VfB Stuttgart under Pellegrino Matarazzo

VfB Stuttgart did it. One year after their promotion they made it back to the 1. Bundesliga. Having moved from Hoffenheim to VfB at the end of December 2019, head coach Pellegrino “Rino” Matarazzo, led the team to this success. What kind of football does the Italian-American focus on and what are the prospects for the upcoming challenge in the first division?

Background on the signing of Matarazzo

It was an exciting start for Pellegrino Matarazzo into the year 2020. Shortly before the turn of the year, he was named head coach of VfB Stuttgart, following on Tim Walter. The principal decision of those responsible for him root in his experience in developing players during his time at TSG Hoffenheim and 1. FC Nuremberg. Hence, he was brought to a position in which he had two principal tasks: First and foremost, Matarrazzo should bring the first team back in the first Bundesliga. Second, he should integrate several youth players in the first squad in the long term.

Before the season, the squad was clearly assembled to manage these both goals, promotion and player development. An average squad age of 24.3 years and 17 players of age 23 or younger, indicate the focus on player development. The squad is balanced with young talents such as Wamangituka aka Silas, Mangala, Gonzalés and Kobel, players in the middle of their careers such as Kempf, Endo and Klement and experienced players such as Badstuber, Castro, Didavi, Gómez and Al Ghaddiouni.

In the following this article will examine the performance of the VfB Stuttgart under Matarrazzo. Doing so, we will explore how Matarrazzo’s playing style works and how it has played out on the pitch in the Ruckrunde. By considering the major strengths and weaknesses, what is the potential for the future in the Bundesliga?

Matarrazzo favors dominant and proactive playing style

Matarrazo’s idea of football is centred around controlling the game in all of its phases. That does not necessarily mean, however, to possess the ball much more than the opponent, but to be able to determine the actions on the pitch even when the opponent has the ball. At this point it already becomes clear that counter-pressing and transitions are vital of the Matarrazzo football idea. He says: “Sure, most teams want to dominate and control the opponent’s actions. But the differences lay in the details.”

To explore these details, three aspects will be considered in how Matarrazzo’s VfB wants to dominate games. First, their build-up and structure favourable for counter-pressing opportunities. Second, how his team has dealt with the constant trade-off between risky, value-creating passes and dangerous ball-losses. Third, the role of the play against the ball – from a current standpoint but also a future outlook.

1) Build-up and play in ball-possession

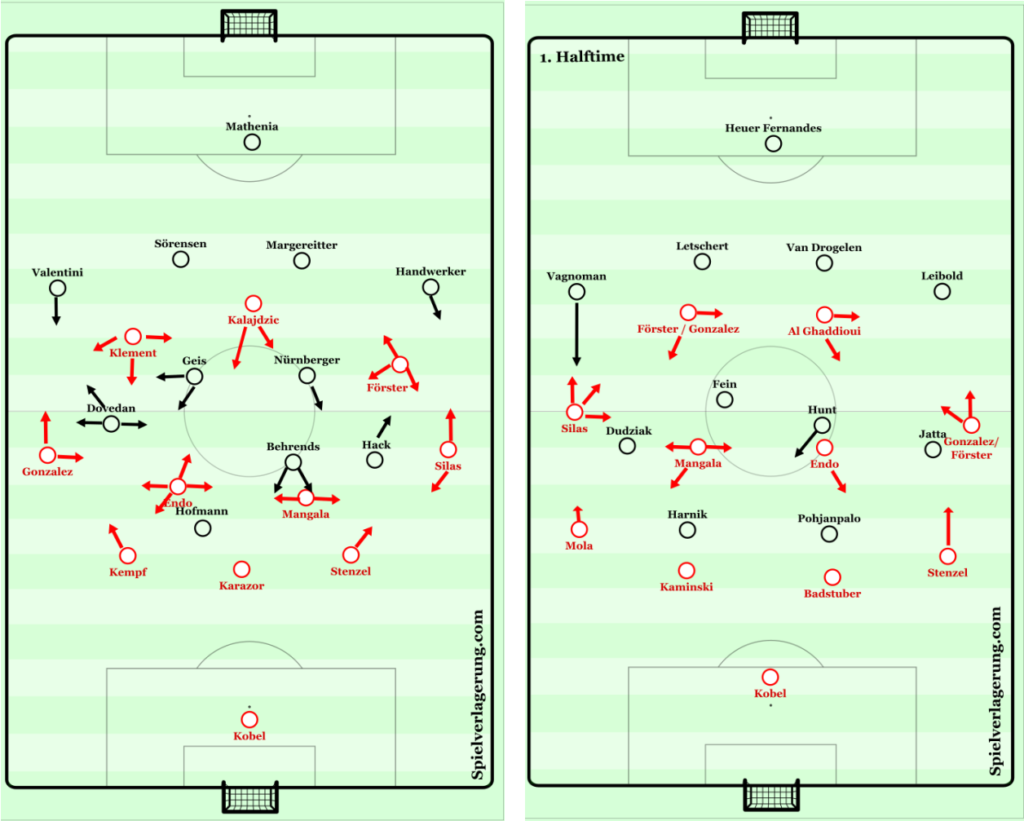

During the season, the basic system and structure of Matarazzo´s starting 11 differed. Early in the Ruckrunde, the VfB started many games with a back three varying between 3-4-2-1 and 3-3-2-1 with specific deviations in the respective phases of the game. Then, at another point, the VfB fans could observe formations with a back four (e.g. 4-1-4-1 and 4-3-3). Matarrazzo decided for this latter option especially against teams of greater quality such as Leverkusen in the DFB-Cup, Hamburg, Bielefeld and Heidenheim. At the times of the respective games, the coach arguably considered the own structural patterns in own ball positions as not established enough to cover own attacks against these opponents. The distance between players and timing for movements “were still under construction” in this part of the season to cover own attacks through appropriate structures for counter-pressing situations. Furthermore, the areas behind the wingbacks were potential areas of danger which presumably played a major role for the decisions for 4-4-2 – formations against such high-quality opponents.

Nonetheless, the final breakthrough happened with an evolution back to a 3-4-2-1 late in the season. This system laid the foundation for the clear victories against Sandhausen (5:0) and Nuremberg (6:0). This formation and its characteristics align with the Matarazzo’s idea of football to the greatest extent as we will see in the following. Hence, this formation will most likely be his system of choice for the future.

One of the focus areas of Matarazzo was the build-up phase with ball possession against a structured opponent. This role was both deliberately chosen and naturally given due to the role as favourite team of the VfB in most games. In the second Bundesliga the majority of teams focus on solid structures against the ball and transitions in the offensive for counter-attacks. Hence, the VfB needed solid mechanisms for the play with the ball from deeper zones. Three of such collective patterns could be observed regularly.

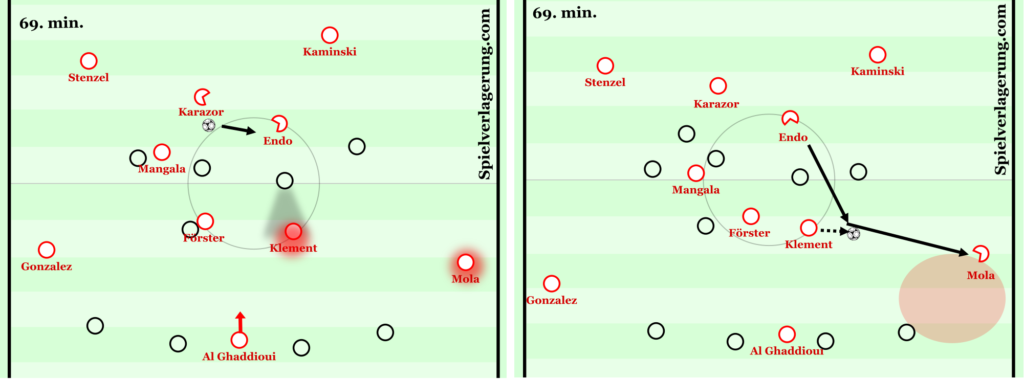

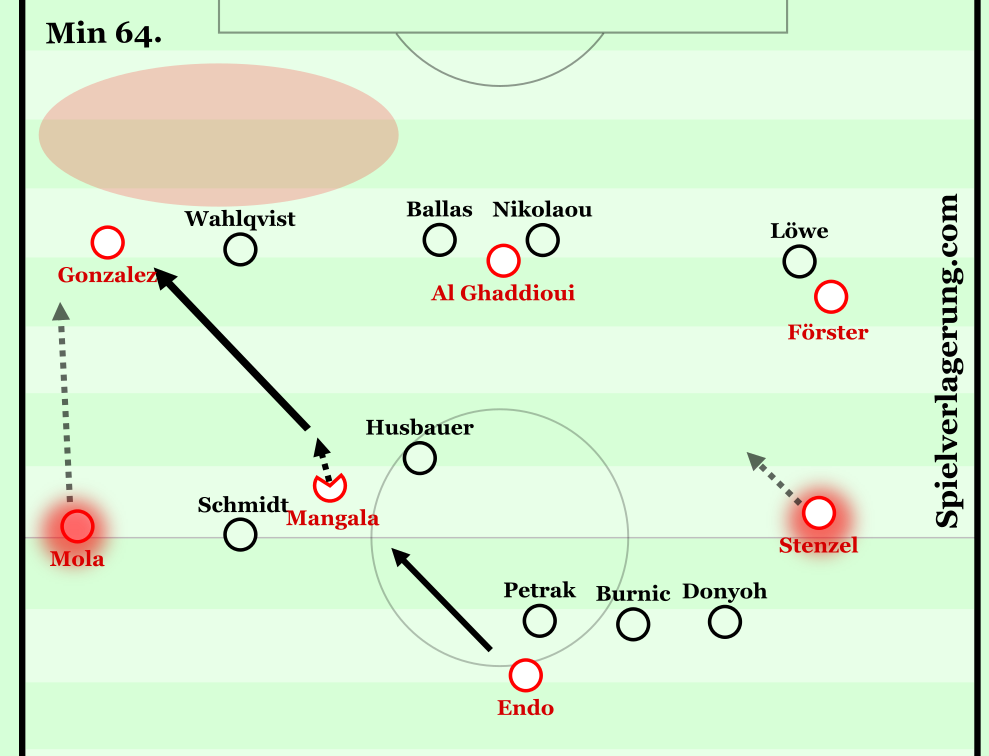

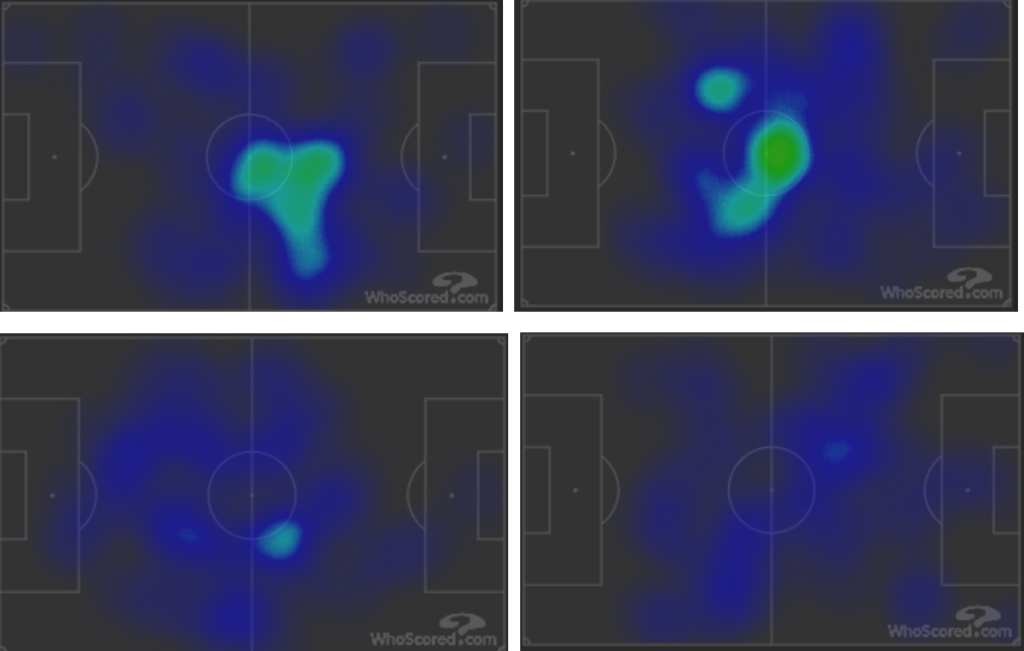

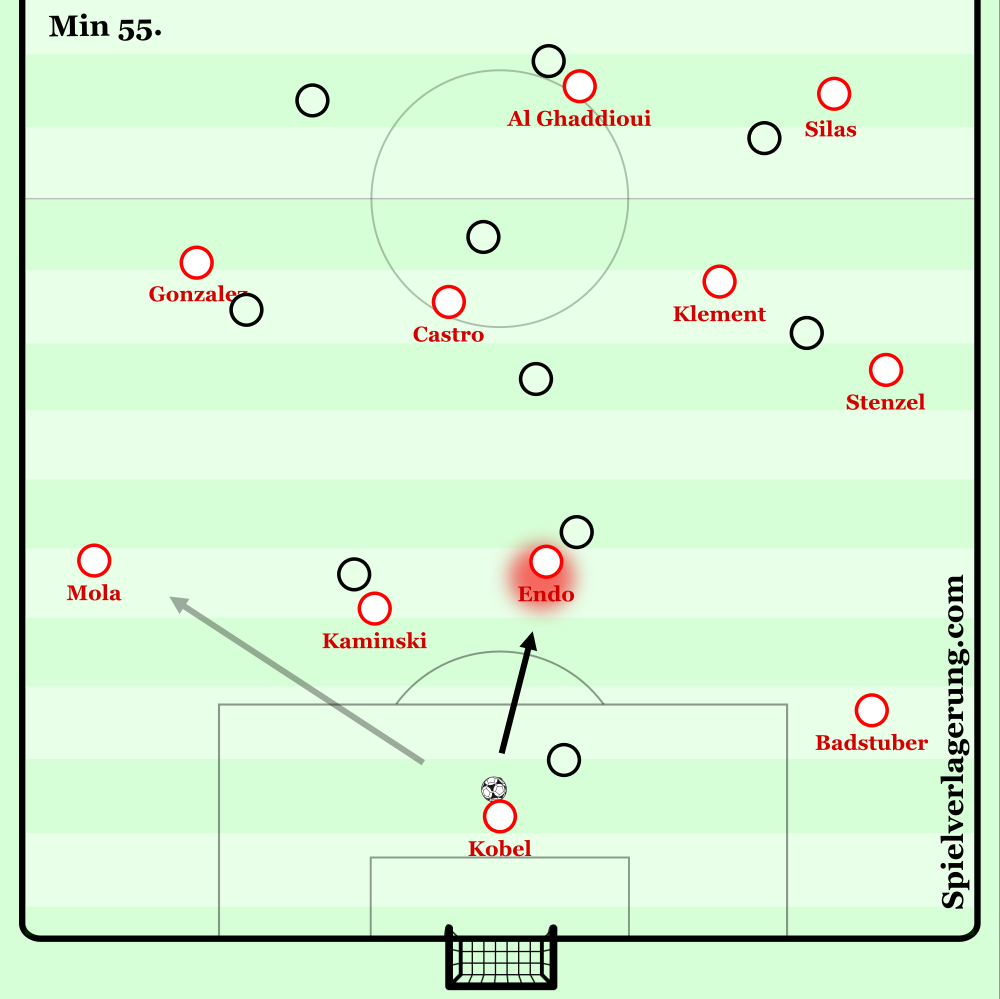

The first mechanisms in the build-up involves the pattern of a rather short diagonal or even horizontal pass followed by quick a turn of the receiver and a vertical pass into higher zones. While early in the year, such movements were done too schematic, improvements could be observed over time. Regularly, such simple ball movements in combination with appropriate timing in zone occupations helped to effectively bring the ball in higher zones. Especially Endo was a key player to act as player to constantly support the build-up and transition in higher zones in these ways. The heat maps of Endo in figure 4 show despite his focus on the central zone – especially in a 4-1-4-1 – is quite active and versatile with his movements during own ball-possession, but also against the ball by moving up aggressively with good timing. Also, Mangala or even occasionally Castro showed good moments and timing. The scenes depicted in Figure 2 and 3 illustrate such mechanisms in the games against Nuremberg and Dresden respectively.

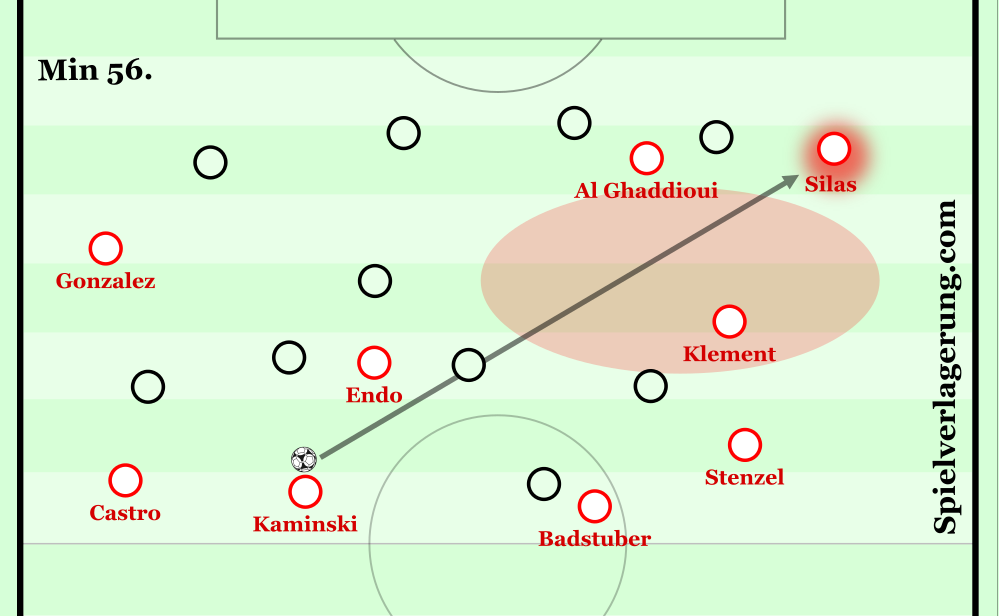

A second mechanism in the build-up relates to diagonal long balls for side shifts. To be able to play such passes, the collective position is crucial. The balance between the occupying wider zones and providing sufficient options for the ball carrier in the ball-near zone was a delicate challenge. Additionally, the balance between occupying wider zones and establishing favourable structure for counter-pressing movements appeared as a great challenge throughout the entire season. Here the VfB showed a positive development with great performances in the last games. We will look at this balancing act at greater depth below. For the moment, we can ascertain that the creation of structures for long diagonal passes was on Matarrazzo’s list. Figure 5 shows one example from gameday 33 against Nuremberg. Silas is positioned out wide on the right wing. Simultaneously, Al Ghaddioui binds not just one centre-back, back also the wing-back. This provides valuable space and seconds for Silas to receive the long ball. Noteworthy, such long passes were far more often played diagonally from the left to right. The reason for this is that the defenders Kaminski (plays the ball in this scene), Badstuber and Kempf are all left-footed. Moreover, in the scene below the right central defender, Badstuber, is left-footed. Hence, there were far less opportunities to play a similar ball from the right deep zone up the left wing in several games.

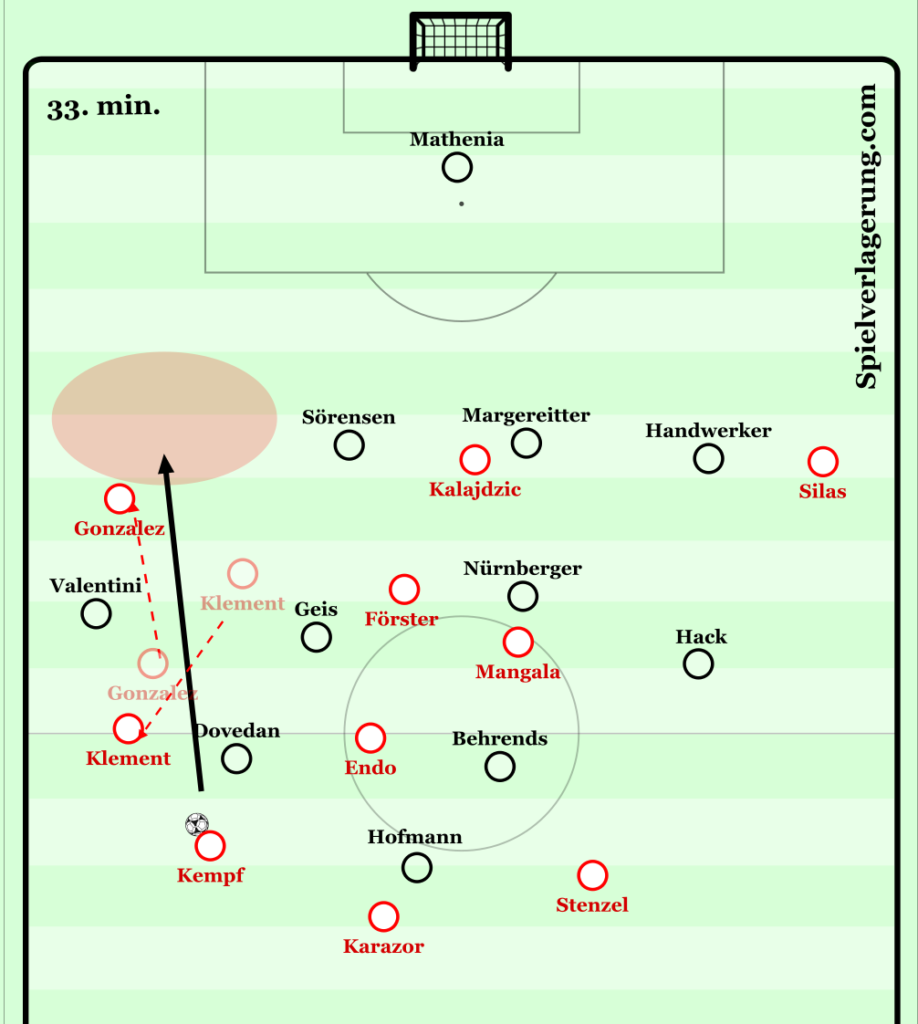

A third collective pattern used to create dynamic in the build-up include positional switches with reverse runs of two players. Most commonly, this mechanism was exerted between the player on the 8 and the wing-back. Figure 6 illustrates such a scene. Kempf has the ball and looks for options in higher zones. Klement drops deeper to circumvent the oppositional cover shadow. At the same time, he increases the empty space in the left half space and on the wing. Gonzalez can move up to receive the ball. The reverse runs confuse the Nuremberg players for a moment.

What’s missing – further room for improvement

Clearly, the next step when it comes to build-up is the patient and strategically preparation of attacks. As seen above the team already shows good approaches. Over the entire Ruckrunde, these mechanisms were applied too individually and too inconstantly though. Especially against well-structured and rather defence-oriented teams – teams that can be expected in the 1. Bundesliga more frequently – the collective mechanisms need to be played in a more coherent context. For instance, a more patient and foresighted movement of the ball in build-up would be a of great extension of the status quo. This would help to deliberately prepare the right moment to bring the ball in higher zones. Consequently, a combination of a better circulation of the ball together with established patterns can be the next step in the development.

For example, the players on the 8 or the wings-backs could be integrated in ball circulations and attracting the opponent in certain zones before quickly moving the ball for shifts or other vertical options. Of all teams, it is for example Matarrazzo’s former side TSG Hoffenheim, that has demonstrated a good build-up after the re-start. This is not to say that other teams are necessarily weaker here, but possibly just lay a different emphasis.

While the mechanisms shown above with mere passes in the half-rooms were well played, there will be less teams that offer that much space and time for turns in the 1. Bundesliga. Therefore, the current mechanisms could be extended through further collective patterns. One example could be to integrate lay-offs. Simply put: After a vertical pass from e.g. Endo (or Mangala) to central forward Kalajdzic, the Japanese could move up to receive the it and bring up dynamic in the higher zone. Such lay-off-combinations could also work together with players on the 8 in the half spaces. Additionally, a third player could be involved. Receivers could then be a player on the 6 (e.g. Endo, Mangala) or the wings (e.g. Silas, Gonzalez). Essential for such mechanisms to work is not the pass itself, but rather the positional structure, and identifying the right moment to apply it.

A second example relates to long balls from the half-defenders after patiently building up and pulling the opponent slowly out of positions – similar to the scene in figure 5, but more focused on passes behind the opposition’s last line. After attracting the opponent in zones higher that he actually planne on, horizontal shifts to the other side could be made. Then, direct passes between the lines in the half-spaces or even deep behind the last line for the starting wingbacks could be promising. Definitely, Gonzalez and Silas are players that could leverage their dynamic, athleticism and strength in such scenes. A situation in which this was really well played was the scene when Hoffenheim scored 1:0 against Koln with link central defender Hubner’s long ball to Larsen (gameday 28).

In fact, the VfB already demonstrates patterns in which they move the ball within a small area with rather close positions between the defender and midfielders to attract the opponent in this very area. However, so far the VfB has not used such scenes deliberately to their advantage to prepare shifts to the other side. Positioned in short distance to the ball-carrier and under opponent’s pressure, central midfielders (e.g. Endo), did not help to develop the build-up-situation favourably. For example, in situations when the half-defenders possess the ball, their colleagues in midfield sometimes requested the ball early in the build-up too ambitiously. In other scenes Endo was given the ball either to early or late, or he just held on to the ball too long. In such ways, the VfB covered own vertical passing options for the ball carrier, limiting the further development of the play. Other disadvantages included the unnecessary increase of pressure for either the ball-carrier or the receiver. In such situations the team needed more foresight and collective sense for the opponent’s movements. Figure 7 gives one example for an inappropriate decision for a short pass to solve a situation. Here the goaly Kobel is involved. In most other situations the disadvantageous pattern happens when moving the ball from a central defender to the midfield in relatively narrow space with no clear idea to leverage pull-outs. Patterns with ball circulations in rather small spaces could be used to pull out opponents before shifting to the other side or in higher zones when pass channels open up. Overall, such movements are currently not always used to the own advantage and provide greater potential for the future play.

Nonetheless, in the upcoming season in the Bundesliga the opponents will be of higher quality and hence the strategic focus might concentrate on something of great importance for this idea of football: transitions in the offensive after losing the ball.

2) Risk in build-up: A constant trade-off between value-creating passes and dangerous ball-losses

One of the central topics of Matarrazzo’s team was the creation of chances through favourable risk-taking in ball-possession while balancing the risk of ball-losses. While Stuttgart dominated the happening in several games, they depended too much on individual moments instead of a solid team performance, or more specifically team- and group-based patterns. One of the best examples encompass transitions into the defence after ball losses. Over a longer period, they were vulnerable to opponent’s counter attacks. The coach’s ideas for structures favourable for counter pressing movements was a constant point of attention. On the one side the VfB played too careful, limiting the dynamic of situations or not playing the pass in dangerous zones. Thereby, winning time and space through actions such as passes and runs for following actions was not optimal. On the other side the team conceded goals after such passes through simple counter attacks. After conceding such simple counter-attacking goals despite dominating the game, the team seemed hindered to take up more risks when moving the ball in more offensive zones. Such setbacks initiated a somewhat vicious cycle as it inhibited risk-taking passes even more. For a while it seemed that this trade-off could hinder the team to bring about a decision in the promotion. With some adaptions, it was in the final period in the season that the VfB found this balance against Sandhausen (5:0) and Nuremberg (6:0). Structure was the key for improvement. Matarrazzo focused on encouraging risk-tasking behaviour in the offensive zones while limiting the potential danger. In this context the switch back to 3-4-2-1 – system played an essential role. Various factors within this new formation were important.

First, the VfB was better positioned in the build-up phase. As mentioned, against most teams they were strategically and mentally in the situation to open the game with ball possession in deep zones. With the Back three against Sandhausen and Nuremberg, the VfB better occupied different zones and lines – both vertically and horizontally – more constantly on a high level. Such better positioning provided qualitatively and quantitively more options when moving the ball (e.g. figure 2 and 5). Specifically, the already existing mechanism such as the short horizontal pass with a following vertical pass in the half spaces could be better utilized due to more space in the central zones. The wider positioning of the wing backs Silas and Gonzalez and their discipline in occupying and timing in occasional horizontal runs inside helped enormously. At the same time the half spaces were not occupied constantly and static, but rather more flexible with dynamic runs and by different players. All of this contributed to a greater variability and greater challenge for opponents to defend vertical passes. Before these delicate improvements, it was often sufficient for opponents to defend against Stuttgart’s build-up with simple shifting movements and man-oriented covering.

Second, the positioning of the deep zones was better. On the one side this helped to create more space between the opponent’s last line for drop-offs and taking up dynamic from rather stable situations. On the other side is allowed to attack the deeper zones through pulling out defenders through positional dropping and attacking the space created for team-mates or even own movements. The coordination between the wing-backs – especially Gonzalez – and the position on the 8 (e.g. Forster or Klement) was exemplary (figure 6).

A further aspect in the improved balance between risk-taking and covering of own attacks relates to the timing when to move together to position well for counter-pressing. This improved timing came along with better decision-making in the general build-up. Over time, with some up and downs before, VfB showed great improvement in the critical decision when to play the vertical, often risky, pass and when to keep circulating the ball.

Finally, in the new 3-4-2-1 – formation the roles of the individual players were more appropriate for their profiles. For a long period of time, Silas occupied positions or at least appeared frequently in half spaces in rather tight situations with many surrounding opponents. For instance, in the game against Hamburg you could observe many of such situations in which he was given the ball with little space and hence time to start an action. Moreover, he was then often positioned with his back to the offensive zones. Silas can thrill when he has space and can move towards the goal with open vison. Confronted with one or more defenders he can use his dynamic to pass by or serve the ball to team mates after attracting the attention of several defenders. In contrast, his strengths come not to shine when he receives the ball in rather tiny spaces in central zones. Given his relative great size (1.89m vs. Gonzalez: 1.80m), Silas cannot use his strength when he has his back to the opponent´s goal to the maximum. In such situations he is not the best in freeing himself under pressure. Then he rather plays the ball back to team-mates in the first line who can get under pressure if the opponents – already in motion – move up and cover Silas with their cover shadow. In his player attributes, Silas resembles to some extent Frankfurt’s Kostic. The Croatia is also a player who likes to attack from wider zones and can thrill once he has picked up speed. In rather tight situation in which he cannot even get the ball under control, he cannot leverage his dynamic. From a team-standpoint, all of this makes not much sense as you can only lose by getting under pressure from the opponents and allowing transitions.

Moves in the half-spaces or more crowded areas fit much better to the Argentinian Gonzalez. With his technical touch and his lower body centre of gravity, he is more skilful concerning quick unexpected moves with the vision away from the open field. Such differentiations how players perform with their back to the opponent goal versus situations with an open field of vision between play for instance a critical step when Julian Nagelsmann from RB Leipzig assesses players.

Thus overall, Silas’s shift and focus on wider zones was one out of some changes. It was an important move. Together with adaptions in the new 3-4-2-1, it did not just allow him to leverage his strengths, but also created several advantageous positions for the entire team.

3) More on transitions and the play against the ball

So far, we have focused mainly on the game phase with ball possession. In some respect we already touched on the play against the ball when it comes to transitioning after ball losses. As pointed out, Matarazzo’s VfB does lay an emphasis on immediately winning the ball after ball losses through counter-pressing – mechanisms. The coach focused on optimizing structures in own ball-possession to win the ball back and limit the opponent’s opportunities for counter attacks. Thus, the focus was clearly put on limiting the potential danger. Winning the ball back for own promising counter-attacks after successful counter-pressing was rather a side issue. Hence, the work on actions and collective pattern for the moment after ball wins was not as carefully prepared as the actions to win the ball in the first place. This is not to say that VfB did not do a good job here. Instead it was rather a question of objectives and the time available.

First, from a strategic standpoint winning the ball back after transitioning helps limiting the risks of opponent’s counter attacks and might bring the team itself in a promising situation to create a chance. Hence, it is logically to set the first step before the second and focus on winning the ball. Second, the VfB has players with profiles that help to exploit rooms and unsorted opponents in rather unstructured and opaque game situations. Naturally, the ball wins have too prepared in the first place. However, starting and finishing an own counter then can only be practised to a certain extent. A good current example is Borussia Dortmund or Bayern Munich. They prepare and enforce situations which can lead to counter-pressing opportunities. They consciously play vertical passes from midfield in higher zones. Several players move towards the ball and position around the ball. Hence, they can use the advantage of their dynamic against the opponent players. Specifically, they can exploit such benefit after lay-offs of the pass receiver. Alternatively, in case the ball bounces off in the space or to opponents they can leverage their started runs for counter-pressing.

Thus, Stuttgart focuses on enforcing the ball wins in the first place. What happens after is on the one side more a question of variability and creativity of the own players. On the other side, one can guide such promising ball winnings. The exact movements can be prepared with certain principles. Nonetheless the room for variations is here wider in comparison to the game phase with a deep build-up. Tactically, VfB’s focus at this point is put merely moving the ball as quickly as possible away from the narrow space and in the best case to a player with an open field of vision for vertical pass lines.

A third factor was the Corona-break. During this time possibilities for sessions with the entire team as well as exercises with direct player contact in tackles was limited. Presumably, during this time the VfB has worked on collective positioning in the build-up and for possible counter-pressing.

As indicated above the play against the ball during oppositional build-up did not attain as much focus as the phases of own ball possession and transitions. Naturally the VfB was in the role of expected to win the game. Therefore, in many games against underdogs the VfB was the team more eager to create chances. While the play against the ball did not play as much of a role then, it is important to consider in the future. One can expect that in the Bundesliga in the upcoming season this game phase will take a more important role.

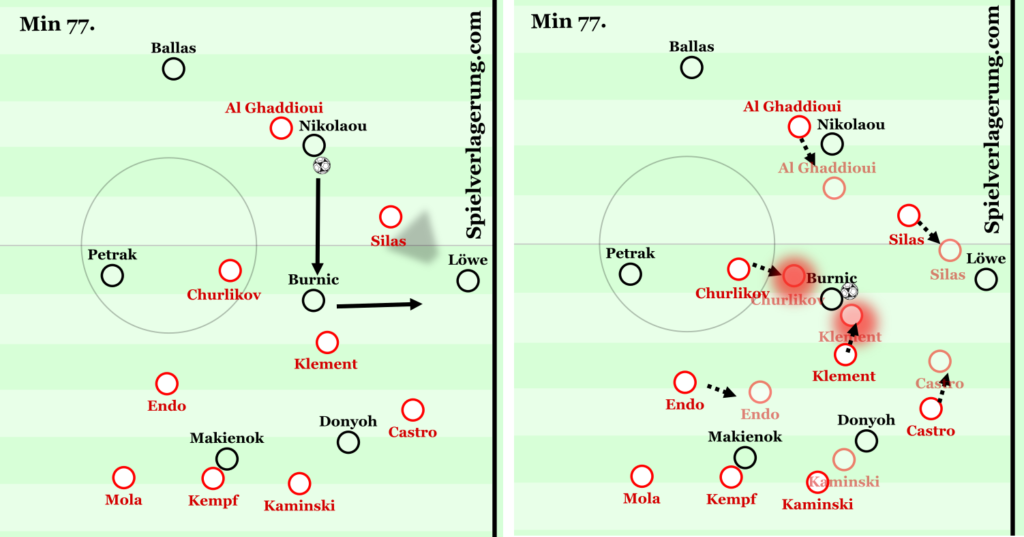

Up to this point in time, the VfB showed most often a solid structure and movements against the oppositional build-up. The VfB either focused on guiding the opponent to their wingbacks to simply close the options, create pressure and force the opponent to play back to the central defender. In some games the VfB-offensive tried to leave the passing lanes in the centre open. Once the oppositional midfield players on the 6- or 8-position dropped to receive the ball, the VfB followed them individually and covered them man-based. For instance, Mangala or Endo moved forwards. Overall, the play against the ball appeared stable but showed a certain vulnerability through too passive behaviour. One example below (see figure 8). Dresden could easily move the ball through their play over Burnic to Lowe. The latter has much room and low pressure. While this is not a very dangerous situation yet for VfB overall, it generally symbolizes the occasional lack of collective moments and positional adaptions.

There is definitely more room to use such situations to enforce ball winnings. One means could be pressing traps. It is unlikely though that we will see this sometime soon in the next season. The opponents will be of greater quality and be able to deal with such possible traps probably better than teams in the second division. And as this phase of the game is not the main strength of the VfB, it probably makes sense to be solid here, and focus on the mentioned attributes in build-up, counter-pressing and transitions.

Conclusion

VfB succeeded by finishing 2nd place and winning the race for promotion against Hamburg. Matarrazo’s VfB laid a focus on dominating the games in all phases. This involves the emphasis on build-up and creating proactive structures for anticipating counter-pressing moments. Here, a constant point of attention was the balance between risk-taking with the ball and constraining danger for opponent’s counter attacks. It is work in progress that has shown a clear positive trend towards the end of the season. Hence, one can be excited to see how these developments play out over the summer and will turn out in Matarazzo’s first Bundesliga season as head coach.

Writing by Tobias Meyer; Editing by Constantin Eckner.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen