SV Observatory – Volume I

We introduce a new series profiling matches in countries and leagues that are not frequently discussed on Spielverlagerung.

Before we delve into the matches, I’d like to establish what the idea was behind the SV Observatory. Spielverlagerung.com has a tendency to cover matches of the most well-known managers and clubs. Of course, we only select matches that appeal to us, but since we only have a finite amount of time, those oftentimes end up being matches seen by millions across the globe. These matches represent a very small portion of the professional football landscape. Since the turn of the new year, we have covered matches and clubs from only 5 countries, with an interview from a professional from Denmark making it 6. Given that football is played all across the globe, I hope this series begins to offer some additional insight as to how the game is different in various parts of the world. These observations are from a distance however, so they might be lacking some more in-depth context that is found in other analyses.

Spielverlagerung.de has something similar written by the godly TR (this is filled with excellent profiles of many relatively obscure matches, players, and coaches), and if this can even be half as good as what TR does, I’d be the happiest analyst in the world. To start us off, we go through Willem II, Benfica’s win vs. C.D. Aves, finishing with a footballing tribute to one of humanity’s greatest minds.

PSV Shocked by Willem II (+ III)

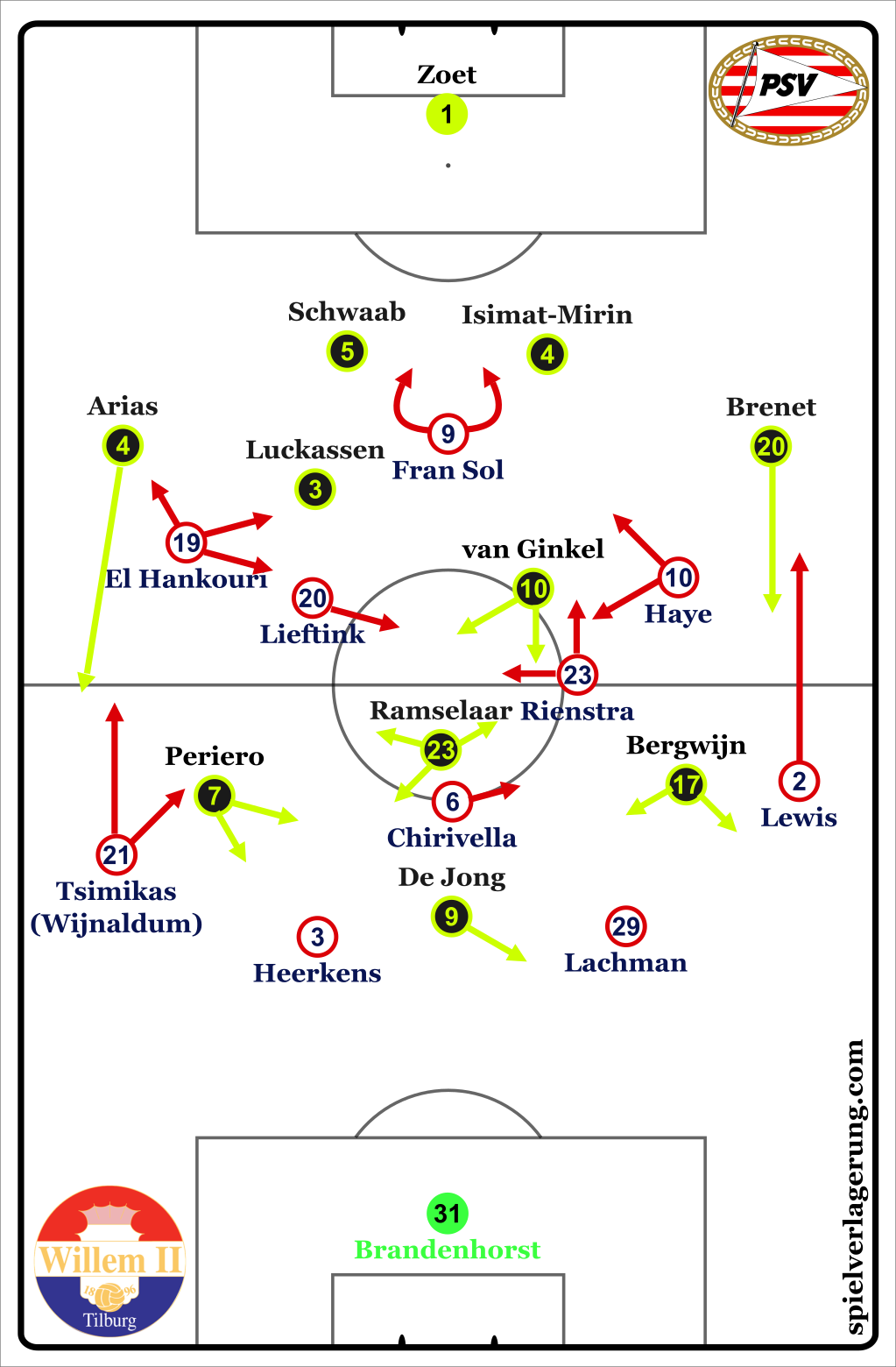

Only two days before the match, Willem II fired their manager and appointed assistant coach Reiner Robbemond as interim manager. In his first match in charge, he managed to defeat the comfortable league leaders by 5 goals, inflecting PSV’s worst loss in the league in over 50 years. Such a scoreline was not the cause of a genie in a bottle; rather, Willem II demonstrated electrifying attack play in an ultra-dynamic 4-3-3 base, causing PSV to bunker at times to cope with the speed and intensity of combinations and runs. Since both teams aimed to attack with speed and also defended deep, the match was entertaining viewing from a neutral perspective.

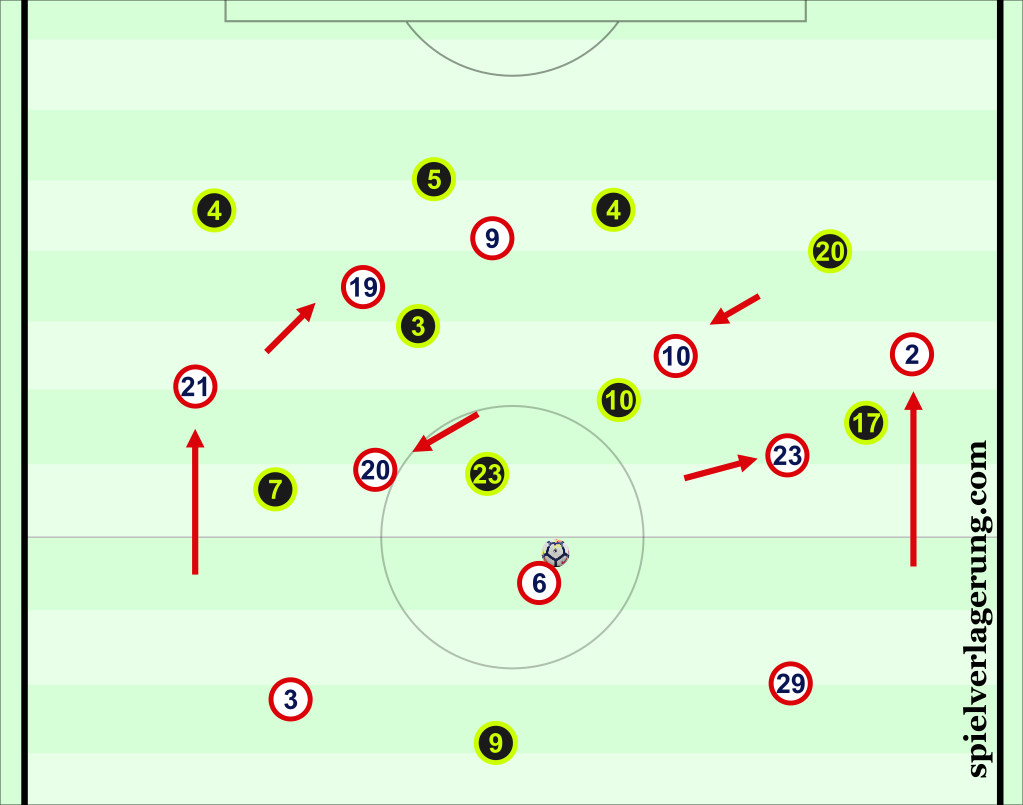

Willem II had a starkly interesting attack set-up, elegantly combining somewhat complex attacking dynamics between players within a rather simple tactical framework. 4-3-3 base wasn’t really ever found in their attack, as each side underwent interesting interactions in the right and left side respectively. On the right side, the fullback would push remarkably high, with Rienstra staying slightly wider to provide transitional cover. Haye would drop into traditional centre midfielder spaces or alongside Fran Sol as an immediate lay off option in case the ball ended up at the former Villarreal player’s feet. Rienstra would move forward to look for cutbacks when Lewis was threaded through balls into wide spaces in behind, an occurrence that happened frequently during the match.

Fernando Lewis was the most impactful player to Willem II’s system by some margin. First of all, Lewis is remarkably blessed physically when it comes to his speed and was in impeccable fitness. This allowed him to run up and down the right wing and cover a great deal of distance during the match. Secondly, with the numbers advantage formed thanks to the quasi-overload rotations on the right side, a free player was usually available for possession because of PSV’s late reactions to adjusting their man-orientations. This free player would aim to find Lewis running in behind Brenet on the right wing.

Lewis was excellent in how he timed his runs, starting his runs from 5 to 10 meters away rather than higher up the pitch. This gave him a head start to his runs, referred to as a dynamical advantage. By the time Brenet could turn his body and begin tracking him, Lewis had already reached a speed where he could not be caught. This pattern resulted in the most dangerous sequences for Willem II and the first three goals, emphasizing how difficult Lewis was to handle.

On the left side, El Hankouri remained permanently closer to Sol in the left halfspace, and the attacking behavior was slightly different. Lieftink operated slightly more defensively and would veer closer to Chirivella while Tsimikas replicated Lewis’ attacking patterns on the left. Rather than use the speed and timing advantage that Lewis brought to the right side, Tsmikas was better with shorter play in tight spaces and both him and El Hankouri used pauses of the ball to allow PSV to compress onto them, opening up space to either overlap or centrally to open the attack. With PSV’s man-orientations, Willem were skillful in using these movements on the left side to play into valuable spaces for their attack to operate, as PSV could not shift in time to cover wing runners or newly freed options in the centre.

Willem II have made good use of their borrowed talent. In the starting line up, their left back and winger are owned by Olympiakos and Feyenoord respectively. One player that stood out was Pedro Chirivella, the holding midfielder owned by Liverpool. Only 20 years of age, Chirivella was the most press resistant player on the pitch, demonstrating several clever solutions out of PSV pressure (which wasn’t convincing in the first place) and upon winning tackles or interceptions, finding players with his passes that could begin attacks immediately. Chirivella with some growth to the physical and tactical side over the next years has the potential to be a member of Liverpool’s squad, but may lack the profile to fit into Klopp’s team at the moment. The former Spain U-17 international is a bright prospect for the Reds to keep tabs on for future openings in the roster.

As impressive as it was to watch the young team from Tilberg run riot on the league leaders, the equally youthful PSV had some glaring issues of their own. Besides the unnecessary direct play seen at times from Cocu’s men, the lack of counterpressure once possession was relinquished was glaring and the biggest reason for the rout. Since Willem II stepped up to close passing lanes as PSV players dribbled forward, they had many interceptions where they were able counter quite easily because of an unbalanced structure in attack from PSV. The midfielders frequently lost the ball during early phases of their attack construction, leaving the wingers too high up the pitch to contribute to counterpressing because of the large distance.

They were missing Hendrix and Lozano, two of their biggest players, so it can be partially be attributed as an off night for PSV. However, Cocu’s change to take off Arias, the brightest attacking threat from fullback, did not win any territorial advantage for PSV. Combined with reactive disposition of Cocu’s team, PSV showed little impetus to establish themselves in the match. Due to their fragmented pressing, Willem II pretty easily imposed their style of play on the match. Despite the talent edge that PSV possess, their system seems dependent on the qualities of individuals like Lozano or Hendrix, and missing the cohesion that each of them brought.

In summary, Willem II impressed with the interim boss in charge, implementing fairly simple tactics with great effectiveness. The next matches should be interesting, as they could either have the new manager effect wear off or develop into one of Europe’s most interesting sides not fluttering near the top of their country’s table. As for PSV, despite their domestic success over the years, this result appears to be a indication that Cocu is a great manager at keeping a lead, but not regaining one.

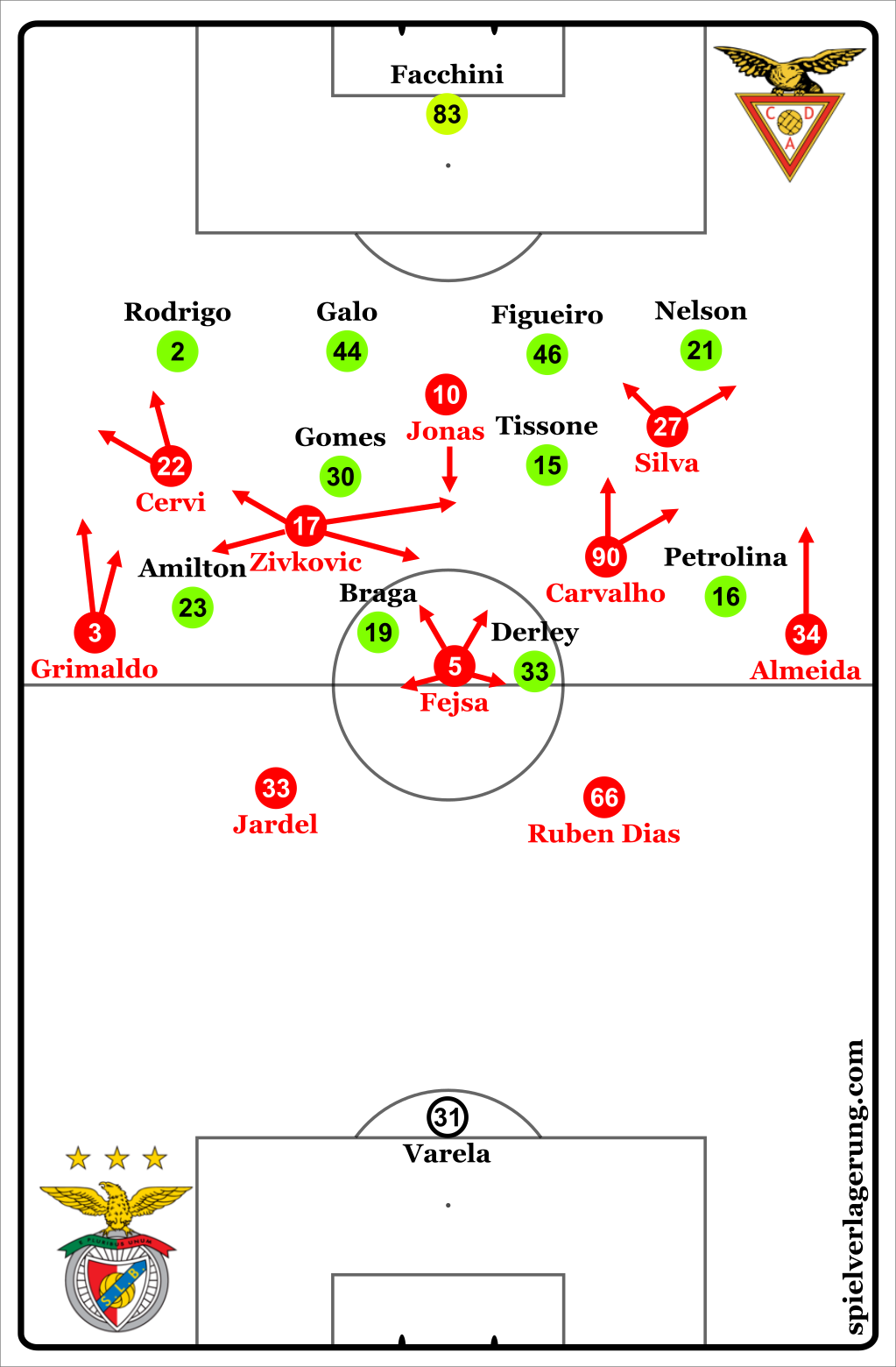

An Ornithological Match in Lisbon

The battle between birds. SL Benfica hosted C.D. Aves in a routine league win, but it was a cagey affair that almost saw Benfica unable to break through Aves low block. However, fittingly enough with the match up of club crests, this game was heavily influenced by the play on the wings, where a wide variety of player rotations were seen from Benfica. However, it was to the detriment of their attack as a whole, as the wing focus drove players out of the centre, only to be corrected by an aerially focused substitution in the second half.

Considering Aves were in a deep defensive set up that was focused on compacting the centre, Benfica had their main advantages in the wide zones. Aves were in a 4-4-2 against the ball, so moving central midfielders into the wing areas would create an extra player if he was not followed right away. The away side however was adaptive when it came to adjusting their coverage and pressure, frequently picking correct moments of when to leave a player in coverage in favor of pressuring the ball carrier.

It didn’t help Benfica that dribbles toward the wing were ineffective, as Aves defenders intelligently adjusted their orientation to force them down the wing, alongside providing coverage centrally to have a second player pressure when the first one was beat, or even to double up the player with the ball and force an error. Benfica’s attackers were guilty of taking too long with their decision making in the early stages of the match, leading to failed combination play down the wings alongside final third play that was fruitless because of Aves’ admirable reaction time to reorganizing their defensive positions once lines were broken or pushed back near their own goal.

The left of Benfica had the most interesting developments during the match, thanks to the versatility and understanding between Grimaldo and Zivkovic. The former Partizan captain had the most positional freedom of anybody on the pitch, frequently drifting over the right side in one minute and in the next minute, being the widest player on the left. Due to his qualities of creating passing options using feints and separation dribbling, he was the main key that could unlock Aves’ door. Most of the moments of highest quality came when Zivkovic limited his touches, with local options surrounding him playing quick wall passes to advance into the attacking third of the pitch where individualism was liberally forgiven by manager Rui Vitoria.

Grimaldo showed variation in his movements forward that make him an attractive option for playing other positions if possible. His underlapping movement and interior dribbling is reminiscent of David Alaba during Guardiola’s Bayern tenure. The only problem that came with this was the fact that the centre was effectively vacated besides Jonas, who offered little spatial creation as the furthest player forward, and Carvalho was covered out of the match due to his excessive loitering the right halfspace.

This central occupation issue was fixed through the substitution of Carvalho just before the hour mark in favor of Raul Jimenez. The Mexican pushed Jonas into the ten to provide more of a connection between the deeper players in the team and the space in front of Aves’ centre backs, putting the visitors on the ropes as they aimed to get territory higher up the pitch. Thanks to their defensive structure, alongside their overly aggressive goalkeeper, Benfica adjusted their strategy as a whole to play passes in behind or cross in such a way that Facchini came out with fervor to manage the attacking threat. With corner kicks, they did by playing inswinging balls to the back post that landed just at the far corner of the six, so that Facchini would be a state of purgatory during the flight of the ball as to whether he could get it or not.

Jimenez was the keystone when it came to the increased success of Benfica’s attack in the second half, as the aerial presence he brought led to the centre backs having an increased focus on him. Due to the new division of concentration, other attacking options on either side of the defenders were neglected. On both goals of Benfica, the players that were previously covered in these zones before Jimenez entered the match scored following shots that were deflected or rebounded, highlighting how the number 9’s impact on the match, while not showing up on the scoresheet, can in the form of altering the way that Aves covered Benfica during their attacks, which in itself led to the goals.

In Memory of Stephen Hawking: A Brief Discussion on Entropy in Football

One of the world’s greatest scientists has left our earth, as Stephen Hawking has died at the age of 76. It is difficult to not have some admiration for those who advance knowledge to the scale that he did, doing so while being told he had two years to live at age 21 because of ALS. Some of his most transformative work was with black holes, changing the understanding of the known universe and increasing the amount of interest and exploration on the subject. One of the areas Hawking extensively studied was the role of entropy in black holes, and whether or not it can exist given event horizons where no light can escape. For those who do not have much understanding in physics, entropy simply refers to the level of disorder within a system, typically in the context of energy that is unavailable to use. This provides a decent (and less technical description) of what entropy is scientifically if you’re interested, but for now, let’s equate it with disorder.

Football may seem like a black hole if your team gets knocked out of the Champions League or gets relegated, but that’s where the similarities end. With the exception of entropy. If we view a football match as a closed system, the level of disorder that takes place during the game increases over time. This can occur for multiple reasons, as there can be injuries, fatigue manifesting itself through the match, red cards, among others. This increasing of disorganization is inevitable. For anybody who has played even an hour of pickup football, there’s probably been a match where the game stretches out and can seem like a fragmented bunch of players, with some players only electing to defend, and others only electing to attack.

For the sort of matches that we discuss on this website, the comparative level of collective entropy is quite low. With each marginally decreasing level of play, the starting point of entropy alongside the rate of how entropy increases also increases, down to the lowest conceivable level of football you can imagine. However, disorder will still increase as the time frame of a match goes on because of the limits of the human body.

As a coach though, it is one of the responsibilities to bring order among so much disorder, instilling order in terms of principles of play, pressing schemes, specified areas for positioning, automatisms, and whatever the coach feels is appropriate for their coaching style, effectively their version of order. One could argue that the best coaches and their staffs, regardless of style, are the ones that are able to instill this orderliness the best. First off, they have sports science and fitness staff to limit the roles of fatigue and injuries in a given match, week, or season, which aims to limit the role of entropy on the amount and quality of football actions in a match. Additionally, Coaches will train with the chief goal of limiting (or optimizing) the level of disorder among player interactions. The faster and more synchronized the parts move within the eleven players, the more effective execution will be, unless they face a team prepared or suited to defeat their orderliness. Levels of organization that a coach implements in all phases, whether it be in attack, transitions, or even off of throw-ins, represent an increasing sense of orderliness in the game. They are prepared for anything and less likely to have large changes in the match entropy affect them.

From a planning perspective as a coach or strategist, it is their responsibility to best manage the levels of entropy throughout the match. This can be used to find avenues for their players to win or develop, whatever the goals of the trainer may be. In a match example, a worse team may aim to have the game be as disorganized as possible by peppering the opponent with long balls, as an organized game could give their superior opponents the edge in possession and cater to their team strengths. Alternatively, a substitution that possess good counter attacking abilities and speed that enters in minute 70, with the purpose of taking advantage of the opened spaces and depleted fitness levels of the opponents, which one might call entropy. Developmentally, having a team play up an age group will create disorder among players that they must solve problems at a faster speed in order to improve as individuals. On a similar note, Spielverlagerung author AO talks about how one can coach chaotic situations with our friends at KonzeptFussball.

Strategically, many plans are designed to exploit weaknesses of the opponent, which one might call a state of disorder. One can re-frame the way think about their strategy, making it not so about about absolute strengths and weaknesses, but in terms of entropy. The goal is to maximize the opponent’s level’s of disorder, while minimizing the ways the opponent will disorganize your team. The best coaches in the world display this with their teams regardless of environment. How exactly that’s done is the intersection between the art and science of coaching.

Conclusion

Coincidentally timed with the passing of one of the most iconic astronomers, a space-inspired series is introduced aiming to explore the depths of football that are not often discussed. An observatory was the most fitting analogy I could think of, as there are so many football clubs and teams out there, sorting through them all to decide is interesting to discuss feels like searching for particular stars and galaxies. It could also be possible that the observatory spotlights a future star in management or on the pitch, so that double entendre was impossible to ignore. But for now, the aim is to increase the understanding of the beautiful game as it is played all over the world, not just in vacuum of the highest levels.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen