Interview with Schalke head coach Domenico Tedesco

For the first time, Spielverlagerung had the opportunity to interview a current Bundesliga head coach. Schalke coach Domenico Tedesco talks about the tactical evolvement of his players and how he involves them in his tactical planning.

Meeting in Gelsenkirchen. Michiel de Hoog of the Dutch website De Correspondent is researching for a story on the young generation of German coaches, who have been called ‘Laptop Coaches’ by some. He wants to know why young outsider without a history as professional players get the chance in Germany, but not in the Netherlands. What’s better than to visit Schalke 04, where sporting director Christian Heidel gave a 32-year-old newcomer the keys to the kingdom? When Michiel meets said newcomer, our author TE accompanies him. We would like to learn how important tactics is in the eyes of Domenico Tedesco, and how he equips his players with the necessary knowledge.

Mr Tedesco, we brought a video from the match against Freiburg with us. Here’s a scene showing the defence.

Tedesco watches the footage and smiles: Nice. Beautiful shape.

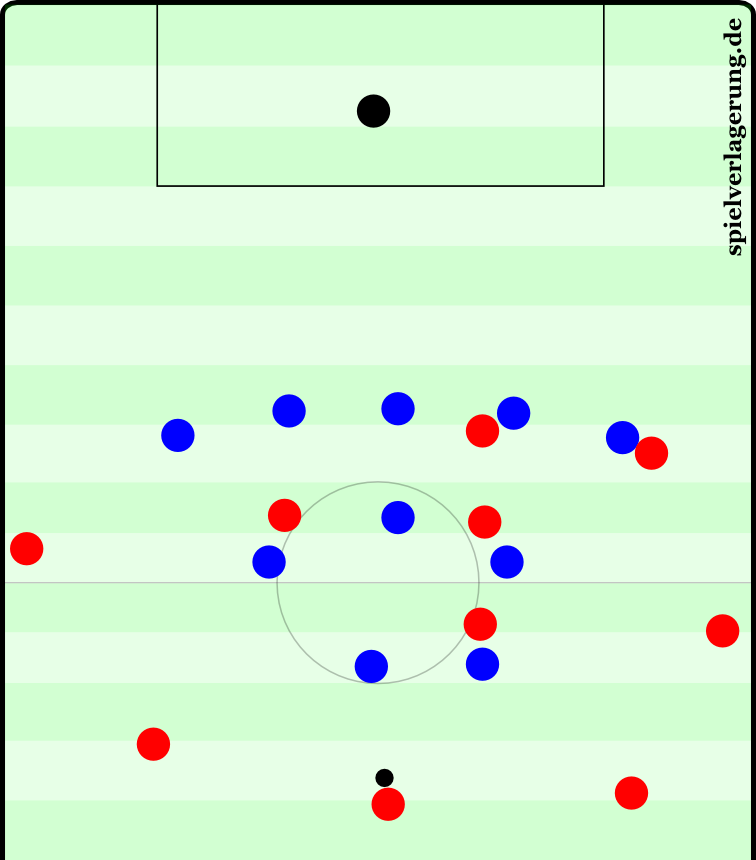

This the mentioned scene during the match between Schalke and Freiburg. Freiburg wore the red jerseys. We showed Tedesco a video which we can’t show here due to copyrights.

How do you manage that your players are positioned so perfectly?

Tedesco: First of all, it takes a lot of practice, particularly from the players. Practice, practice, practice, studying video footage, and then, again, practice, practice, practice. The most important thing is the work you put in on the pitch. If the players are supposed to stay within the formation, you need a few pillars. You need someone at the back who keeps an eye on the position of the line. Attackers who decide when to press. Centre-midfielders who say: ‘When do I advance?’ There are three, four communicators who have to manage it. The staff talks about it with the players. And, at the end, it hopefully ends up looking like that scene.

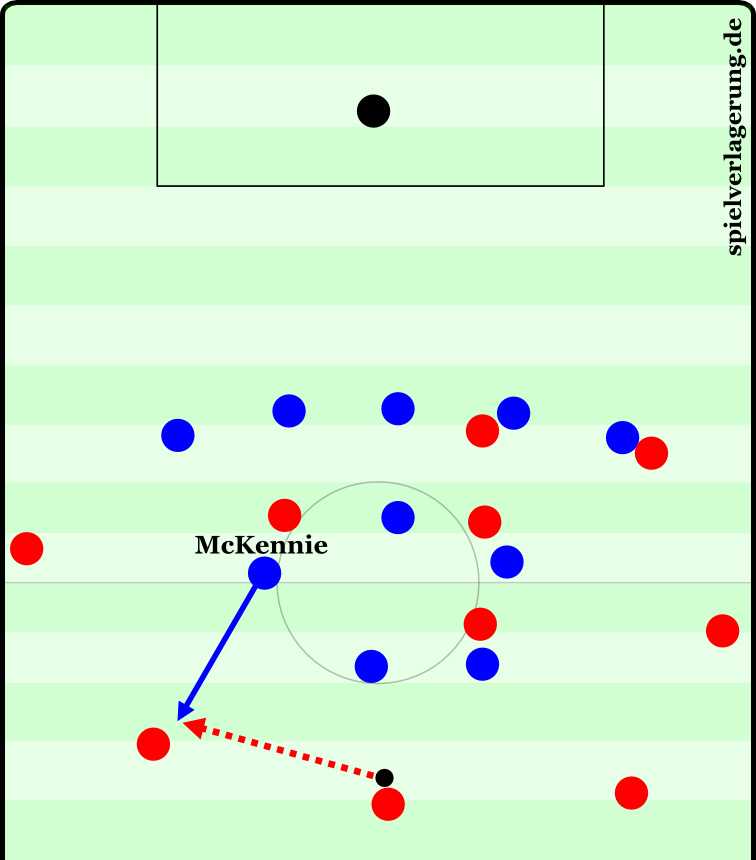

When we fast forward a bit here, we see Weston McKennie advancing and transitioning into pressing. That happened multiple times in that game. Do you talk about something like that beforehand or do the players make the decisions on the fly?

Tedesco: We talk about it beforehand.

How detailed are the guidelines?

Tedesco: It has to be clear which player in which situation does the transition. What’s the pressing trigger? Which passes made by the opponent should be recognised as a signal? For instance, there are opponents who use two centre-backs who are positioned wide. When these two play the ball to each other, the ball is moved over a relatively long distance. That means the ball is loose for some time. [Tedesco claps his hands.] These are the best moments to pressure.

And these pressing triggers are different for each opponent?

Tedesco: We have general triggers, but these vary heavily from match to match.

Back to that scene: What we found intriguing in this context was the press conference prior to the match against Stuttgart. You explained that players had too often blocked the opponents but had not advanced within the process of pressing.

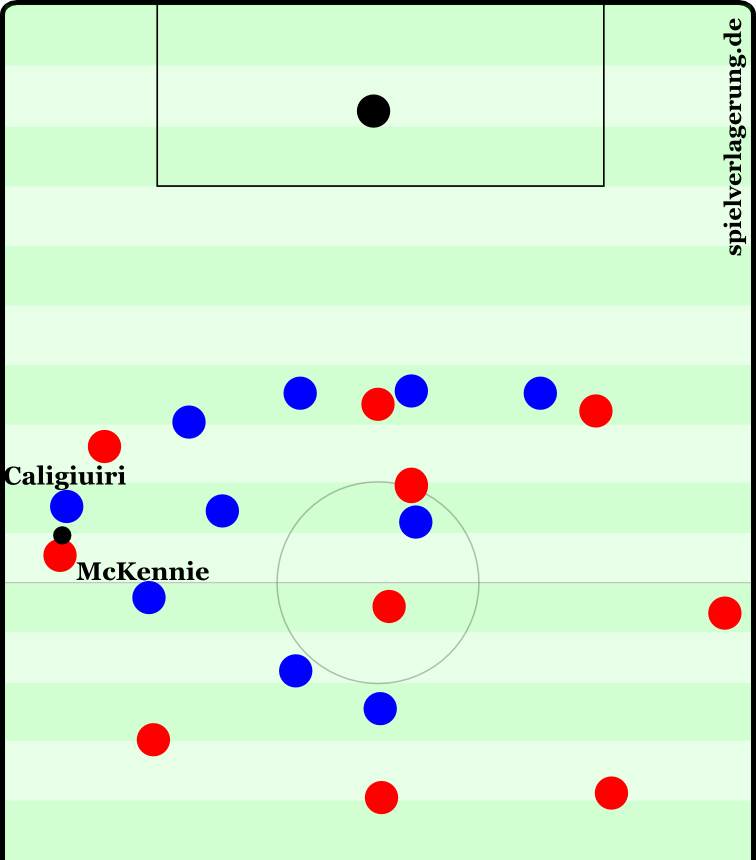

Tedesco: This scene right here is a good example. Daniel Caligiuri ran through. But against Stuttgart, for instance—there were other matches, but particularly against Stuttgart—we just blocked in those situations. [Tedesco stands up.] Blocking always means they have the ball and I don’t let them pass. I show them one side; can lead them outwards or inwards, depending on your philosophy. But that’s a huge difference. If I just block them, they have more time to make a decision. If I block them constantly, then the opponent play the ball backwards. Then the next one goes forward, and the opponent play backwards again. That’s just passive. You can do that. There’s the philosophy of sitting deep. However, there’s also a difference between sitting deep and shutting down passing lanes, on the one hand, and a deep press on the other. Sitting deep means I just shut down passing lanes. But when using a deep press I shoot forward frequently, just like forechecking in ice hockey.

The final phase of the scene. Caliguir ran through and forced the opponent to play a pass under pressure. The ball ended up in the hands of Schalke.

And that’s what the players were struggling with early on in the season? You said rather underlying reasons caused that.

Tedesco: The players can execute it. But there are these moments when they think they should shut down passing lanes.

Is that a specific issue for some teams, or specifically a German issue, or do all players have that tendency?

Tedesco: I believe intensely trained patterns are in the heads of all players, in Italy or the Netherlands, too.

But why? Because it can be executed more easily?

Tedesco: Running through is exhausting. When you run through, then it gets intense. Then, sometimes, it may happen that opponents play the ball backwards and I have to break up the pressing and move back. That hurts.

We all know the feeling. It is less exhausting to block the opponent. And all have to do it so that it can work.

Tedesco: Exactly.

But how do you train that?

Tedesco: We train ‘forward defending’ a lot. You can even train it when playing handball-header. [Handball-header is a typical warm-up exercise in which the players are supposed to play the ball with their hands so that one team-mate can head the ball.] If you play it as usual, then the defenders stop right in front of the one who has the ball and flutter with their arms, just like in basketball. Now you should apply the rule saying if I touch the player who has the ball, I gain possession. Then the players run through.

That’s almost training on the neurological level, as you have to reprogramme your players.

Tedesco: Yes, we would like to be courageous. Daniel Caligiuri doesn’t win the ball here; he doesn’t have to. But he makes sure the opponent has to play the ball faster, and look what happens: loss of possession. If the opponent has enough time in this situation, he will see an open team-mate, who then finds the next open team-mate, and so on. In the Bundesliga, all players are of high quality. Giving them time means they will make good decisions. We want to take away the time.

Do your players manage to do that now?

Tedesco: I think we do that quite well. We have to continue practicing it. It’s a process which never stops. You have to repeat it again and again. You need energy, stamina, you need courage, be ready for sacrifice.

This topic reminds me of a chat with a former Bundesliga player. He often played as a no. 8 in a diamond formation. When the full-back received the ball, he had to advance and pressure that full-back. He almost never won the ball. He hated it.

Tedesco: If you are one of the midfielders within the diamond, you have to do it, though.

Alright, but how do you as a coach make it clear to him that when he makes the run for the one-hundredth time he knows it is not pointless?

Tedesco: That’s the point. You need the right feeling for it. What type of player is he? Can he do it? Or does he waste too much energy which he needs in attacking situations? Can he compensate it in a different way? [Tedesco is about to explain it.]

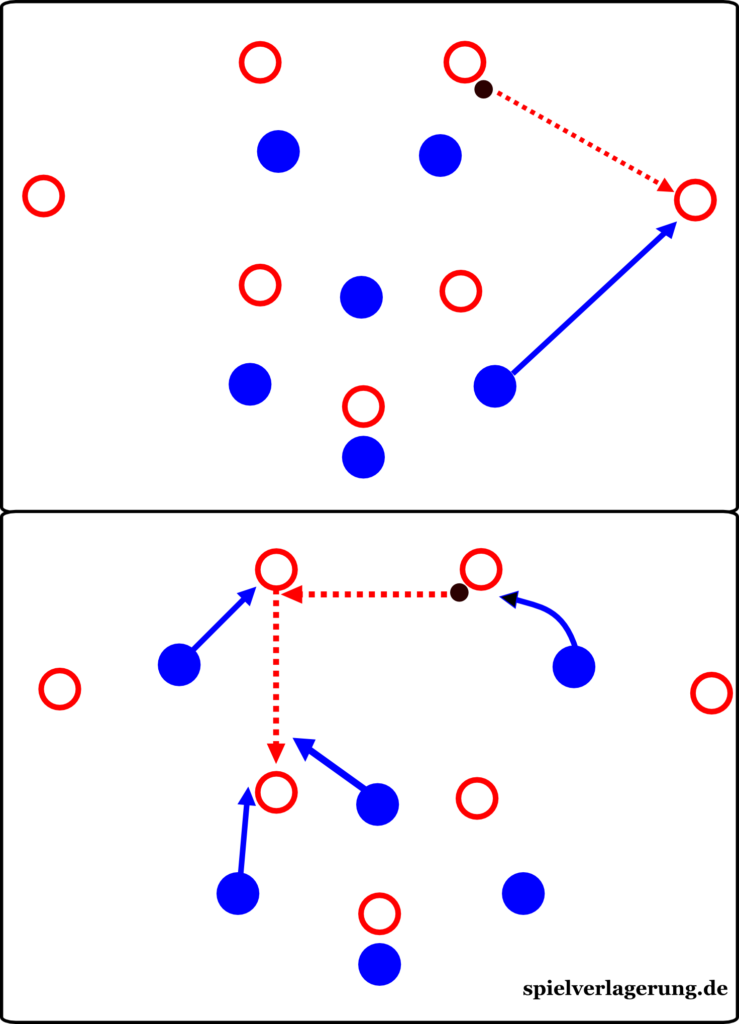

This is the situation Tedesco explained. The top picture shows the traditional version: The no. 8 runs towards the full-back. The bottom picture shows Tedesco’s idea: The forwards cover the passing lanes to the full-backs, forcing a lateral pass between the centre-backs. The second forward starts the run and increases the pressure to act. The no. 10 tries to intercept a possibly misplaced pass which can happen under pressure. The no. 8 immediately attacks the no. 6, in case he receives the ball. (Tedesco additionally explained how a team can defend the extremely difficult pass from the no. 6 to the full-back. The no. 8 could run through until he is close to the full-back. He would pick up enough speed and would not have to change his direction much.)

One moment, could you draw it, please?

Tedesco: You have got two strikers and the diamond. Now you could say: If the ball goes to the full-back, your player always has to leave the diamond. Makes sense, because in the middle you got four players, and the opponent usually has only two or maybe three. You can make up for it in the centre. However, you could also tell the striker: stand right here. And when the ball is being played, then he is in the cover shadow. Then he usually plays the ball back, then the next striker moves. Or he plays it to the no. 6, and we have our no. 10 and two no. 8s there.

Christian Heidel said that you are very good at involving players in your tactical considerations. Do you sit down with the players and explain them your ideas just like moments ago?

Tedesco: Yes, regularly. The players are the ones who have to understand and execute. Back to your example: You are my no. 8. Always, when the ball goes to the full-back, the no. 8 has to move towards him. I could tell you, that’s my plan, full-stop. But now we have practice and I realise they do it the first time, the second time. When it comes to the third time they start gasping, and after the fourth time they had enough.

Not because of exhaustion.

Tedesco: No. Simply because they can’t be bothered. When I tell them we do this during the match on Saturday, then I know after 20 minutes, it won’t work. I can already see it in training.

There are coaches who think about it the other way. They would say the players have to get over it.

Tedesco: If I see something like that, I ask the no. 8: ‘What’s the problem.’ ‘Coach, the distances are too long.’ And now we are in a discussion. Now I can say: ‘Alright, then position yourself a bit wider.’ Then he tries that twice and says: ‘Coach, that makes no sense.’ Then I ask again: ‘What’s the problem? Perhaps the striker can help you, so you don’t have to move there in every third case, just in every fifth.’ And that’s how we try to develop an idea together. That’s important, because if a player says ‘yes’ in training, it has to be a ‘yes’ in the match as well.

That means?

Tedesco: Tactical training, which means we watch video footage and then practice it on the pitch. Afterwards, I always ask: ‘Do you feel comfortable with what we have prepared? Are you able to execute it?’ If they say ‘yes’ … [Tedesco bangs on the table.] then I will take them at their word. Then it has to work during the match. If it doesn’t work during the match, because the opponent did something differently, it’s not an issue. Then we coaches have to come up with new ideas and react. But if the opponent plays the way we expected and we don’t execute it properly, I’ll ask the next day: ‘Why didn’t it work? What was the issue?’ And that’s how we evolve. The players, however, have the chance to say: ‘It doesn’t work, we need a different idea.’

Does your staff talk to each other using different verbiage than with the players? Or do you use the same terminologies like ‘cover shadow’ in the presence of the players?

Tedesco: The same terminologies.

The players do understand it?

Tedesco: Yes, nowadays they do. A lot hasn’t been invented from scratch. ‘Cover shadow’ exists for what feels like a million years.

Well, we know enough people who don’t know the term. We appreciate your time, Mr Tedesco.

Tedesco: Thank you.

You can find the original interview which was conducted in German here.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Preston May 16, 2018 um 2:21 am

Great piece, I found the interview fascinating

Konsta February 3, 2018 um 8:06 am

Thank you very much, that was absolutely fascinating.