SV Observatory – Volume II: Istanbul Derbies

For the second edition of the SV Observatory, we profile the two biggest matches in Turkey over the weekend. League leaders Galatasarary visited their eternal rivals Fenerbahce over on the Asian side of Istanbul, sitting in fourth pace prior to kickoff. Elsewhere in the city, newcomers to Turkish success Istanbul Basaksehir hosted Besiktas, where both sides hoped to close the gap to one point on Galatasaray.

The Intercontinental Derby

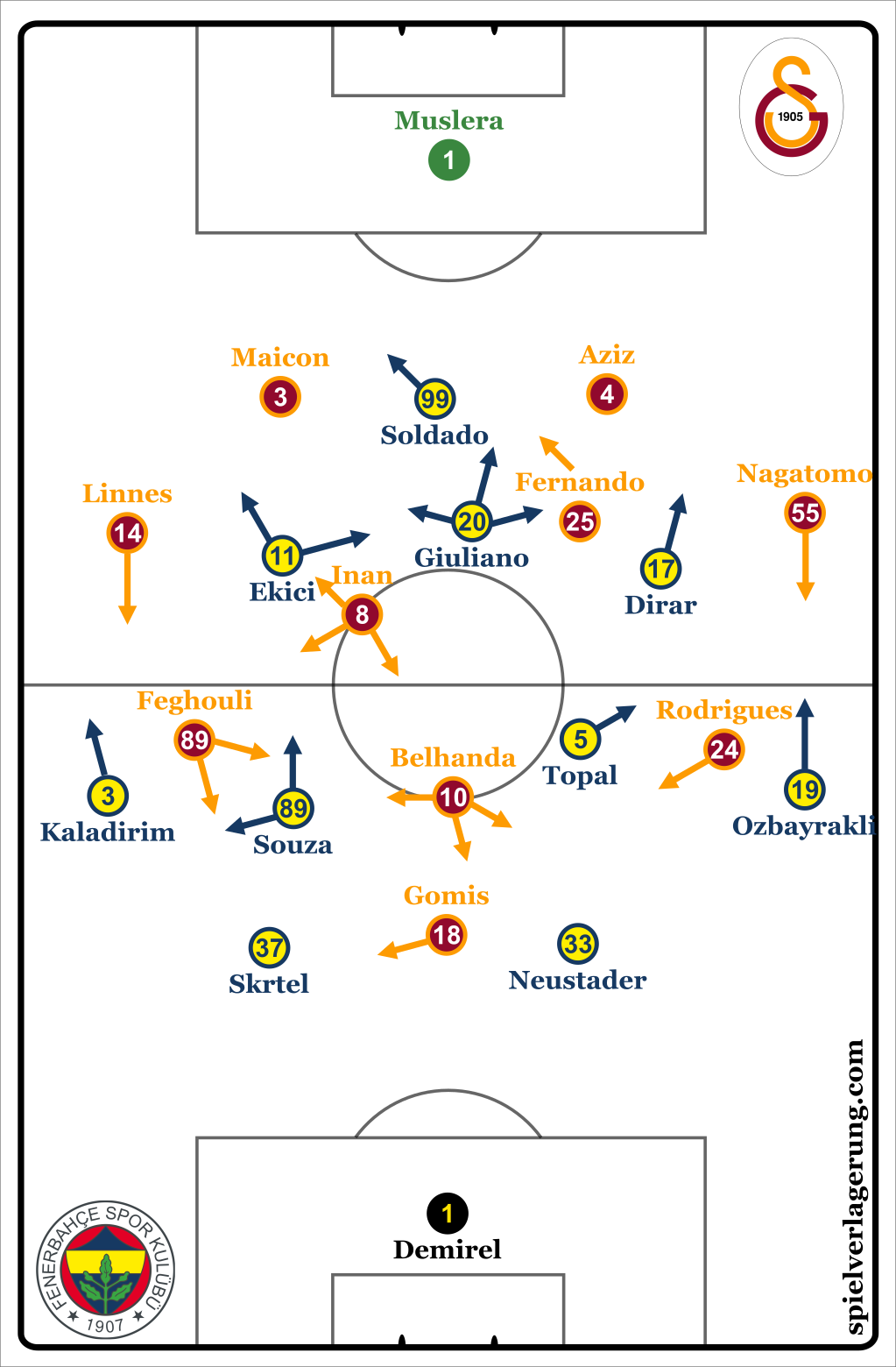

A back and forth 0-0 draw. After starting with a series of chippy moments featured with significant amount of fouls and more direct play, this match provided intrigue through narrow attacks and contrasting approaches to pressing. Each side had somewhat similar base formations, showing a 4-2-3-1 throughout most of the match with similar principles regarding attacking and responsibility of each player. For example, both clubs had a more defensive holding midfielder, an another that was delegated with more of the distribution as a deep-lying playmaker.

Fenerbahce demonstrated more fluidity between their front four than their rivals did, with that positional freedom playing into their methods of pressing the opponent. Galatasaray exhibited a bit more caution earlier in their attacking and defensive play with some moments of promise. This however allowed Fenerbahce to exert more of their influence on the match in the first half, and subsequently come closer to scoring.

Galatasaray

Galatasaray’s conservatism was headlined with their 4-4-2 midfield block, which had Belhanda move higher to join Gomis. Their line of confrontation was approximately 40 meters from the goal. Behind the duo, the defensive line moved the team up rather high, about 10 or so meters from the centre circle, with the midfield ahead of them about a similar distance. This compacted the centre of pitch quite tightly from a vertical perspective, while horizontally, the outside players remained close to the interior, ensure Fenerbahce could not easily play into their attacking midfielders.

Wingers moved up to pressure when passes were played to the opposition fullbacks or when any passes were played wider than the width of the penalty area to the centre backs (in cases were they pulled wider), but this wasn’t a defining feature of Galatasaray’s defensive strategy. For longer spells of opposition attacks, they committed many defensive numbers to defend in deeper areas. While this kept Fenerbahce off the score sheet, it conversely led to them being trapped in their own half for long durations, allowing their rivals to have long continuous intervals of attacks.

In attack for the league leaders, Fernando would drop into the defensive line to form a three-chain at the back, pushing the fullbacks up the pitch slightly so they occupied closer distances to the wingers. Inan would roam in between the line of fullbacks and the attacking midfielders, sometimes occupying spaces too close to the wings for effective circulation ahead of Fenerbahce’s pressure from their front four. The only true central presence came from Gomis, either as a target man for long balls, or when he checked in front of Neustader to link up with other players.

Belhanda was only in the centre in coincidences where he found himself there, as he had no true positional requirements and moved wherever he felt would be a good chance for him to get the ball. Since he loved the right halfspace, this made Feghouli’s narrow positioning excessive. The Algerian was narrow as a way to invite Linnes to run forward and attack with the ball, but this seriously limited the dynamic of the away side, as these positions failed to move around their opponents and open up avenues to penetrate. Their most common forms of penetration came in the form of long dribbling runs from Rodrigues, the penalty area being flooded with Galatasaray players when Linnes would get the ball for crosses, and some quality combination play in short distances ending with Gomis peeling off and taking a shot prematurely.

Fenerbahce

Fenerbahce had their wingers move inside and fullbacks higher in order to play around Gala compact centre, with the same mission of getting chances through crossing as their opponents. Their attack had similar components of individualism, except with the main pillars being predominantly central as opposed to wide. The attacking midfielder trio showed high fluidity and played close to each, aiming to play Giuliano in behind from a deeper starting position to out run Galatasaray’s defense and break towards goal. Through these quick three-player combinations, interesting combinations were pulled off, and Galatasaray only could deal with these moments by clearing the ball or kicking it out of bounds. Some build up was present, with the main conductor being Souza. However, he at times moved excessively (and even comically) far back to get a foothold of the ball, rendering some of his positive intentions nonfunctional.

One of the more interesting developments of the match was Galatasaray’s inability to adequately deal with the counterpressing of Fenerbahce. Typically initiated by the front four, they were quite good in terms of how they applied immediate pressure to the ball when they were in appropriate distances to do so. The surrounding players intelligently used their cover shadows to block passing lanes, with those players being the next players to recover possess in the instance off any deflections or tackles applied to the player with the ball. Galatasaray frequently had no answer to this, only looking to solve by dribbling and thus conceding possession quickly.

Similarly, the same front players would aggressively chase Galatasaray’s defense following any clearances from their backline, with such pressing taking on homologous properties as their counterpressure. Due to the fervor of Fenerbahce’s attackers when it came to pressing, there were two issues that arose during the match. First, when they would recover possession, they were often overbalanced toward the ball. This led to instances in possession where they could not switch the ball out of the area where they just won it, as the centre midfielders (alongside other players) were too close to the ball on the wings. Or, they were ignored in favor of forcing forward passes into tight areas that had little chance of succeeding. Additionally, because of the manner that the front men pressured, large gaps between them and the midfield/defense formed, leaving Galatasaray space in between the lines to play with if they had suitable occupation there. In the second half, they targeted this region through a different way than other top teams utilize.

Long Balls – The Solution to Two Different Problems

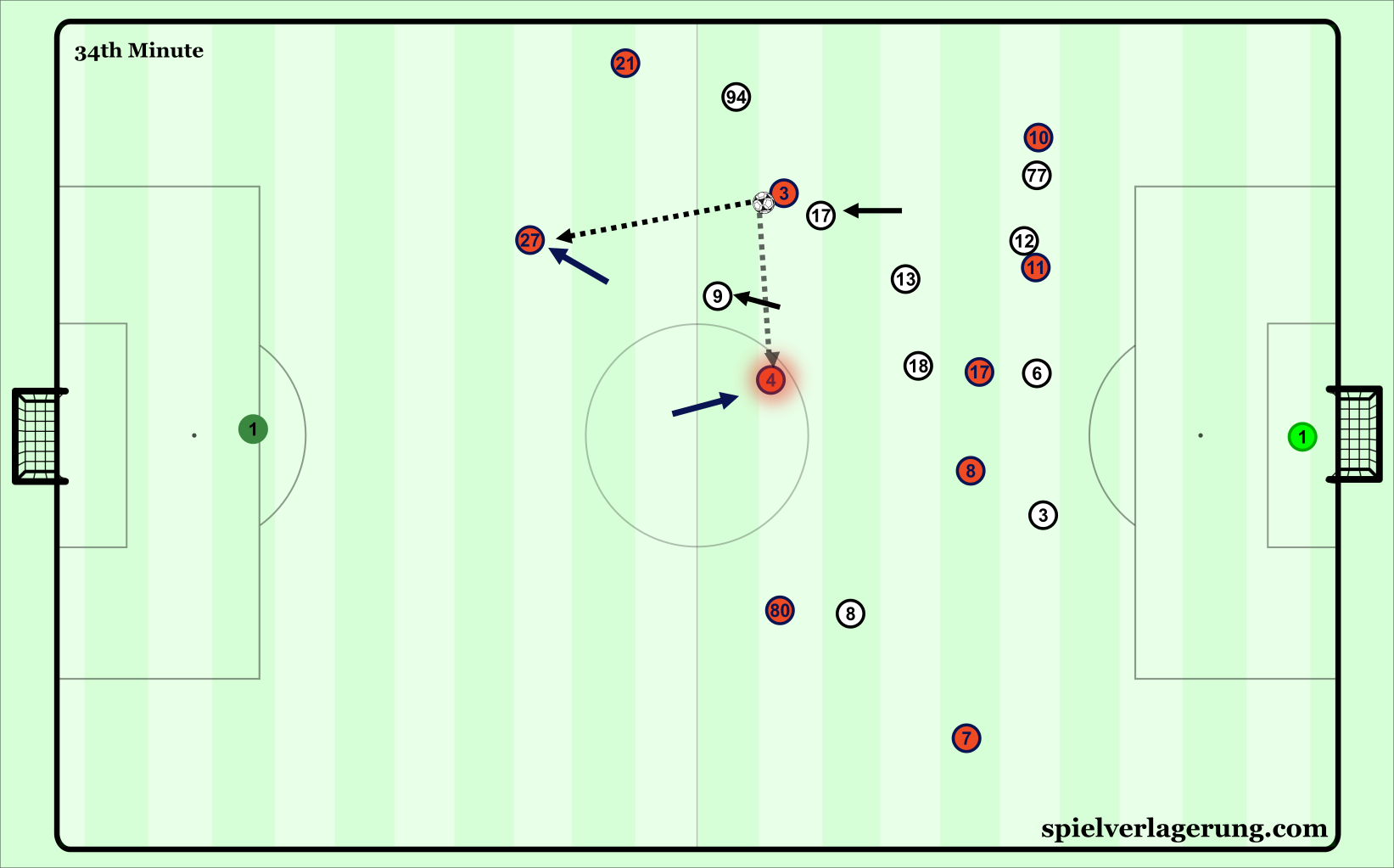

Soldado and Giuliano were relentless with their pressing. Coupled with Galatasaray not having an adequate structure to easily solve these situations, Fatih Terim decided to have his club play more long balls into Gomis to progress his team forward. With the space in front of the centre backs ever increasing, Galatasaray had decent success at moving up through winning second balls and using the following seconds to dribble at Fenerbahce to break.

Belhanda became more of a force in the attack for the away side, while the narrow starting spot of Feghouli increased the chances of winning the second balls and moving forward. If in the possession of wingers, they aimed to dribble toward the byline to find the central options through a cutback, not really establishing the entirety of their team in the opponent’s half to have prolonged spells of possession. Similar to the first half, chances were created through mainly individual moments. Rodrigues had a lot of success in the newfound openness of the game, almost breaking the deadlock either through his own efforts or by being a catalyst for his teammates.

In the first half, most of Fenerbahce’s chances were somewhat dervied from their pressing and their fullbacks, struggling to get in behind. The second half increased the frequency and the targets of long balls in behind Galatasaray’s high line, as Soldado and Giuliano were the main objectives in the first half. Since they couldn’t pass into Giulano’s feet from the build up, they evaded the midfield pressure of Galatasaray all together and began to be multi dimensional in their long balls by playing wide sometimes rather than just high. These passes would put Galatasaray on the back foot and force them to track towards their own goal, gaining territory for Fenerbahce while avoiding the compact block of players in centre midfield.

Fenerbahce changed to 4-2-2-2 with the introduction of striker Fernandao, further strengthening the home side’s central foothold and better equipping them for the newfound aerial profile of the match. The substitute mainly just made the game more direct on both ends, as Fenerbahce’s attacks were much shorter lived and numerous, leading to the same pattern from Galatasaray. Even though he had a goal (rightly) disallowed, the Brazilian was the human embodiment of the chaos that the last portion of match brought. Adding Mathieu Valbuena late on to improve the attacking third quality was an additional stroke that Aykut Kocaman painted onto the match, but this didn’t add much composition to Fenerbahce’s attacks as a whole and didn’t provide the difference needed for three points.

The last portions of the game were fitting for the reputation of the derby. The mania from the fans equally manifested onto the players desires to score and foul the opponent, that they almost forgot about the game itself. A fair result for both teams.

The New Derby

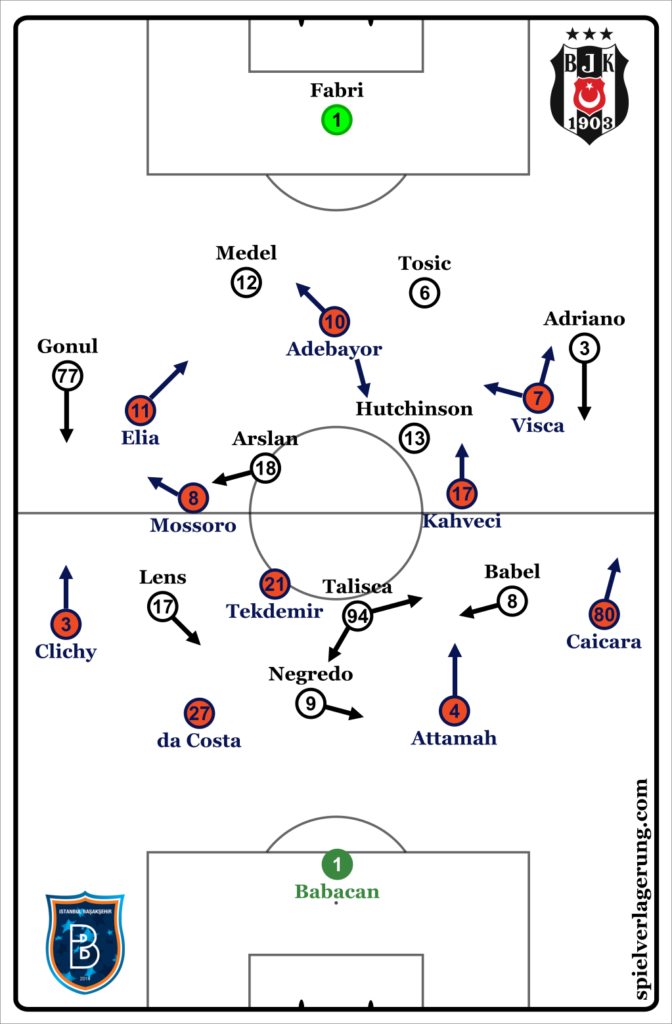

Started from scratch a short time ago, Istanbul Basaksehir is now in the process of turning the “Big Three” of Turkey into a “Big Four”. This will upset the traditional power brokers of Istanbul, but with a more stable and shrewd approach of bringing in players and being more open to advancements in the sport, they have now established themselves as one of the country’s best teams. There’s other components related to the politics of the club’s funding that may interest some viewers, but that doesn’t interest me as much as Sunday’s match.

Basaksehir Attack

Unlike their compatriots from the match earlier this weekend, Istanbul Basaksehir had a somewhat high risk possession system, as shown with Babacan forming a chain with the two central defenders quite close to his goal at times. Centre midfielders took up large distances away from the defenders during build-up, indicating a high level of trust between them to navigate Besiktas’ pressing from their attackers.

Since Basaksehir had the bulk of possession in the opening phases of the match, the front players for Besitkas became restless and accordingly moved up their pressure without much coordination from their teammates behind them. Since Da Costa and Attamah were quite comfortable on the ball, they easily broke the disjointed pressing from Negredo and Talisca through dribbling the first player and playing to the next player that was vacated in order for the second player applying cover to get to the ball.

The current champions were somewhat quite man-oriented in defense, leaving their man when more urgent options moved into their area. This left Besiktas open defensively, making their pressure easy to navigate. They ended up being quite uncompact as a result of being stretched out by Basaksehir’s expansive shape in possession.

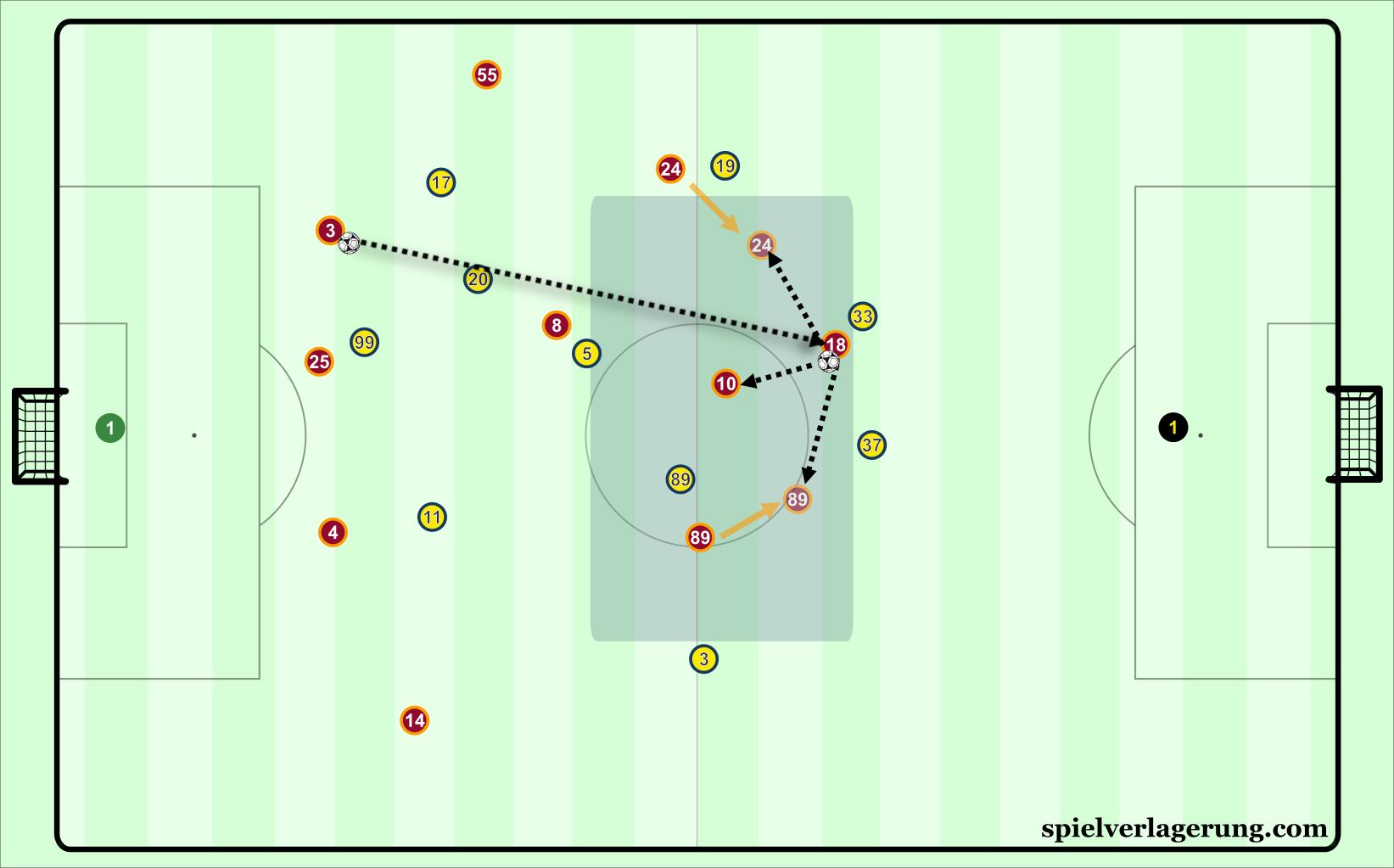

The home side were also interesting when it came to how they circulated possession in the attacking half. Adebayor had almost total freedom to move into spaces that he saw available. This provided an additional option to play around Besitkas’ man-orientations, as their centre backs did not follow him into the spaces that the Togolese roamed in. To maintain structural stability, either Visca or one of the centre midfielders would drift towards the middle and occupy his spot, ensuring that there was representation in all the vertical zones of the pitch. The fullbacks were not very adventurous in their positioning, acting instead as more support for any dead-ends on the wings to play back into the centre. With Adebayor floating around and a centre midfielder higher, Joseph Attaman would step up from defense and function as his teams’ pivot. Da Costa would drop even deeper to provide a last resort option out to restart their attacks, allowing his team to get back into their positions if the previous attack didn’t result in anything promising.

Attaman steps up into the midfield here to act as a pivot, with Da Costa dropping deep to provide another option. Clichy elects to play Da Costa, despite Attaman being available once Negredo steps up to anticipate the ball back.

For chance creation, Istanbul had a couple of ways that they seriously threatened their opposition, capitalizing on their superiorites for their given side. On the right side, they predominately aimed to cross and find Adebayor as a target man. Adebayor would float toward Besiktas’ right centre back, Gary Medel. Medel is one of the shortest high level defenders in the world, so the height mismatch led to many positive sequences for the hosts. Visca and Caicera had great understanding of each other and with Babel not tracking back very far to contribute to defending, the 2v1 formed on the wings led to many Istanbul attacks originating from the right. On the other side, Eljero Elia was the most threatening player on the dribble throughout the match, cutting side to link with teammates or shoot for himself. His attempts were mainly blocked, but the Dutchman scored the lone goal to guide his team to three points.

Besiktas Struggles with Basaksehir Pressing

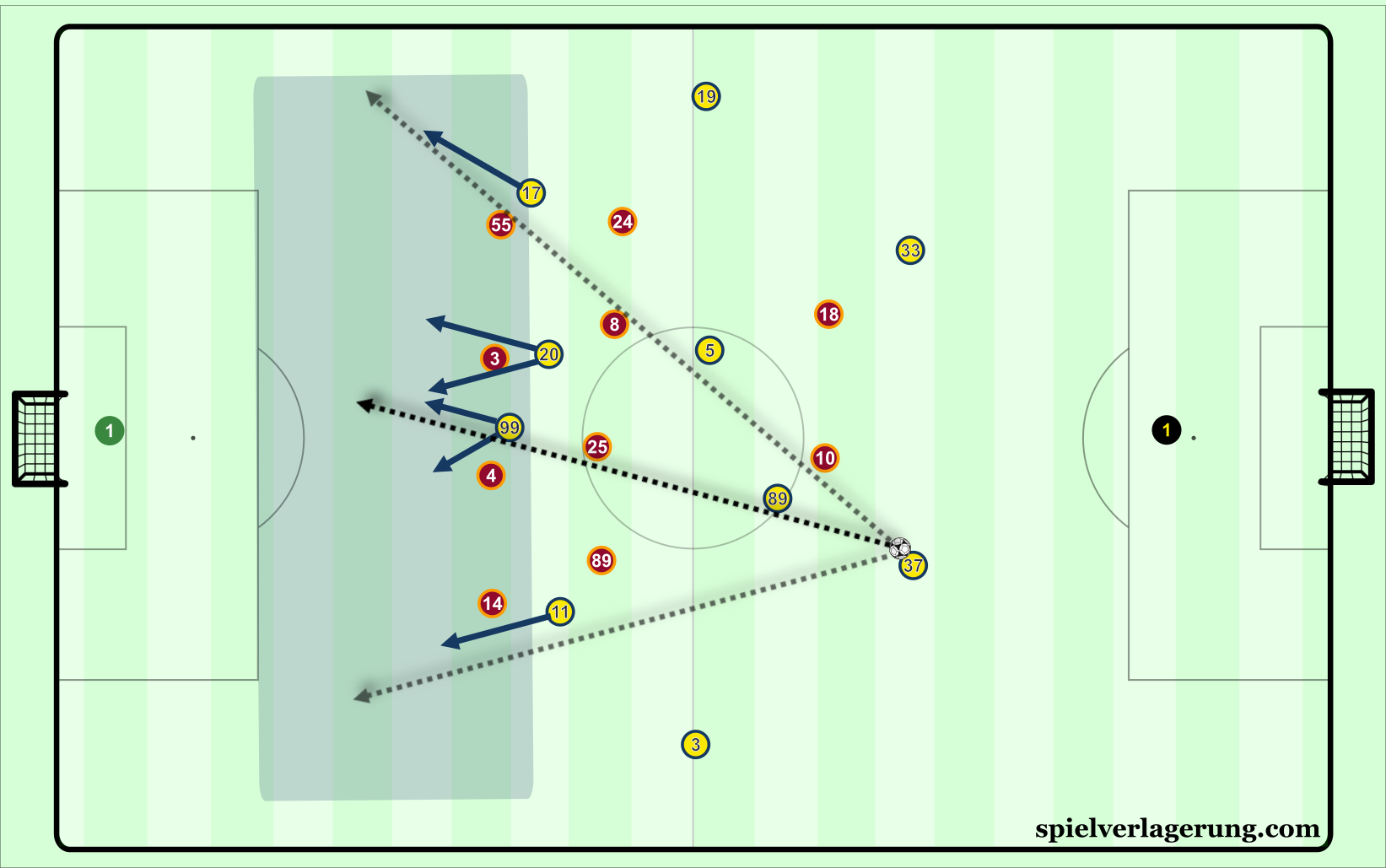

Thanks to the pressure that Basaksehir applied without the ball, Besiktas barely posed a threat despite having multiple advantages in talent. The hosts were quite controlling in the manner that they pressed, limiting options behind them by starting in positions where they could intercept passes easily if targeted near them, while also readily anticipating passes to players in front of them so pressure could be applied immediately. Basaksehir were wise when it came to the spots they chose, as when Babel or Lens would try and create space for themselves with double movements, the fullbacks anticipated these developments well and negated them. With Besiktas having a majority of their attacks come from wider areas, Istanbul’s pressing became easier since they could lock their opponents into one segment of the pitch.

However, Basaksehir’s pressing success was not entirely their own doing, as Besiktas had multiple issues of their own in possession. Starting from the front, Anderson Talisca was frequently too far ahead into the next line, anticipating passes in behind to run onto. Rather than remain in between the holding midfielders and Negredo, the Brazilian instead was prioritizing the likelihood of scoring instead of influencing the match as a playmaker. This led to few quality options in front of the ball to pass to, rendering much of Besiktas’ sideways and backwards circulation useless when it came to breaking down their opponents.

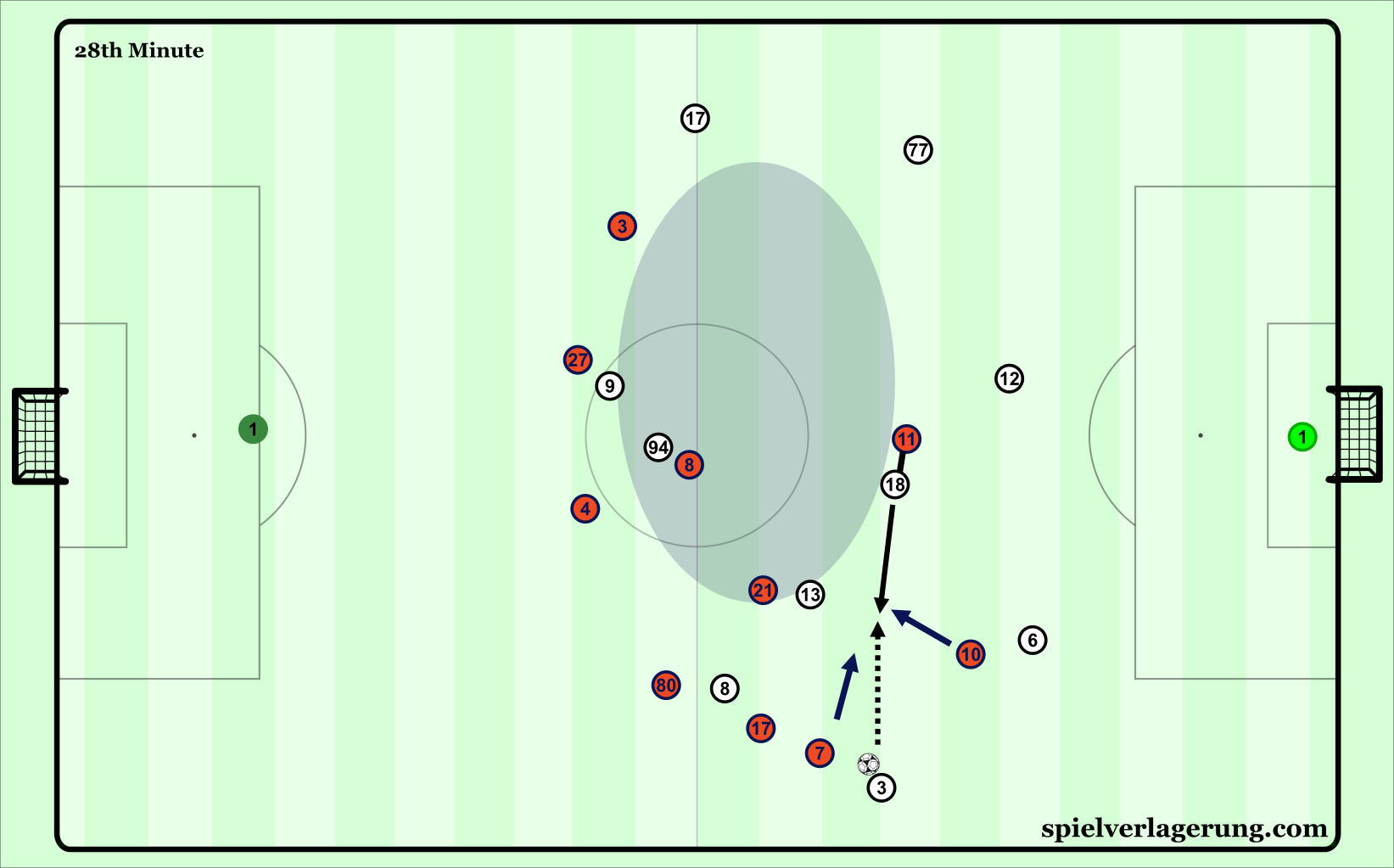

Because Talisca (#94) is too close to Negredo, Besiktas have few options to switch the play away from Basaksehir’s pressure forming on the left wing, where Adebayor, Visca, and Elia (now following Arslan) can pressure 3v1. This sequence leads to the lone goal of the match.

Istanbul’s pressure of the ball carrier also led to timid play from their opponent’s central players. When with the structural issues of earlier, Atiba Hutchinson and Arslan would end up selection easy options to pass out toward the wings instead of more threatening options central or even in the halfspace. Hutchinson consistently took excessive touches and Basaksehir were about to adapt their positioning in that time to prevent passes into attacker. The Canadian had the most passes on the pitch at the time he was substituted, but few of these posed a threat by themselves, rather they just consolidated possession and were not helpful for his team going to goal.

Consequently, Besiktas’ attacks were closest to scoring from the crossing that Gonul provided out right, aiming for Negredo just like their opponents did with Adebayor. Basaksehir physically had better defenders to deal with these crosses, since none of their defenders were as short as Medel is. In summary, Besiktas had difficulty navigating the pressure that Basaksehir brought to them, and despite having good attacking talent, there were a series of structural and cohesion issues that prevented them from beating the pressure in a more sophisticated way.

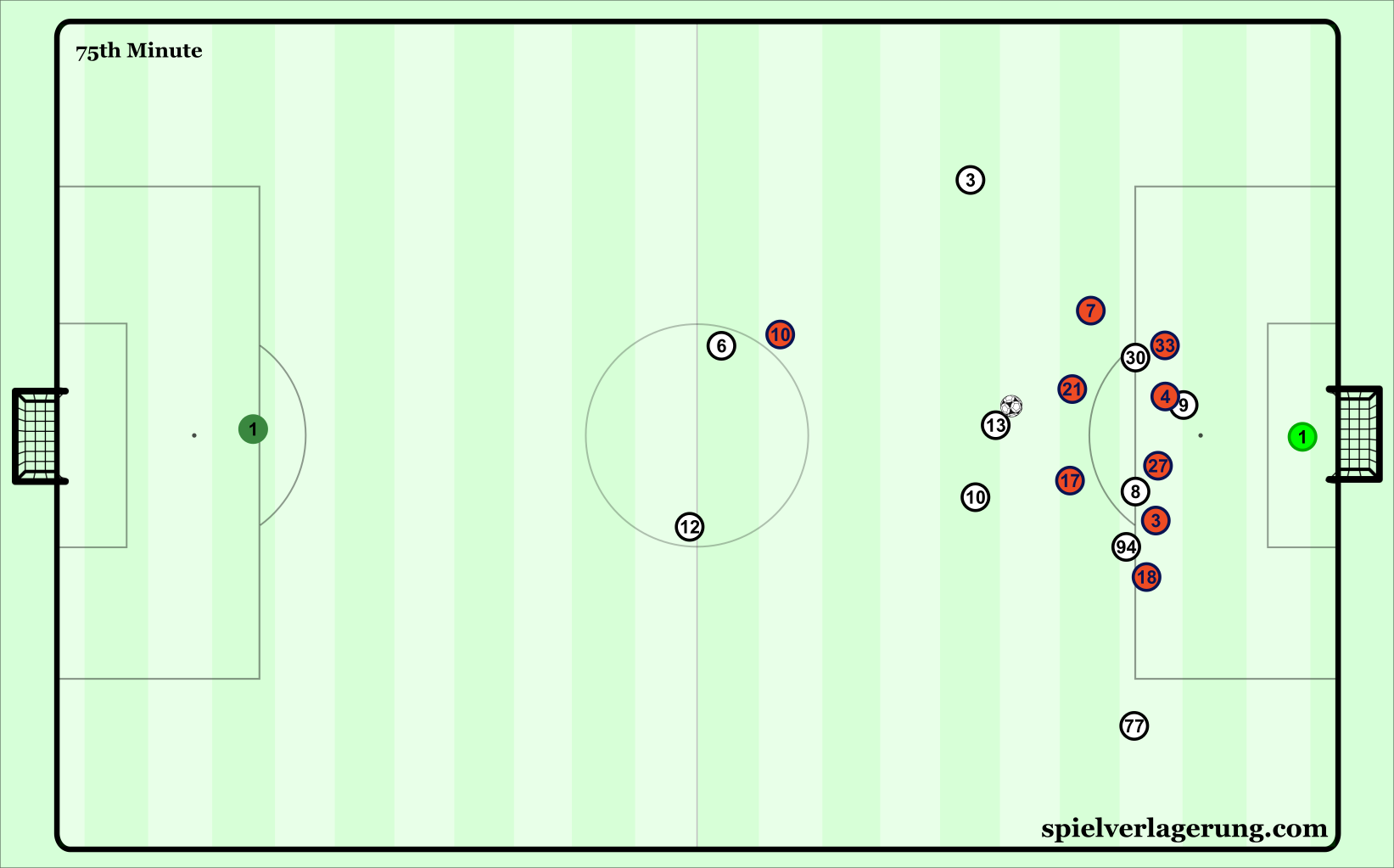

Down to 10 men

In minute 63, Junior Caicara was sent off for his second yellow card, changing the flow of the match almost instantly. No longer did Abdullah Avci have an interest in playing expansive, proactive football. Instead, he set up in a remarkably deep 4-4 block, at times taking on a 6-2 shape, leaving Adebayor up front to run onto any clearance and temporarily relieve pressure with his long dribbling seqences up the pitch. It might seem surprising, but Adebayor at 34 years of age was a continuous threat to run in behind Besiktas for the whole match, as they genuinely struggled at handling his marauding runs with the ball. His goalscoring form suggests he is experiencing a career renaissance here in Turkey, as he has logged many goals against the top teams in Turkey, not just the minnows.

The adjustments that Besiktas made had a minimal impact on the match. Bringing in Vagner Love and Ozyakup did not assist the last resort aerial attacking that was implemented for the last half hour. They did not provide strong solutions to breaking down the deep block of Basaksehir, right up until the final whistle. Despite winning the league last season, Besiktas were not prepared or equipped to deal with the centralization of Istanbul’s deep block, leaving them in third place in the table.

Conclusion

At the end of these fixtures, only six points separate these four teams from top to bottom, making this one of Europe’s most intriguing title races. Given that the top two teams earn qualification to the Champions League, Istanbul Basaksehir’s win shows that the there is a fourth Istanbul club to reckon with. While most of the big names appear to be talents of yesterday, the composition of each of these teams provides these talents a lot of freedom to work within, while giving strong promises of European competition in a country with passionate fans, making it an attractive option for some players.

Managerially, each team appears to be governed under similar principles, with not much variation was found between these clubs stylistically with exception for the newcomers. Istanbul Basaksehir are quite proactive in their approach and blend the qualities of their players really well to form an attractive, high intensity footballing side that is quite good in the collective. They will be interesting to watch evolve in the future as they seek to upset the Turkish status quo.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Ricardo Barros April 11, 2018 um 11:34 am

Benfica-Porto this sunday with whoever wins coming out on top highly favoured to win the Primeira Liga.

Would be very coll if you could have a look at that game, this is a quality article!

Cheers