The Misery of Bayern Munich

Niko Kovac revealed the whole dilemma in a press conference a few days ago. Asked whether Bayern Munich could play a similar pressing to Liverpool FC, he verbally blocked the line of inquiry. One would have to have the right kind of players for that, he said. He would need more time, too—perhaps even the full four years Jürgen Klopp has already spent in Liverpool. For the head coach of ultra-ambitious Bayern, this was a meagre statement and a symbol for the current situation.

We need not kid ourselves: Bayern will probably once again be German champions this season. That is not due to their brilliance, rather the mediocrity of their immediate competitors, who are mostly dealing with their own problems instead of hunting down the Bavarians. Still, few in Munich are content. Because they know that, come springtime, they will once again be in for a rude awakening should Bayern advance to the quarter- or semi-finals of the Champions League.

At the moment, the misery is not singularly being laid at the feet of Kovac. Still, the head coach, who has been wounded and is often left alone by the club’s upper management, defends himself for quite some time now. His somewhat disrespectful statements toward the team seem to be a part of that. Asked about Liverpool’s football, he said: “You cannot try to go 200 kilometres per hour on the Autobahn when you can only manage 100.” Maybe he wanted to underline that his players, on average, lack speed, which, however, seems somewhat far-fetched given his quick attackers. Perhaps he wanted to convey subtly that Bayern cannot keep up with the Mo Salahs and Sadio Manés of the football world.

From his point of view, this broadside would even make sense, because lately Kovac could only truly rely on Robert Lewandowski and Serge Gnabry, while the mediocre performances of his other players often had him furrow his brow. However, Kovac cannot deflect all the responsibility in this situation. Of course, the squad is still in a state of upheaval. And he does not have all the players he wished for—Leroy Sané, for instance—at his disposal. The sporting misery is also down to Kovac, though.

No control over the pitch

This starts all the way back with the uninspired possession play and ends up front with rudimentary pressing. Few things in-between the two extremes work well, either. The counter-pressing, for instance, is not working well, as Kovac tried to convey to the public, but rather a weakness of this team. A weakness, that has robbed Bayern of their once so striking defensive stability.

Of course, they are still one of the best defensive sides of the league going by important statistical indicators such as the PPDA. But they no longer look down on the rest of the field from a high throne. Last season already, opponents had a realistic opportunity to come back after going behind against Bayern. Outside of Borussia Dortmund, this used to be an unthinkable idea for Bundesliga teams a few years ago.

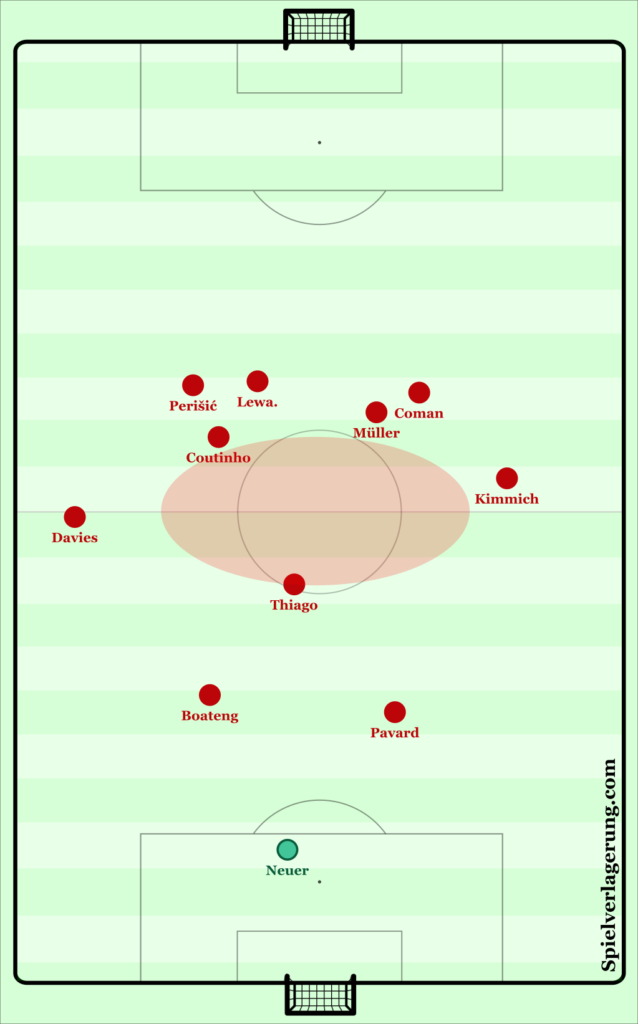

The point of origin of all the malady lies within the weak formational structure of Bayern who, especially under Kovac, fail to properly man the centre of the pitch. Just a few weeks ago, the two central midfielders remained in their deep position and only insufficiently joined in the attacking play. Kovac then switched from a 4-2-3-1 to a 4-3-3 and managed to create an inverted effect. Now the two more offensive-minded midfielders are staying too far up the pitch and, quite regularly, too far toward the wings as well. They do not support the build-up play sufficiently.

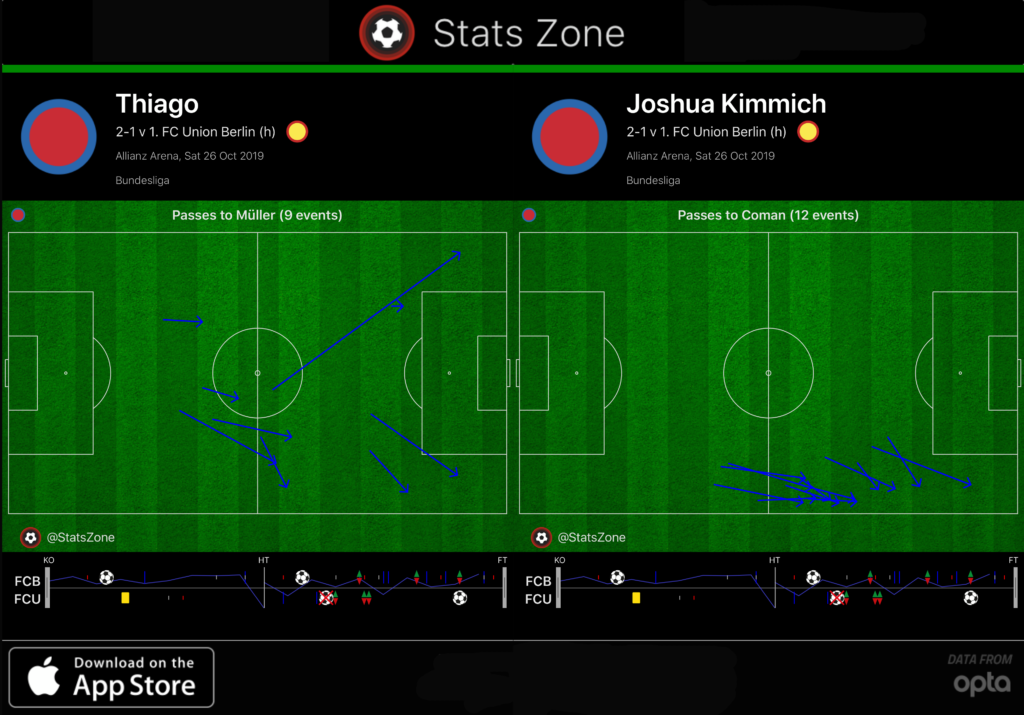

The statistical values of recent games underline this aspect, as the number of passed played between the central players in comparison to those on the wings clearly shows how often the build-up play is being kept out of the centre and how Bayern try to find a way on the flanks. Of course, they have an advantage in individual quality over many opponents there thanks to Gnabry, Kingsley Coman and others. But when the penalty box and the zone 14 are well covered, Bayern’s wingers do not have the option to forge ahead from the wing into the centre. This results in a lot of crosses and chipped passes from the half-space.

It is this generally weak occupation of the pitch which results in a possessional play that the opponent can relatively easily guide toward the flanks. It also results in bad counter-pressing because of a lack of compactness in close proximity to the ball, which is why Bayern can no longer develop their intrinsic dominance in possession of the ball.

Where is Pep Guardiola?

In this context, the question comes up again and again when and why Bayern have gone through this negative development. And why the erstwhile developments under Pep Guardiola have been reversed. During his time at the club from 2013 to 2016, Bayern may not have won an international trophy, but they were so compact in proximity to the ball that their (ostensibly) ultra-attacking playing style did not come back to hurt them. Their counter-pressing failed to work only against absolute top teams at the most. Other than that, the team exuded an overwhelming dominance which left many opponents no room for air especially in transitional situations.

However, it seemed that, after the Guardiola era, Bayern moved away from this footballing philosophy because it was not Bayern-like enough and because they failed to win the Champions League under the Catalan. Bayern did not, though, perform a true paradigm shift and were now standing in a grey area of the vague. The absolute will of a philosophical upheaval toward a more high-octane football—without having the suitable components, such as the right coach, for it—has turned Bayern to a second-rate team, at least in the international context.

The upheaval in the squad, which had been discussed and least partly advertised for years, did not force the club into throwing over board the playing philosophy of its successful period. However, Bayern are still stuck in a notional contrariness just as other parts of German football: On one hand, they want to be trailblazers in Europe, for example to overcome the financial differences—and the pressing era under Klopp, Jupp Heynckes and others was a perfect time for that. On the other hand, there seems to still be a longing for a genuinely German or Bavarian brand of football, even though this line of thought is still being coined by the era around the year 1990.

Their football is supposed to be fast yet at the same time tactically sophisticated and, ideally, successful even when the club does not go for the best players on the transfer market. And it is supposed to be represented by a coach who distinguishes himself through strong leadership, eloquence and a certain approachability. Essentially, Kovac can really only lose here—despite all his own mistakes in the last few weeks and months.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Ryan September 22, 2020 um 2:29 pm

I do wonder if this would be revisited now that Flick has shown it can be done with the same players🤔