Aspect Analysis: Dortmund’s build-up against Bayer Leverkusen’s pressure

In-form Borussia Dortmund faced not-so in-form Bayer Leverkusen on Saturday. Schmidt’s team were coming on the back of two consecutive losses to Mainz and Atletico, while his hosts had finally overcome their goal-scoring problems with wins over Wolfsburg and Freiburg.

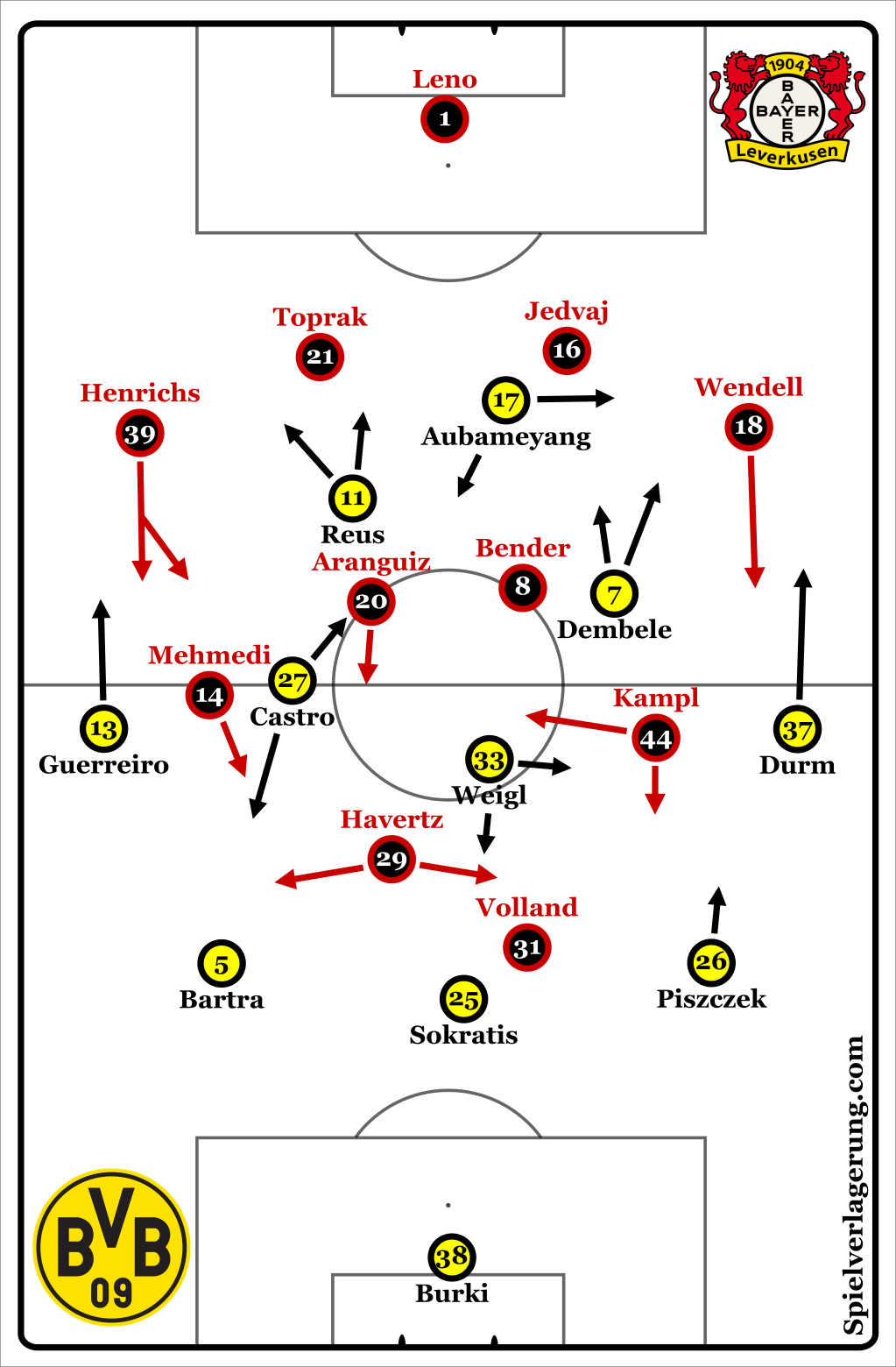

Dortmund lined-up on paper as a 3-1-4-2, but due to the asymmetry of their midfield, spent more time in a 3-2-4-1 shape with Castro acting deeper and Dembélé higher up. As ever, Leverkusen operated in their narrow 4-2-2-2 shape. Despite the crazy scoreline, the match didn’t offer many interesting features aside from the battle between Dortmund’s build-up and Bayer’s pressing game. As a result, this analysis will focus on this moment of the game, exploring how Dortmund effectively navigated the press, leading to a number of promising situations.

Base Structure

An important phase of the game were the moments during Dortmund’s build-up. The home side were tasked with safely advancing through Leverkusen’s aggressive pressure, while Schmidt’s eleven would be hoping to create chances through their efforts. In order to overcome their opponents’ aggressive strategy, Tuchel came-up with clear methods of advancing the play.

Their structure of a 3-2-4-1 posed issues for Leverkusen in all areas of the field. The additional player in the first line reduced Bayer’s access to press, and Dortmund benefited from a half-space to half-space coverage which allowed them to switch rather effectively. The deeper positioning of Castro created a dilemma for the visitor’s central midfielders, too, as an advanced position to access BVB’s ‘2’ would give Dembélé and Reus – two extremely dangerous forwards – space behind.

Due to Leverkusen’s heavy presence in the centre of the pitch, teams often resort to advancing through wing-play then attempt to bring the ball diagonally back inside. Dortmund were no different, and their strategies could be divided between the two flanks, where they used an asymmetrical shape to create space behind the press.

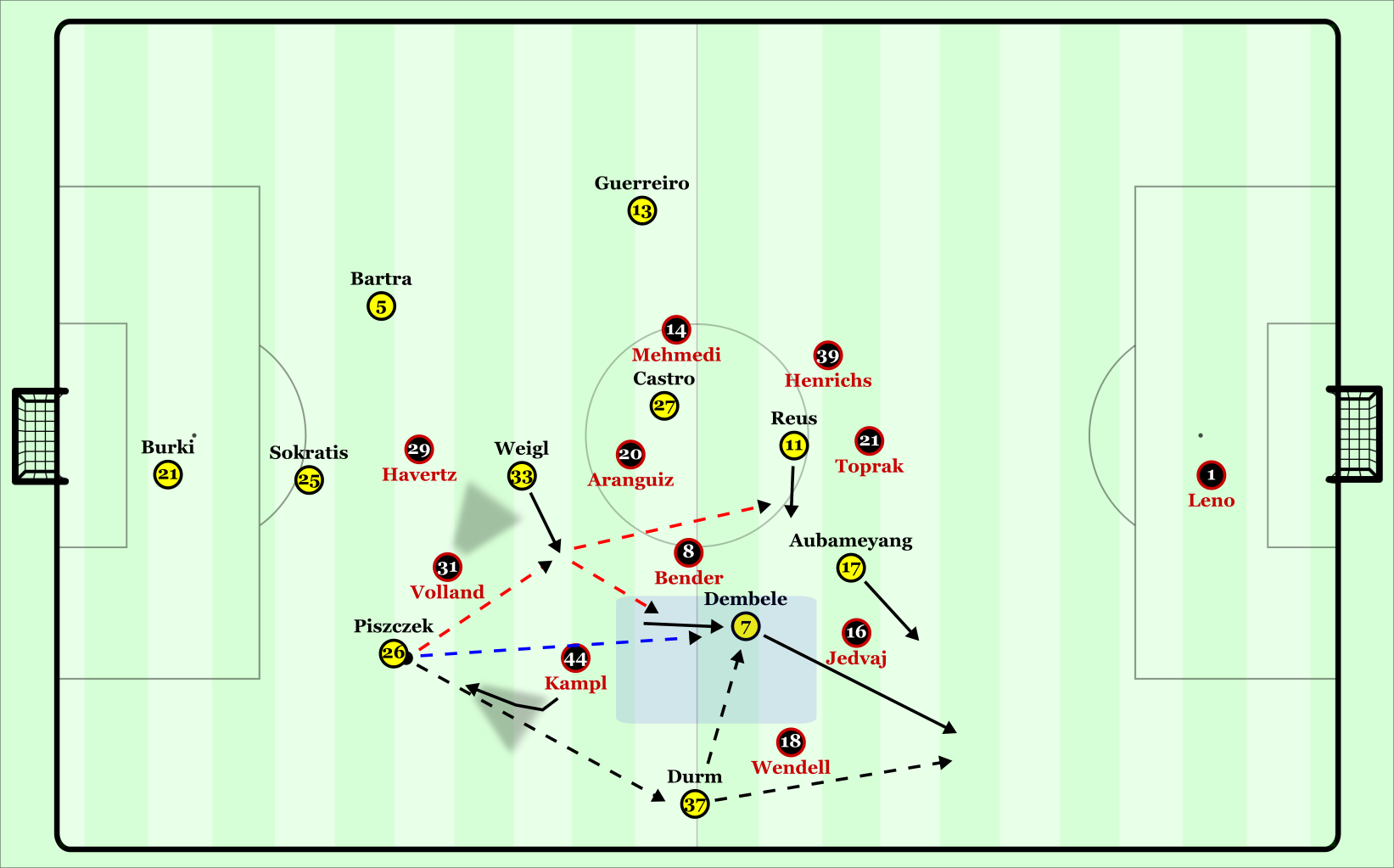

Left-Sided Build-up

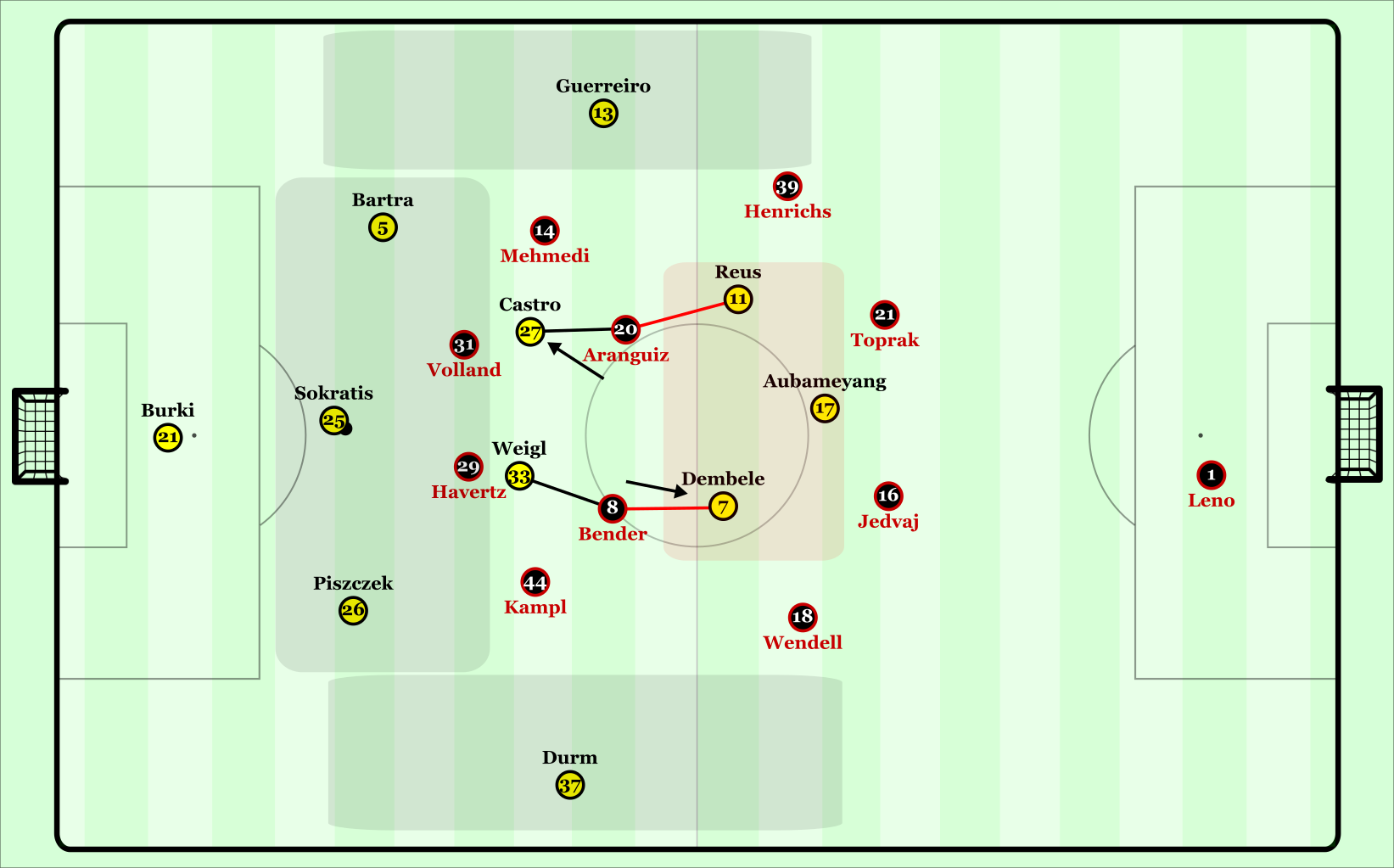

As normal, Julian Weigl maintained a fairly fixed position in the centre of the build-up, but to the left of him, Gonzalo Castro was more engaged in early possession than usual. The former Bayer player would drop in spaces around the left half-space, and in doing so attract attention of multiple pressers. His gravity could be enhanced through a simple exchange with Bartra – when receiving, Castro would be instantly rushed by at least two players, thus a simple wall-pass would theoretically give Guerreiro more space to use.

In coordination with Castro’s dropping movements, Reus would directly attack the left side of Leverkusen’s defensive line through runs into the channel between Henrichs and Jedvaj. This would restrict the right-back’s ability to access Guerreiro during build-up, with the worry of being caught behind by the recently on-fire Reus. While the forward was making runs in behind the defensive line, Aubameyang would make the opposing movement. The Gabonese striker would drop away from the defensive line and into the ball-near half-space, to cause further confusion amongst their opponents’ defensive line and increase the BVB presence between the lines.

Both Castro and Reus’ roles were firstly tailored towards Dortmund advancing through Guerreiro on the touchline. Castro’s presence in Dortmund’s left half-space demanded the attention of Mehmedi, while Reus’ direct runs prevented Henrichs from closing his opposing wing-back down.

When Guerreiro received the ball, he was composed against the inevitable diagonal pressure against the touchline. The EURO 2016 winner would look to diagonally play the ball back inside and behind Leverkusen’s midfield line, often through the dropping Aubameyang or occasionally Dembélé. The activity of Reus and Castro was important in opening up space diagonally for Guerreiro to play inside, as their occupation of Henrichs and Aranguiz respectively created this pathway against Bayer’s diagonal pressing structure.

This strategy led to the opening goal of the game, scored by the young French winger, who has made a more inside position his home. Although it came in a rather random succession of loose balls, the diagonal direction of play from Guerreiro back inside was evident. Albeit luckily, Dortmund did well to expose the issue of Bayer’s heavy ball-orientation. If they fail to sustain access, or in this case have unlucky breaks, then the opposite side of their shape can be severely underloaded and open.

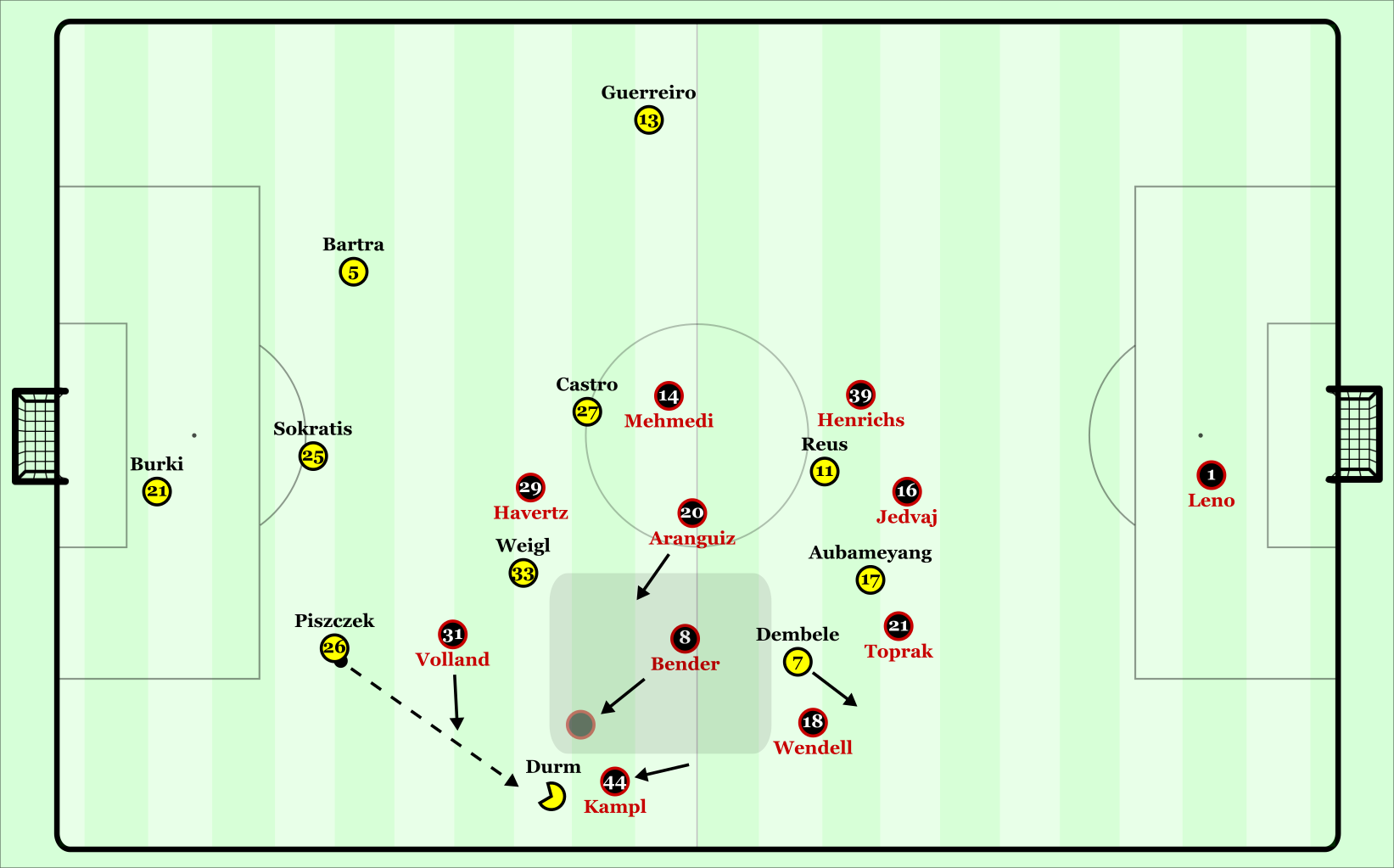

Right-Sided Build-up

When building down the opposite flank, Dembélé would take a much higher position than Castro, occupying the space behind Leverkusen’s midfield. Paired with Durm, the two would take aggressive positions in the structure, threatening to overload spaces behind Bayer’s front four. Closer to home, Weigl maintained a fairly orthodox position, and would try to offer an option to Piszczek by moving out of Volland’s cover shadow.

Their build-up on this flank was less controlled in comparison to that of their play down the left. The visitors had some success in closing down Piszczek, who often struggles against pressure, and due to the advanced positioning of the teammates ahead of him, wasn’t as connected as Bartra on the left. When the Pole received a pass from Sokratis, Kampl used his cover shadow well to cut-off the pass to Durm, which caused hesitancy and allowed Bayer to get closer to their man. If Kampl could attack Piszczek earlier before the player turned, he could expose his bad field of view and force a return ball to Burki.

A benefit to their positioning, though, was that it sometimes forced Bayer’s midfield line into a deeper stance, to minimise the space behind them. As a result, Piszczek could carry the ball further forwards at times before advancing it onto a teammate. Due to the player profiles (and thus the roles and structure determined by them), it was more vertical and chaotic than the left. Guerreiro provided better pressing-resistance, and played slightly deeper than Durm, while Dembélé’s dribbling-focus in the right half-space gave him a far more direct role than Castro.

If they weren’t pinned back, though, Bayer benefited from greater access when pressing this side of Dortmund’s build-up. The team in yellow had less immediate presence diagonally inside from Durm, which allowed Schmidt’s side to press with greater aggressiveness and put him under more pressure. As I mentioned, Durm lacked the pressing resistance of Guerreiro, too, and thus was unable to individually beat his man if required.

While the left side brought about the first goal, the right nearly resulted in the second, but for a poor miss by Aubameyang. Following another left-to-right switch, Piszczek played the ball to Durm, who found Dembélé with a through-ball as his teammate moved behind Toprak.

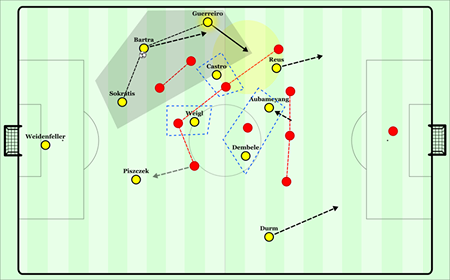

SV-colleague Eduard Schmidt summed up the two tactics nicely in a concise diagram on Twitter.

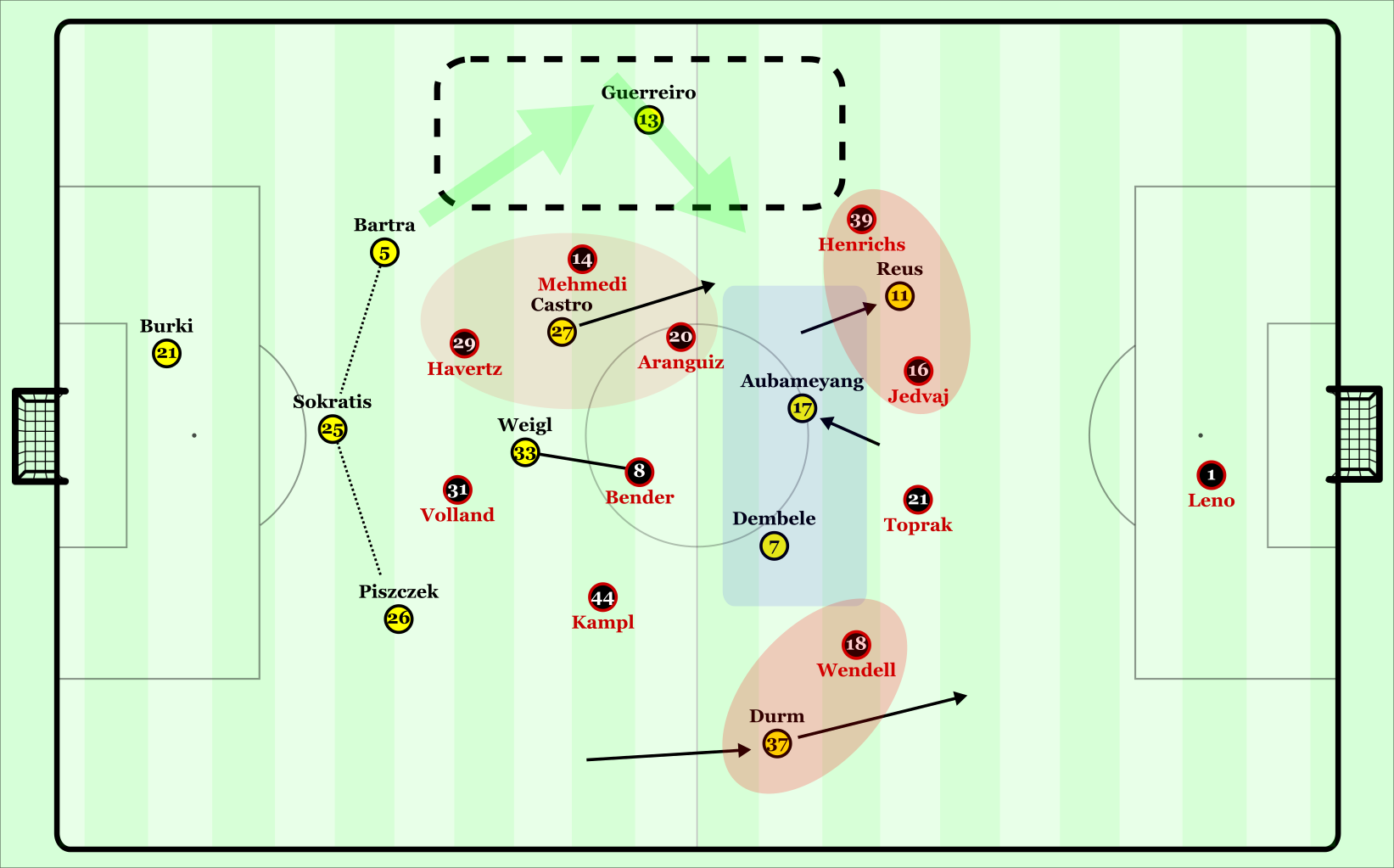

End Product of Build-ups

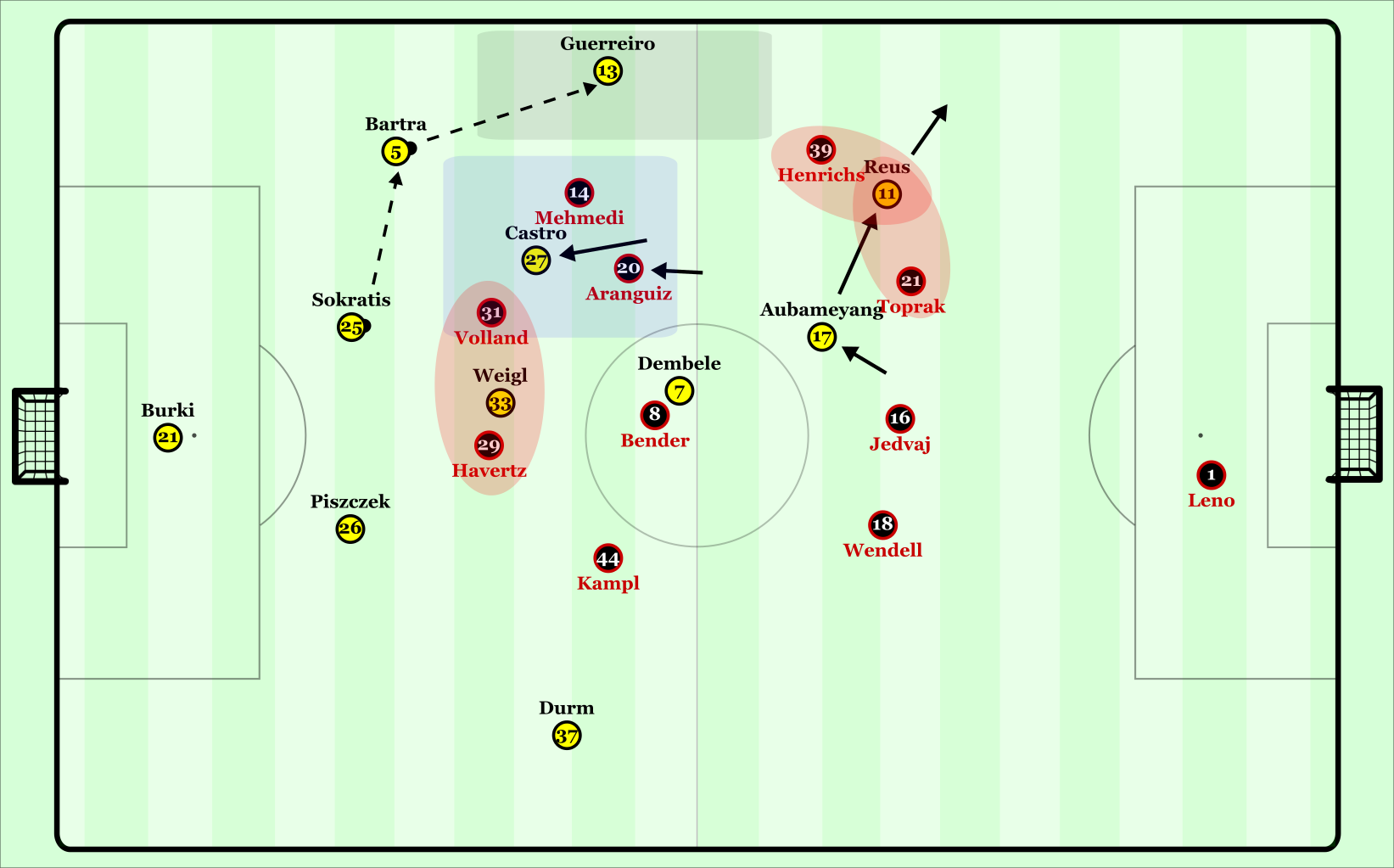

Although the initial dynamics were quite different, one similarity of the build-ups on either side was the end product once Leverkusen’s press had been bypassed. On the left, Reus would often be freed in space behind Henrichs to directly attack Jedvaj, while Dembélé would be put in similar positions (albeit slightly more centrally) on the right.

Both forwards had been on electric form recently, and by putting them into dangerous situations Dortmund were able to threaten well. It enabled the side to attack with great speed once they broke through Leverkusen’s press, and quickly expose the open space before the visitors could recover. On this note – gute besserung Marco!

Durm – Reus Connection

With Aubameyang dropping deeper to increase the presence behind Leverkusen’s midfield line, it was often the responsibility of Reus and Durm to occupy their opponents’ back four. They did so to some effect, through making (or at least threatening to, which would achieve a similar result) frequent runs into depth.

By directing these runs between Henrichs and Jedvaj, Reus could effectively occupy two of the four defenders, and while Durm’s wider positioning made it more difficult to occupy the LB and LCB, he performed his role quite well. Occupying four players with just two forwards can be crucial in helping to create overloads in other areas of the field. With this advantage, Dortmund could use overloads in other areas to break through the 4-2-2-2. They were able to overload Bayer’s two forwards in the first line without losing their presence much in more advanced central positions, while using Guerreiro in his interesting diagonal wide-half-back role on the touchline.

Conclusion

Dortmund continued their brilliant form with a dominant win which ended with Schmidt’s sacking from Bayer. A big part of their performance, was the intelligent ways they devised to break through their opponents pressing, which ultimately aided the rest of their game in possession.

5 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

JD March 6, 2017 um 12:10 pm

Shouldn’t you mention that Dortmund continued with a back four after the 2:1? I thought that Dortmund showed a bad performance during the first 45 minutes of the game. They were never able to build up properly and had huge problems overcoming Leverkusen’s first pressing line. Pretty much all they could do was pass the ball between Bartra, Sokratis, and Piszczek. To get the ball into midfield they were forced to play long balls or high-risk passes that were often intercepted by Leverkusen’s midfield pressing.

The real fun began when Tuchel switched to four defenders and a 4-2-3-1/4-1-4-1 with Guerreiro as a really offensive left-back. They completely dominated Leverkusen after this change, and it felt like it was 2015 again.

tobit March 6, 2017 um 9:45 pm

Sadly I did’t watch the game, but I think those two formations are pretty close to each other with this personel. Durm being the higher Winback or a pretty deep and defensively active winger doesn’t make that much of a difference, especially if the offensive movements stay quite the same (what I suspect from the articles here and at SV.de).

Thanks TP for the coverage of BVB’s buildup down the right. I was wondering how they worked through Leverkusens press without a particularly strong passer or dribbler in sight, but you explained it very well.

Super Dooper Bilbao Trooper March 19, 2017 um 9:48 pm

Yo JD! Glad you commented on this as I wanted to ask your’s and TP’s opinion on how you think people should go about pressing a back 3 with wingbacks. I have a friend who works as a match analyst for an Eerste Divisie side and he said all of their build-up has centred around a back three with deep wingbacks as the opposition find it almost impossible to control. Manchester City had an interesting pattern that you covered in their game against Chelsea but I think (asides from the lack of intensity that you mentioned) they struggled with the deep positioning of Fabregas and Kante because Fernandinho couldn’t screen his defence and be in a position to access Chelsea’s midfield, eventually Fabregas was able to receive and play the ball over the top to Costa, thereafter the lack of endurance from City definitely showed. I was wondering what you thought about Sane pressing the outside centre-back with Kolarov acting as a wingback and marking Moses, thereafter the defenders could slide across and cover long balls into the channel with Stones and Otamendi acting as centre halves and Navas as a right full back. With Sane pressing as part of the front 3 and Kolarov in line with Moses, this would leave Silva free. Now he could either man mark the ball near Chelsea central midfielder or cover in between Aguero (pressing Luiz) and Sane (pressing Azpi) this would allow Fernandinho to screen effectively as Fabregas would be pressed in front, it would also have moved Sane into a forward area and away from the wingback role he was uneasy with. The only problem is that this pressing scheme would leave Hazard and Alonso free on the left wing, but with the increased compactness around the ball Chelsea would have found it much more difficult to get the ball to them. The only other side I have seen control the back 3 moderately well was Manchester United when they focused on pressing the outside centre backs vs Chelsea in the cup. The man orientations they used though opened the centre at times (see Hazard’s turn on halfway against Rojo that led to his dribble and shot in the first half). I’d be interested to hear your opinions, what would you two do?

tobit March 20, 2017 um 5:56 pm

I don’t think there is a universal answer to your question. You won’t be able to cover every single player at all times, so you need to priorize, when and where to attack. These priorities depend heavily on the opponents players (e.g. Sokratis or David Luiz at CB) and your own ones, too (e.g. Pedro or a “lazy” winger).

In general I could think of two options evolving around how to cover the WB:

a) Use a winger to attack the HB and keep the WB in his covershadow to prevent passes out wide. This would be a good idea if you have an intelligent presser like Pedro on both wings. This could easily done from a 433. Depending on your central player you could also set up a pressing-trap for the opponent pivot in the six-space. But this could become very risky when the WB gets the ball from the HB or the DM breaks your pressing.

b) Use two strikers to direct the buildup to the WB and isolate him at the touchline. Less risky in terms of errors, because the WB wouldn’t have as much space to progress and the centre is blocked from the start. This strategy could easily done from 4222 or 3322 formations.

Super Dooper Bilbao Trooper March 20, 2017 um 8:16 pm

Yeah, that’s what I mean, it is so difficult! I think your comments on the player profiles are salient though because along with a good positional structure, that’s what Tuchel intelligently exploited in order to place players with the requisite characteristics in the optimum positions to damage Leverkusen’s structure. Regarding:

a) Yeah you could get pressure on the outside centre back and cover shadow the wingback but you’d either allow a vertical pass (which would then likely be bounced to the wingback free of cover shadow) or allow the ball out the other side if your forward covered the 6. I think because the wingbacks operate on a different line to the back 3 and (in a 4-3-3) the wingers operate on a different line to the forwards it’s crazy difficult to control the initial build-up and shape it one way. I think it requires kamikaze pressing or deeper players advancing from midfield and defense which basically amounts to the same thing.

b) Yes, you are correct in saying that. That’s what United did with Rashford and Mkhitaryan covering the centre and then splitting to press the outside centre back and cover the centre. Then they went man to man in the area around the press. This worked better because it was kind of like a mid-press and they didn’t expose themselves with needless running, though at times the centre was opened because of the man-oriented way they defended.

I think Schmidt’s problem though was that (aside from Tuchel’s outstanding preparation) he didn’t anticipate the initial structure being played round, Leverkusen pressed very well under him but they didn’t seem to adapt either in game or from game-to-game very much. I wonder how this bodes for the rest of his career?