Antonio Conte’s tactical masterclass

When there are winners, there have to be losers. Antonio Conte and his Italy team outsmarted Spain in one of the best matches of the Euro tournament. While Italy will play Germany in the quarterfinals, a generation of Spanish players is now one step closer to riding into the sunset.

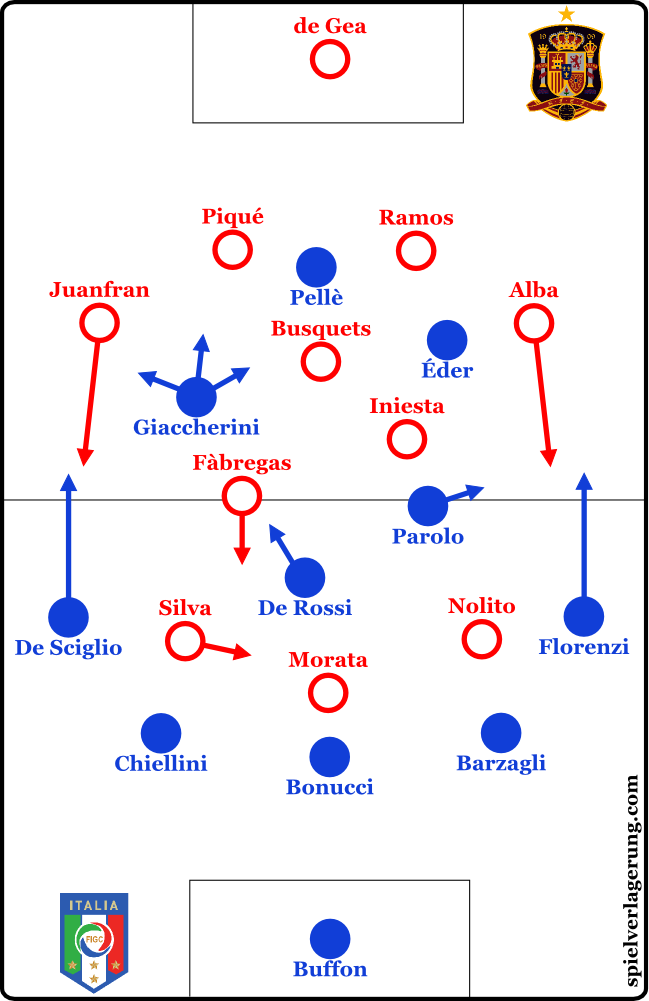

Line-ups

Line-ups

After a final group match full of changes, Antonio Conte fielded his preferred starting XI with the well-known Juventus back three including Andrea Barzagli, Leonardo Bonucci and Giorgio Chiellini. Daniele De Rossi again played in the holding role, while Marco Parolo and Emanuele Giaccherini were the box-to-box runners in midfield, although the latter often made the extra man up front on the left. Conte, moreover, decided to play Alessandro Florenzi and Mattia De Sciglio on the wings, because Antonio Candreva was out injured.

Meanwhile, it seemed that Vicente del Bosque didn’t even think about changing his starting line-up, as Spain played with the same one for the fourth time in a row. That meant that two Spanish players who will be managed by Conte at Chelsea next season, César Azpilicueta and Pedro, didn’t make the first eleven.

Instead, it was business as usual. Jordi Alba and Juanfran bombed up and down the flanks. Andrés Iniesta and Cesc Fàbregas roamed through the half-spaces, with Sergio Busquets covering them as well as being pivotal to the Spanish build-up play. Up front, Álvaro Morata once again was the target player, flanked by Nolito and David Silva, with the latter being a somewhat additional midfielder in Del Bosque’s system.

Man-marking everywhere

From minute one, Italy clearly showed their willingness to act more intensively in defence than they did in their group stage matches. One of the first scenes showed the Squadra Azzurra pressing Spain’s build-up players heavily. Conte’s side applied a rigid man-marking scheme, with either Graziano Pellè or Giaccherini marking Busquets.

Although Giaccherini was a centre-midfielder on paper, he played a left winger/left number eight hybrid role for the most part. But thanks to his stamina and durability it looked like he almost had two roles he could fill at the same time, as he often travelled between the first and the second line. However, due to the man-marking scheme he was usually attached to Gerard Piqué, while Éder marked Sergio Ramos on the other side. In the meantime, De Rossi showed tremendous courage as he left his position fairly often in order to follow Fàbregas who dropped deep in the right half-space, when Spain were building up.

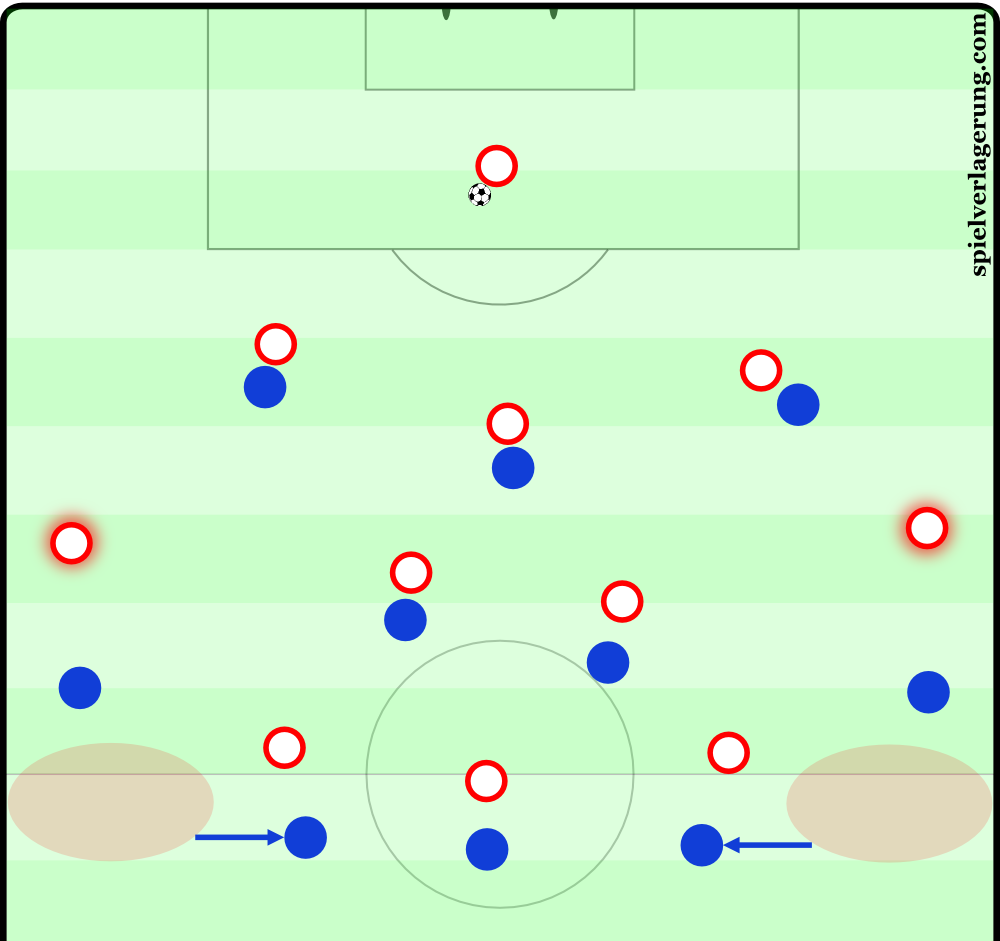

In those situations, both Italian wing-backs were asked to move a few yards forward and pressure the opposing full-backs in the early phase. Yet, they had to drop back afterwards to cover the outer zones next to Italy’s initial back three. Both Silva and Nolito moved inwards, which forced Chiellini and Barzagli to follow, which then led to De Sciglio and Florenzi moving backwards. The phase in which Italy’s wing-backs had to go back and protect said zonesvaried, but usually Spain’s full-back had the chance to receive near the touchline freely.

Unfortunately for La Furia Roja, on occasions where both full-backs had the space to get the ball early on, without being pressured, David de Gea often knocked the ball down the middle. Spain’s goalkeeper reacted to the fact that Italy tightly marked his first three passing options, surprisingly badly. If Italy apply a similar strategy against Germany, Manuel Neuer will frequently have the opportunity to get the full-backs involved.

That said, Italy weren’t one dimensional in their defensive approach. As an alternative to the more intense man-orientated version, they also used a more compactness-focused pressing when both Ramos and Piqué remained unmarked, because Giaccherini and Éder stood deeper to close down the central passing lanes.

The Azzurri avoid Busquets

Italy’s success when pressing Spain wasn’t the only story of this match, though. Conte’s team saw much more of the ball than expected. They not only tried to avoid conceding a goal, but also intended to create chances from established possession. At the end of the first half, WhoScored’s live stats showed Italy having over 51 percent ball possession. Only a few goal-scoring opportunities came from counter-attacks while, at the same time, the Squadra Azzurra displayed an effective concept when building up.

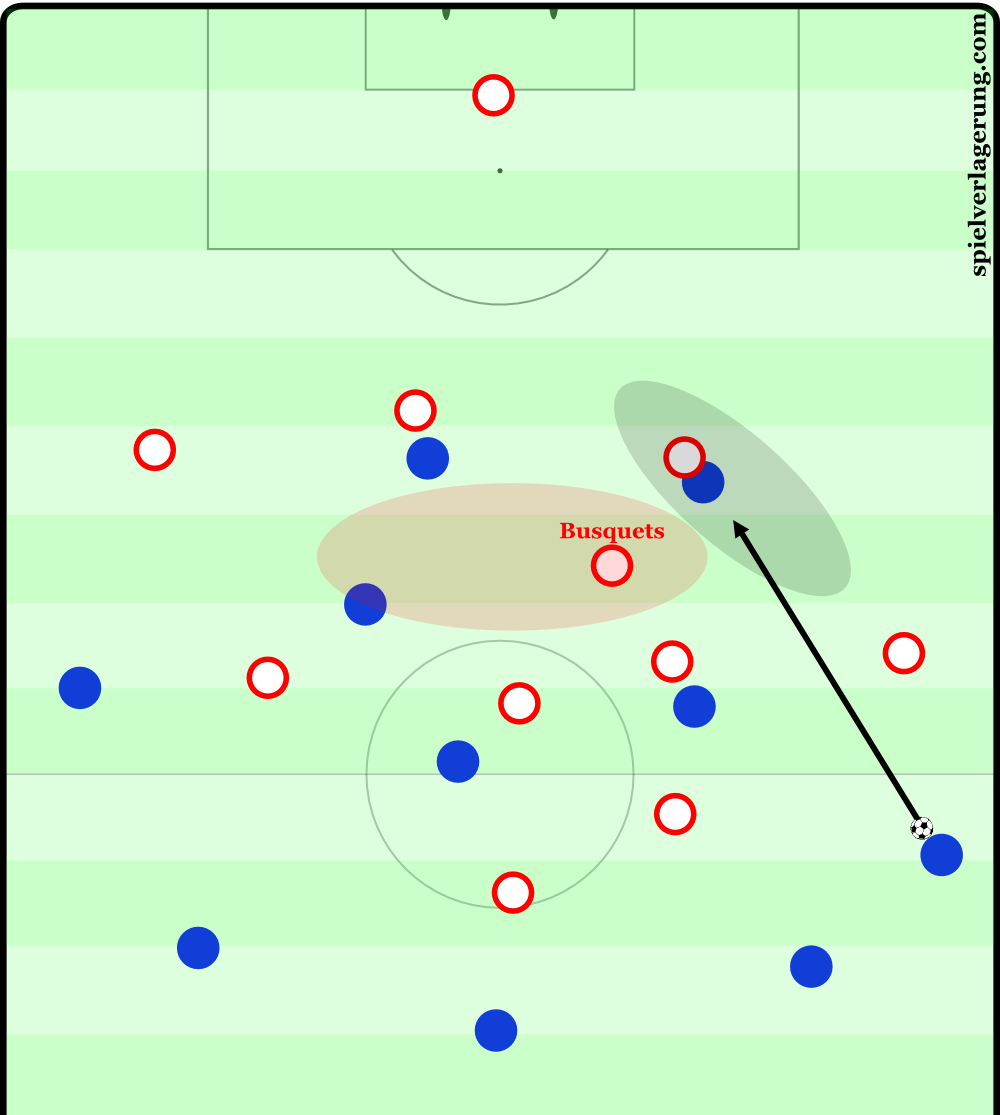

In addition, Spain’s defensive structure helped Italy moving the ball forward. For instance, both Spanish centre-backs intended to man-mark their respective opponents. When Italy played the ball to one of their wing-backs, usually the next step was to attempt a deep pass towards either Pellè or Éder. One could assume that those diagonal balls should go right through the Busquets zone which is normally a dead end for every attack.

However, as Busquets had to leave room for the centre-backs to advance in order to continue the man-to-man coverage, even though the opposing strikers dropped back, Spain’s number six couldn’t intercept said passes as often as it would have been possible if Del Bosque had adjusted the structure. After receiving a long pass, both Pellè and Éder mostly left the centre – and therefore escaped Busquets’ clutch – by either directing the ball back to a wing-back or quickly turning towards the outside lane and trying to slide around the man-marker.

Italy punish sloppiness

After around 20 minutes, Spain became more and more nervous, because they couldn’t establish their dominance as they prefer to do in all of their matches. As a consequence, Del Bosque threw at least eight players towards the opposing box to pressure Italy and counter-press them as quickly as possible. However, Spain’s counter-pressing didn’t work, and with only the centre-backs and Busquets behind the ball to protect the backfield, they gifted Italy the opportunity to hit them on the break, in addition to Italy’s already dangerous possession game.

Spain got under even more pressure, when the favourites went behind. Italy’s go-ahead goal was ultimately scored by Chiellini after a free kick by Éder followed by De Gea’s unsuccessful effort to clear the ball off the danger zone. Yet, in fact, it was Spain’s desultory zone coverage that caused this goal. Bonucci and his team-mates at the back were able to cut through the opposing formation with their passes several times.

Iniesta and Fàbregas did cover the half-spaces, keeping an eye on the advancing wing-backs, but the middle was open. Even Busquets couldn’t intercept every pass. Pellè and Éder moved slightly laterally up front to find room where they were able to receive long passes. Spain’s man-marking centre-backs remained behind both centre-forwards, with the intention to stop their respective opponents after the ball reached their feet. Unfortunately for Spain, this particular strategy can always lead to fouls in the own third. And in the 33rd minute of this match, Ramos committed such a foul on Pellè, which led to Éder’s free kick.

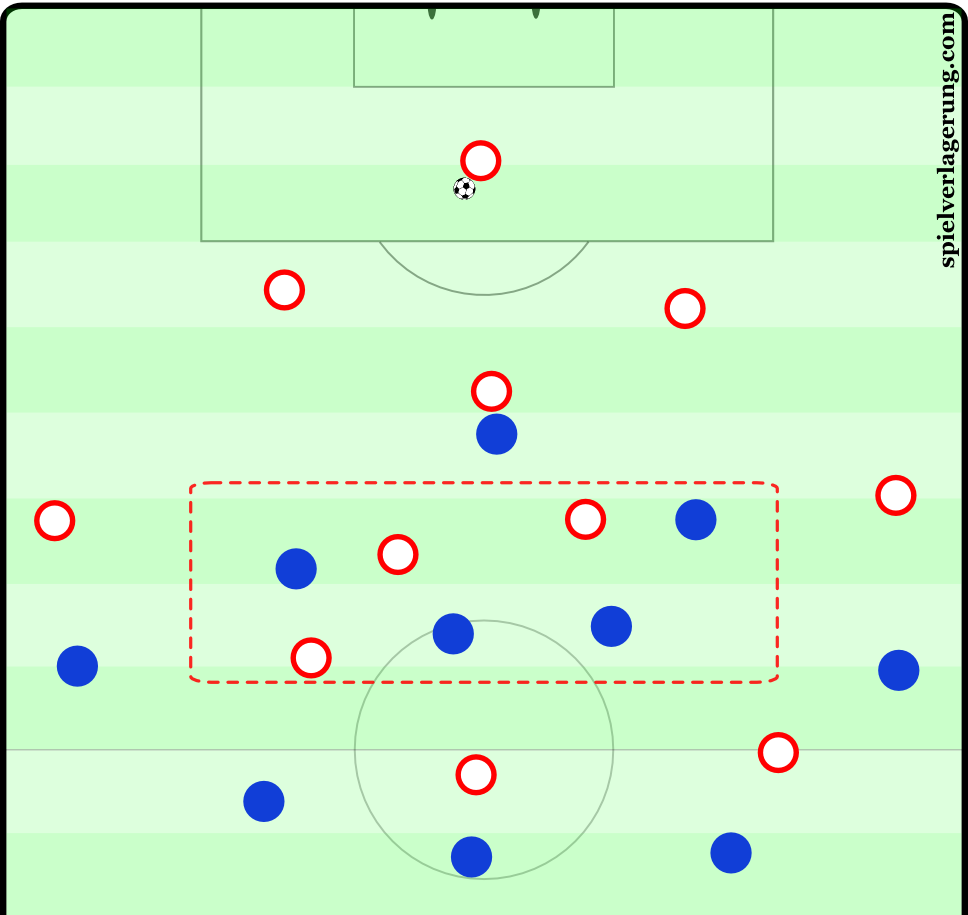

Afterwards, Del Bosque’s team were finally able to take the command, with 61 percent ball possession until the interval. That said, the coordination between the attacking players seemed to be uncharacteristically bad for a Spanish team. La Furia Roja often attacked through the left-half-space, involving Iniesta as the main ball-carrier.

Meanwhile, Silva and Fàbregas waited in the other half-space, standing next to each other and right in the cover shadows of Giaccherini and De Rossi. They were dead players in those situations and forced Iniesta to play longer cross-field passes towards Juanfran, which helped Italy to regain a compact defensive formation before Spain’s right-back could even start dribbling towards the goal line.

Second half

During the half-time break, Del Bosque decided to substitute Nolito, who at times looked like a madman, but was completely ineffective in his inverted winger role. In what was probably Del Bosque’s last match in charge of the national team, he thought it was the right time to adopt a “bombing into the box” strategy, as he brought on Aritz Aduriz.

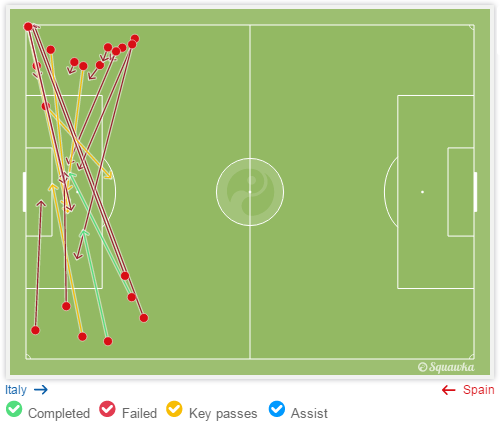

Spain’s crosses in the second half | Squawka.com

The Bilbao forward supported Morata in the penalty area, when Alba and Juanfran were running down the flanks and crossing the ball into the middle. Therefore, Spain gave up their strategy of breaking the opponent down with a precise passing game and intelligent spacing. Of course, they continued to move the ball through the centre in the first phase, but then quickly turned their attention to both full-backs who were supposed to deliver the assists.

It didn’t work out. Here and there, Spain came close to scoring, but against Italy, with their physically imposing centre-backs and the kind of old-school defending that involved all the little (dirty) tricks to keep the opponents off the danger zone, it might have been the wrong decision to go into that sort of battle.

Later, Del Bosque replaced Morata with right-winger Lucas Vázquez in order to return to the attacking strategy he applied in the first half, although Vázquez acted like an outside forward, while Silva roamed through the middle. Spain changed their focus from crossing to overloading the space in front of the box. It became even more apparent, when Del Bosque had to substitute Aduriz who injured his head early into the second half and replaced him with Pedro who served as a number nine until the final whistle. Granted, Pedro was the only forward left on the bench.

Until the hour mark, Italy still stuck to their plan of closing down Spain’s centre-backs early. Even in the 60th minute, Giaccherini, Éder and Pellè charged forward to mark their respective opponents, forcing De Gea kicking the ball forward multiple times.

And, on the other side, Conte’s team were still dangerous after gaining ball possession. Especially Éder’s clear-cut chance after 55 minutes showed how effective their attacking game was. In that particular situation, Thiago Motta, who had come on to replace De Rossi the minute before, started the play by passing the ball towards the right side. After that, Parolo found Pellè with a vertical ball. Ramos again marked Italy’s centre-forward closely, but wasn’t able to intercept the pass, which led to Pellè sliding the ball into Éder’s path. It was a great one-contact-play, but also the last Italian shot attempt until the closing phase of the match.

Spain had still a half-hour to even the score. However, they couldn’t get past Gianluigi Buffon, despite having a few promising chances. At the end, Pellè closed the show, though. After a counter-attack that Spain didn’t defend intensively, Lorenzo Insigne drilled a great cross-field pass to Matteo Darmian on the right. He moved into the area and stabbed a low cross that was deflected up to Pelle, who volleyed it in from a few yards.

Conclusion

Normally, the general public would blame a lack of penetration when Spain lost a match, but that time it was the fact La Furia Roja couldn’t establish an effective possession game in the first half that turned the match into an open fight. Often enough, it looked like Italy had 14 players on the pitch, because several Italians advanced and chased back so quickly, while Spain was struggling to press in packs. Instead, the defending champions couldn’t handle the amount of overloads Italy created even within a single play.

The Squadra usually intended to make the pitch very big in attack, with both wing-backs pushing extremely high and wide, while Giaccherini and Parolo moving towards the touchlines. Conte sought to open the centre, so Pellè and Éder could pick their spots, while avoiding Busquets who not only struggled with the movement of his own team-mates, but also with size of the zones he had to cover. At one point, even he can’t fill all the holes anymore.

Four years ago, Spain picked Italy apart in the Euro final in Kiev. On Monday, Conte turned the tables and scored a deserved win.

11 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

4IN July 3, 2016 um 12:02 am

Thanks for beautiful column. What does ‘Squadra’ means?

CE July 3, 2016 um 7:30 am

Team. Similar to “Seleção”, “Mannschaft” etc.

Rabony July 5, 2016 um 6:00 pm

And I always thought, the German XI was “die Elf” 😉

CE July 5, 2016 um 7:15 pm

That’s another version.

Jackson Price July 1, 2016 um 11:08 am

What application do you writers use to create the exhibits of the tactical formations? I’m hoping to start developing my own tactical analysis and haven’t found a good application to create graphics of the team formations. Let me know what you find useful, thanks.

Sudha June 30, 2016 um 12:06 pm

Let me start by saying that I agree with the opinions above the Italian’s tactics were spot-on and the players worked themselves to the ground.

However I think one of the unique features of the Italian game also contributed the fact that Italy able to beat those teams who are stronger on the paper like Spain and Germany. This is because of the nature of the Italian game and players. They are incredibly flexible – that they can tackle, cover spaces, tactically well schooled, highly fit and able to attack too. Most teams’ players are either defensive or attack oriented but Italian players are so flexible that a defensive move can be quickly moved into a counter-attack in a flash. As such this allows them to position themselves higher up the pitch to disturb the opponent’s play. When Spain cannot play their own game, they get disoriented especially when they have to chase the attacking Italian players.

The 2d biggest factor in my view is the attitude of the Spanish team and their coach. I think he was so arrogant that he sent out a team that only wanted to play their own game completely ignoring Italian’s tactics and strength. Unfortunately also this team is not as strong as the one in 2008 to 2012 in terms of players and clearly on the vane.

The reason why Germany used to struggle previously against them was also due to the same fact that when Germany couldn’t play their own game in midfield and have to deal with Italian attacks, they lose their direction.

I think the secret to beat Italians is to counter their midfield by playing 3-5-2 and take a less conservative approach. I think this what was tried by Joachim in the March friendly. We can expect Italy to press Boateng and Hummels and make Neuer play the ball to defenders and also block the passing channel to Kroos. They might leave Khedira free in order to trap him as he’s slow and not as good passer as Kroos.

This is not a tactic that Germany has not encountered before (esp in the Brazil 2014) so the secret to beat the system is to use the attack the wing with pace and avoid pumping balls to their CBs. It is important that the full backs also move up to midfield to offer passing options rather than their usual gung-ho approach of wing play.

As for the team, we can expect Oezil to be marked so it is better move him to the wings and keep switching with Draxler. Mueller should play deeper, fill the holes, do some midfield marking and chase the second balls.

Also the pressing of the CBs is vital to deny them to start their build up as well as counter-press.

DSDD June 29, 2016 um 2:12 am

I don’t like that in this article Italy’s salir jugando doesn’t receive enough credit for this win. I think one of the keys of this game was that Italy managed to get out of Spain’s pressure in a very nice and clean way. Rarely the ball has been kicked out, in the very first phase of build-up Spain tried to press Italy high but Italy always escaped out of it cleanly so that they had a lot of space after they got over this high pressing wave. This was possible because Spain sometimes used their cover-shadows badly and also because Italy’s positional adaptation was very flexible and good. Especially the De Rossi-back three constellation was very successful (obv. also thanks to the high work rate of the WB and b2b-players).

So all in all, not only the defending was incredibly intense but also their possession-play was on a very high level.

Stewie Brian June 29, 2016 um 7:46 am

Agreed.. Also, the wingbacks released forward passes very quickly, almost always first time. So the Italians beat the high press with extra defender and bypassed Spain’s midfield, going straight for the throat (2v2 situation with Pique and Ramos)..

It’s not a new strategy, but no one does it like the Italians. And it all starts ( and ends) with the BBC of Juventus 🙂

Silas June 28, 2016 um 8:50 pm

This is a fantastic piece of analysis and absolutely on target. But I have a question – why was Spain’s counterpressing so ineffective?

CE June 29, 2016 um 7:46 am

I should re-watch a few situations, but I can definitely say that on occasions they didn’t have enough players “behind the ball” or were simply out of position. In the next round, Germany should protect the backspace more intensively when they want to establish dominance. Otherwise Italy could again create transition attacks and get Pellè as well as Éder involved.

Arthur June 28, 2016 um 1:27 pm

Vlt. war das größte Problem der Spanier der langsame Spielaufbau im ersten Drittel? Spanien hatte große Schwierigkeiten das hohe Pressing der Italiner zu umspielen, weil sie sich oft unpassend frei liefen und die Innenvertediger eigentlich nie dynamisch nach vorne stoßen konnten. Desweiteren haben sie es auch nicht geschafft, die italienische Defensivformation horizontal auseinanderzuziehen. Selten gab es aussichtsreiche Verlagerungsoptionen oder mal dynamische Tempowechsel.

Sorry, kann das nicht auf Englisch schreiben….