World Cup Preview: Germany

The German team travels to Russia as current holders of the World-Cup title. And despite the DFB selection once again being named among the inner circle of favourites, perfection is nowhere to be found.

There’s no way Joachim Löw gets to bemoan too few personnel options. The long-serving Bundestrainer has the agony of choice, particularly in midfield. The fact that the German FA often elected to list midfielders only, foregoing a category for attackers, when announcing squads for friendly matches or qualifiers in recent years, may well have been a distinct clue as to how the people in power interpret the structure of their own team. There were no major differences in the assignment of tasks between those in the front line and those behind them.

However, that picture has changed in recent time. In Timo Werner, Sandro Wagner or forever-on-the-bubble Mario Gomez, Löw again and again called up players, who can almost only play in the centre of attack. Especially in the case of Wagner, who managed to return to Bayern Munich thanks to strong performances in the shirt of 1899 Hoffenheim, the footballing aspects were secondary. Wagner resembles the classic strong-man striker and aerial powerhouse more closely than most No. 9s wearing the DFB shirt in the past few decades.

Löw had to make compromises in the search for solutions in the middle of the playing field. Because attempts with players such as Mario Götze in the central striking role were either not entirely satisfactory or hard to sustain because of the injury-proneness of those chosen. Wagner’s games, on the other hand, had led to the German team playing a distinctively wing- and cross-heavy style. This worked well enough against mediocre centre-back pairings, against whom Wagner has the superiority in the air, but was never going to be an adequate way to play in match-ups with other power houses.

Maybe that’s why Löw somewhat surprisingly decided against taking him and instead opting for SC Freiburg’s Nils Petersen for his preliminary World-Cup squad of 27. Petersen, who did not make the final cut, also has good finishing qualities, but footballing-wise has a little more to offer than Wagner. That “certain something” is also missing from the 29-year-old’s game, however. Fans might have the same impression from Gomez if they only looked at his performances for the national team. That’s because he’s never truly sparkled for the DFB squad. His advantage over Petersen and Wagner, though, is his quality in the counter-attacking game. That’s what he was able to show especially in the last few months at VfB Stuttgart under Tayfun Korkut. There, Gomez often took part in the transitional game from a hanging position and redirected attacks after securing the ball.

In that context, though, Werner is clearly the better option. The RB Leipzig man is the better central forward for combinations and can shine in multiple situations. Especially with some vertical room he’s able to gather pace and, ideally, out-speed opposing defenders. Through the last season, in which Leipzig were forced to dictate play themselves more and more, and no longer able to constrict the game to counter-attacking situations, Werner also had to learn how to position himself during longer spells of possession. In these situations he can’t incessantly wait in the half-space on the edge of the central defence and take himself out of the rest of the game.

One group certainly never taking themselves out of the game is the German midfielders—of whom Löw has an entire legion at his disposal. Some of them are automatic starters because of their experience, leadership qualities and proven competitiveness. There’s no way past Thomas Müller, for example, even should the Bayern man not be an uncontested regular starter at the club level. Others have played themselves into the spotlight recently. That certainly applies to Leroy Sane.

The German export to England was among the best attacking players in the Premier League for months, even if his performances might have been overshadowed by Mohamed Salah in the public discussion. Sane offers qualities to the national team that, at best, Marco Reus can match. Sane’s straightforward playing style paired with his pace in sprints and dribbles make him an immensely valuable weapon particularly in the transitional game. Together with Werner he could have formed a counter-attacking duo that would run over a number of defensive lines after winning the ball. The fact that he otherwise often seeks to isolate himself on the pitch—as he does at Man City—will not find the approval of Löw and only fits into the playing concept of the DFB team to a limited extent. That was certainly the main reason that Löw, to the surprise of many, cut Sane from the final World Cup squad.

On the other hand, other potential wingers don’t have that special something in one-on-ones. Or they float between the wing and the No. 10 space. Julian Draxler is a good example for that. The 24-year-old brings a lot of talents to the table, but doesn’t consider himself a runner on the flank, rather a creator and passer. That’s why he’s similar to a few other midfielders on the team. Seeing as Mesut Özil is the unquestioned No. 10 in the German XI, though, it’s hard for his competition to get actual playing time. Löw has at times tried to play with two No. 10s, but recently preferred to play with real wingers.

The double pivot offers enough security on the ball and passing quality on its own to dominate the goings-on in the centre and direct the ball towards the important areas on the pitch. In Ilkay Gündogan and Sebastian Rudy there are creative and precise technicians for the spot next to Toni Kroos, though they may have to compete with the more robust and hard-running Sami Khedira and Leon Goretzka for playing time. Löw may well opt to go without a second play-making defensive midfielder if presence in midfield duels is more important to him against high-quality opposition.

There’s certainly no way around Kroos. The No. 6 of Real Madrid is the undisputed king of midfield in a team that is shaped by the bitter competition for spots in the starting XI. Nearly every attack is instigated by the 28-year-old. His movement and preferences inform the entire structure of the build-up. His passes and passing emphasis are decisive for the success of attacking moves.

Mats Hummels and Joshua Kimmich also belong to the core of the team—even though for entirely different reasons. Hummels has accomplished his status over the years, also by getting over smaller rough patches. Seeing as he’s injured much less often than Jerome Boateng, there’s no way past the experienced central defender. Ideally, Boateng will stand next to him on the playing fields of Russia and the familiar cooperation will have a positive effect on the entire German team.

Otherwise Löw would probably have to resort to Hummels and Boateng’s club colleague, Niklas Süle. He has the athletic and, individually, tactical basic components to establish himself on this level. But the more natural combination of Hummels and Boateng would be preferable also in view of the build-up phase. Other players shouldn’t play a huge role, at least not in a back four, even though Antonio Rüdiger has a particularly strong standing under Löw.

On the flanks it’s impossible to imagine a team without the aforementioned Kimmich. His past as a No. 6 in combination with his fundamental dynamism on the wing make him a tactically variable right-back. Löw has used Kimmich in a number of roles over the last few months. Once he was supposed to stimulate the play from the back and explore diagonal passing lanes into the midfield, another time he was a wing-runner on the flank away from the ball and responsible for crosses. Kimmich can do nearly everything. His counterpart, Jonas Hector, should be considered one level below him, but the Cologne man isn’t too far behind Kimmich. Hector has developed quite a bit, especially thanks to a lot of appearances in midfield, and has improved his strategic decision making.

The play on the ball

The German team will, if they make it that far, be the favourite in every game deep into the tournament, even being forced into that role. That means: long spells of possession and little vertical space will demand a lot of patience. Unfortunately, Löw’s men recently only demonstrated their ability to face that challenge at all times to a limited extent. Often the ball went through the lower lines very slowly. The contact times were high, the passing distance low. A lot of passes went wide and, when they attacked, their efforts often fizzled out.

Similarly to a lot of Bundesliga teams these days, the back four is definitely more suitable for the build-up play of the Germans. Automatically, there’s more space between the players, who should be able to let the ball travel over long distances without difficulties. At the same time, the spacing is more variable in the first build-up phase. As we know, Kroos very much likes to fall back into the left half-space. Without a half-back (the left centre-back in a back three) behind or beside him, he can vary the depth of his falling back better.

Incorporating the goalkeeper, meanwhile, only works insufficiently, despite Germany’s having two outstanding footballers at that position in Manuel Neuer and Marc-Andre ter Stegen. But seeing as no gaps in the half-spaces are left open, it’s borderline impossible for the goalkeeper to move up a few metres and create necessary passing angles, especially when the team plays a back five. Often enough he will basically stand on a line behind one of the defenders. When applying a back four at least he can move between the two centre-backs and, for example, help Hummels’ pushing forward. Those movements are a good tool to take the pressure off Kroos and destabilise the defensive balance of the opponent.

Also, a back four makes it easier for the German team to send a full-back into a run that ends in a cross with a steeper pass. Most of the time, the build-up stagnated severely when they attempted a back five. Wing-backs received the ball too deep and often had to turn forward. Subsequently, they played straightforward long-line passes towards the wingers, who with enough skill may have been able to produce a promising lay-off. Structurally, though, those approaches are middling at best.

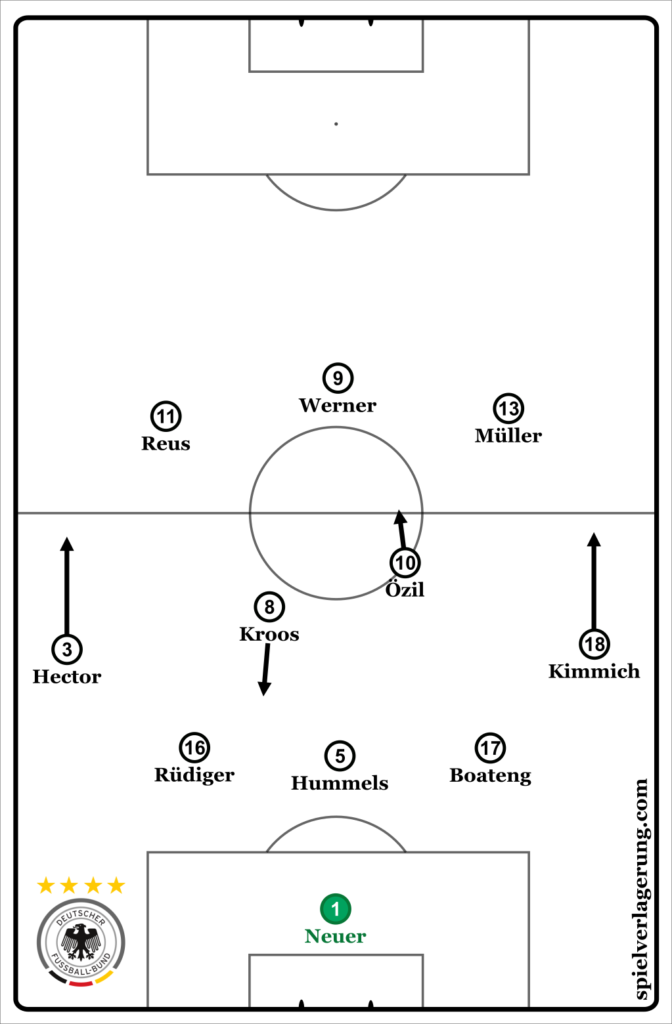

One thing the German team organises reasonably well in a formation including a back five is the positional fluidity in midfield and attack. In the more customary 4-2-3-1 the players move in expectable and often times gridlocked patterns. In a 5-2-3, though, the nominal wing-attackers are forced to drift into the half-spaces or the No. 10 space. The two holding midfielders have to fill into the vertical and, particularly, the diagonal to close gaps. The entire system is more dynamic, which works really well with the pace of a lot of German players.

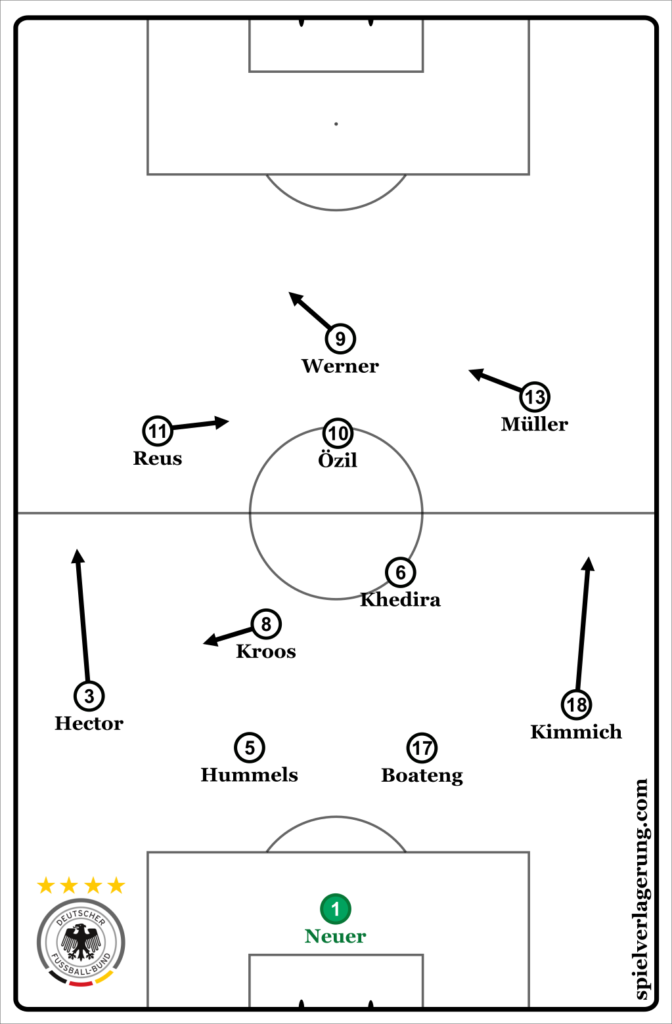

When playing with a back four, Löw recently tried to create some dynamism with hybrid positions. Especially on the right side he did this by using Leon Goretzka as a nominal right winger. The soon-to-be Bayern man tended to drift into the half- or No. 10 spaces, as he usually does, and left the flank for Kimmich. Seeing as Kroos structured the play from the deep left half-space anyway, it created a distinct diagonal axis which allowed the switching of sides.

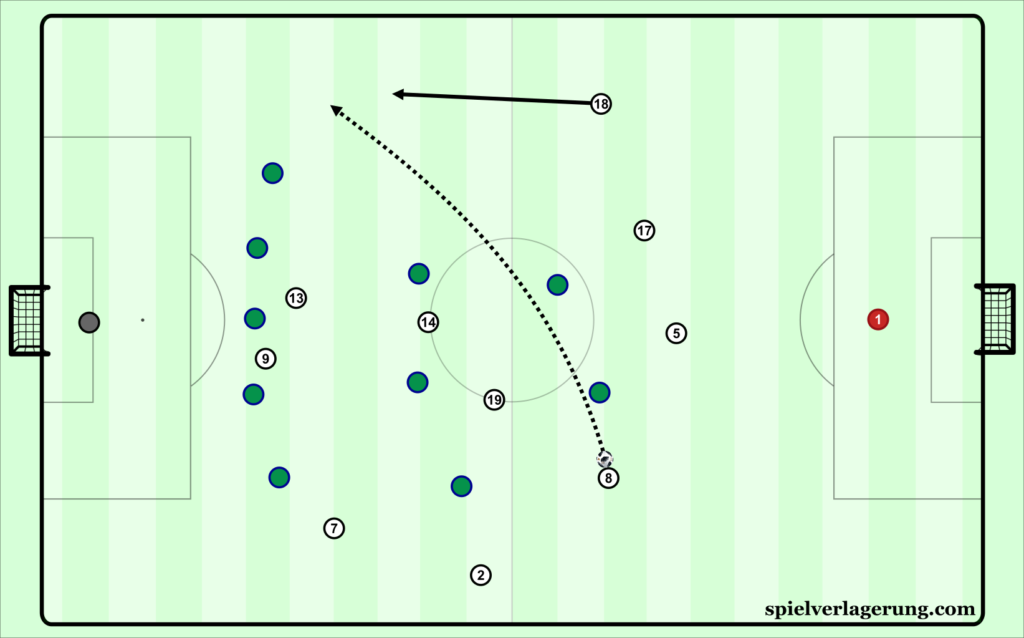

For example against Northern Ireland last year, there were a lot of long switches towards Kimmich, who then directed the ball into the box.

Something similar could be used at the World Cup. Because Löw has to create a certain imbalance in midfield. When both defensive midfielders are standing on the same line and too close to centre, they’re easily isolated. Gündogan might be the only player who’s able to dribble himself out of trouble, but even for him the danger of losing possession might be too high. Should the DFB-XI manage to lure the opponent to the left side of the pitch, Kroos’ precision with long diagonal passes will come to fruition. That way he could aim for Kimmich and gain a lot of space with one strike, at the same time exploiting the ball-orientated shifting of positions that is typical for most opponents.

Of course this is only a singular attacking move for the Löw team. In many ways the attacking play of the team is informed by anticipation and improvisation. There are a few passing lanes that they prefer to use. But, generally, the German playing style is similar to that of teams that are dominant in possession, who manipulate the opponent by way of long passing spells. Only here and there Germany will lose their patience and go for the sledgehammer.

The play in transition

Germany still score the most goals after winning the ball and transitional attacks. Especially with Werner and Reus—or alternatively Julian Brandt—close to the offside line, there are a lot of opportunities to overwhelm the opponent. Werner liked to start next to the centre-back and forces his dribbles, which in turn create space in the centre for players pushing forward. Reus does something similar, only a few metres closer to the touchline.

The fast counter-strikers can only shine, though, when Germany win the ball at least in the middle third of the pitch, and with their own midfield. Otherwise the direct transitional pass is hardly possible. However, the DFB team has only shown rudimentary approaches to pressing. A lot happens at low intensity and guiding movements are more exception than rule. Thus, a lot depends on the positional play of the No. 6 and No. 8 players. They can regularly intercept passes through strong anticipation and intelligent lurking. Löw has so far not developed an overarching concept, however.

Even still, one would think a “transition war” would favour the German team, seeing as the pace and individual qualities in pressing should speak in their favour. However, Germany often lose control in the chaos and surrender their compactness. Spaces in front of the defence are no longer adequately condensed. That precisely what cannot happen, though, because Kroos and company are a protective shield for the defensive line that isn’t consistent enough in the final stages of defending itself. Something that negatively influences Germany’s transitional game is their tendency to wait up front for too long after losing the ball, switching to the retreat too late. At times it’s the result of too slow a reaction time, at times the Germans will persevere in counter-pressing and attempting to win the ball back at all cost—to the disadvantage of their defensive stability.

The play off the ball

The aforementioned problems in the last phase of defending come to light especially against transitional attacks or, occasionally, the open build-up play of the opponent. Germany’s defensive vulnerability of the past has other reasons as well—such as wobbles under pressing pressure. Brazil underlined that fact in one of the last friendly matches ahead of the World Cup. The record champion attacked very early and marked Germany in man-orientations. The centre-backs were at times marked as early as on the short sides of the penalty box.

Here and there, there wasn’t even time for a long whack of the ball. Seeing as Löw’s team also tried to find footballing solutions to situations by playing low passes, but tended to make mistakes under pressing pressure, they lost the ball in their own half quite a bit. No defence in the world looks good following this. The vulnerability, then, stems from a less-than-optimal build-up structure against pressing, which gets us back to the start.

Germany can and probably will concede the odd goal from classic attacks. From time to time they lack access on the wings, the correct movements in duels or the right positioning for crosses into the box. But weak spots in the build-up phase undermine the entire playing philosophy of the German team. Without assuredness on the ball they lose any kind of dominance. And, following what we know about transitional battles, you need that dominance to create and sustain stability.

How to beat Germany?

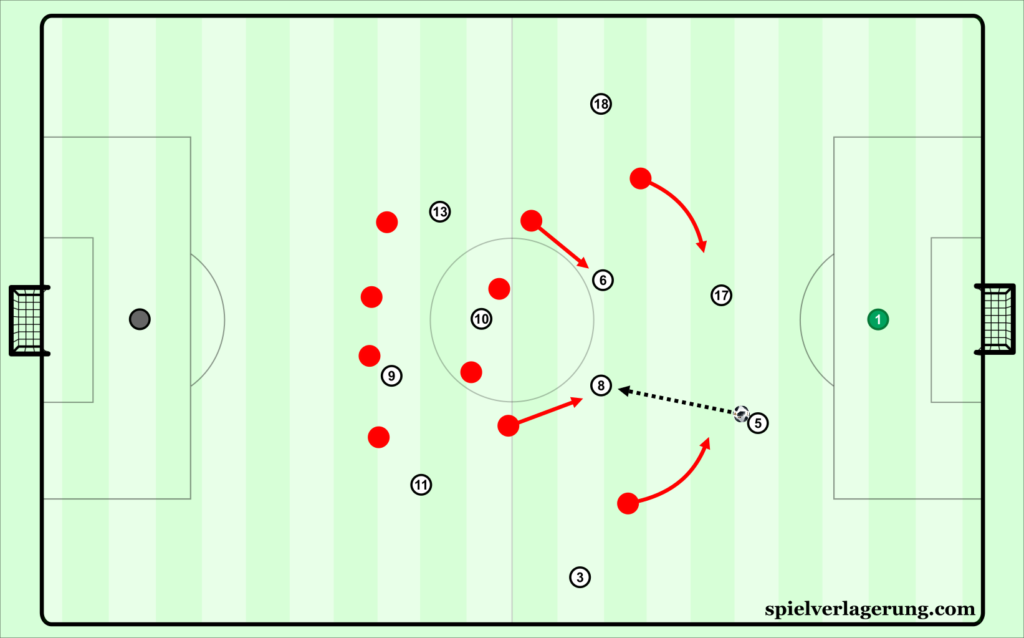

Even though the holders are among the favourites, it seems likely that Germany will stumble at some point of the tournament. Especially the last few months have shown how to beat Löw’s XI. It starts with the aforementioned man-orientated pressing, that needs to be executed with the necessary level of intensity and continuity. And it ends with a deliberate forcing and winning of one-on-ones on the flanks.

Additionally, there are a few smaller tactical wrinkles that should work against Germany. For example, an opponent could leave the centre quite open in the first pressing phase and run at players from the outside. That way the German full-backs would be stuck in the cover shadow during forward-pushing movements from the wingers and passes would be guided inside. The two German defensive midfielders could be packed close together in the centre because of the wider positioning. Applying pressure would be easy as a result. Backward passes toward Hummels and Boateng would have to be answered by collectively moving up the pitch.

Against Germany it’s paramount for every team that it’s not too comfortable in the build-up phase. And it seems easier to press the DFB XI early on than to fill gaps with a deep midfield-press and win the ball. The distance to the goal would be high and the German centre-backs are clever and experienced especially in two-on-two situations. In many instances they’d be able to run with the opposing strikers. The bigger danger for Germany’s defence is when Hummels and company have to wait at or inside their penalty box. They might not have the necessary explosion and reaction rate over the first two or three metres.

An alternative?

Germany won the Confederations Cup last summer. Of course you can argue the value of that competition and Löw only used what can be generously described as a 1-B XI. But the tactical wrinkles in that tournament were very interesting. In some ways the Bundestrainer copied the approach of Thomas Tuchel, by overloading the right side of the field with a number of players of high footballing quality, letting the team work the diagonal and thus creating isolations on the wing opposite of the ball.

This could also work at the World Cup. Because Kimmich, Kroos and Gündogan have the technical potential to combine themselves into those overloads and, at the same time, to solve the bottleneck situations at the correct moment. Reus and Brandt, meanwhile, are two wingers who love being isolated and prefer to act in those free spaces. This way of playing would be a clear alternative to the build-up play going through Kroos and the left half-space and would create more flexibility and unpredictability. Especially seeing as shifting play toward Reus are very promising in terms of subsequent breakthroughs. However, Löw has made no efforts to recreate this alternative from the Confederations Cup.

Forecasting the tournament

Germany will face an interesting cast of opponents during the group stage. But no other team should pose too much of a threat for Löw and his men. The obligatory stumble in the second match of the group stage would have to be forced by Sweden, which seems fairly unrealistic considering the footballing limitations of the Scandinavians.

Should Germany win Group F they would probably face a manageable opponent such as Switzerland in the round of 16, unless Brazil slip up. The first bigger test would wait in the quarter-finals, when they could face Belgium or England. This schedule, obviously basing on theoretical assumptions, would work in the Germans’ favour. Because, usually, Löw manages during an ongoing tournament to refine the processes in his team’s play and focus on a few approaches that work.

Something that speaks against the German team would be the questionable fitness levels of a number of players and the improvable athletic activity in the team. From the round of 16 or the quarter-finals it could rain down muscular injuries unless the signs some bodies will send will receive the proper attention and reaction. Key figures such as Boateng could push themselves to the absolute limit, like at Euro 2016 in France, and crumble akin to a house of cards.

They cannot make up for a deterioration of athletic quality. At the 2014 World Cup Löw focused on keeping his team stable tactically and making things work through man-orientated work and smaller adjustments in midfield. Without the necessary fitness levels they would not have won the title. Ahead of this World Cup the omens have changed insofar as Germany are going into the competition with less stability. It’s difficult to see at this stage how they would compensate for decreasing strengths with superior tactics and a strategic direction. If Löw were to manage this, though, he would prove a lot of doubters wrong, just like he did in 2014.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen