The State of the Bundesliga Title Race

Three of the five major European leagues have had to endure the dominance of a single club in recent years, including the Bundesliga. Since Dortmund’s heyday under Jürgen Klopp, Bayern Munich has won the championship seven times in a row. But this season everything may be different.

There are great doubts about the current Bayern team, which were able to snatch the championship from BVB last season despite some glaring shortcomings. During the summer, they then tried to sign a few star players on the transfer market, but failed until the emergency loans of Ivan Perisic and Philippe Coutinho. The current team has nevertheless been upgraded. With the signings of world champions Lucas Hernández and Benjamin Pavard already before the opening of the transfer window, the defence has been enhanced significantly. That said, the feeling remains that the tactically limited football of coach Niko Kovac cannot fully exploit the potential of this still highly talented team.

So is Borussia Dortmund’s time upon us? Perhaps. Immediately after the end of last season, the club hit the headlines because they signed several top-class players: Julian Brandt, Thorgan Hazard, Nico Schulz and a little later Mats Hummels. The already strong squad has thus reached a level that at least in terms of squad depth can compete with Bayern’s. But similar to their big rivals from Munich, Dortmund’s coach is far from undisputed. Lucien Favre has proven that he is able to elevate a team to a high level and keep it there, but is he good enough for a championship winning season?

RB Leipzig, on the other hand, has the greatest trainer talent among the top teams in Germany. The up-and-coming club from the east of the country had already secured the services of Julian Nagelsmann some time ago. With his outstanding performance in Hoffenheim over a couple of seasons, the 32-year-old ensured that he has quickly become a well-known name in international football. In addition, he prefers a footballing approach that differs from the classic Red Bull style. And the first few matchdays have shown that this season could be more of a three-way fight than a duel for the championship.

Why do Bayern seem stuck?

In the second half of last season, Kovac decided to adapt his system a little after some mixed performances going into 2019. The change from a 4-3-3 to a 4-2-3-1 brought more presence in attacking zones, because Thomas Müller did not act as a classic no. 10 but as a kind of secondary striker. He orbited Robert Lewandowski in a similar way Antoine Griezmann does with his teammate up front, although Müller still lives far more than the Frenchman from runs behind the defence.

Lewandowski benefited from this change, as he now had another player around him to interact with. Lewandowski was often the target player in Bayern’s early build-up. The ball reached the Pole, who then tried either the fast layoff or the diagonal pass through the backline. Many plays relied on Lewandowski—as they do this season, which is both a curse and a blessing. For Bayern it is of course outstanding that they have such a top striker in their squad, but it also underlines their penchant for hero football, which leads less to success through collective interaction and much more through the quality of individual players. If an opponent can effectively neutralise Lewandowski, the Bavarians are considerably weakened because they then lack the offensive playmaker.

Now these are all problems that can be solved. A few small tactical adjustments and the team would be more dynamic and less predictable. Even if they take more risks, the counter-pressing is so stable that the ball is quickly regained. However, Kovac hasn’t proved yet that he can really develop these ideas. And the fact that he, to the astonishment of many, recently stated that tactical changes are just difficult to make during a game doesn’t help his position in the current situation.

Are BVB the real deal?

Meanwhile, the Dortmund team already had to cope with setbacks. Particularly, the 3-1 loss against the blatant outsiders Union Berlin came as a huge surprise. The subsequent excellent performances against Bayer Leverkusen and FC Barcelona then confirmed one assumption: BVB shine if the games are characterised by a certain wildness and many moments of changes of possession. Then the necessary space is created for the attacking players, who have exceptional control of the ball and good instincts at high speed.

However, in the Bundesliga the BVB will seldom have an open matchup. Many opponents attack with long balls Dortmund’s central defence, which has its strengths in defending around the penalty area rather than in the open field. Hummels, for example, benefits above all from his positional play and his timing when tackling, but the former German international is not a good sprinter by any means. In addition, the support for the defence after long possession phases is often inadequate. Dortmund do not always secure their possession of the ball and overload the last third without paying attention to the necessary adjustments in order to be able to counterpress in case the ball gets lost.

Favre does not seem to be an excellent ball possession coach in general. Strategically, he has a good understanding of how to create scoring chances, as his team usually assess their shooting positions very intelligently and do not waste attacks on unnecessary attempts. But to be able to reach those positions in the first place, BVB need more than the Favre-typical narrow midfield line and the deep press in their penalty area.

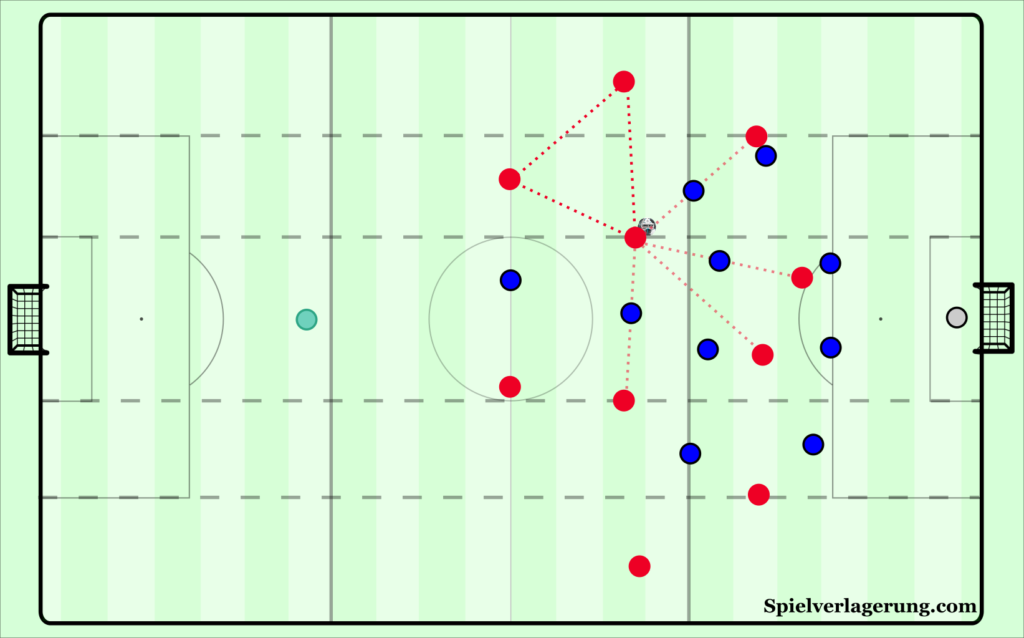

Long counter attacking situations can lead to goals. But against Leverkusen and Barcelona it was striking how difficult it was for Paco Alcácer and company to beat seasoned defensive players on a 50-metre long section of the field with only two or three players. The best BVB attacks are created when the four attacking players are positioned between the opponents’ lines while from behind the two full-backs bring unrest into the opponents’ formation with great dynamism. BVB have the quality on all positions to break through man-oriented defensive schemes. Once an opponent has been beaten, a domino effect unfolds because every Dortmund player keeps the dynamics of the attack alive and does not have to stop and interrupt the flow of the play.

Favre doesn’t have to work on this aspect. Instead, he should rethink certain structures in the build-up. Hummels has become a strong pivot on the left side. With Julian Weigl, Favre actually has a second talented ball possession specialist, who likes to play on the right side of the central midfield and thus could be the counterpart to Hummels. But at the moment the rather defensive-minded Thomas Delaney seems to be ahead of Weigl in the pecking order.

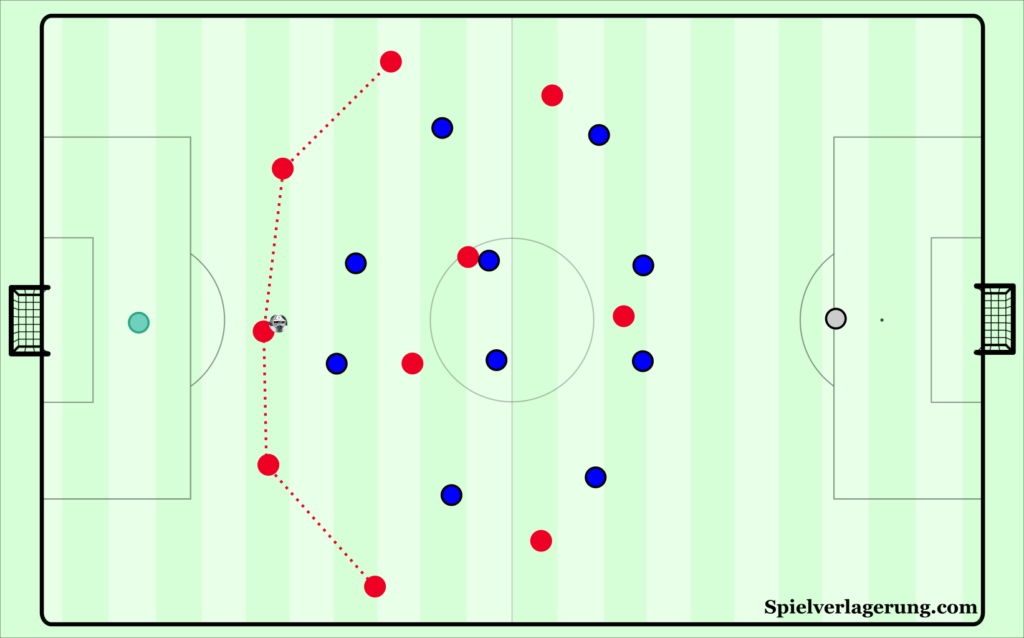

What should be concerning about Dortmund’s build-up is how easily some opponents can completely shut down the black-and-yellows by employing a man-marking scheme. Frankfurt, for instance, did just that on Sunday when they mirrored Dortmund’s formation. BVB have a tendency of cutting the formation in two, with the front four being somewhat isolated from the deep hexagon which let the ball circulate early on in the build-up. Usually, Hummels or one of the centre-midfielders intends to play the ball through the half space down the field. But since then the receiver is more or less isolated and doesn’t have many passing options to continue the play, opponents can push Dortmund back.

Because of how the build-up is set up, BVB cannot establish dominance over the course of an entire match. The possession game is just not strong enough, and the passive 4-4-2 defence scheme allows opponents to stay alive and keep games open. In order to win the championship, Dortmund should be able obliterate teams occasionally and have an easy matchday.

What are Leipzig up to?

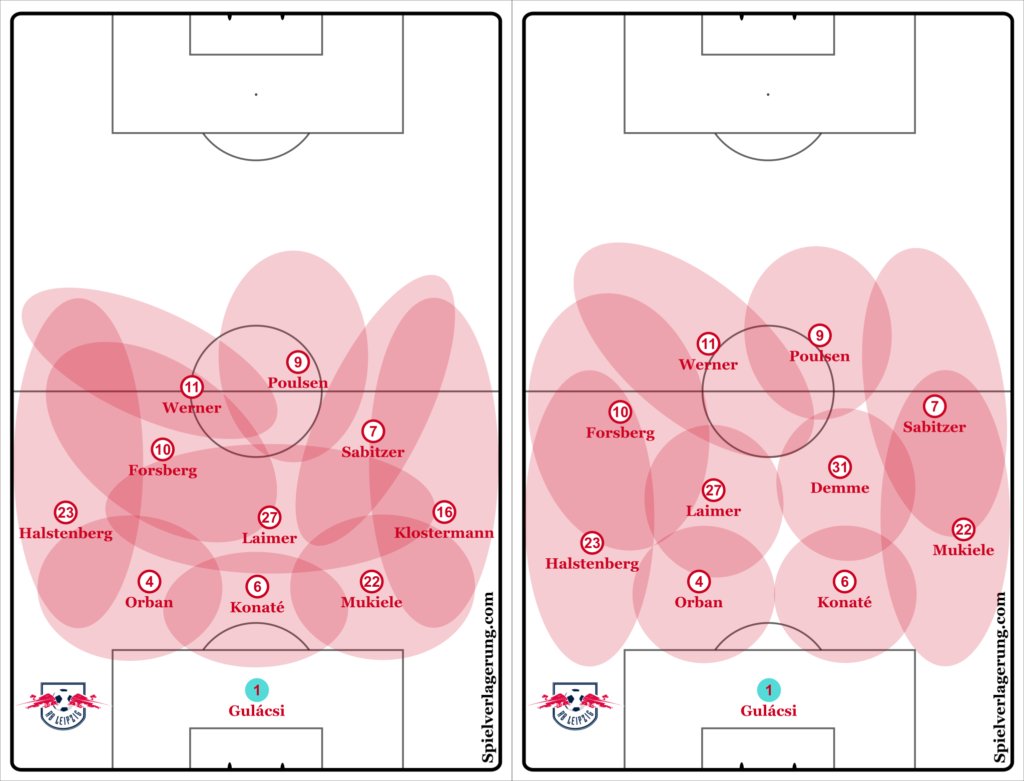

Within a few weeks, Nagelsmann has established the idea that his team can be successful in two quite different basic formations. First, he started the season with the 3-3-2-2 we know from his Hoffenheim days, which gives Leipzig some variability in midfield. In addition to a strong holding midfielder, Nagelsmann can rely on two attacking players such as Emil Forsberg and Marcel Sabitzer, who then move into the outer lanes during attacks or into the central hole behind the two strikers. But he can also let a hybrid player like Christopher Nkunku or Kevin Kampl play in the half-space and thus strengthen one of the two wings in Leipzig’s structure and better secure the full-backs who both advance high up the pitch quite quickly.

At the beginning of the season, the 3-3-2-2 worked well, although Nagelsmann was still experimenting with personnel. At the same time, Leipzig’s new coach had a 4-4-2 in mind. In the last few years, the Leipzig team often played with two inverted wingers or two no. 10s, as some coaches called it, in a 4-2-2-2. Under Nagelsmann, however, Forsberg and Sabitzer are a little further on the outside in his formation, whereby Timo Werner in particular rarely drifts to the left, which he often does in the 3-3-2-2 and which motivates Forsberg to take a more central position.

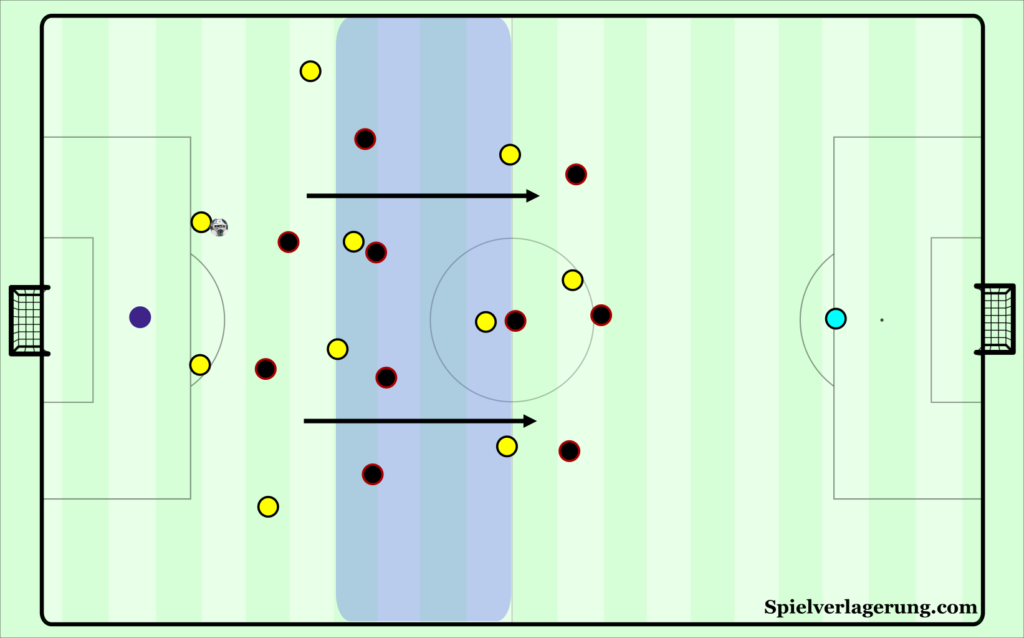

The 4-4-2 also has the advantage that the midfield centre is secured quite simply. Simplicity is not always an advantage, but Leipzig has such a high athletic level that a simply structured 4-4-2 can be adequate to win many matches. During their match against Bayern, the 4-4-2 against fresh opponents might have been enough to control them in many one-on-one duels all over the field. Nagelsmann, however, opted for a 3-3-2-2 to defend Lewandowski’s runs into the midfield with a back three, as one defender was always allowed to move forward without fearing he would open up the backline too much.

But a 3-3-2-2 against a formation like Bayern’s requires a lot of attention and perfect coordination, because there are no natural man-to-man schemes. Within the formation, the players have to shift and switch positions a lot. If, for example, the opposing full-back and winger play down the side and attack Leipzig’s sole wing-back, he needs additional support. Does he get it from the nearby striker, the central midfielder or from the back line? Questions like these arise endless times during the game and must always be answered correctly.

Due to their athleticism, Leipzig could choose the easy way and gradually wear down opponents over the course of 90 minutes in plenty of one-on-one situations. But this is not Nagelsmann’s strategy, because he knows that during the season his team may tire and not every opponent will be athletically inferior by a wide margin.

Moreover, Leipzig’s new head coach seems adamant about conserving his teams energy and not empty the gas tank too quickly. Once the club was famous for high-octane pressing, but under Nagelsmann Leipzig are more thoughtful when defending against opponents who are building up. The 3-3-2-2 then easily becomes a 5-3-2 with only two players higher up the pitch and some man-marking in midfield while the offside line is protected with a tight defence the covers the passing gaps quite effectively. Nagelsmann’s current path with multiple systems and more conservative pressing schemes leads him to work towards constancy and long-term success.

Where does this leave us?

All three teams embody interesting aspects of the game: Bayern have the quality, Dortmund the attacking power and Leipzig the athleticism as well as a lot of potential. None of the three teams, however, looks as if they are now tearing the competition apart week after week. Instead, a close title race with close matches against midfield teams could develop. This in turn challenges the coaches, who cannot just be reactive or passive, but also have to tackle the tasks with a wealth of ideas. That’s why Kovac, Favre and Nagelsmann are even more in the limelight than usually.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen