World Cup Preview: Argentina

Argentina struggled to qualify for this summer’s World Cup in Russia. They have been drawn into what could be a very competitive and difficult group, but they have the potential to challenge for the trophy if everything comes together for them.

Introduction and Squad Description

The national team have tended to be overly reliant on Messi in previous major international tournaments, but this group consists of many capable, technical, and versatile players that can be utilised to a greater extent under Jorge Sampaoli in comparison to previous Argentina coaches.

Argentina have played with a different system in almost every game during Sampaoli’s year-long tenure as the coach. The versatility of the squad means that Argentina are competent at adapting between the variety of formations and systems that Sampaoli has at his disposal. Whichever system he decides to use, Messi is allowed the freedom of movement to be the focal point of Argentina’s attack, whilst the rest of the team maintain balanced spacing and structure around him.

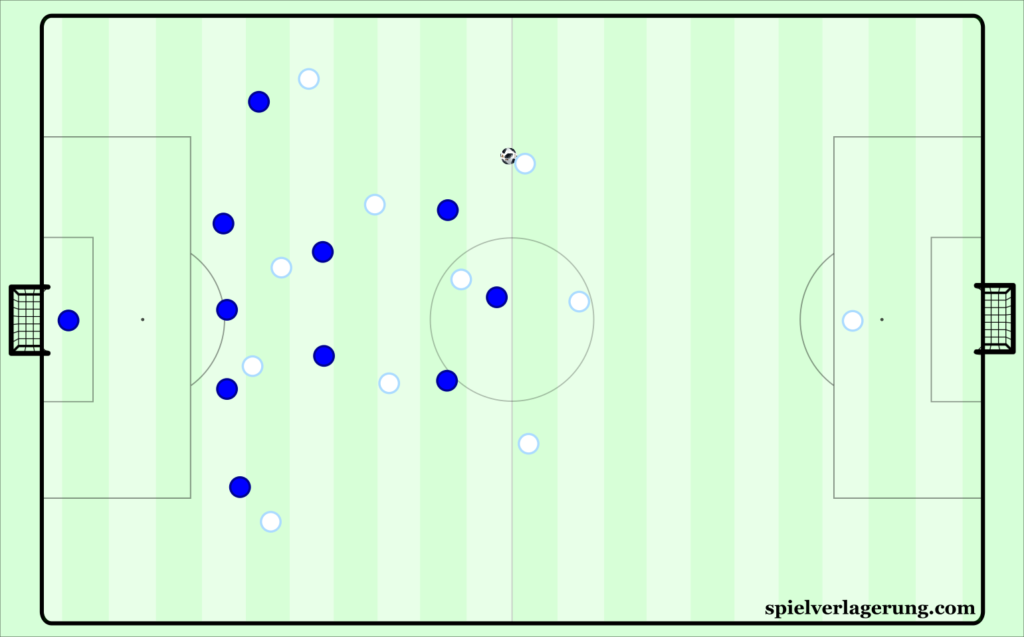

Formations

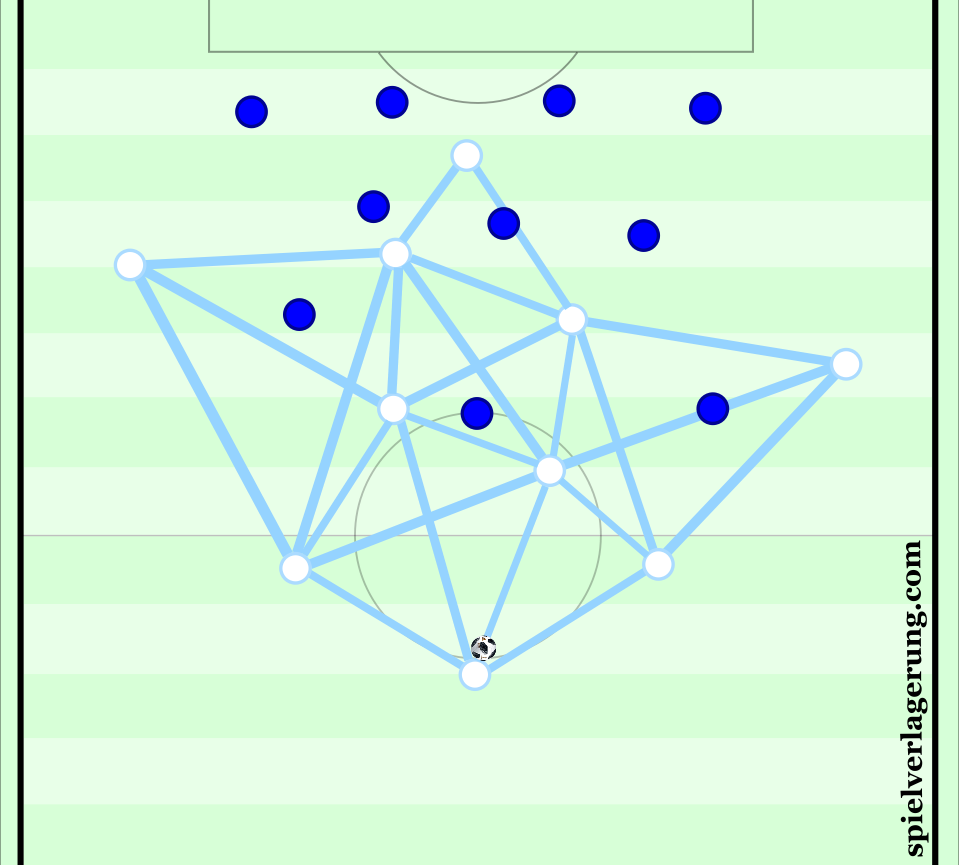

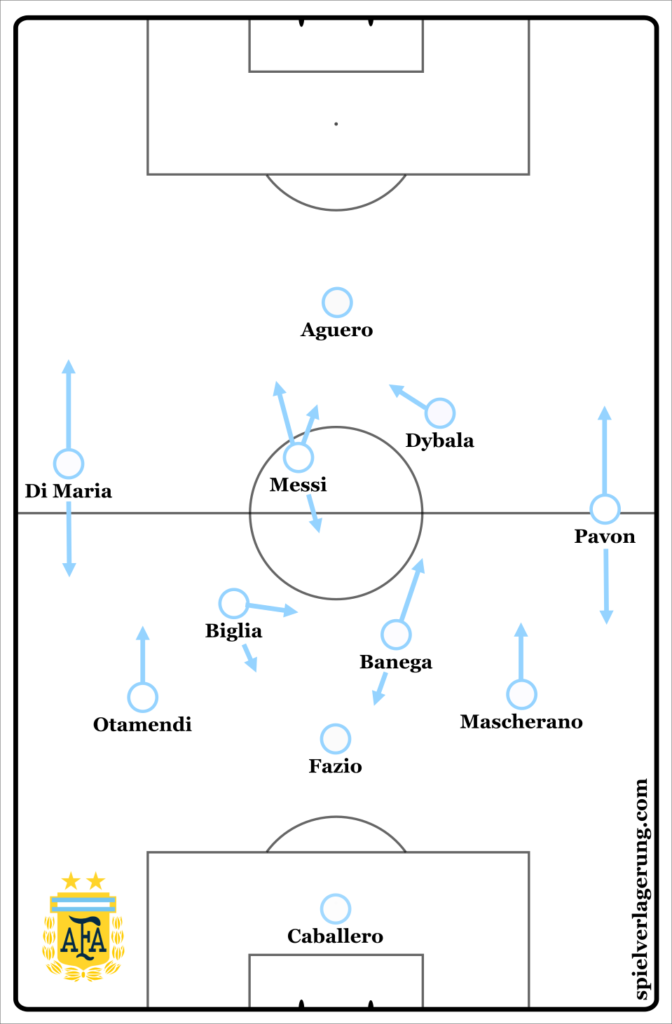

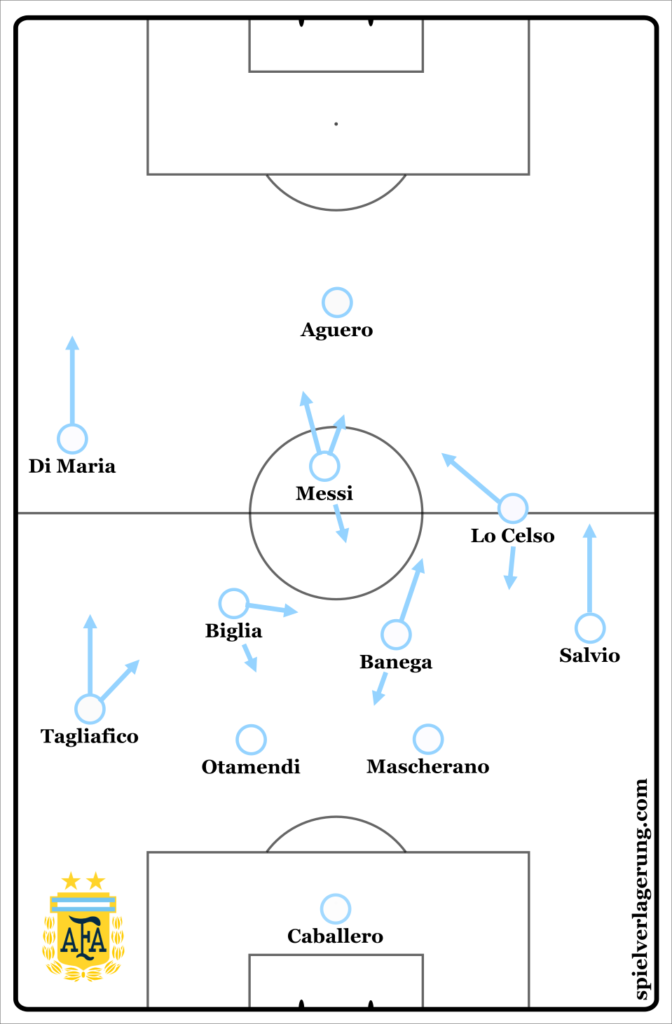

Pictured above are three of Argentina’s main formations under Sampaoli. They are subject to adjustment and adaptation by the coach to each opponent Argentina face. Their different systems and structures will be analysed in more depth throughout the preview.

Attacking

Central Penetration and The Role of Messi

To state the obvious, Lionel Messi is Argentina’s key player and attacking focal point. He is crucial in maintaining and creating triangular connections between teammates (especially in midfield), connecting the midfield to the forwards, and progressing attacking sequences through the centre of the pitch.

Messi often drops deep into midfield from the #10 position to help Argentina’s construction and progression through the phases of the pitch. He finds intelligent spaces between opponent players and defensive and midfield lines, allowing him to receive the ball, turn into space, and either dribble at the defence or pass the ball to more advanced players, usually the wingers. This was repeatedly seen in Argentina’s matches against Brazil and Russia.

The forwards can have a prominent role in progression through the centre of the pitch too. Against Italy, Higuain made smart movements away from the centre-backs to lay-off to onrushing midfielders, whilst Aguero also executed similar actions in the match against Russia.

However, as you might expect, Argentina struggle to penetrate defensive blocks in central areas when Messi isn’t playing. In their match against Brazil last June, Argentina played 3-4-2-1 with Messi and Dybala as #10’s. The two proved incredibly difficult to cover, with Dybala often playing his best football for the national team when playing alongside Messi. He’s effective when playing as a lone #10 in a similar role to Messi, but unsurprisingly is not as skilled in finding intelligent spaces and connecting teammates to each other.

This shouldn’t be too much of a concern as Messi is likely to play every game for Argentina at this summer’s World Cup, but even when he is playing they sometimes struggle to play through the centre of the pitch. As great as Messi is, Argentina occasionally need to direct their attacks towards other areas of the pitch…

Wingers and Wing-Backs

One of the most interesting aspects of Sampaoli’s Argentina is the way wingers are used. When playing a system with three central defenders, Sampaoli often plays wingers in wing-back roles, the most interesting being the frequent use of Angel Di Maria as a left wing-back. His physical attributes make him suited to this position, and despite typically operating as a more advanced out-and-out winger, he is usually one of Argentina’s most important players. Wingers are also sometimes used by Sampaoli when playing with four defenders, most commonly being the use of Eduardo Salvio at right-back.

In matches where it is difficult for Argentina to penetrate defences centrally, such as against Italy’s deep 4-5-1 block, they are often forced to the wings in order to develop their attacking sequences. One of their main methods of breaking down opposition defences is to create situations where wingers can either isolate against opposing full-backs, or alternatively to run outside of the full-back to get in behind the defensive line.

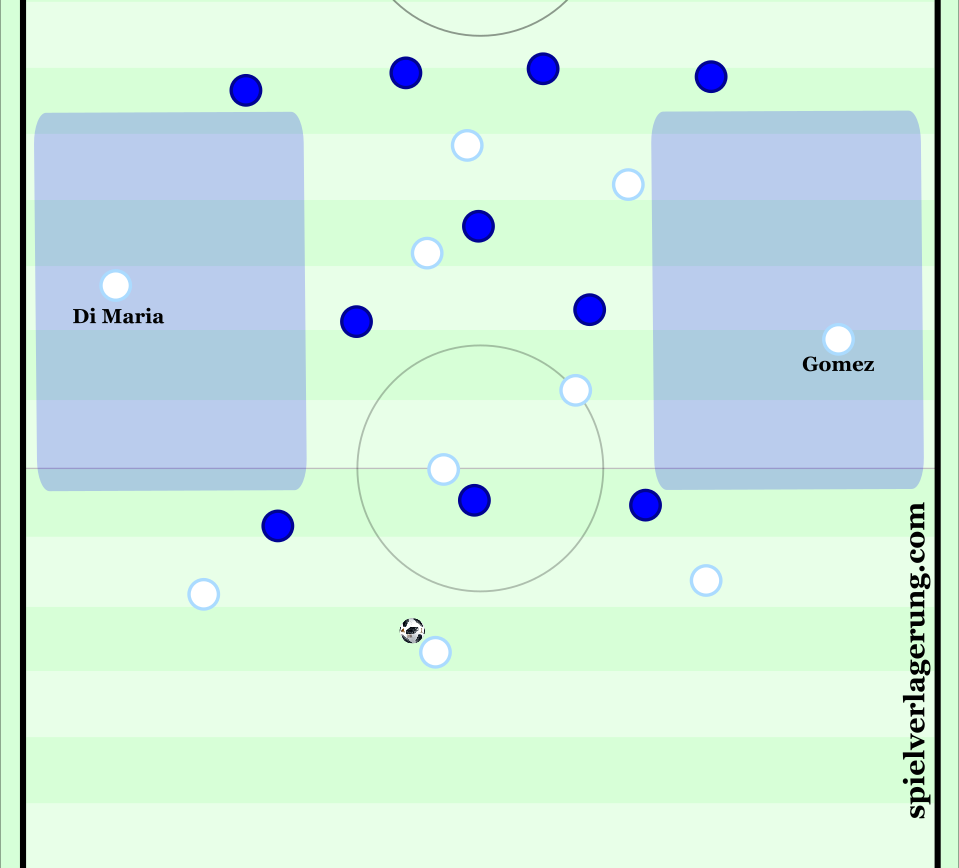

This was also the case against Brazil’s compact 4-3-3. The wing-backs Di Maria and Gomez had vast spaces to themselves for the majority of the match, and were key passing outlets for playing out of defensive phases, as well as for attacking midfielders in central areas. Messi, for example, would frequently pass the ball to Di Maria from a central position, creating numerous opportunities for him to isolate against Brazil’s right-back.

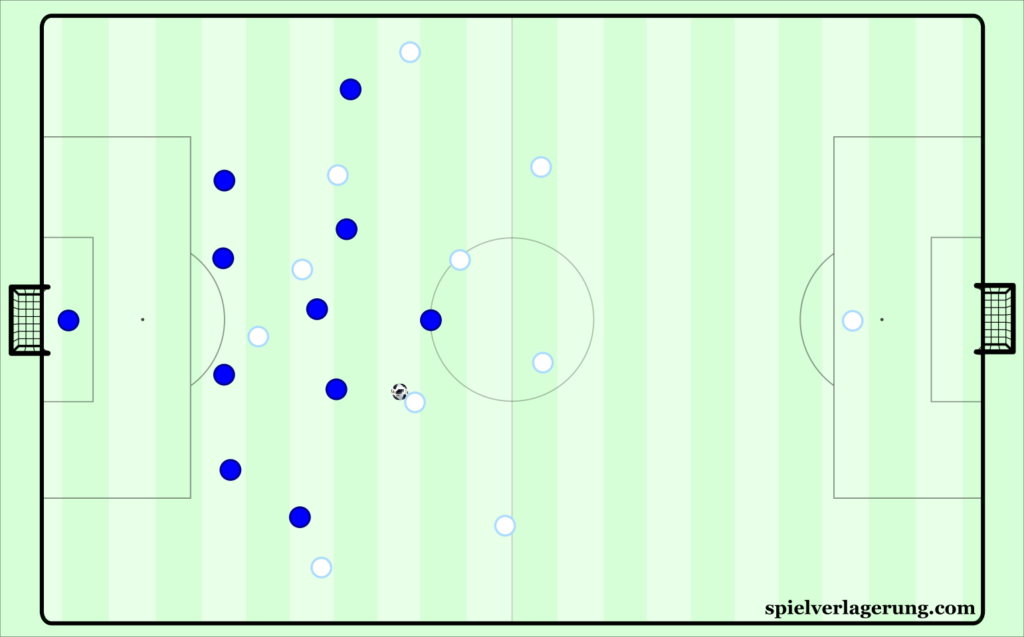

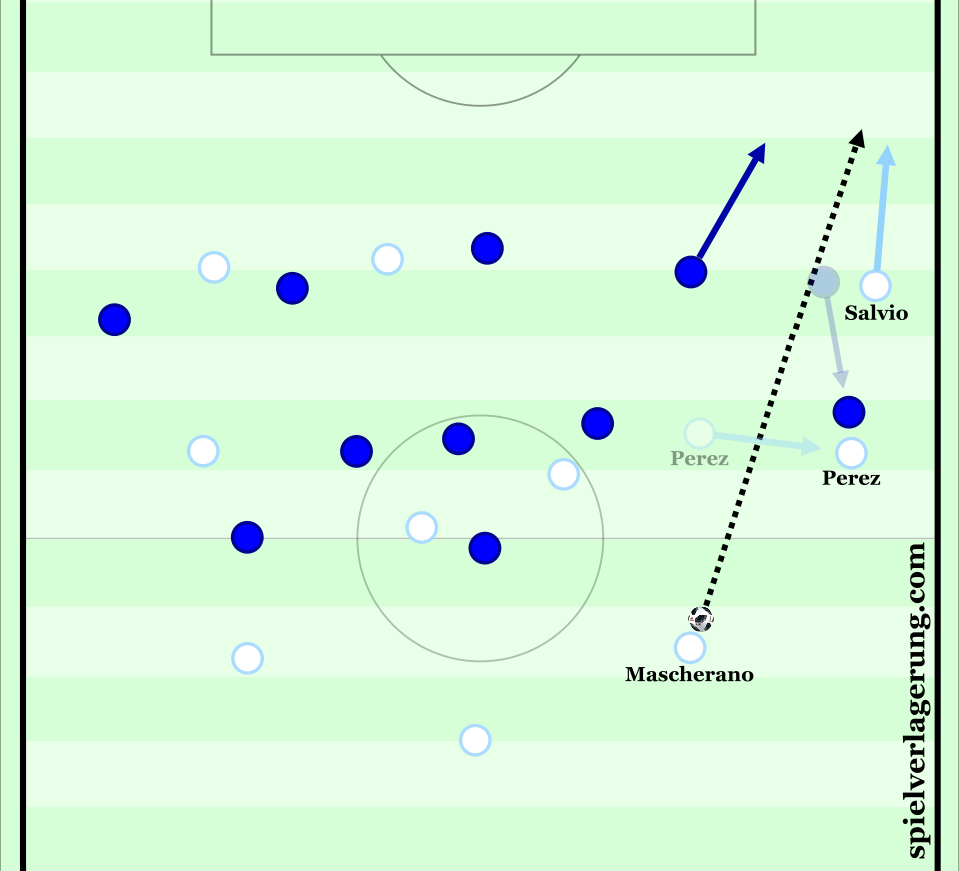

When playing 3-5-1-1 against Russia, Argentina’s outside central midfielders moved into wide areas to make connections between the outside centre-backs and the wingers. This created more space for the #10 (Messi) to operate in, whilst also drawing opposing defenders out of the defensive line towards them. This created space for the wingers to run outside of and in behind the defence, as in the example below:

The positioning of the outside central-midfielders in this match allowed the wingers/wing-backs to advance further up the pitch and occupy the opposing wing-backs. From this position, they could also choose to move inside into the half spaces, leaving the outside central-midfielders to occupy the wing channels. Likewise, when playing 4-2-3-1 against Italy, Argentina’s wingers (Lanzini and Di Maria) occupied the wing channels, and the full-backs (Bustos and Tagliafico) made underlapping runs into the half-spaces. During these situations, the wingers and full-backs could make quick, effective, and progressive connections with each other through the wide areas of the pitch.

When Argentina’s wingers successfully run outside of their defender and receive the ball in behind the defence, they commonly play a pull-back/inside pass. This is due to the increased efficiency of both retaining possession and creating goal-scoring opportunities by playing pull -backs/inside passes as opposed to crosses. Both of Aguero’s goals against Russia and Nigeria were assisted by such inside passes.

Arguably, in many of the matches over the last year where Argentina have struggled to score, a significant reason as to why they struggled was because of the slow tempo in many of their attacking moves. They almost exclusively broke through opposing defences when successfully passing to their wingers when running beyond opposing full-backs via long passes. Thus, the use and effectiveness of Argentina’s wingers/wing-backs in Russia are likely to be a decisive factor in determining how well the team performs this summer.

Build-Up

Argentina are comfortable playing out of defence from the goalkeeper against very high pressure. When the goalkeeper has the ball, the centre-backs position themselves wide, outside of the penalty area, whilst the midfield and wing-backs/wingers position themselves close to the defence, helping them to progress with possession away from their goal and the defensive phases of the pitch.

Whilst Sampaoli’s player structure is the greatest determinant towards playing out of defensive phases of the pitch successfully, individual player quality is also very important. Nicolas Otamendi is a player to keep an eye on during these moments. His development as a player when in possession of the ball means that he can make more intelligent decisions with it. For example, he regularly seeks to play vertical line-breaking passes.

There are however circumstances where Argentina struggle to play out from the goalkeeper, such as against Nigeria’s man-orientated pressing in a match they lost 4-2. When Caballero had the ball, Nigeria’s front three players were man-orientated to Argentina’s three centre-backs, whilst also pressing from an angle that prevented an Argentina player in their cover shadow from being a passing option. Furthermore, Nigeria’s wing-backs advanced out of their defensive line to press Argentina’s outside central-midfielders.

Caballero tended to pass to the full-backs hugging the touchline, Bustos and Tagliafico, when Argentina’s centre-backs and central-midfielders were unavailable. Another reason Argentina struggled in this match was because of Nigeria’s physical superiority. This was especially the case in midfield, where Giovani Lo Celso often found himself in a duel for the ball against John-Obi Mikel or Wilfried Ndidi. It will be very interesting to see if (and how) Sampaoli and Argentina change their approach from last November’s match against Nigeria for their re-match in the group stages of this summer’s tournament.

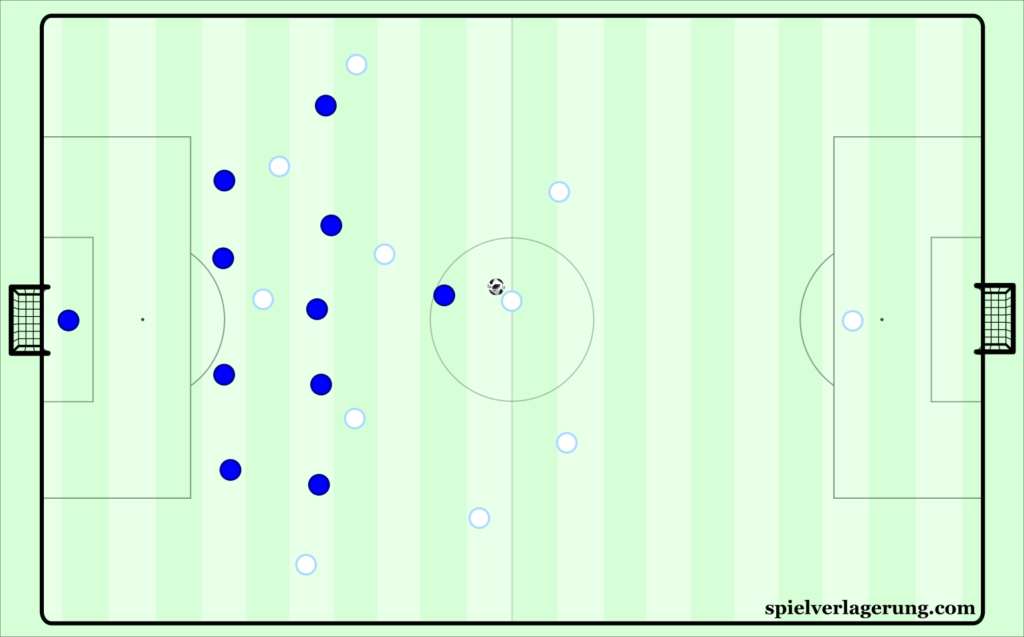

In terms of build-up play which is closer to the halfway line than the goalkeeper, Argentina maintain depth in their structure and positioning. When playing three central-defenders, the middle centre-back always positions himself deeper than the outside centre-backs (this is inverted when the goalkeeper has the ball – the outside centre-backs position themselves deeper, with the middle centre-back moving into a comparatively more advanced position). The four central-midfielders (the two #6’s and two #10’s) in Argentina’s 3-4-2-1 stagger themselves to create triangulation. This can be seen from their match against Brazil below:

Ever Banega is Argentina’s most important midfielder in deep build-up play, playing a wide range of intelligent passes, expertly recycling possession, and by moving intelligently off the ball in relation to his teammates. Against Brazil, Banega, playing as the right #6 (alongside Biglia as the left #6), had a particularly important role in Argentina’s build-up play in the second half of the match (this followed Sampaoli changing Argentina’s system from 3-4-2-1 to 4-2-3-1 at half time). By moving from a central position in the first half to the right half-space in the second half, Banega forced Brazil’s outside left central-midfielder, Renato Augusto, to follow him. This made Brazil’s midfield uncompact, thereby creating more space for Messi and Dybala to operate in. Banega’s intelligent off-ball movement make him vital in Argentina’s build-up play and manipulation of opposing defences. Other Argentina players occasionally play a similar role in the right half space to Banega’s role against Brazil, such as Giovani Lo Celso in Argentina’s 4-2-3-1 against Spain, and 4-4-2 against Haiti.

Argentina’s midfield frequently inter-change roles with each other in central areas of the pitch. This positional fluidity helps to disorganise and manipulate defences, creating spaces to operate in. When Messi decides to drop from the #10 position to aid build-up play and the progression of attacks, the fluid structure of the team means that Messi’s teammates can adapt to his movement, maintaining connections and suitable spacing between teammates to retain possession. The combination of Messi’s sporadic dropping movements and the team’s fluid positional structure make Argentina’s build-up play less predictable and one-dimensional, and therefore harder for opponents to defend.

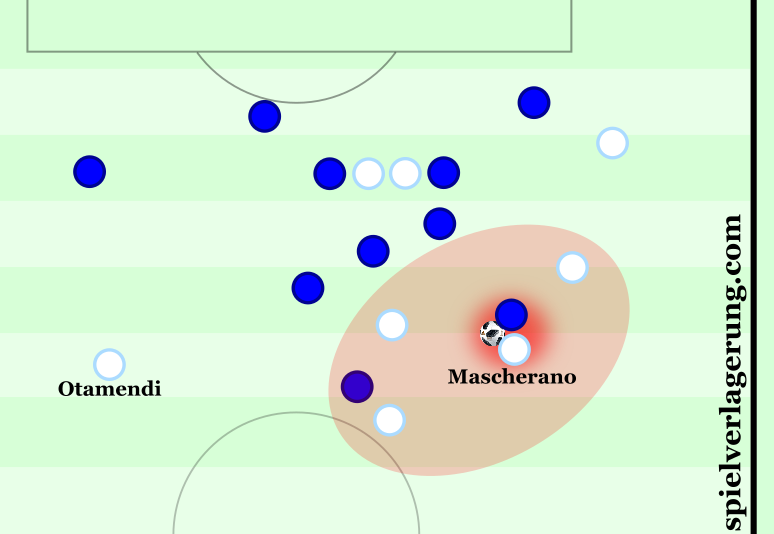

Additionally, Otamendi and Mascherano commonly advance out of the defensive line and dribble through the half-spaces into the opponent half when the space presents itself to do so. By doing this, they give the central midfielders permission to advance further up the pitch, meaning Argentina have numerical superiority in an abundance of attacking situations.

Transitions

Argentina are very aggressive in attacking transition, usually allowing a minimum of five players (including the player on the ball) to run at the defence. This normally includes the two forwards (the striker and the #10), two wingers, and one central-midfielder. Alternatively, when playing with two #10’s, the central-midfielders will stay back, whilst the forward, two #10’s and two wingers break ahead.

A moderate proportion of Argentina’s best goal-scoring chances are generated via attacking transitions. Their three most common methods of attacking in transition are when the wingers receive the ball in large spaces in wide areas, counter-attacks after winning possession, and when successfully playing out of defence from the goalkeeper, through midfield phases of the pitch and into the opponent half. This is common when the opposition press aggressively and have a high defensive line.

Defending

Argentina’s defence struggled in World Cup qualifying, but have shown improvement under Sampaoli. Argentina have kept a clean sheet or only conceded one goal in almost all of Sampaoli’s games as coach, with their two matches against Nigeria and Spain being the exceptions (it should be noted that Argentina didn’t play a full-strength team in either of these matches).

Under Sampaoli, Argentina have shown the ability to change between a three and four-man defence, both between and during matches (e.g. moving from 3-4-2-1 to 4-2-3-1 against Brazil at half-time). Sampaoli’s preference for versatile players, capable of playing a variety of positions, means that the group of eleven players in Argentina’s line-up have the capacity to play different systems without any substitutes having to be made.

Pressing

Argentina usually press opponents in a man-orientated fashion. They press opponent defences when playing a system that positions players in more appropriate locations to do so. For example, playing 3-4-2-1 instead of 3-5-1-1 against Brazil meant that Argentina had an additional attacking player to press Brazil’s defenders. Yet, by playing 3-4-2-1 instead of 3-5-1-1, Argentina had two central-midfielders rather than three, meaning they had less defensive cover in the centre of the pitch. When playing 3-5-1-1 against Nigeria, Argentina did not press their defenders, to then step up the aggression of their pressing in midfield areas.

When Argentina have attempted to press opponent defences when using impractical formations, their attempts to force the opposition into turnovers are often unsuccessful. This was the case against Italy, who were regularly able to play through Argentina’s press. Nevertheless, due to Sampaoli’s propensity to adjust the team’s system if there are glaring issues, such situations tend not to last whole matches.

Argentina defended in a 4-4-1-1 shape (deriving from their 4-2-3-1 base) against Italy. Lo Celso, Argentina’s #10, man-marked Italy’s #6 (either Verratti or Jorginho). This could be a strategy that Sampaoli uses at the World Cup in an attempt to neutralise opponent #6’s, perhaps in the group stages against Croatia’s excellent central-midfield.

When defending inside their own half against Nigeria, Argentina’s 3-5-1-1 moved into a 5-3-2, maintaining their very high defensive line, with less than ten yards between the defensive and midfield lines.

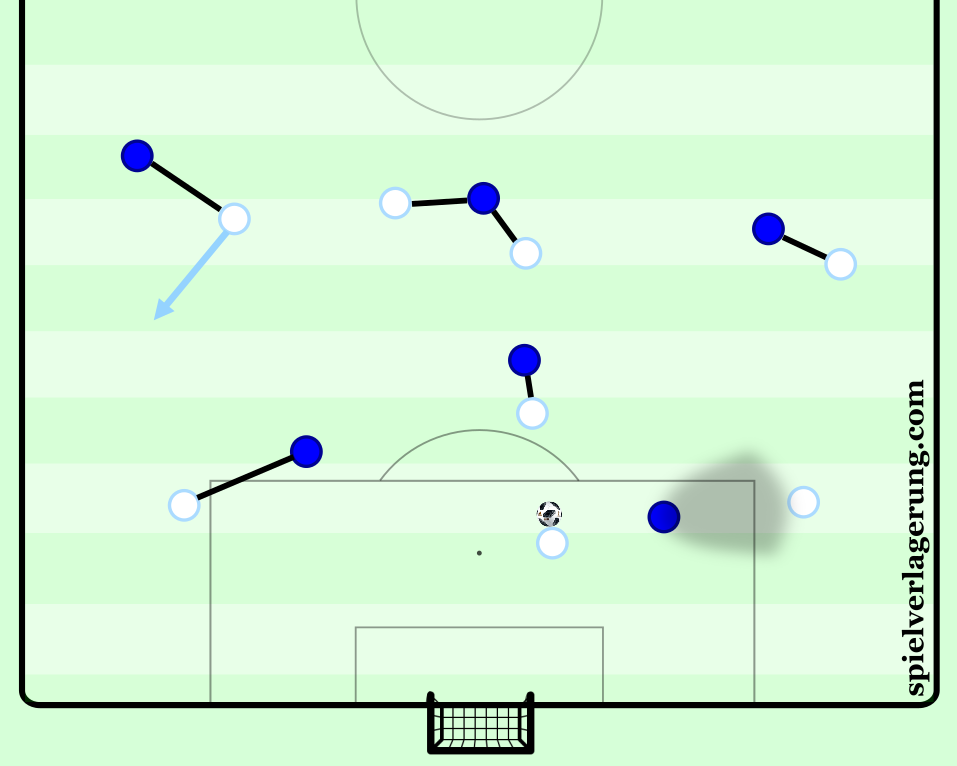

When pressing inside the opponent’s half, Argentina’s midfield stay close to the forwards, creating vertical compactness, limiting the space for opponent players to operate in. Additionally, the defence sometimes move inside of the opponent’s half to compact the space between themselves and the midfield. This occurred in Argentina’s match against Russia. Otamendi and Mascherano advanced well into Russia’s half when Argentina were in possession. The pair also counter-pressed very aggressively following Argentina turnovers.

Argentina’s midfielders were also aggressive in their counter-pressing during these moments, often pressing Russia’s forwards from behind, creating scenarios were the player on the ball had no available passing options, as in the example above. A substantial percentage of Argentina’s best chances in this match were generated in attacking transition after winning the ball inside Russia’s half.

Transitions

As you might expect, when playing with three central-defenders, Argentina’s main weakness is the exploitable space left in wide areas of the pitch. From a defensive perspective, playing wingers as wing-backs is not an optimal strategy. Every so often, the wingers’ advanced positioning when Argentina are in possession leave the defence vulnerable. This proved to be the case against Nigeria, whose second and third goals were produced via attacking transitions through the spaces left on the wings by Argentina.

The defence can also be left vulnerable if Argentina’s outside centre-backs as part of a three-man defence advance into the opponent’s half. They are sometimes reliant on Mascherano and Otamendi’s individual defensive quality when defending in one-on-one situations to stop counter-attacks. The experienced Mascherano uses his anticipation and aggression to prevail in the majority of defensive match-ups he faces. But Argentina can’t be reliant on individual defensive quality alone to prevent teams from scoring against them at the World Cup.

Expected Starting Line-Up

Out of all the teams at the World Cup in Russia, Argentina’s starting line-up is one of the most difficult to predict. Due to Sampaoli’s inclination to adjust and adapt the team to each opponent, it is likely that Argentina’s line-up will change on a game-by-game basis. They have looked more stable with four defenders on the pitch rather than playing wingers as wing-backs alongside three central-defenders. Therefore, depending on the level of opponent Argentina face, I think their starting line-up will be very similar to one of the two variations below:

Firstly, Caballero is likely to start in goal following Sergio Romero’s injury and subsequent withdrawal from the squad last month. Mascherano and Otamendi are almost certain to start in defence whatever system Argentina play, as are Banega and Biglia in midfield. Tagliafico will probably start at left-back when Argentina play four defenders, with Salvio at right-back. Sampaoli has favoured Salvio over Pavon in the right wing-back/winger role, preferring Pavon as an out-and-out right winger. On the left-hand side, Di Maria will be the wing-back/winger in whichever formation Sampaoli uses. Dybala is likely to start alongside Messi when Argentina use two #10’s, but I think Lo Celso will be chosen over Dybala when Argentina require greater stabilisation in midfield. Manuel Lanzini would have been likely to start in this position before his injury and withdrawal from the squad last week, after performing well for the national team over the last year as an interior playmaker from a wide right position. Finally, I expect Aguero to be favoured over Higuain due to his superior creative and pressing ability.

Conclusion

The performance and results of a Jorge Sampaoli-coached team can often be a bit of a mixed bag, but the pieces of a collectively outstanding Argentina team are there to be put together. If Sampaoli is the man to deploy a system(s) that utilises Messi without under-utilising the rest of the team, giving him the freedom of movement to be the attacking focal point whilst surrounding him with balanced spacing and structure, then Argentina could be a serious threat to go all the way in Russia. Could this finally be the year that Messi gets his hands on the most coveted trophy in football?

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen