let alone if you have to make the calculation in the couple of seconds before the ball has reached the ground.

Luckily for us, our magnificent brains are able to make this kind of calculations within seconds. There is only one pre-condition to making such calculations: you have to keep your eyes on the ball.

If I were to throw you a ball, and just after it is released from my hand you have to look around and still catch the ball this will prove to be quite hard for you. The same goes for heading a cross: you have to keep your eyes on the ball if you want to make a clean contact with it. Were you to look around just after the cross is played, you lose eye-contact with the ball and your timing will usually be off.

To put it shortly, scanning in a long ball situation is practically unlikely and is probably even counter-productive. Just as it would mean in open-play, this entails that a players field of vision is fairly limited. He’s only able to see the angle he’s directly looking at, which increases the angle of space he isn’t looking at (his blindside). In open play there’s a big emphasis on learning players to be constantly scanning in order to reduce this blindside, however as mentioned this is impossible to do in high ball situations. Therefore, the possibilities to exploit other player’s blindsides increases massively.

Some examples:

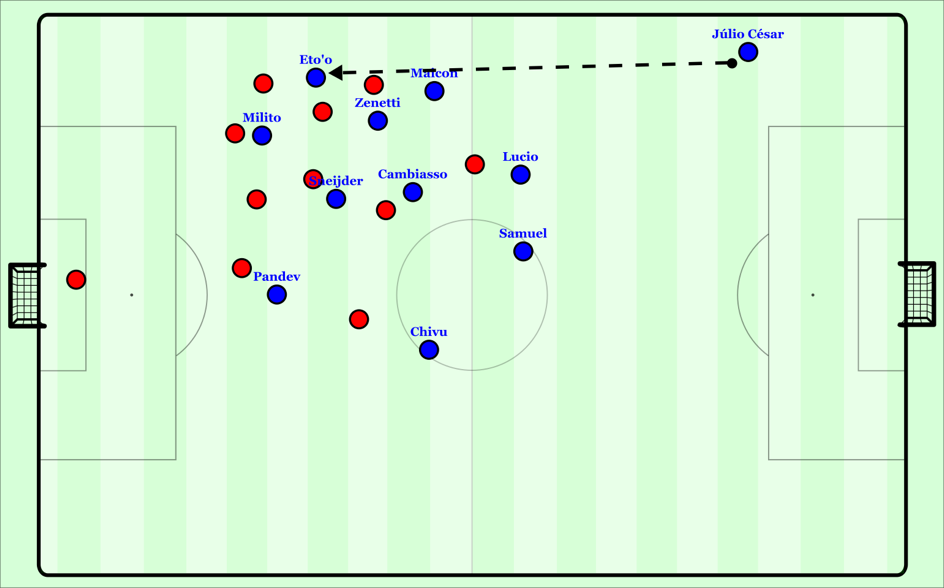

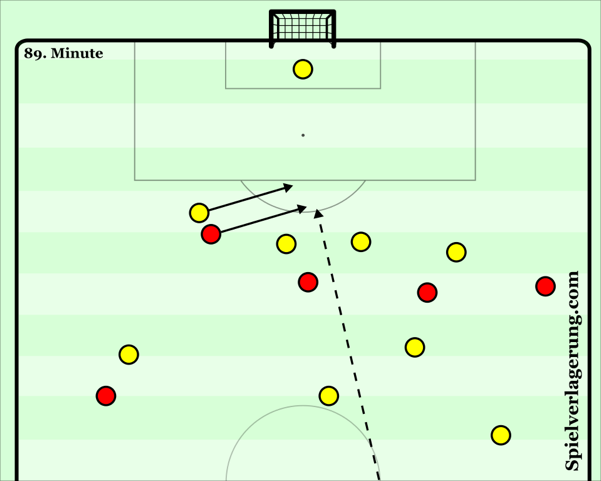

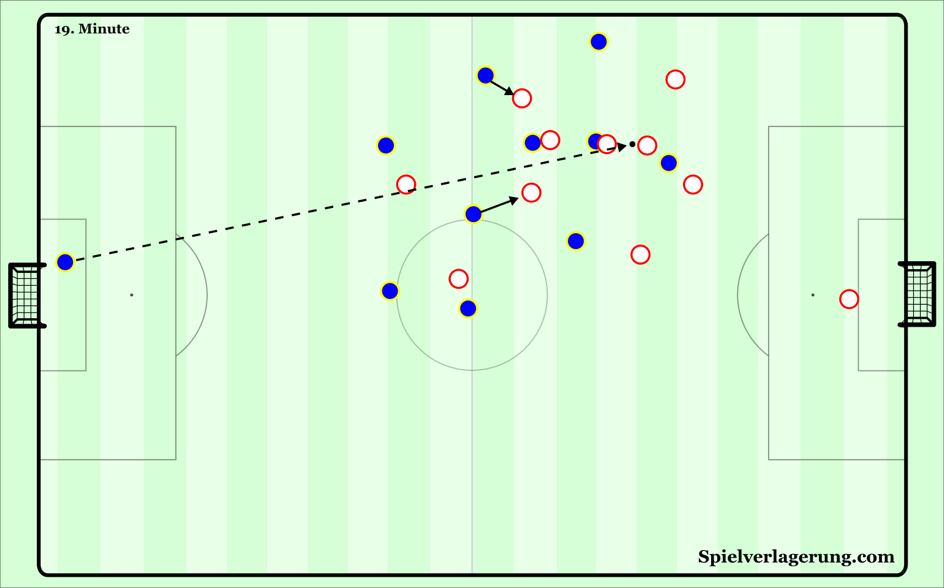

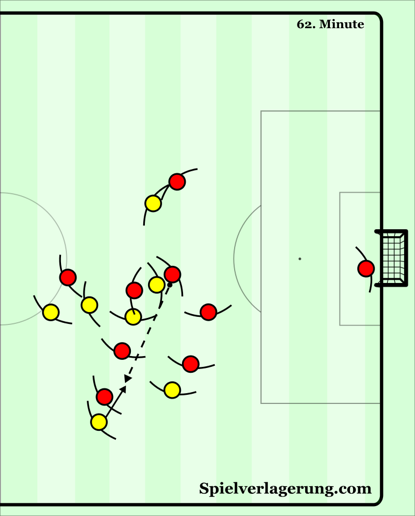

- The striker of the defending team uses backwards pressing in order to win the second ball:

This situation usually starts with a long ball from the back, after which the central defender of the defending team gets a clean header on the ball and heads the ball towards the opposition’s central midfielders who look to win the second ball. However as the ball is bouncing the central midfielders will usually only be looking at the ball, not aware of what the striker is doing behind them. This allows for the striker to apply backwards pressing and get out of the blindside of the central midfielder in front of them to win the second ball.

This is also a reason why it can be beneficial to play back to your goalkeeper and wait for the opposition’s striker to move out of the structure and press him, as this diminishes the chances of the striker to be able to win the second ball by pressing backwards as the distance becomes too big.

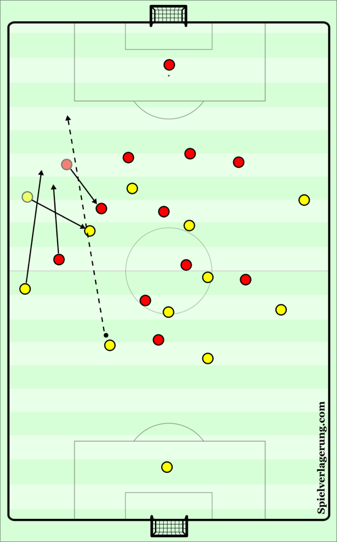

- The fullback and winger getting in front of each other

As the ball is aimed at a player in the half space the winger and opposing fullback will be looking at the situation from a diagonal angle directly at the ball. As they are on the sides of the field this allows them to have quite a wide field of vision, however they are usually in each other’s blindsides. The fullback being in the blindside of the winger appears to be more common, however it also happens the other way around with the winger stealing the ball away from the full-back.

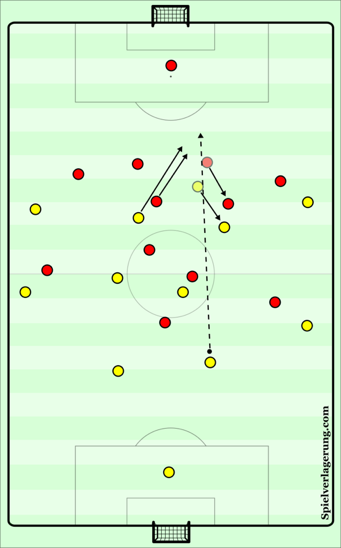

- Central midfielders moving in front of each other:

This one is similar to the backwards pressing movement of the striker. As the opposition’s central midfielders are looking to win the second ball they are focused on the ball and are therefore not able to see what’s happening behind them. This allows the opposition’s midfielder to use backwards pressing out of their blindside to win the second ball.

Positional Superiority on Long Balls

Within the philosophy of positional play, there is often a large focus on the ‘creation of superiorities’ in order to progress the ball up the field. Similar concepts can be used here in order to progress the play from a long ball. Especially the concept of ‘positional superiority’ can be utilized in long ball situations, even though the nature of the attack is quite different.

In his article on Juego de Posición, Adin Osmanbasic wrote: This is a superiority of space or positional superiority. In this form of play the players are arranged at various heights and depths. This staggering creates interior spaces and passing lanes within the opposition’s formation. There is a large focus on the spaces “in between the lines.” Players look to position themselves in areas between the opponent’s horizontal and vertical lines of defense.

A good example of positional superiority within the philosophy of positional play is the positioning of players within ‘the boxes’ of the oppositions lines. The big advantage in doing so is that no matter which opponent decides to move out and press the player between the lines, it always opens up certain spaces that other players could potentially exploit.

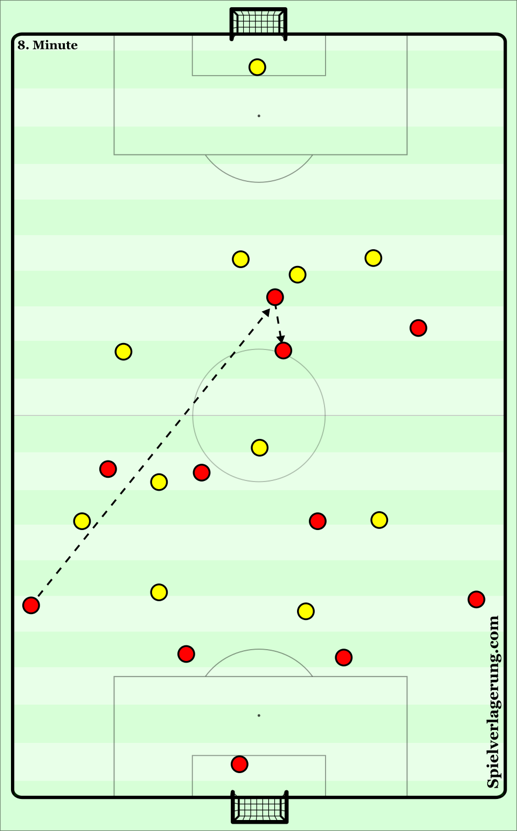

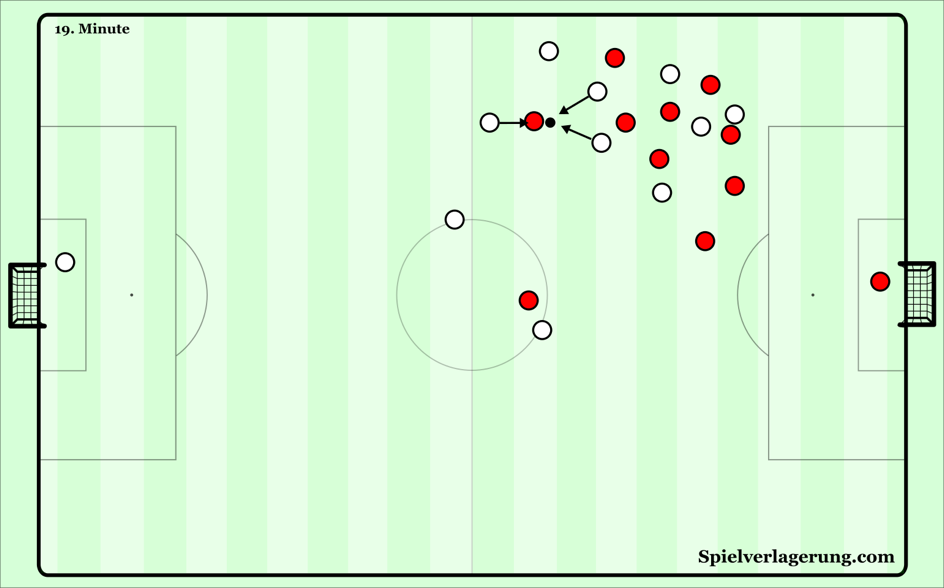

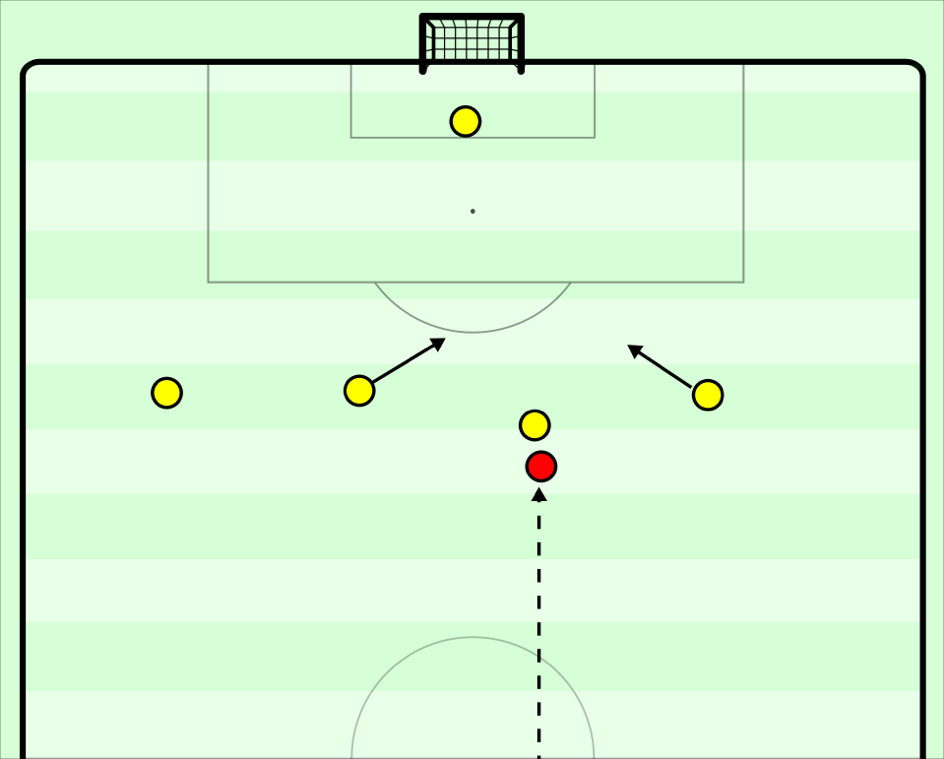

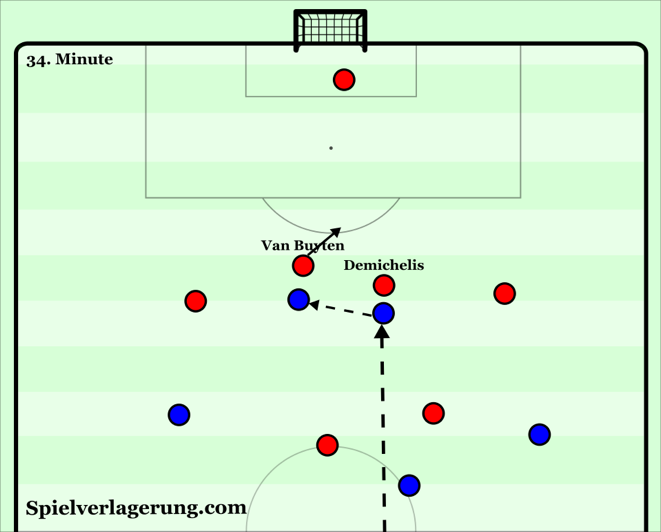

This concept can also be used in long ball situations. When the ball is played long to the striker, and the left centre back decides to move out and contest with the striker to win the initial header, the right centre back and left fullback have to tuck inside in order to get into a covering position. If they decide to not get into this covering position, they leave space in behind them open, which could potentially be exploited if the ball is headed into that space.

As the right centre back and the full-back have to get into a covering position, it can be usefull to position a player in front of them, as this forces the defender to make a decision. Just as with the idea of a positional superiority, this creates a situation in which no matter what the defender decides to do, space always opens up on either side of him.

If the defender decides to get tight on the player positioned in front of him, than he leaves space open behind him. Which can be exploited when the striker heads the ball into that space and other players make runs to win the second ball. If the defender decides to get into the covering position and take away the space behind him (which is the most logical thing to do considering the risk-reward outcomes of the choice, and therefore what happens usually in these type of situations) the player positioned in front of him is able to get free and receive a second ball.

Another concept that can be translated from Positional Play to long ball situations is the concept of ‘qualitative superiority’. As Paco Seirul-Lo phrased it: “There’s numerical, positional and qualitative superiority. Not all 1 vs. 1’s are a situation of equality.”

Within the context of Positional Play this concept can for example be utilized with an ‘overload to isolate’. The idea is to build-up over one side of the pitch in order to attract the defenders to that area. Once the defenders have shifted over to the side of the ball, you quickly switch to the far-side of the field where you’re able to create a temporary 1 v 1 situation. When the player you get on the ball in that 1 v 1 situation is a player with more qualities in a 1 v 1 than the defender he’s up against, we speak of a qualitative superiority.

Within the context of long ball, 1 v 1 situations are also created, usually the initial header consists of one player from either team jumping and trying to win the header for their team. In this situation a so-called ‘qualitative superiority’can also be created when one of the players has more skills to win the header than the opponent has. Either one of the players might be taller, stronger, jump higher or has better heading skills than the opponent. Increasing his chances of winning the duel.

An example of how this can be utilized in a match is the striker (to whom the long ball is aimed) positioning himself near the ‘weaker’ of the two central defenders. By positioning himself there, the striker increases his chances of winning the header as he has ‘better heading skills’ than the opponent he’s now up against.

Final note

In this article I have mainly focused on vertical long balls that are headed backwards and the possible situations that might arise in order to win the second ball. I again want to stress that there are situations in which the ball is headed forward, for teammates to run in behind. However at the highest level these type of passes are usually defended very well and therefore don’t arise as much as balls that are headed backwards in order to win the second ball. Nevertheless, balls that are headed forwards shouldn’t be neglected by coaches when thinking about possible strategies to utilize long balls with their own team.

Written by Evert van Zoelen

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Almaster August 23, 2020 um 12:27 pm

Great article! I would just add one aspect that I think is not explored in detail, especially in the chosen ball. Passing to the head of the striker/teammate or the chest or feet makes a huge difference in the lay-off he can take.

Also, especially in the chosen balls we can prepare our team to be disposed in a certain way that will open the spaces in front of the opponent’s defense, therefore increasing the chances of a lay-off and having the second ball controlled and facing the opponent’s goal.

Chris August 25, 2020 um 8:43 pm

It is interesting your point but you need to bear in mind that a long chosen ball in which in this article is talking about 50-70m distance, a ball controlled with the chest is as difficult as trying to controlling with the foot, still the probabilities of laying off the ball to a teammate is very complicated and is still a massive cue for a defender to snatch out the ball.