Potter’s Swansea Hold Bielsa’s Leeds

Swansea City hosted Leeds United on Tuesday evening in what was set to be a very appealing match-up between two of the best managers in the Championship. Both sides came into the game unbeaten. Graham Potter has revitalised the Welsh side that was relegated from the Premier League last season, following on from a fantastic spell as manager of Swedish club Östersunds FK, guiding them to the Europa League Round of 32 last  campaign. Leeds on the other hand have perhaps been the most impressive team in the Championship so far this season, playing an attractive style of possession-based attacking football under Marcelo Bielsa that has rarely been seen in England’s second division. Leeds convincingly won their first three matches of the season, with this match at the Liberty Stadium set to be their toughest challenge yet.

campaign. Leeds on the other hand have perhaps been the most impressive team in the Championship so far this season, playing an attractive style of possession-based attacking football under Marcelo Bielsa that has rarely been seen in England’s second division. Leeds convincingly won their first three matches of the season, with this match at the Liberty Stadium set to be their toughest challenge yet.

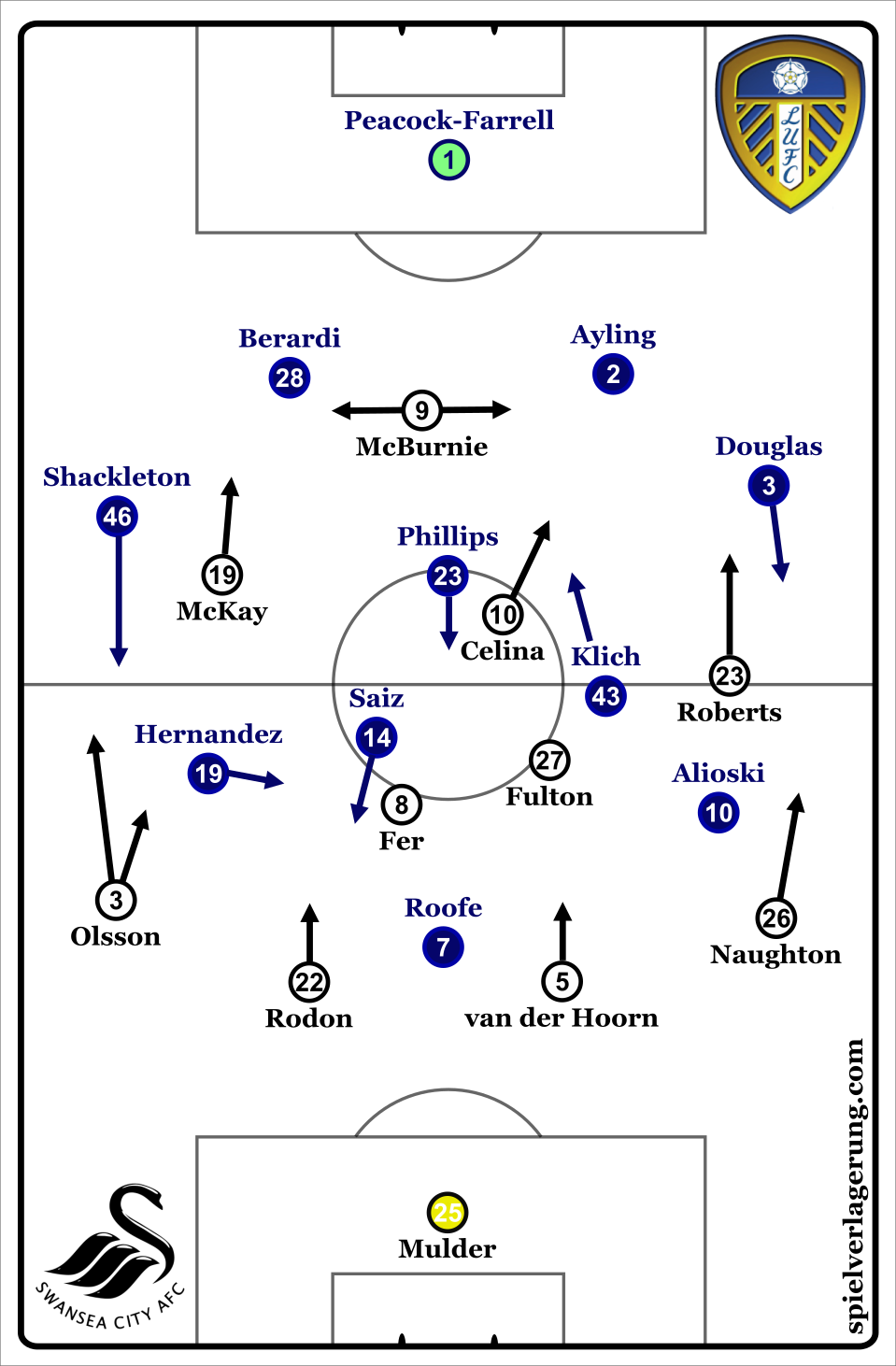

Both teams started with familiar line-ups. Connor Roberts was deployed in a right-midfield position after impressing against Birmingham last Friday, whereas Leeds were forced into starting eighteen-year-old Jamie Shackleton at right-back after Liam Cooper was injured during the warm-up.

Swansea’s Energetic Start, Leeds’ Problems

Kemar Roofe routinely pressed Swansea’s centre-backs with the support of one winger. When the ball was moved to a wide position and then circulated back inside, Hernandez or Alioski would move from directly marking the ball-near full-back to marking them in their cover shadow by using curved pressing runs to close down the nearest centre-back. By eliminating the full-backs as a short passing option, Hernandez and Alioski directed the centre-backs toward the middle of the pitch, where Leeds’ central-midfielders were tightly man-marking their opposing counterparts, meaning there wasn’t a free man to pass to.

Hernandez (#19) curves his pressing run too wide, meaning he is unable to prevent Rodon (#22) from dribbling forward. Saiz (#14) and Phillips (#23) are reluctant to leave their marking assignments, meaning Rodon can continue to dribble through and beyond Leeds’ midfield.

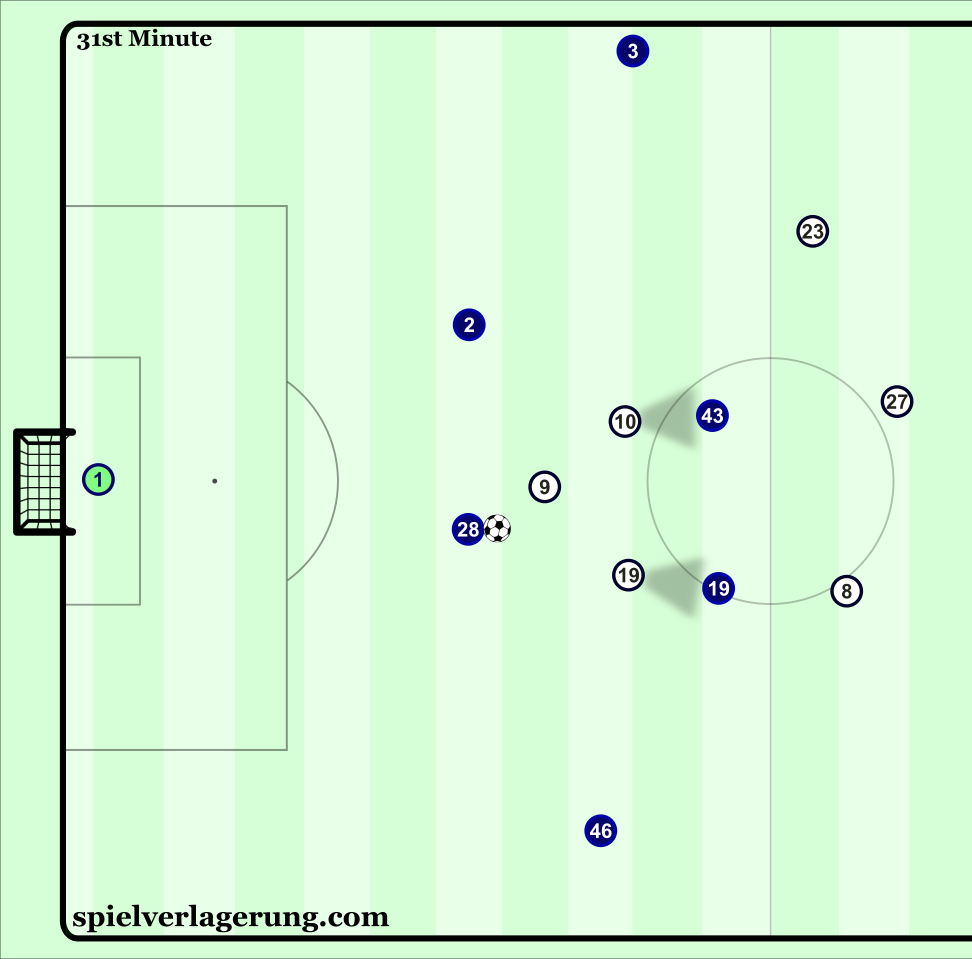

However, instead of van der Hoorn or Rodon being forced into playing long balls forward by Leeds’ pressing, Hernandez and Alisoki’s pressing runs were curved too wide, which left space in the middle of the pitch to dribble into. By aggressively dribbling out of the defensive line and into midfield, Leeds’ central-midfielders had to either leave their man-marking assignment to close the player on the ball down (thereby leaving their previous marking assignment as a free man), or if they chose to continue their marking responsibility, the centre-back could continue to dribble through the midfield and into the more attacking phases of the pitch.

This appeared to be a recognised weakness of Leeds’ 4-1-4-1 pressing scheme by Potter. As Roofe was the only player in the middle of the pitch who was able to press Swansea’s centre-backs (as Leeds’ central-midfielders had no access due to their man-marking assignments), van der Hoorn and Rodon could continue to dribble as they were repeatedly in a 2 v 1 situation against Roofe. Moreover, by aggressively dribbling out of the defensive line, Roofe was unable to backwards press due to the speed of the action. On one particular occasion, van der Hoorn remained in an attacking position after dribbling through Leeds’ midfield, and by occupying the attention of opposing central-defenders in the penalty area, McBurnie was left with more space to score Swansea’s second goal.

Swansea posed their biggest threat to Leeds in attacking transition, where intense overlaps from Naughton and Olsson repeatedly allowed progression through the wings and resulting crossing opportunities. Olsson would seldom make underlapping runs when McKay moved toward the touchline.

McBurnie tended to roam away from Leeds’ defensive line, which either Ayling or Berardi tightly followed. This created space in the defensive line to advance if McBurnie was able to receive and use his physical presence to turn past this pressure. Consequently, the ball-near full-back was forced into closing McBurnie down, leaving the winger (that the full-back would have been marking if the centre-back wasn’t out of position from following McBurnie) open in space to advance in behind the defensive line.

McBurnie’s defensive work rate also makes him valuable when Swansea don’t have possession. He was supported by McKay and Celina in pressing Leeds when they played out of defence from the goalkeeper. This three-man chain remained compact in the middle of the pitch to prevent Phillips (and later Klich), Leeds’ primary route of progression through the centre, from being a short passing option, limiting Leeds’ options to the full-backs for indirect progression. The only scenario where space was available in the middle of the pitch during build-up in the first half came following ball recoveries where Swansea players were out of position.

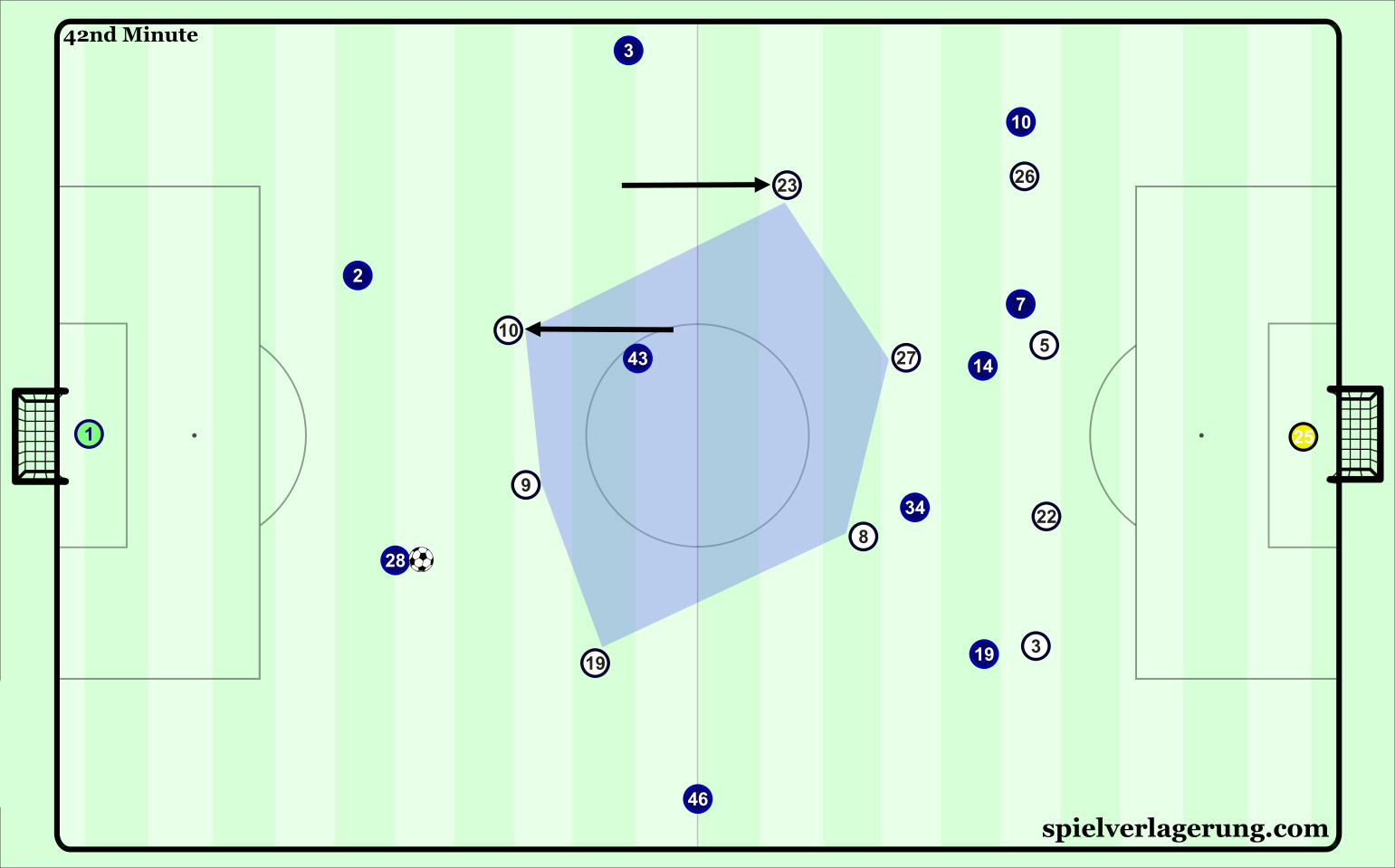

Swansea’s asymmetrical 4-3-3 pressing structure, with Celina (#10) moving into the forward line and Roberts (#23) dropping into the right central-midfield position. There is however a large exploitable space between their forward and midfield lines.

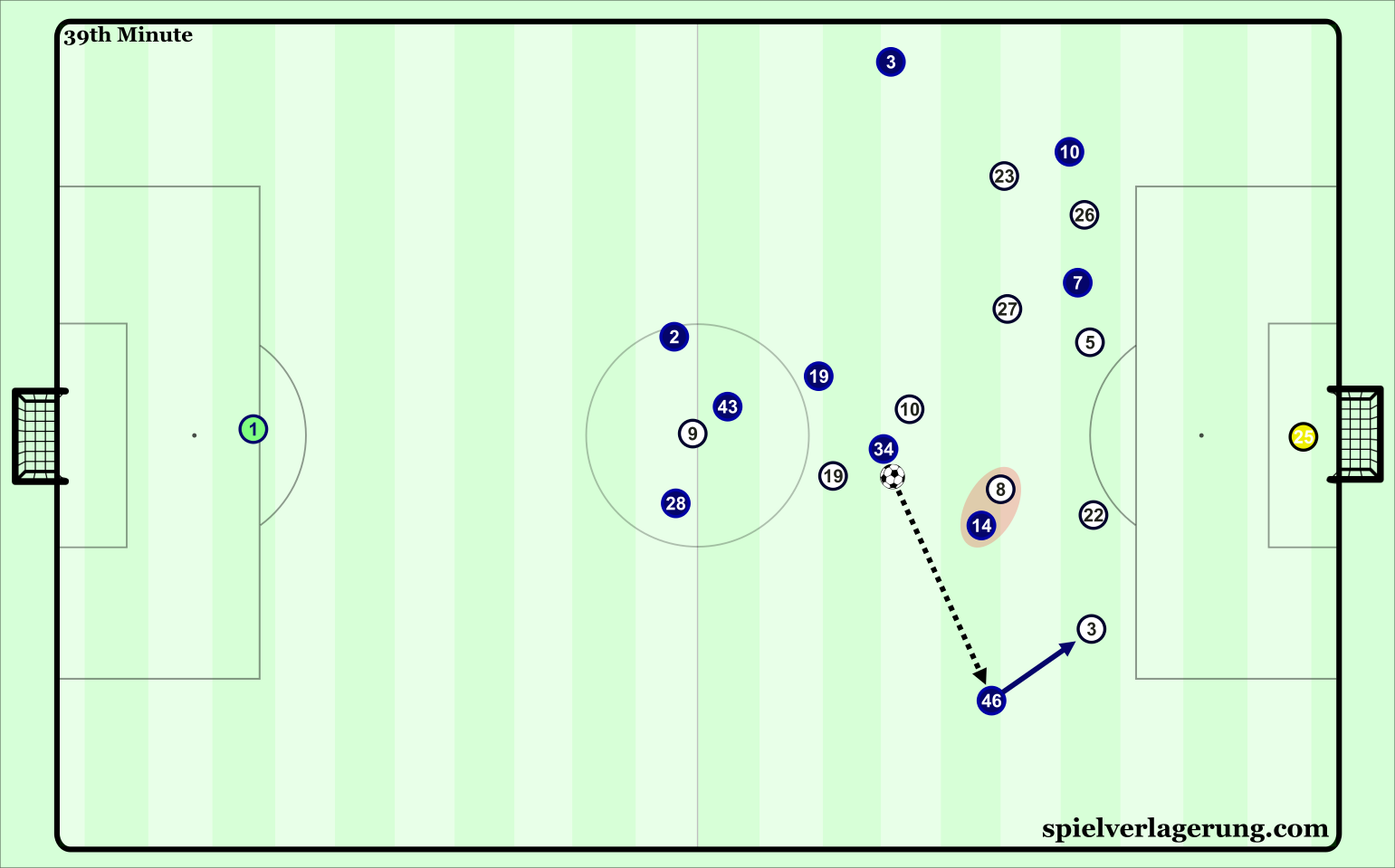

Roberts intermittently remained in a more advanced position to create a four-man chain with Celina, McBurnie and McKay. This lurking pressure and man-to-man marking commonly forced Peacock-Farrell into ushering his defenders up the pitch and to play long goal-kicks. This meant that Leeds struggled to settle into their possession game in the first twenty-five minutes of the match. Their spacing and structure in midfield was almost always sub-optimal (spaces between teammates were too small, lack of staggering in positioning, too many players operating in the same vertical channels etc.), whilst also failing to move Swansea’s 4-4-1-1 mid-block to produce exploitable spaces. This poor midfield dynamic led to a turnover and Swansea’s first goal, where Berardi and Ayling were left completely exposed on the counter-attack because of the central-midfield issues and the full-backs operating very high up the pitch as Leeds’ primary source of width in possession.

The dis-organisation of Leeds’ midfield, in addition to the positions of Douglas (#3) and Shackleton (#46), leave Swansea in a numerically superior situation on the counter-attack, which they eventually convert into the first goal of the match.

It’s extremely difficult to play possession-based football without an appropriate structure to defend in transition (defending with the ball).

The Crucial Change and Subsequent Improvement

Berardi (#28) can’t use Hernandez (#19) or Klich (#43) as a passing option because McKay (#19) and Celina (#10) are using their cover shadows to mark them.

Leeds’ problems culminated in Phillips being replaced by Lewis Baker in the twenty-seventh minute. Phillips really did perform poorly. He was being dribbled past with ease, either because of a lack of mobility or lack of effort, whilst also worsening Leeds’ play in possession. Initially, it seemed that Leeds’ midfielders were unsure who should fill the central space left by Phillips during Leeds’ build-up, with two of Mateusz Klich, Pablo Hernandez, and Lewis Baker operating alongside each other, but this was easily covered by McBurnie and Celina who could mark both players in their cover shadows.

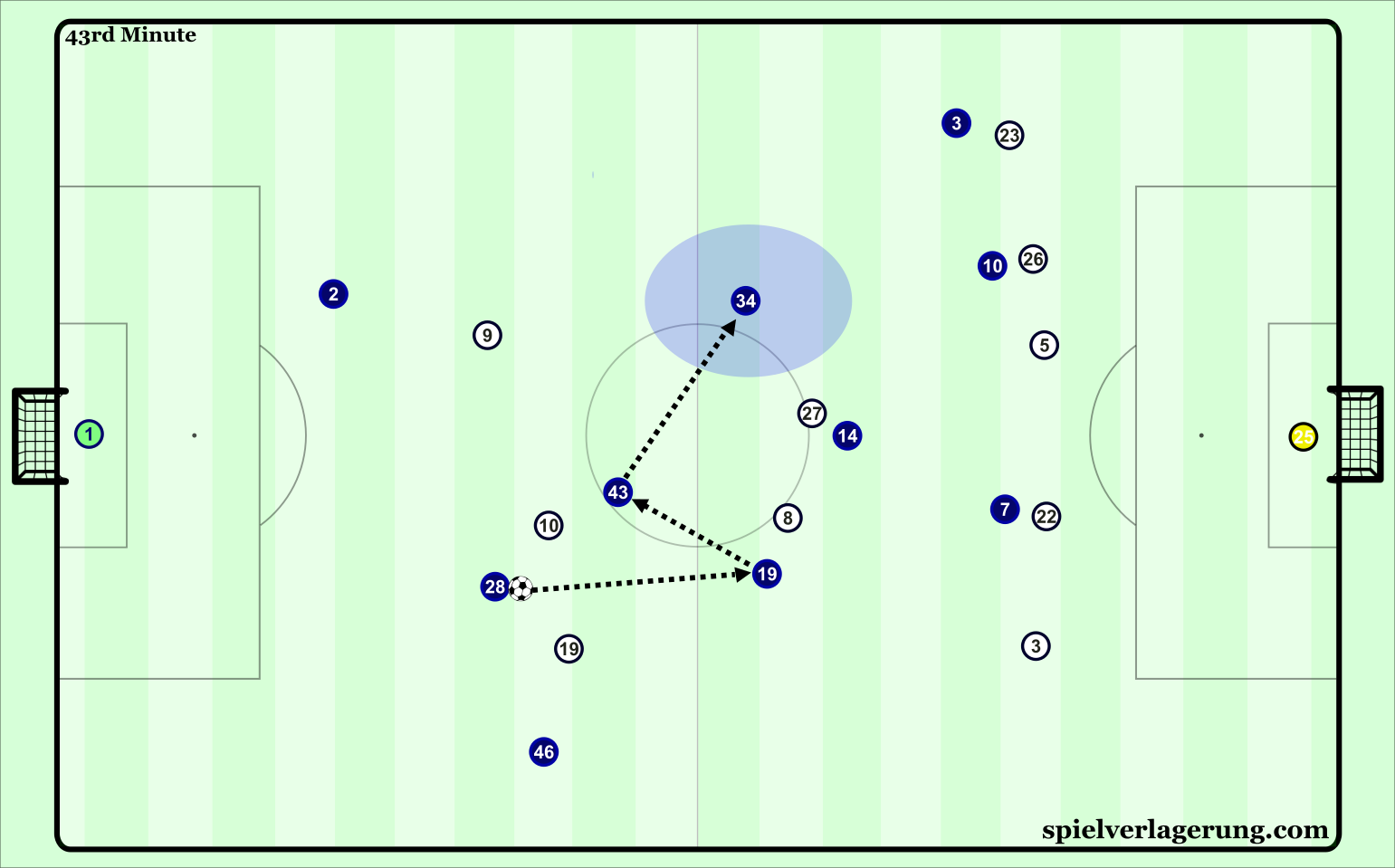

After a word with Bielsa to clear the confusion, Klich was the lone #6, with Baker as an #8 alongside Saiz. From this point, Leeds’ build-up and midfield dynamic was vastly improved. Klich possesses much better game intelligence and positional sense in comparison to Phillips, a big factor in allowing Leeds to play through Swansea’s pressure with greater ease. Hernandez’ role was also now more clearly defined. A winger when defending, but a situational right-sided #6 and #8 in possession depending on the position of his teammates. Instead of not knowing where to operate following Baker’s introduction to the game, when Klich was moved to the #6 position, Hernandez assertively acted as a supporting midfielder to Klich when required after he was moved to the #6 position. His position in the right half-space on the outside of Fer made him a common route for progression through Swansea’s midfield. The substitution of Baker for Phillips was vital for Leeds to gain any kind of foothold and control in the match.

Much improved structure between Swansea’s forward pressing chain and midfield allows Leeds to play through them with relative ease. Leeds outnumber Swansea 4 v 2 in central midfield because Roberts (#23) is being occupied by Douglas (#3) in a more defensive position. Swansea’s right central-midfield position is therefore left vacant, so Baker (#34) is free to receive in this area and advance towards Swansea’s defence through a large area of space.

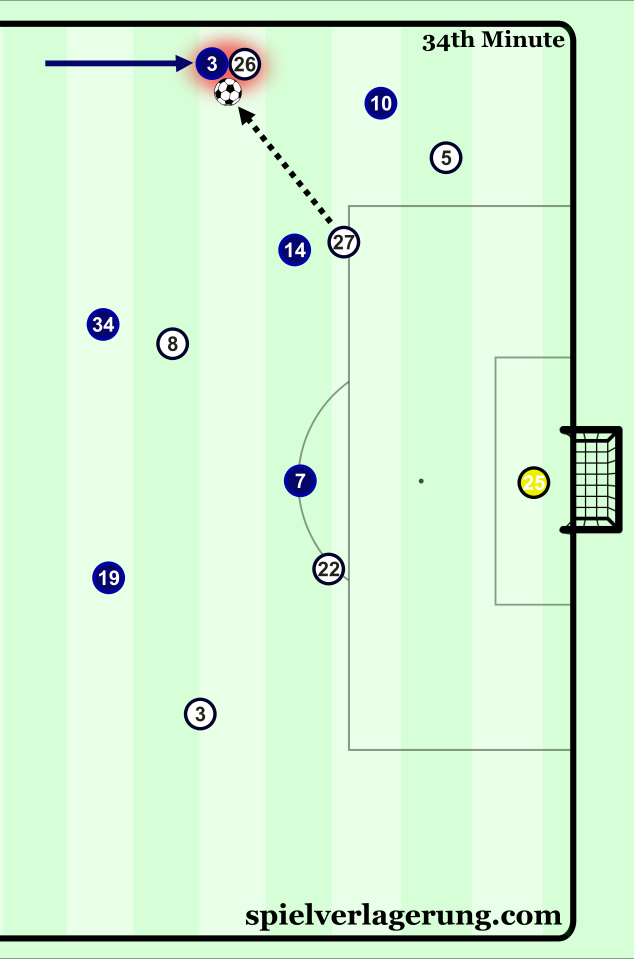

Douglas (#3) presses through Naughton’s (#26) blindside to intercept Fulton’s (#27) pass, winning the ball for Leeds in a threatening area. Swansea’s short passing options are very limited because of Leeds’ man-orientations.

With their midfield finally established, Leeds had a better foundation to build from and grow into the game. Their defensive intensity and aggressiveness increased, sometimes outnumbering Swansea during their build-up (situational 5 v 4 scenarios), thereby forcing errors. As shown in the diagram above, Leeds’ full-backs played an important role in applying defensive pressure high up the pitch, whilst also providing width in possession. This was most effectively used on the right side with Shackleton because of Swansea’s asymmetrical 4-3-3 pressing shape (where the midfield line was skewed towards the right-side of the pitch because of Roberts’ role as the right-sided player in the three-man midfield chain from the right-wing position). Therefore, Fer, on the left side of the midfield chain, was orientated towards Fulton and Roberts on his right to maintain horizontal compactness, which left a large area for Shackleton (much more so than Douglas on the other wing) to exploit on the left side of Fer. His overlapping of Hernandez led to a few situations where he received the ball in a wide area to then dribble diagonally at Olsson, which was how Leeds’ first goal was created.

The occupation of Fer (#8) on the left-side of Swansea’s midfield by Saiz (#14) meant that he had no access to Shackleton (#46) so couldn’t close him down. This left Shackleton in a 1 v 1 situation against Olsson (#3), who is not the strongest defender. Shackleton was therefore able to dribble at then go past Olsson on his outside to cross towards Roofe (#7). The young full-back had an impressive debut, exhibiting good decision-making and composure on the ball.

Whilst largely neutralising Leeds, Swansea couldn’t create any clear-cut chances in the first-half, whereas Roofe’s goal was Leeds’ only high-quality chance of the first forty-five minutes.

Second-Half: Swansea Tire, Leeds Impose

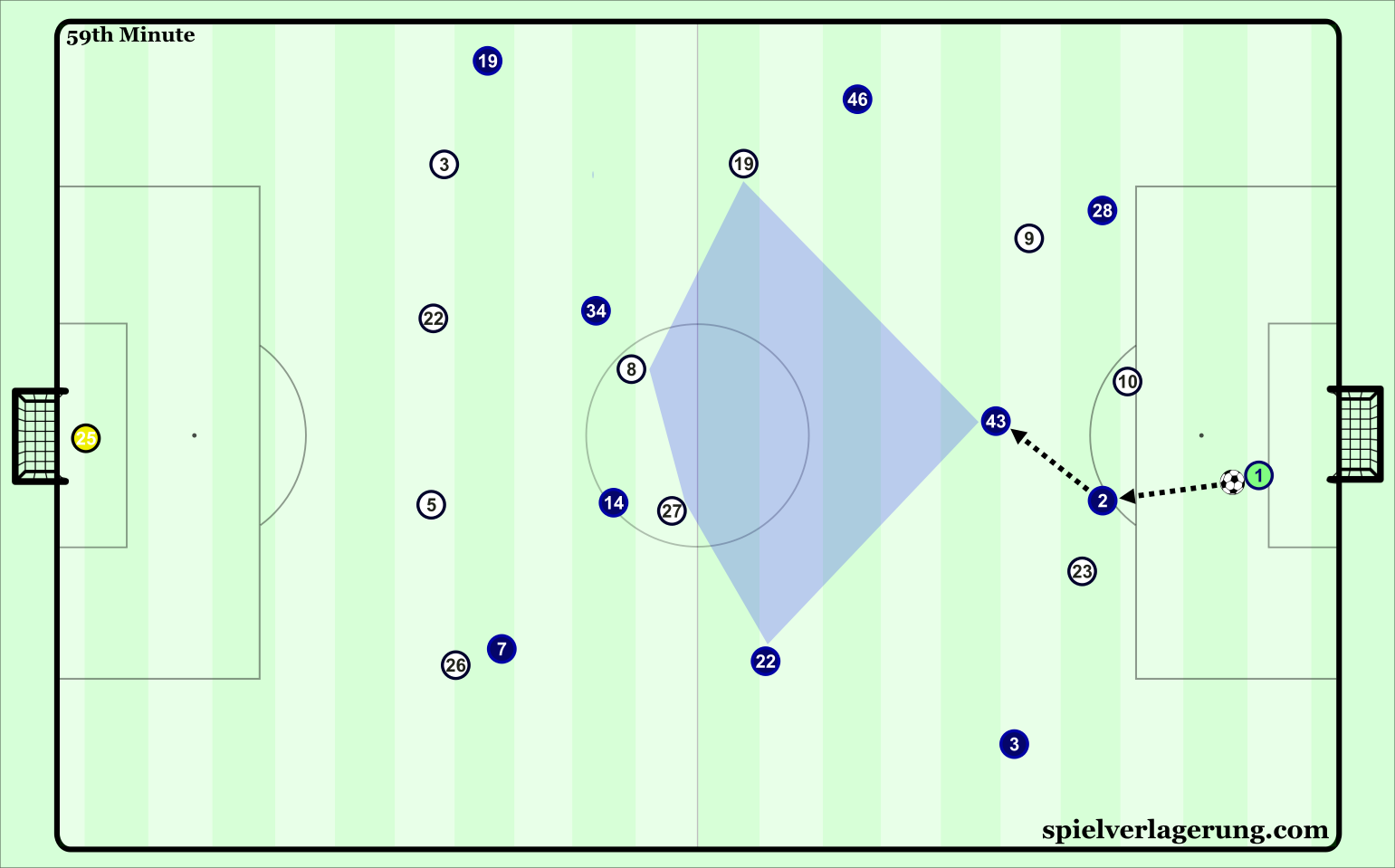

Swansea struggled to maintain their high pressing intensity in the second-half, which heightened the problems that the vertical space between their forward and midfield lines generated. Leeds had improved consistency in building attacking sequences by playing out from their defence as it was easier to play through the space in the middle of the pitch. Klich was often left unmarked and free to receive, turn and dribble with a vast amount of space and time to use before making a decision with the ball.

Leeds are comfortably able to beat Swansea’s initial pressure. The front three’s pressing efforts are becoming lacklustre due to fatigue, and Klich (#43) is able to advance without difficulty through the space between Swansea’s midfield and forwards.

McKay and Celina would sometimes lurk either side of Klich to deter any passes to him, but either Hernandez or Baker would circumstantially drop to provide an alternative passing option in the centre of the pitch. This was achieved with relative ease due to Swansea’s central-midfielders being reluctant to follow as a result of Saiz and Baker’s/Hernandez’ positioning themselves behind them. If they did follow, Swansea’s midfield would no longer be covering the centre of the field effectively and Leeds’ #8’s would have a larger amount of space to utilise and receive passes from their teammates.

Furthermore, if Leeds were forced into playing long balls forward as a result of Swansea’s initial pressure applied by their forward line, it was easy for Leeds to recover the ball if Swansea headed or played the ball straight back towards Leeds’ goal and the space between their forward and midfield lines.

Saiz and Baker/Hernandez were instructed by Bielsa to play much closer to Roofe right from the beginning of the second-half. Saiz was limited by Fer’s standout defensive performance, whereas Baker found better positions in the right half-space behind Fer, Fulton, and later Carroll. He regularly provided an important passing connection between the rest of the team and Shackleton on the right-wing.

Jack Harrison, who was substituted on for Alisoki at half-time, adopted a very narrow defensive position alongside Bamford to either force Swansea to build up via their full-backs or to play long passes forward, whilst also deterring the Swansea centre-backs from continuing to dribble forward into his central position. Douglas would move forward from the left-back area to press Naughton when Harrison was occupying this central position.

Peacock-Farrell commonly moved the defensive line up the pitch as if he was about to take a long goal-kick because of the pressure that Swansea’s forward line posed, but then suddenly a Leeds full-back would drop to create separation from Roberts, thereby creating time and space to play out from the back as opposed to trying to play through Swansea’s pressure in an area closer to their own goal, or by trying to win second balls in central-midfield areas.

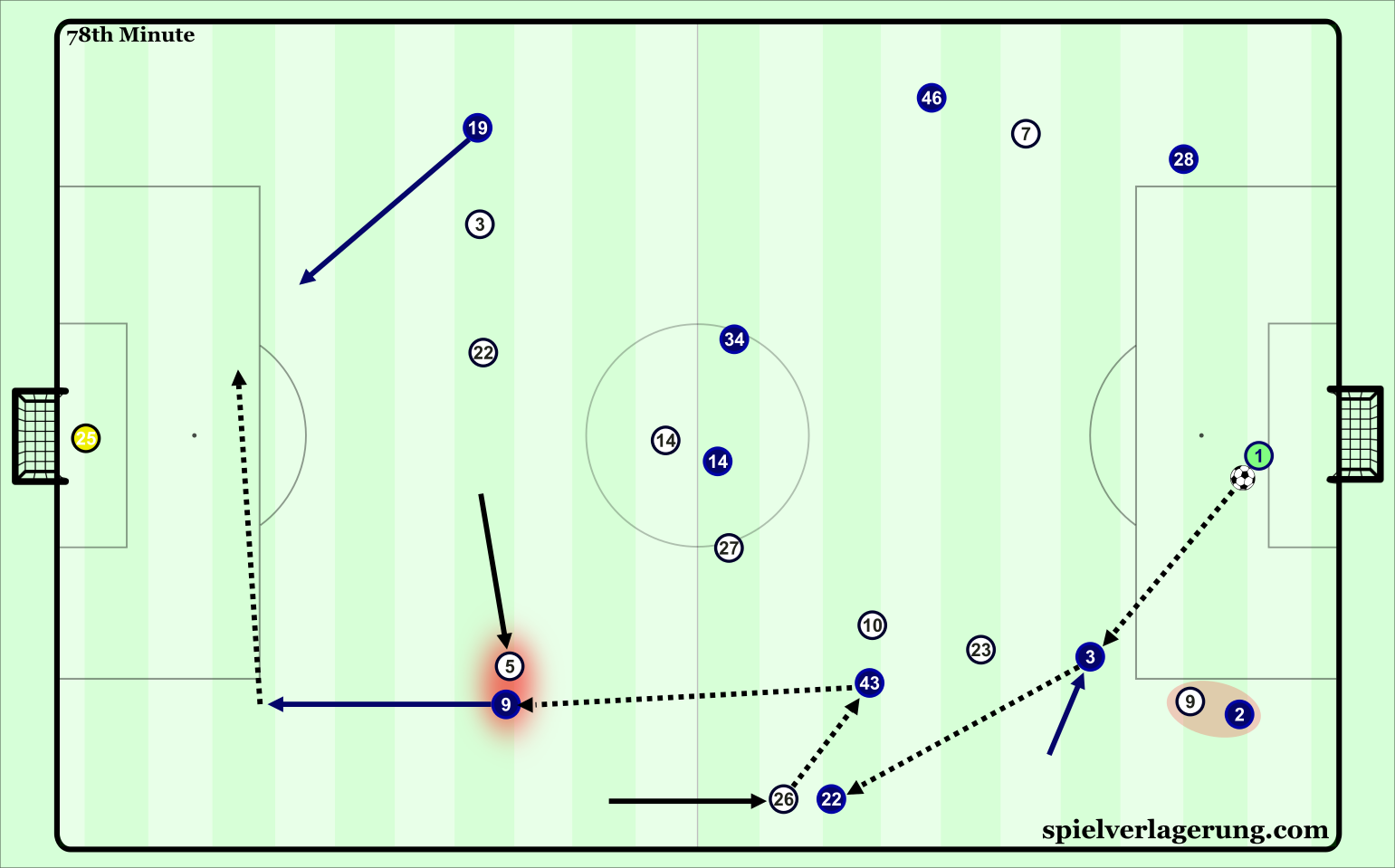

In a somewhat similar scenario, Douglas’ movement started the sequence that would end in Hernandez’ equaliser for Leeds.

Douglas (#3) intelligently moves into the left half-space with Ayling (#2) occupying McBurnie (#9) on the left-wing wide of the penalty area. Harrison (#22) has dropped to provide a short passing option to Douglas, pulling Naughton (#26) out of position in the process. Klich (#43) offers support to Harrison, who seeks Bamford (#9) in space ahead. Because Naughton is out of position, van der Hoorn (#5) is forced to pressurise Bamford, and gambles on intercepting Klich’s pass. He doesn’t. This leaves Bamford to dribble in behind Swansea’s retreating defence, who is then able to find Hernandez (#19) in the box who scores Leeds’ second equaliser of the evening.

Both teams had a chance to win the game late on, but ultimately the two teams couldn’t be separated with the match ending 2-2.

Conclusion

This match lived up to be an intriguing encounter. Graham Potter had a clearly defined game-plan to disrupt Leeds’ build-up and rhythm, which worked for the most part, leaving Swansea with a point and two wins and two draws from their first four matches of the season. Under the helm of Potter, Swansea should be considered amongst the promotion contenders this season.

This was undoubtedly Marcelo Bielsa’s toughest match as Leeds manager thus far. Despite remaining unbeaten, they dropped their first points of the season after approaching the match in a deficient manner. Neither team created many high-quality chances despite the four goals being scored; a draw was probably the fairest result.

This match slowed the Leeds-Bielsa hype-train a little by showing that they will have tough matches against difficult opponents to overcome this season, especially away from Elland Road. Fixture congestion may prove to be their downfall as a result of arguably limited squad depth, but players such as Bamford, Baker and Harrison are likely to be integrated into the team further in the coming weeks, with a few others to return from injury. This team is capable of winning the Championship under Bielsa, and will surely continue to be one of the more interesting and entertaining teams in English football this season.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen