Franz Beckenbauer: The Kaiser

The Kaiser of German Football roamed and glided over the football pitches of the world for nearly two decades. There were arguably six defining games of his career. I give you, Franz Beckenbauer, the deep-lying commander who defined a generation.

***

He is a gem

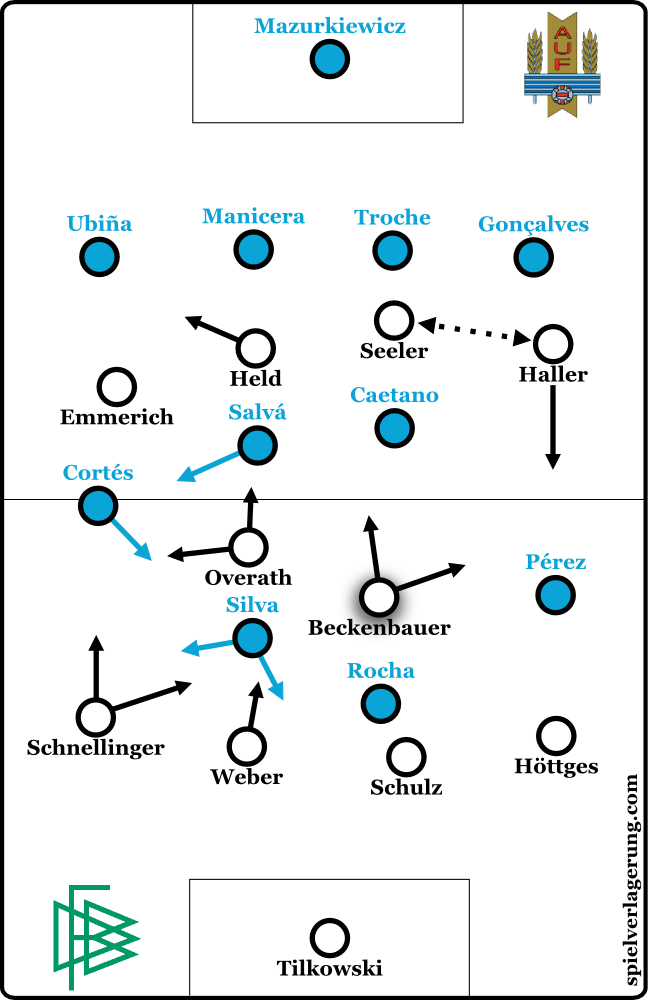

Hillsborough, Sheffield, Saturday 23rd July 1966. World Cup Quarter-Final. West Germany 3-0 Uruguay.

West Germany were the favourites against Uruguay. Both teams played in the most popular formation of the day, 4-2-4. Cologne workhorse Wolfgang Overath played beside the man capable of everything from Munich, in the heart of the German team. At 20 years old Beckenbauer is already authoritarian. Teammates respect him. Opponents fear him.

Beckenbauer is no prima donna and fully served the team. He balanced the team when defender Wolfgang Weber pushed forward from the back, reacted when Overath played wide and when left-back Karl-Heinz Schnellinger played narrower. In the last line of defence, he also deputised in the system of two-man marking.

Beckenbauer is no prima donna and fully served the team. He balanced the team when defender Wolfgang Weber pushed forward from the back, reacted when Overath played wide and when left-back Karl-Heinz Schnellinger played narrower. In the last line of defence, he also deputised in the system of two-man marking.

Those fans of a German persuasion were looking at a young, gangly footballer. In aerial duels he was overpowered as the Uruguayans bombarded the German 18-yard box with cross after cross and Beckenbauer looked lost.

It was a completely different ball game when the the ball was on the floor. Beckenbauer’s element. He took the game by the scruff of the neck, initiated passing combinations in midfield, his teammates reacting to one-two passes at high speed. He travelled even faster with the ball at his feet. The Uruguayan defenders with their pure physicality do not have an answer to the threat he posed.

Beckenbauer was always the first to support the striker. Time and again he drifted wide to the wings. In attack he was a whirling dervish, shoving opposing players out of his way with his feet.

Without the ball he gave a sense of calm, considered and elegant. Employing lateral runs to protect those of his teammates running ahead of the ball he destabilised the playing style of the South Americans. He did not engage in one-on-one tackles. He pressurised with his mere presence.

Time after time Beckenbauer and Overath left the middle channel open, pre-occupied with the passes out wide. Uruguay fell into the trap, lured into playing through the midfield and limited to shots from distance. This is Beckenbauer’s take on footballing psychological warfare.

Despite taking an early lead a true battle ensues. The Uruguayans trip, gesticulated and played dirty. Beckenbauer was the first to forge a way through the maze, stepping higher up the pitch, receiving the ball behind the Uruguayan defence, rounding goalkeeper Ladislao Marzurkiewicz with poise.

***

He roams free

Städtisches Stadion, Nuremberg, Wednesday 31st May 1967. European Cup Winner’s Cup Final. Bayern Munich 1-0 Glasgow Rangers.

A young Beckenbauer played alongside Werner Olk in central defence. Who is responsible for what defensive job, is clearly defined. Olk, an East Prussian native, played sweeper and covered the opposition striker. He fulfilled the duties of a run of the mill defensive unit.

Beckenbauer belied his tender age of 21 and was already a gliding authoritarian in the back four. He positioned himself mostly to Olk’s left-hand side, becoming a playmaker when in possession. To a certain degree Manager Zlatko Cajkovkski gave him a free rein.

Beckenbauer exuded an air of assuredness. In contrast his three colleagues were overly aggressive. They were anxious to close down Rangers’ strikers at the earliest opportunity. Beckenbauer plugged gaps as and when they appeared. He pressurised simply by occupying space. Few opposition players had the courage to go toe-to-toe with him in the tackle. He pressed without the ball, snuffed out attacks as if by magic.

True to Albert Camus’ assessment that ‘First and foremost freedom is not out of privilege, but out of duty’ Beckenbauer worked to Cajkovkski’s instructions. As a number five, the traditional roaming man or Libero, he was also limited in as much as he had to be a link in the defensive chain.

His creative abilities shone through when going forward. Unflustered by attempts to dispossess him he wanted to increase the tempo. The highlights of his performance were mazy runs deep into Glasgow Rangers’ half, involving his teammates, giving them the opportunity to shine as pin-point, considerate passes reached eventual goalscorer Franz Roth and co.

Beckenbauer stroked the ball with reverence. He paid respect to the spherical object integral to the game. The opposition forfeited possession at will. To give up possession of the ball with such disregard went against Beckenbauer’s belief of how the game should be played, it was an affront to him.

The crowd turned up the volume as he took possession of the ball on the edge of the opposition’s box and in no time at all, and from a standing start, broke away thirty yards down the wing.

Beckenbauer did not just have a glowing aura, his bolt-upright stance, the eagle-eyed view of a large proportion of the play enabled him to weigh up a number of moves. He identified open space and noticed vulnerabilities. Switch passes altered the mode of attack carried even more threat. But he also recognised when dribbling was not required, stopping to play the safe option. With great power comes great responsibility.

***

He dominates

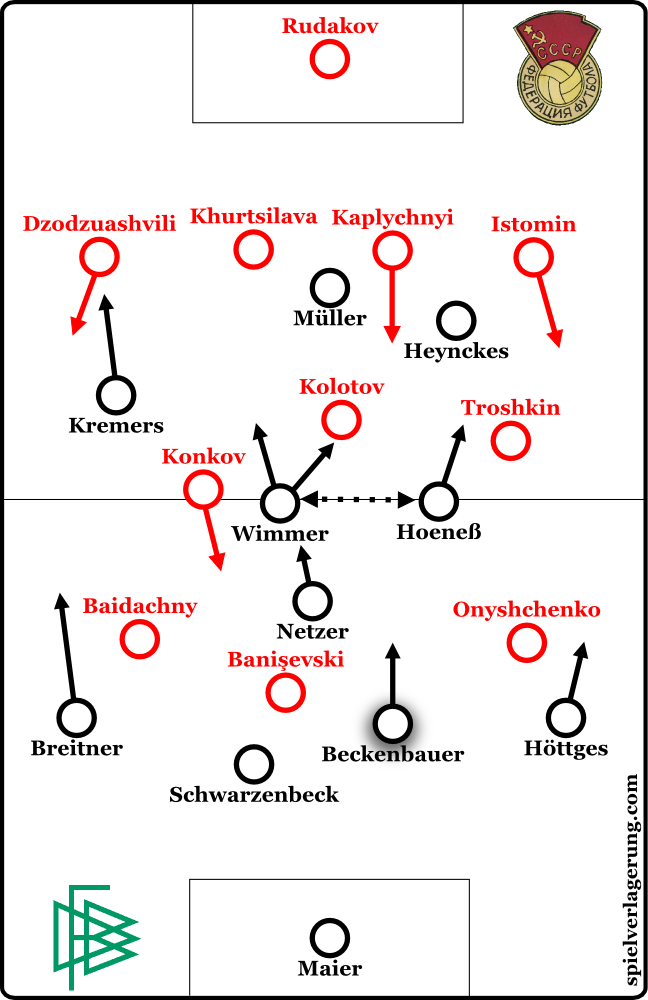

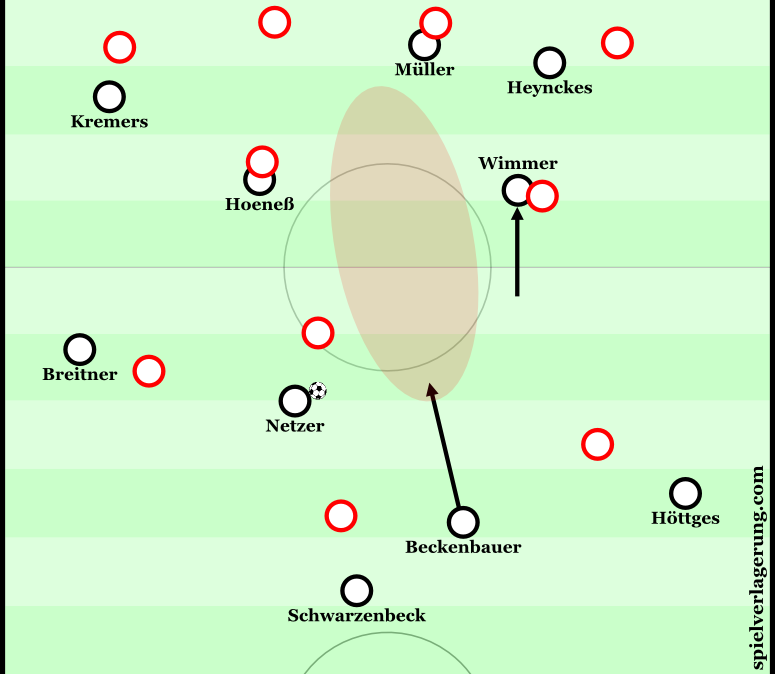

Heysel Stadium, Brussels, Sunday 18th June 1972. European Championship Final. West Germany 3-0 USSR.

The USSR met West Germany. A few weeks after the leading power of the Eastern Bloc had had to deal with a 4-1 debacle of a defeat in the opening game at the new Olympic Stadium in Munich, the Henry Delaunay Trophy was at stake. West Germany Manager Helmut Schoen entrusted the job to the same 11 who had defeated hosts Belgium (2-1) in the Semi Final.

The Final developed into an exhibition of West Germany’s power. It would even be recalled as the highpoint in the history of the National Team. The predominantly Ukrainian opponents did not even get a sniff of a chance.

The Final developed into an exhibition of West Germany’s power. It would even be recalled as the highpoint in the history of the National Team. The predominantly Ukrainian opponents did not even get a sniff of a chance.

In between time Beckenbauer had been given his trademark “Kaiser” nickname. In the final he was played with fellow Munich native Georg Schwarzenbeck in the middle of the back four. Schwarzenbeck, “The Kaiser’s Cleaner” could not have been more different to Beckenbauer. He was the antithesis in human form, they were ying and yang.

Beckenbauer was able to sit back, to pounce on second balls. He anticipated ricochets and intervened in midfield at the right times. The ball was drawn to him but he was also capable of being relaxed and stepping aside. He allowed the egocentric Netzer to take over the responsibility of build-up play, only now and again involving himself to play flat, short range driven passes that land on the instep of his teammates.

Right-back Horst-Dieter Hoettges had the most to gain from Beckenbauer playing this way. When Beckenbauer was pressed, he did not run blindly forward. He delayed the inevitable and gave Beckenbauer an option out wide. Or Hoettges limited his runs, taking the pace out of the game, subsequently able to serve the sprinting runs in behind of ‘Marathon Man’ Herbert Wimmer, scorer of the second goal, perfectly.

Beckenbauer’s occasional misreading of his surroundings was the only dampener on proceedings, causing the USSR to carry an attacking threat when he did not dribble at pace.

Beckenbauer made himself available to support attacking forays. Against the deep-lying USSR defence he offered Wimmer and Uli Hoeness an equally deep-lying passing option. When no forward pass was on for either of the West German midfielders, they passed to Beckenbauer. He relieved the pressure on his midfielders.

This kind of support was not reciprocated when he ventured forward and his passing angles were slightly off. He had to wait, becoming impatient. Only late on did he let a striker get a run on him, no Soviet players really trusted their ability enough to target The Kaiser. Beckenbauer was surrounded in a protective bubble.

In the end, Netzer had to accept a role behind Beckenbauer and allowed the true Maestro more time on the ball, becoming a second player in the middle of the park who ran at defences. Recognising the impending danger the USSR played narrower but Beckenbauer played the ball wider in response, preferring to go around and not through the Soviets.

In the end, Netzer had to accept a role behind Beckenbauer and allowed the true Maestro more time on the ball, becoming a second player in the middle of the park who ran at defences. Recognising the impending danger the USSR played narrower but Beckenbauer played the ball wider in response, preferring to go around and not through the Soviets.

In the lead up to the opening goal, Netzer opened the gap for Beckenbauer, dribbling with poise to the edge of the box before assisting the goal with a short and precise pass.

Beckenbauer showed precision and a canny ability to read the game, and elegance as well as awareness for movement. He stroked the ball with the sole of his boot and in one seamless movement chipped it to his nearest teammate.

All the while the clock ticked on. As it did Beckenbauer changed his tact. Suddenly he became the reassuring leader at the back, clearing balls, gesticulating and swearing at his teammates lack of focus. He positioned himself behind his right-back, covering him in the case of attack. When the USSR attacked out wide he carried the ball to the opposite end of the field himself.

Later in proceedings fans saw him in the attacking half only. He slid behind the Soviet attackers and pressurised their defenders in the way he played and also psychologically. Nobody would have dared to criticise his lack of defensive work. In these instances his dominance ensured his immunity. Alas, he had Schwarzenbeck as adept cover.

***

He is no sweeper

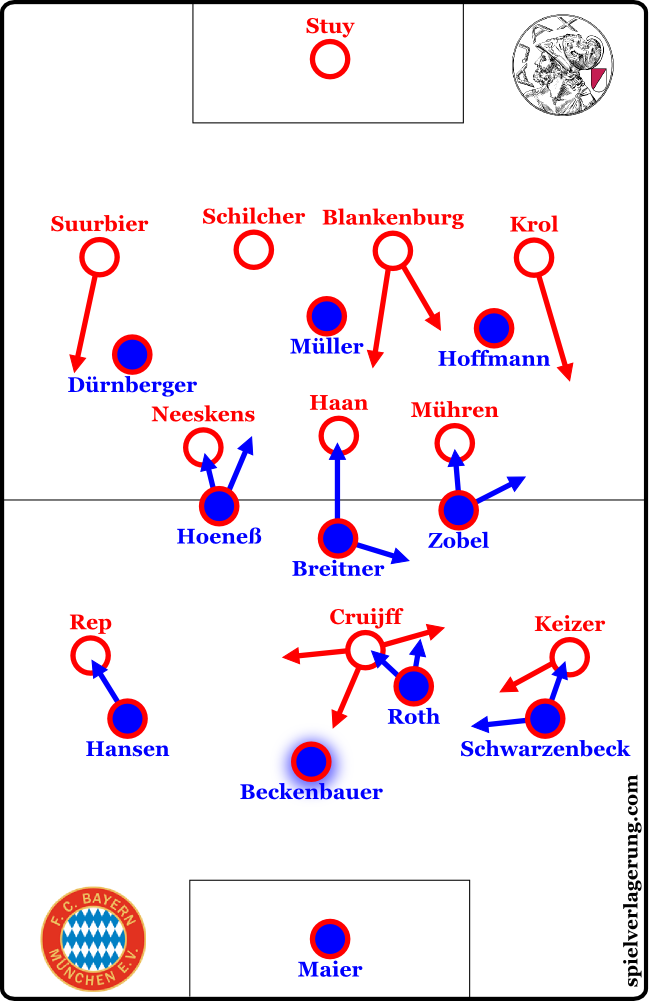

Olympisch Stadion, Amsterdam, Wednesday 7th March 1973. European Champions Clubs Cup, Quarter Final, First Leg. Ajax Amsterdam 4-0 Bayern Munich.

When faced by far and away the best team in Europe at the time, Ajax Amsterdam, Bayern Munich would be truly tested. The reigning German Champions were rank outsiders. Manager Udo Lattek chose to deploy the simplest of all defensive systems. Everyone apart from Beckenbauer was assigned a specific Ajax player to man mark, even during breaks for a quick cigarette.

Roth “The Bull” had to handle Johan Cruyff. Many of their one-on-one tussles were in midfield. Schwarzenbeck was to stay on the heels of Peter Keizer.

Beckenbauer played a lone sweeper behind the back four, but did not pass the ball without looking up. As the Dutch began to press him he answered back with measured runs with the ball at his feet.

Beckenbauer played a lone sweeper behind the back four, but did not pass the ball without looking up. As the Dutch began to press him he answered back with measured runs with the ball at his feet.

But The Kaiser was given no room to be negligent as many of his switch passes were intercepted by Ajax’s pressing machine. He got stuck in, was rash, but followed Lattek’s instructions. First and foremost, he was a distributor of the ball. Forays forward were fraught with risk, so Schwarzenbeck grew into his role as “Kaiser’s Cleaner”.

But Beckenbauer did take his chances when they came, casting himself as the playmaking opportunist. Ajax were unable to press relentlessly, needing breathers from time to time, when Bayern’s Maestro would initiate moves forward with passes into midfield. The first touch of his teammates had to be crisp, the passing precise, otherwise they would be outnumbered by a pressing Ajax. On other occasions Beckenbauer ran with the ball, the archetypal sweeper in open space.

He was a calculated gambler, judging exactly when Ajax had limited themselves and were susceptible to attack. Then he would edge forward, leaving Rep and Kiezer on their respective wings. Sometimes he was overcome with some sort of tentative courage, other times he would fall into his old patterns, on one particular occasion taking a throw-in near his own corner flag with no one in support and marked by two men, displaying absolute belief in his abilities.

Lattek believed the European Champions were not infallible when faced with man-on-man marking, and he demoted his Kaiser to quartermaster. Beckenbauer stayed behind the lines when the Dutch attacked, rarely exerting pressure by occupying space. He barely knew which position to take up.

Until they were broken down by a united front in the second half, Bayern survived unharmed. As it transpired, Beckenbauer was not up to the aerial challenge on this occasion. He was only able to defend so many high crosses and balls into the box from corners. Ajax recognised shortcomings in The Kaiser’s all-round game. He is no sweeper.

***

He is a striker

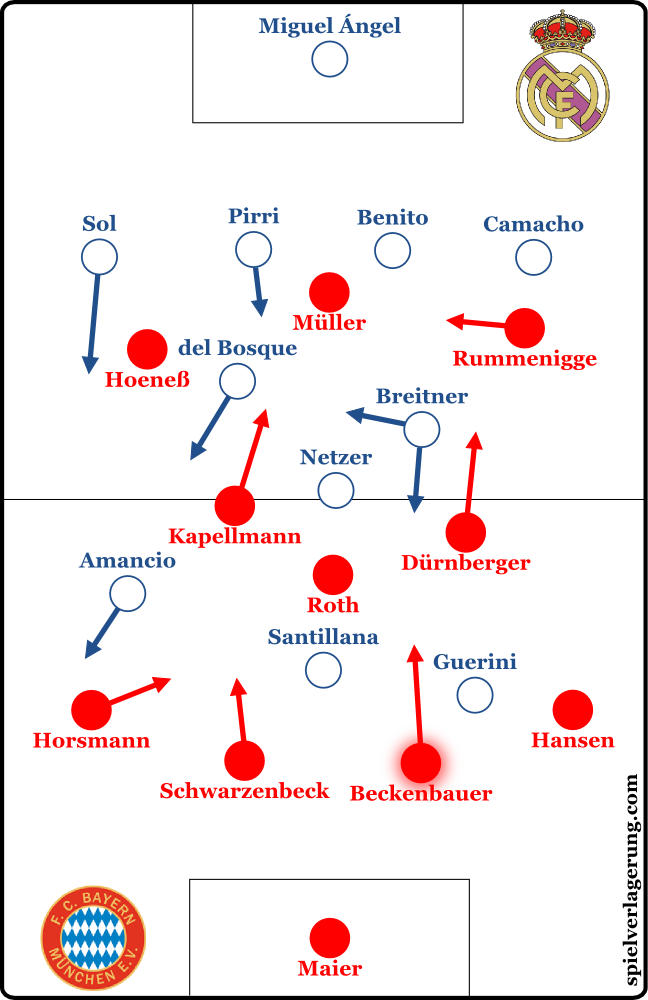

Olympiastadion, Munich, Germany, Wednesday 14th April 1976. European Champions Clubs Cup, Semi Final, Second Leg. Bayern Munich 2-0 Real Madrid.

Bayern Munich found themselves on their way to a third European Cup Final in a row after the first leg of the Semi Final versus Spanish powerhouse Real Madrid ending all square 1-1. The German’s wanted to cement their place in the pantheon of greats in the continent’s foremost club competition, and would book their place with a 3-1 aggregate victory.

There were some familiar faces in Real’s ranks: Gunter Netzer and Paul Breitner, with whom he had had many tussles during his time. Although The Kaiser was given as a centre-back on Manager Dettmar Cramer’s team sheet, in reality his role developed into something else entirely.

There were some familiar faces in Real’s ranks: Gunter Netzer and Paul Breitner, with whom he had had many tussles during his time. Although The Kaiser was given as a centre-back on Manager Dettmar Cramer’s team sheet, in reality his role developed into something else entirely.

In the beginning he lent a hand to his fellow centre-back Schwarzenbeck who was untypically brash. A few passes landed on “The Cleaner’s” instep, but it was the calm before the storm. From then on Real Madrid were swept aside.

Los Blancos left Beckenbauer unmarked in between the lines. Not every pass is on the mark but the pressure is mounting with every passing second. In the lead up to Gerd Mueller’s opening goal he materialised in the opposition half and set Bernd Duernberger on his way. It was the beginning of the end for The Madridistas.

Shortly afterwards Beckenbauer found himself once again at Madrid’s 18-yard box and is suddenly surrounded by four defenders, half of whom are past teammates Netzer and Breitner on the left hand side. He shook them off easily, they stood off him; revering The Kaiser, forming a welcoming committee.

In midfield, Beckenbauer had many options, the Spaniards literally giving him an array of passing choices. He gifted the onlooking fans titbits of exquisite football, swept precise and considered switch balls to the wings that fell like raindrops onto the feet of his teammates. Beckenbauer did not just play the first pass, he used his Bayern teammates to build the next attack.

Beckenbauer played a supporting role to his fellow defenders, occupied space behind Real’s first line of defence and simultaneously offered himself up to Schwarzenbeck and Co. as someone to play through with no apparent danger. As the Spaniards plucked up the courage to toil away in the face of inevitable defeat, Beckenbauer held himself personally responsible to intercept every pass to be both a striker and defender. All in a day’s work for the Boss.

***

He is a gentleman

Tampa Stadium, Tampa Bay, Florida, Friday 29th May 1977. North American Soccer League (Franz Beckenbauer’s Cosmos Debut). Tampa Bay Rowdies 4-2 New York Cosmos.

Football became the new sporting trend in North America. Pageantry on a record scale sets the stage for old European legionaries. Beckenbauer decided to leave the media spotlight of Germany, opting for New York as his new home in the 10th season of the North American Soccer League. Playing alongside Pele should be a footballing extravaganza.

50,000 fans packed into Tampa Stadium eagerly anticipate the New York Cosmos’ entrance. Beckenbauer was well aware that he played on another level but nevertheless his teammates ineptitude left him brooding as the Cosmos are taken apart piece by piece. Without protection in the space usually occupied by the Number 6, The Kaiser had to ward off attack after attack, but he could not stop everything.

Beckenbauer gesticulated and gave out instructions, not a hint of disobedience as he led and reverts into his old sweeper role.

In the beginning he showed no signs of aggression. The opposition striker tried to drive him wide. As the blue touch paper was lit, Beckenbauer began to distribute low driven passes. He is alert and intercepts passes, the Rowdies chose instead to attack via the flanks and man mark Beckenbauer.

Beckenbauer played the ball earlier out from the back and searched time and again for Pele with raking balls to the edge of the box. When the Brazilian star man went to work in the attacking half, Beckenbauer stayed back, preferring targeted dribbling to create space, enchanting the fans with fleet footed movements to the left and spraying first time balls to the right.

Now and again flashes of the old marauding Kaiser appeared, no-one daring to take him on. He patrols the pitch with authority and plays initial passes with assuredness. However, he ends up on the losing side. Beckenbauer absorbs the blow of disappointment unruffled. He would have the last laugh as Cosmos would go on to secure their second NASL title with a 2-1 win over Seattle Sounders in the 1977 Soccer Bowl.

***

Conclusion

Beckenbauer was both a relict to be marvelled at and a prototype, embodying the smooth and contemplative defensive midfielder. He tackled rarely and only then when the timing was right, not just because of the penetrative power robust tackling provided. Beckenbauer’s runs meant danger at all times, although he is a child of his time. Alone he mechanically and almost nonchalantly controlled proceedings. Between all the genius there was tedium. Laser precise raking balls became the norm, stupefying the onlooker.

Beckenbauer was a leader who could work as part of the group, but he was no run of the mill worker who aspired to lead. Above all his Aura and how he carried himself, he was an extraordinary act on the world footballing stage. Nobody handed his aura to him, he provided balance to the national team with his body language, open and confident. He was a spectacular player, an underrated athlete and a special technical talent with a talented tactical mind, always viewing every blade of grass.

He never looks down. A Kaiser never looks down.

Translated by Alasdair TL Park (@parky243) from the German Original by Constantin Eckner.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen