Leicester City: Smart as eleven foxes

They are leading the Premier League by a margin of seven points and seem to be the hottest thing in English football right now. This is the Spielverlagerung analysis of Leicester City…

I personally remember Claudio Ranieri when he was the Chelsea head coach in the early 2000s. In a Champions League semi-final encounter with Monaco in 2004, Didier Deschamps outcoached him roundly. It was the time when Roman Abramovich became the man in charge at the Blues, and there was no room for a dinosaur such as Ranieri who could not keep up with young guns like Deschamps or José Mourinho, his eventual successor.

Ranieri continued his journey across Europe, managing six clubs in the next ten years. He ended up in Greece, where the football association appointed him as national coach after the 2014 FIFA World Cup, only to fire him a few months later following a defeat against the Faroe Islands, of all teams.

At this point, a coach in his sixties should probably think about retirement. Ranieri, however, returned to England. On July 13 2015, Leicester City, who had barely escaped relegation from the Premier League the season before, announced him as the club’s new manager on a three-year contract.

A supposedly washed-up coach with a bunch of journeymen wanted to solidify their position in the league. They have beaten all expectations, including their own. Leicester’s fans now chant Ranieri’s name with passion. The old man earned the respect of many. Is it a modern football fairy tale or just the consequence of circumstances?

Squad

In a wider European context, one could question if a club that signs players such as Shinji Okazaki or Gökhan Inler can even be considered the underdog. Okazaki was an important piece of the puzzle at Mainz before he joined Leicester. Inler was linked to teams like Schalke prior to his signing. Maybe Leicester are an underdog in the Premier League, where huge television deals provide money clubs in the rest of Europe, even in the Bundesliga, simply don’t have. Yet, on a grand scale, this team possesses significant quality.

The Foxes spent almost £40m last summer. The old core of the team remained unchanged, yet the club added important players to their squad, who turned out to be crucial for their success this season. Having said that, Leicester have a relatively small roster that got even thinner in the winter when Ritchie de Laet and Andrej Kramarić left on loan deals.

Unlike his stint at Chelsea, where constant rotation earned him the moniker of “the Tinkerman,” Ranieri now seemingly likes to operate with a small circle of players. He barely changes the starting XI or makes use of a heavy rotation policy. He trusts the 16 to 20 players who have carried his system so far. Many of them flew under the radar prior to his season. The likes of Riyad Mahrez and Jamie Vardy didn’t even play for first division teams before they came to Leicester. Now they, as well as team-mate N’Golo Kanté are among the six nominees for the PFA Players’ POTY.

Line-up

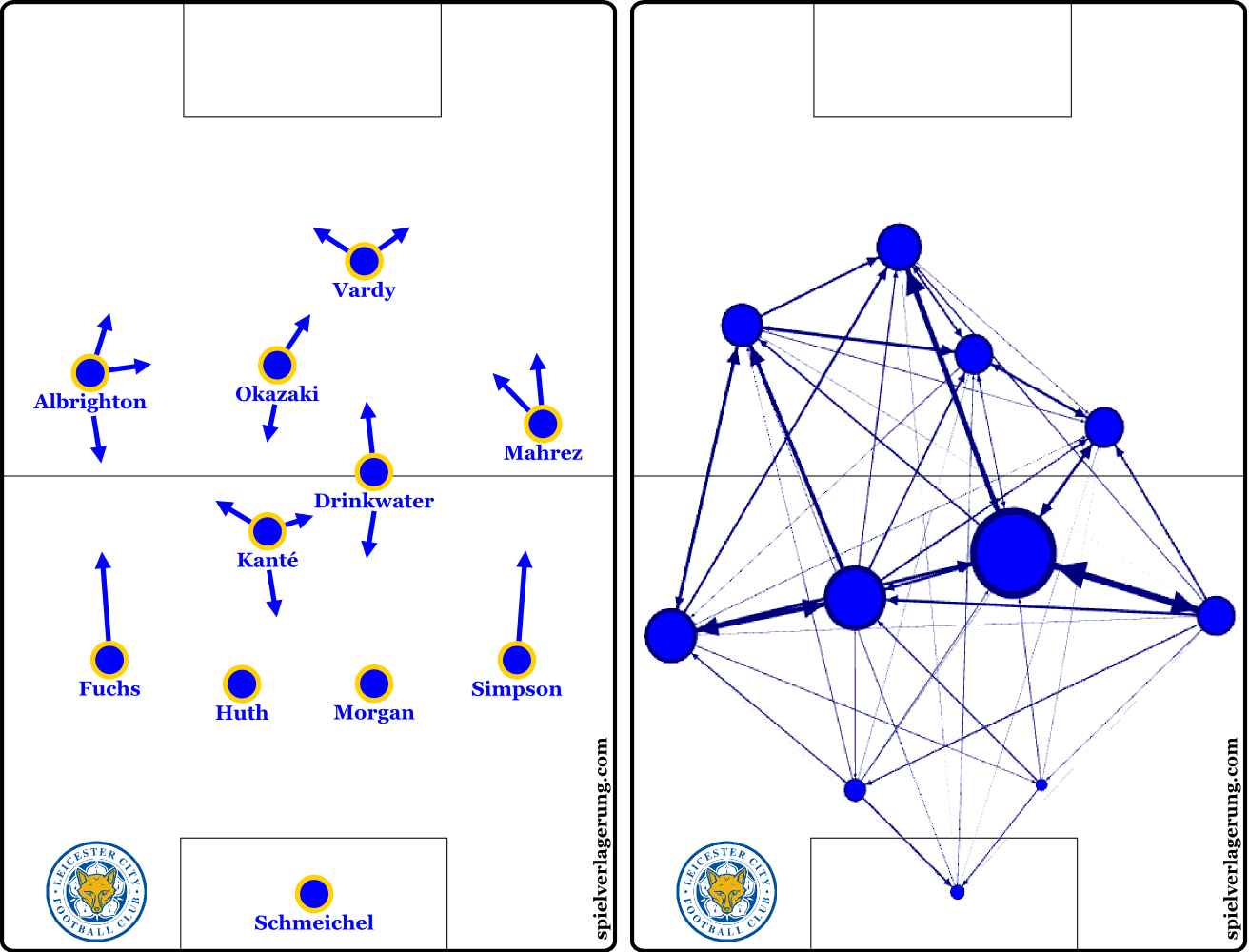

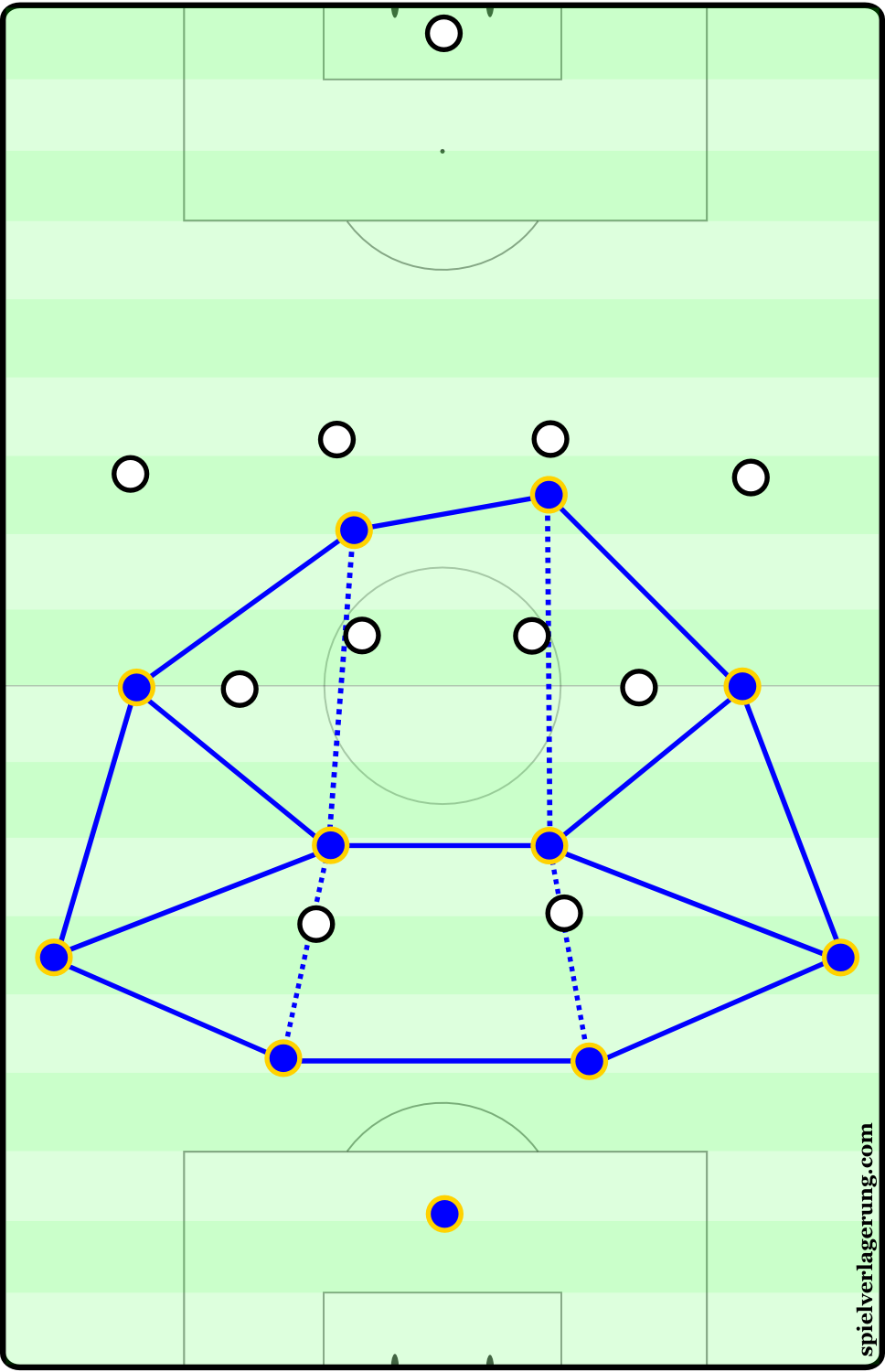

Ranieri consistently sticks to the system he introduced when beginning his stint at the club. Leicester’s 4-4-2 is a classic English formation that usually has significant flaws, especially when employed by a team who want to put emphasis on possession football. In Leicester’s case, the 4-4-2 serves very well as a base for their concept.

The Italian head coach changed his team’s shape only a few times, e.g. against Manchester City last December when he utilised a 4-1-4-1 formation which, however, limited the lone striker’s influence and isolated him from the rest of the team.

Ranieri’s 4-4-2 provides more presence upfront, while it is also easy to maintain spatial compactness in defence. The shape does not change after turning the ball over, though it can be referred to as 4-4-1-1 in defence, but this is just a matter of how one uses numbering in regards to formations.

Players’ influence

From back to front, let’s take a quick look at Ranieri’s key players on the pitch. Both centre-backs, Robert Huth and skipper Wes Morgan, usually have an advantage in aerial duels, but the two rather inflexible defenders should not leave the centre too often. Their skill sets certainly suit Leicester’s defensive approach, although a lack of speed hinders them from playing a higher back line to squeeze the space between them and the midfielders even more. Both Huth and Morgan are normally at the end of an opponents’ attacking play, when Leicester’s centre-backs only have to clear crossed passes in a best-case scenario, as the Foxes intend to contain central attacks at all cost.

Left-back Christian Fuchs is regarded as one of the best full-backs in England these days, only months after he seemed to be a player on the decline when leaving Schalke. The Austria international is one-dimensional, yet has almost perfect attributes to serve Ranieri’s system well, given his durability and solid speed compared to other full-backs. Fuchs ousted home-grown player Jeff Schlupp after the first phase of the season and has not lost his spot since. Danny Simpson on the other side of the back four possesses similar strengths.

In midfield, Kanté and Danny Drinkwater complement each other beautifully, so there is no conflict of interest due to similar intentions on the pitch. Kanté is the workhorse in a more defensive role, while Drinkwater, not less persistent, has become a box-to-box authority who links up with every team-mate on the pitch.

On the wings, Marc Albrighton has a better understanding of group-tactical processes than Mahrez, who appears to be the best pure footballer of the team, but is not gifted with the highest football IQ, which doesn’t hinder him from breaking through opposing defences on a regular basis. He often acts as a soloist who is isolated from the rest of the team and has no connection to his team-mates. That’s why he appears to be out on his own on many occasions.

Albrighton, on the other side, is not as talented with the ball at his feet as Mahrez, but the 26-year-old knows how to find open spaces and when to use them properly. Solely from a team standpoint, Albrighton can support Leicester’s strikers better than Mahrez, who, however, offers a threat to every defence in the league, which makes him valuable to this team in his own way. Particularly if Vardy is asked to frequently drift to the right side, Mahrez can pick up layoff passes after moving diagonally towards the middle.

But other than that, he forces one-on-ones which does not fit to Leicester’s philosophy that well, yet he can be effective due to his technical ability and his vision for open pockets he can rush into. The Algerian international has improved in terms of end product, but remains an unknown factor if Leicester’s form declines one day.

Data via WhoScored. As always, credit goes to Ted Knutson for establishing this sort of diagram.

Up front, Okazaki has secured his spot next to Vardy, after a close battle with Leonardo Ulloa in the first half of the season. Once a clinical poacher at Mainz, the Japanese forward now interacts with Vardy with altruistic motives. In an offense with two strikers, he has the higher defensive work rate of the two.

Vardy has become a superstar in England thanks to his clean finishing and fast-paced counter-attacking style. A short and lightweight striker, Vardy outpaces the vast majority of Premier League defenders with ease, which is important to Ranieri’s pivotal strategy.

Strategic characteristics

Speaking of which, before Ranieri was able to introduce the finer points of his tactical system he had to have a basic idea, a fundament on which he could build the house. To put it simply, the idea is solely about making transitions, from the principles of counter-attacks to the shifts between single phases of pressing.

This is the concept, and it leads to their using a form of counter-dynamism, which means they react on the rhythm instead of setting the pace of a match, capitalising on the opposite force that is generated by quick transition plays.

I once read a comment on FourFourTwo where someone compared Leicester’s tactics to guerrilla warfare versus traditional armies. It is quite a stretch, but the more I think about it, the more a like the comparison. Leicester enjoy the chaos and benefit from the inflexibility of many opponents.

In a rather static environment, they don’t feel comfortable. If opponents don’t do them a favour in trying to determine the course of a match while in reality allowing Leicester to exploit openings, it has to be at least a chaotic match.

Contextually, they find ways to implant a certain impetus into the game, enabling the encounter with another team to move in the direction they want. Knowing they thrive in chaos, it can even be a goal to cause turmoil and destroy structures that otherwise could lead to a more conventional trial of strength which doesn’t usually favour Leicester.

The Foxes aren’t usually the superior side on many occasions. However, given the confidence and self-understanding they have developed, they believe in their ability to overcome obstacles, to beat a team that is more talented on paper, and to follow the plan laid out by Signore Ranieri.

And after all, the recent success has given them the confidence to even act like an experienced top-tier team, when, for instance, they drag the ball upfield or play slow one-on-ones to run down the clock in order to secure a lead. Leicester is new to the party, but that doesn’t mean they don’t learn quickly, while maintaining their special style of play.

Sacchi-esque defensive approach

As someone who started his coaching career in Italy in the mid-1980s, Arrigo Sacchi inevitably influenced Ranieri’s way of thinking of and looking at football. But not only did Sacchi affect him on a meta level, certain facets of Sacchi’s tactics find expression in Ranieri’s approach in practice today.

A clear-cut 4-4-2 with emphasis on spatial compactness is textbook Sacchi. Sports Illustrated‘s Liviu Bird pointed out the similarities in a piece in December.

“Sacchi wanted a maximum of 25 yards between his defenders and forwards and a high line that would compress the playable area of the pitch to his team’s advantage. Out of possession, the current Leicester displays similar tendencies, leaving little space for opponents to play centrally.” (Liviu Bird)

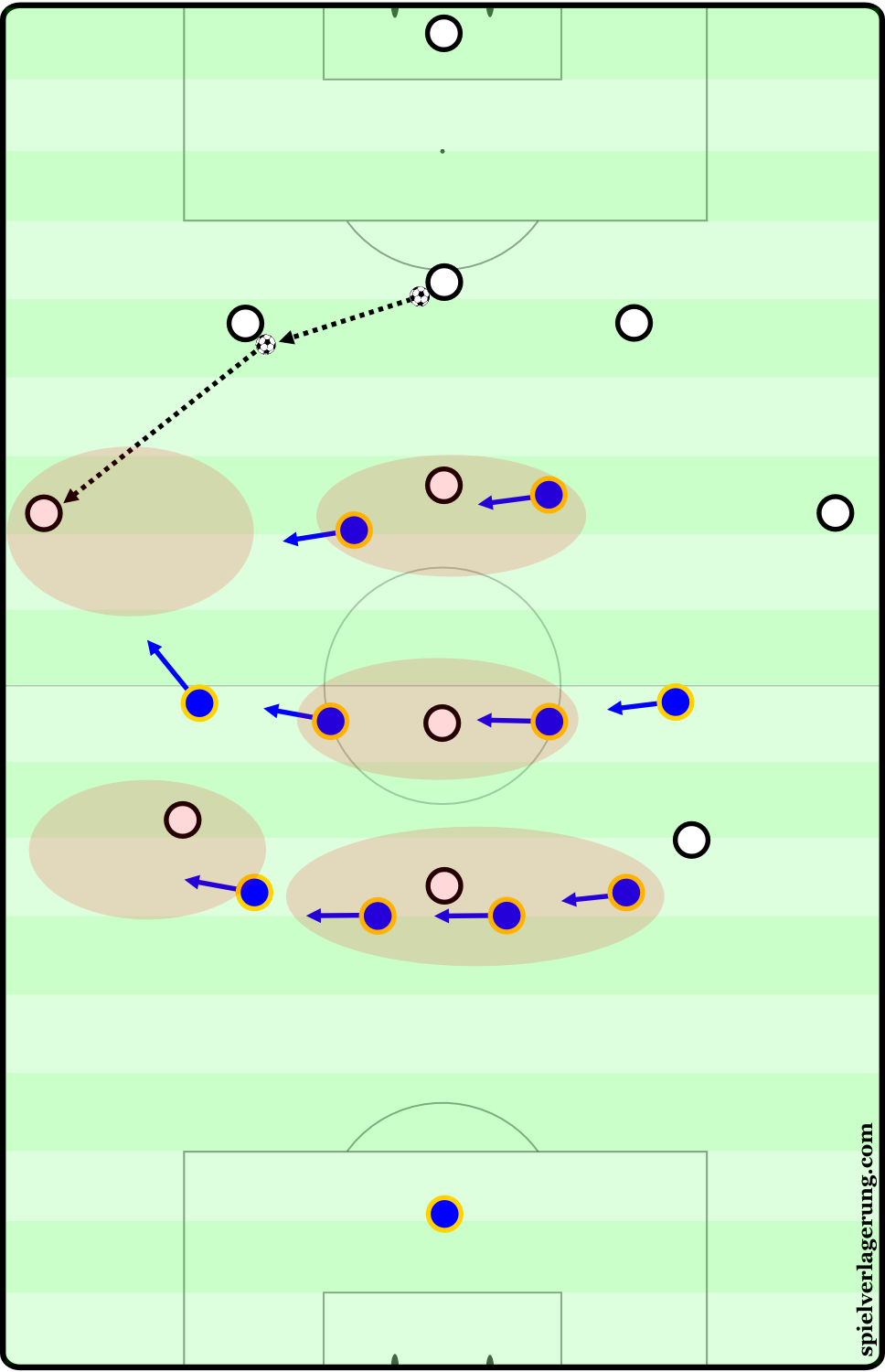

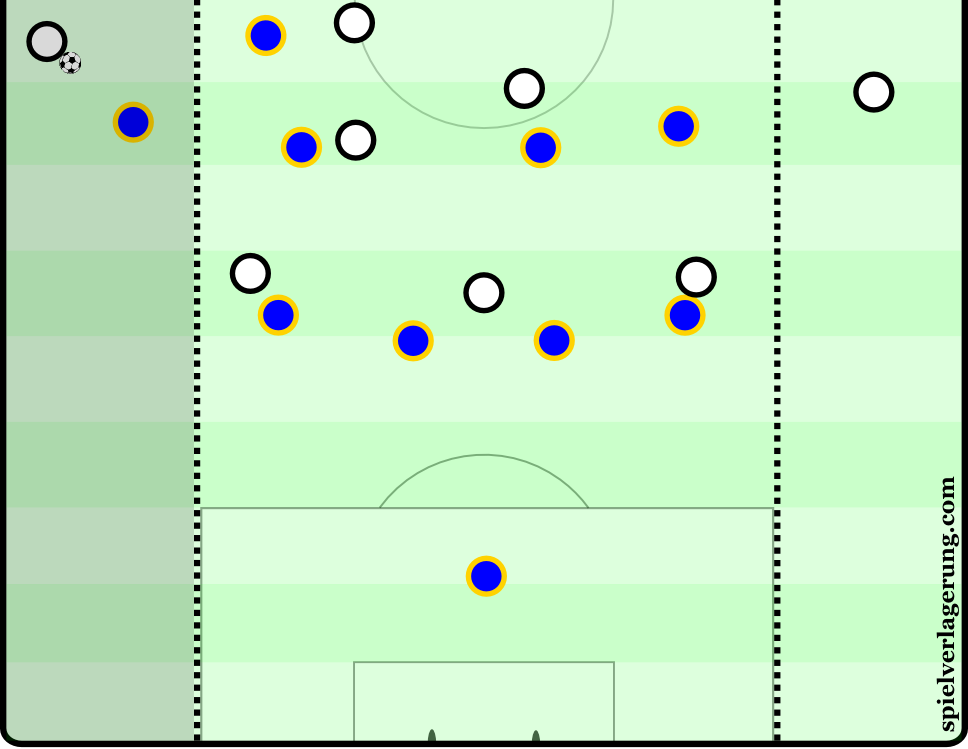

In the first phase of pressing, both forwards move laterally a lot, switching between the opposing players they are asked to man-mark in what is zone-orientated man coverage. The midfield line, meanwhile, moves in regards to the ball position and always keeps the initial shape. Only one of the wingers pushes a few yards forward if the opposing team move the ball to his side. The ball-near winger could pressure the ball-carrier on the wing by running towards him, although a strictly man-orientated approach doesn’t appear to be part of Ranieri’s plan.

Rather, he wants his advanced winger to keep a connection to the centre, while the other line of four – most of the time it is the back line – should not be wider than the penalty area. The idea of narrowing at least one line or both lines at best resembles Sacchi’s concept of compactness.

It is obvious that Ranieri divides the pitch into three vertical zones, as his team should only occupy two of them at any moment. Therefore, Leicester’s strategist puts no emphasis on a half-space-dominated concept of space. His zone-orientated man-marking scheme paired with said focus on vertical compactness lead to spatial control in the middle of the park.

Leicester’s centre-midfielders cover opposing players as long as they are positioned near them. They follow opposite midfielders, who drop back to escape the tight zones, only to the own forward line and go back in position quickly after letting the opposing player leave the protected area.

This kind of control helps them intercept passes across the middle. First, tight man coverage closes down passing options. Second, the opponents’ natural reaction by leaving the centre leads to Leicester dominating the middle.

In the second phase of pressing, Leicester continue their ball-orientated shifting and zone-orientated man-marking, except for throw-ins where the far-side winger closes the distance to colleagues in midfield, so he could run into higher central zones in case Leicester win the ball.

After guiding the other team towards one flank, Vardy and Okazaki threaten the opponents’ backspace, being positioned on a diagonal line, with the centre-forward on the far side higher up the pitch. The ball-near forward uses backwards pressing to apply pressure from behind, or he waits in the half-space next to the ball-carrier to close down two or three short-pass options and block passing lanes towards the opponents’ backfield. What is more, the rather deep position allows said centre-forward to fill in the hole in midfield if one of the centre-midfielders chases an opponent down goalwards.

After guiding the other team towards one flank, Vardy and Okazaki threaten the opponents’ backspace, being positioned on a diagonal line, with the centre-forward on the far side higher up the pitch. The ball-near forward uses backwards pressing to apply pressure from behind, or he waits in the half-space next to the ball-carrier to close down two or three short-pass options and block passing lanes towards the opponents’ backfield. What is more, the rather deep position allows said centre-forward to fill in the hole in midfield if one of the centre-midfielders chases an opponent down goalwards.

As for Leicester’s full-backs, they are usually positioned centrally and leave their position only occasionally, when moving towards the touchline after an opposing winger received the ball behind Leicester’s midfield line or the opposing team played a quick transition attack through the wing. If a full-back charges forward to pressure the ball-carrier, a 3-5-2 emerges for a moment – until the nearby midfielder drops into the full-back’s initial position.

Otherwise, both full-backs keep their positions near the centre-backs to narrow the gaps for through balls. It is also necessary to keep contact with Huth and Morgan, as both centre-backs shouldn’t leave the middle, because of their vulnerability in open spaces.

Otherwise, both full-backs keep their positions near the centre-backs to narrow the gaps for through balls. It is also necessary to keep contact with Huth and Morgan, as both centre-backs shouldn’t leave the middle, because of their vulnerability in open spaces.

Once an opposing team are able to pull one of them out of the backline, Leicester are in major trouble.

Both centre-backs are physically impressive, yet lack speed and agility. That’s why Leicester’s back line cannot be too high in order to avoid too many long balls over the top and in behind the centre-backs.

All in all, Leicester’s defensive approach is not spectacular, though it offers so many little details and group tactical aspects that make it tough to get in behind the back line through the middle and create high quality goal scoring opportunities.

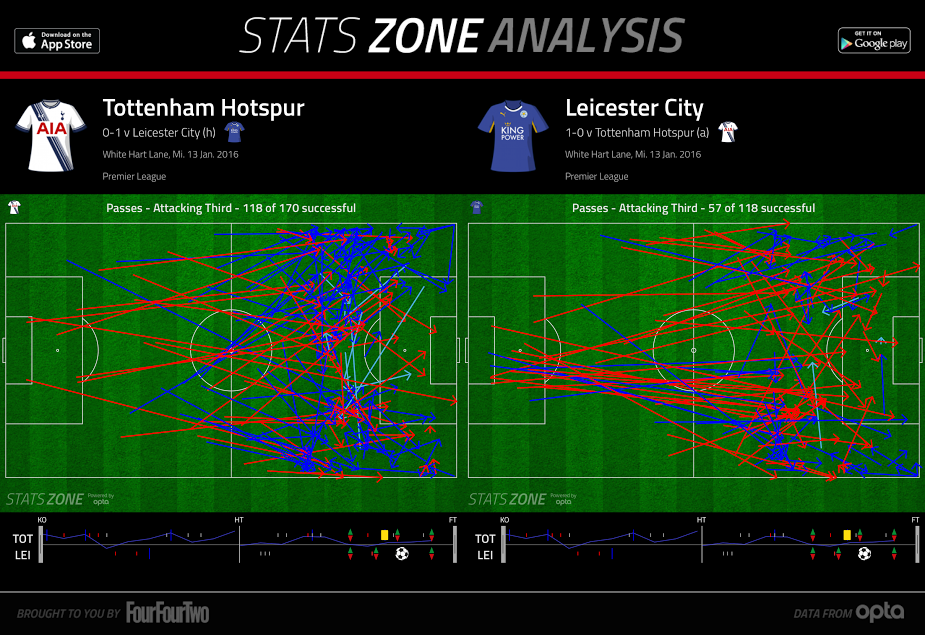

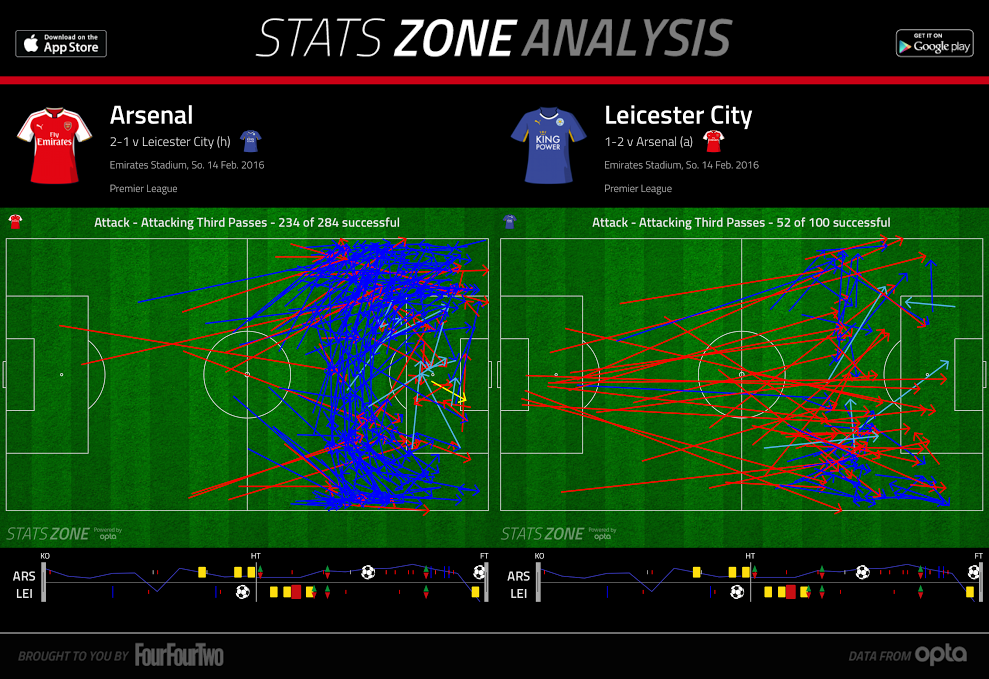

Arsenal were able to play through Leicester number six space, but couldn’t enter the penalty area that often. Tottenham completely failed to come through the middle. Graphics by Stats Zone.

Statsbomb‘s James Yorke recently mentioned on Twitter that Leicester’s opponents had an average shot conversion rate of 3.4 percent in the matches against the Foxes from this season’s midpoint onwards.

Pressing is the best playmaker

Their build-up play is as stale as their defensive system is solid. Consequently, pressing and counterpressing have to create goal scoring chances, more or less following Jürgen Klopp’s credo of counterpressing as the best playmaker.

Premier League teams are already primarily focused on wing attacks, so they lack the required structure to build up across the middle. It is, therefore, easy for Leicester to guide them to the wing. Due to the diagonal staggering, their forward line occasionally offers one side, only to isolate the opposition near the touchline.

“Different cultures, levels and leagues have different patterns. Some leagues vary a huge amount, others have teams playing in very similar systems. … Thus, when building the game model it’s important to reflect what this means tactically and what the strengths and weaknesses of the oppositional systems are.” (Spielverlagerung’s René Marić in his piece on ‘How to create a game model’)

Once the opponents are on the wing, it becomes hard to move the ball around Leicester’s block thanks to the centre-forwards’ backwards pressing. Midfielders are two against three quite often, yet squeezing the space provides spatial compactness, which, as explained, forces the opposing midfielders to move back. Thus, Leicester gain control over the centre.

Overall, the transition within the process of pressing is very smooth. It divides Leicester from the vast majority of Premier League teams. To achieve their aim of slowing down opposing attacks on the wing, as opponents move into dead ends, it is indispensable to transform the formation fluently.

Both strikers track the ball, while staying close to the opposing midfielders and making use of cover shadows. The one opposing midfielder who is man-marked by a Leicester midfielder drops back, which gives the Foxes’ midfield the opportunity to control the passing lanes through the centre. After the opposing team played the ball down the flank, Leicester close the space near the ball, while both centre-forwards position themselves intelligently, so they have access to several opponents in the backfield.

The ultimate goal is to set up counter-attacks. In accordance to their general strategy, Leicester appear to be sitting deep passively, but by employing little tricks they gain a huge advantage. As for many matches in this season, turnovers were inevitable.

Comparison of Leicester City’s shots from ‘fast’ and ‘deep’ attacks in 2014-2015 and 2015-2016. Points are coloured by their expected goal value (red = higher xG, lighter = lower xG). Diagram courtesy of Will Gürpınar-Morgan. Read his piece on Leicester here.

Leicester’s Busquets

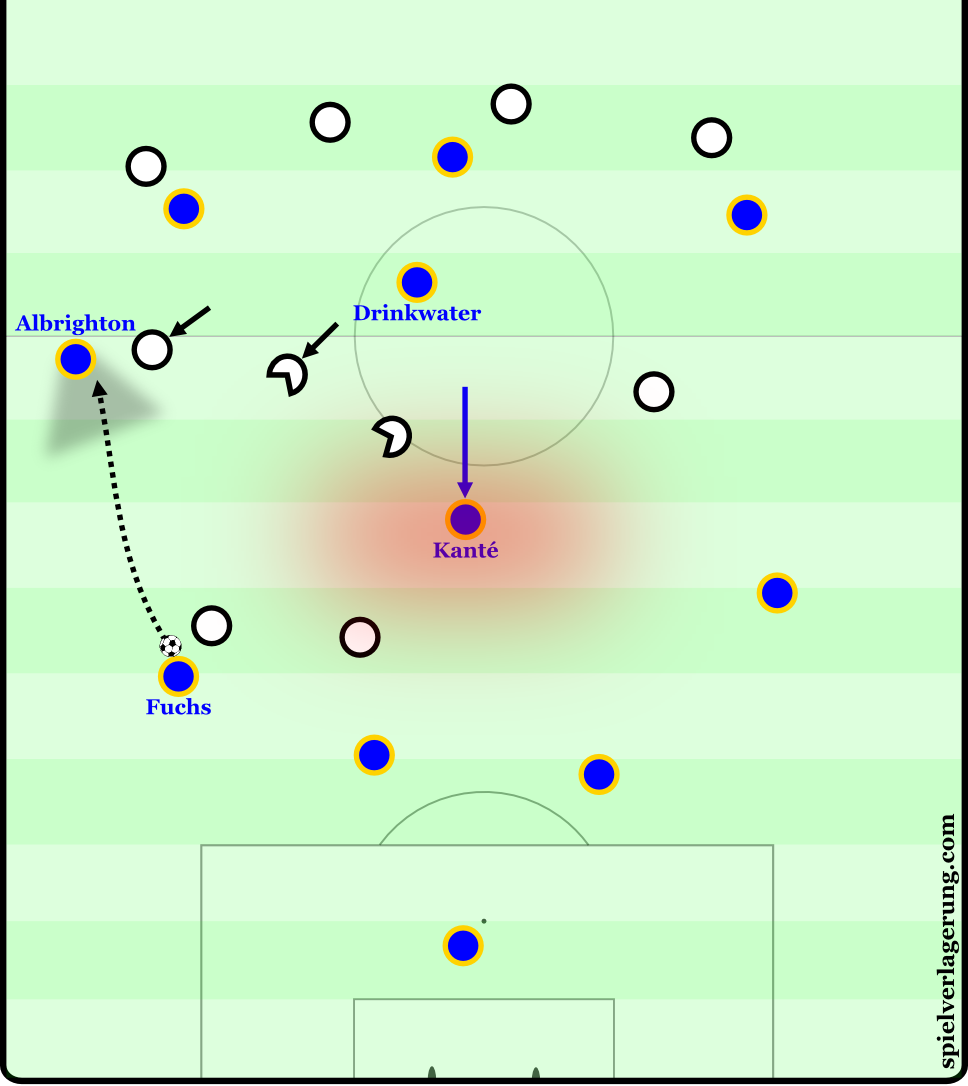

After winning the ball, both full-backs usually stay deep for a moment, protecting the advancing team-mates and offering passing options in backfield. But ultimately all players, except for the two centre-backs, move upfield to preserve a certain degree of compactness. Drinkwater and especially Kanté are the pivotal points in both defensive and offensive transition.

Speaking of him, Kanté is the heart of the team. Once reduced to his fitness and sturdiness in defensive one-on-ones, now his importance, defensively and offensively, has become blatantly obvious. Of course, the French international doesn’t have the presence of a Sergio Busquets, but he is as essential for Leicester as Busquets is for his team. And, moreover, both share common strengths, although on different levels.

Kanté is mostly convenient to his team and doesn’t serve own purposes. In midfield, he has to protect the more attacking-minded Drinkwater, who sometimes tends to be overaggressive in offensive transition, which is, on the other side, a good aspect, considering Leicester’s reliance on quick attacks after gaining ball possession.

In addition, Kanté is crucial for their counterpressing efficiency, as he usually sits in the shadow of attacking players and lies in wait for vertical passes from the opposition while reading the eyes of a potential passer – similar to a linebacker or safety who reads the quarterback’s eyes.

Afterwards, the Frenchman pitches in the passing lane explosively. As far as counterpressing goes, Kanté, as well as Drinkwater to some extent, has the intuition for rather chaotic situations. If Leicester cannot simply regain ball possession with their pressing approach, a back-and-forth between them and the opponents can occur in the middle of the field, with many changes of possession.

In this context, both centre-midfielders are not only great at winning one-on-ones, but they also have the required spatial and positional awareness to sit back for a moment before rushing out of the backfield in order to surprise the opposing team. It looks like the other team could control the situation, but in fact Leicester’s midfielders just make a feint by pretending to start sitting deep in a waiting position.

Ranieri’s men blur the border between illusion and reality, competing with straightforward Premier League teams with an in-your-face-mentality and therefore with a tendency to walk right into traps without looking left and right.

Sans Kanté, the Foxes couldn’t work that effectively. The 25-year-old does all the little things right – like dropping a few yards back, after the ball moved to one of the wingers, to offer a passing option in backfield, avoiding the threat of an immediate loss of possession. As opposed to Drinkwater, Kanté often chooses the safe option at first glance, yet ultimately helps his team to maintain the ball-circulation or simply helps his team-mates to make the right decision.

Kanté is basically an assistant all over the pitch. He has a hand in all things that happen. To put it in a nutshell, Kanté is football.

Blind understanding

The publicly most discussed person is, however, Vardy. Even though from a pure tactical standpoint, it may seem to be unfair to put Vardy over Kanté, many of his performances and consequently many of his numbers are impressive.

Data via WhoScored.

Analyst Will Gürpınar-Morgan underlined in his recent piece, that Vardy is the most effective fast-attacking player over the past four Premier League seasons, with 0.15 fast-attacking expected goals per 90 minutes. In terms of counter-attacking goals, Vardy is second over the past four years with 0.12.

“Vardy’s overall open-play expected goals per 90 minutes stands at 0.26 by my numbers over the past two seasons, so over half of his xG per 90 comes from getting on the end of fast-attacking moves.” (Will Gürpınar-Morgan)

In this regard, many people wonder how Leicester are able to find the out-balls from a deep block, as most of their opening balls seem to accurately go to team-mates up the pitch. There has to be some sort of tactical trigger that gives them the advantage over the defending team.

Indeed, there is, yet it is not the moment of the interception or the turnover in general, but rather the moment prior to that already triggers certain mechanism thanks to the anticipation of the players upfront. Having already turned to make runs before the players at the back can send the ball into the wider areas before or behind the offside line, it shows the good reflexes Leicester’s attacking players, Mahrez and Vardy in particular, have.

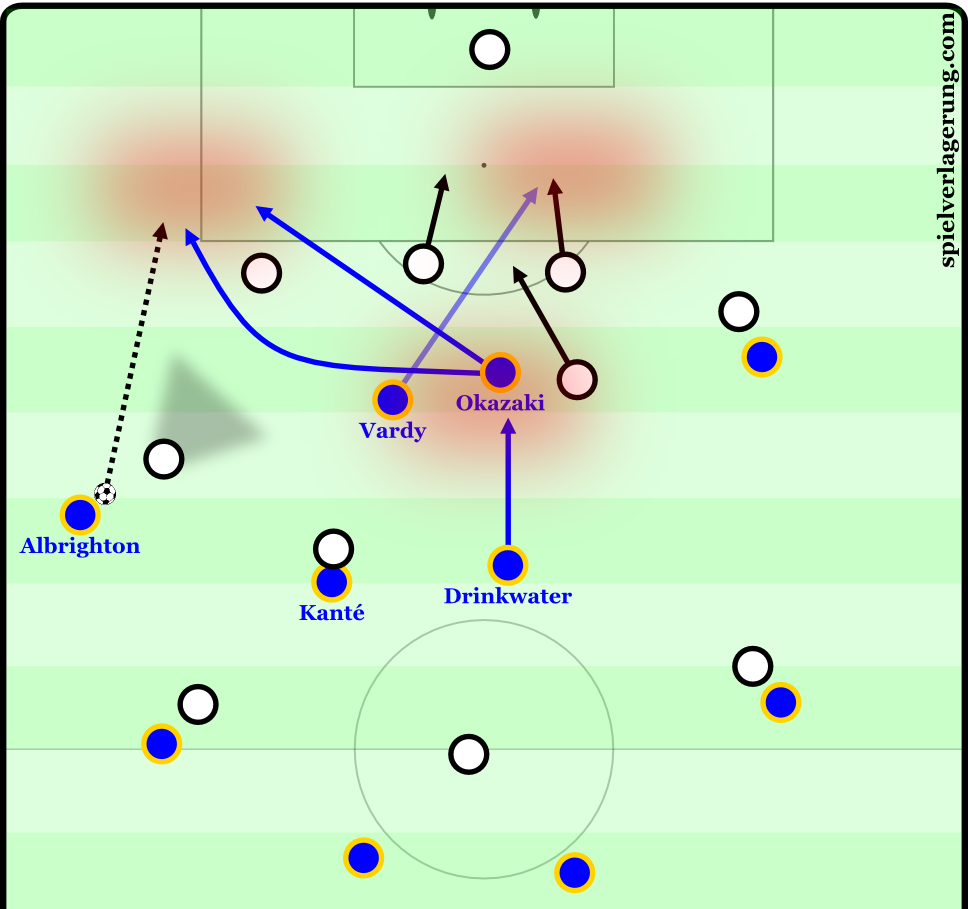

What is more, these frequent counter-attacks demonstrate a blind understanding between midfield and offense. In addition to Vardy, who always waits upfront, and Okazaki, his partner in crime, both wingers usually advance really quickly, so Leicester can overload the upper wing zone, that is the main area of a particular counterattack, with two or even three players. In contrast to both full-backs, Mahrez and Albrighton don’t hesitate when it comes to making quick runs to initiate these counter-attacks and therefore overwhelm the opposing team, whose defenders stand with their backs to their goal and have to start out of static positions.

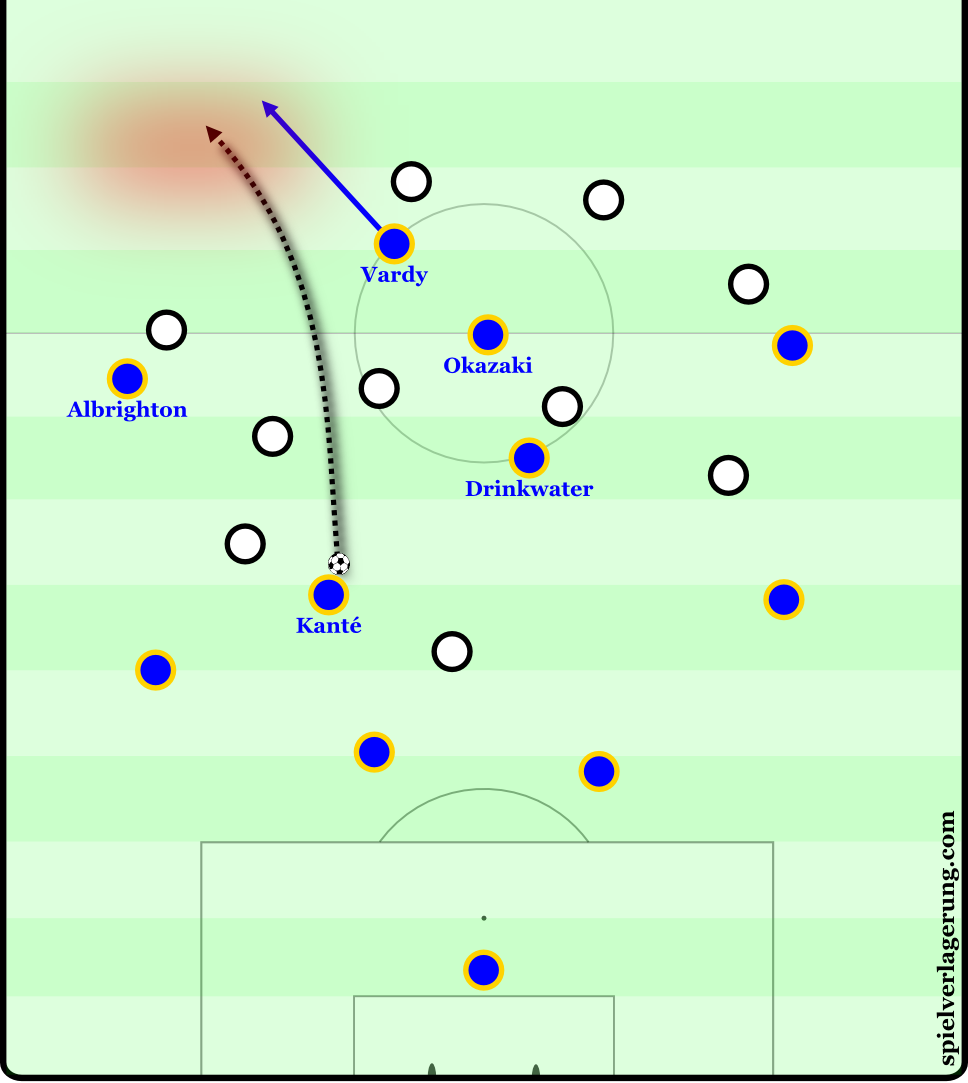

Vardy, as the main target player, usually drifts outwardly to receive a long pass, but keeps an eye on the direct way towards the goal. He can rush towards the touchline, but tries to stay within the half-space. Particularly in situations when Vardy is on his own, it wouldn’t make sense to try to split the centre-backs when there is nobody he could play to. The route between the centre of the pitch and outside lane has become a Vardy trademark move.

Vardy has been successful with this route repeatedly. Graphic by Stats Zone.

Okazaki or any other second striker serves as an elementary component in terms of how Leicester set up these Vardy shots. Plus, he can help Vardy out if Leicester’s top goal scorer cannot attempt a shot on his own. Okazaki either drops back to offer the midfielders a short passing outlet for a moment, or drifts towards the zone Vardy has entered to help his team-mate by setting up a short combination play, or he makes a diagonal run into the danger zone staying ready for any kind of cross-field pass.

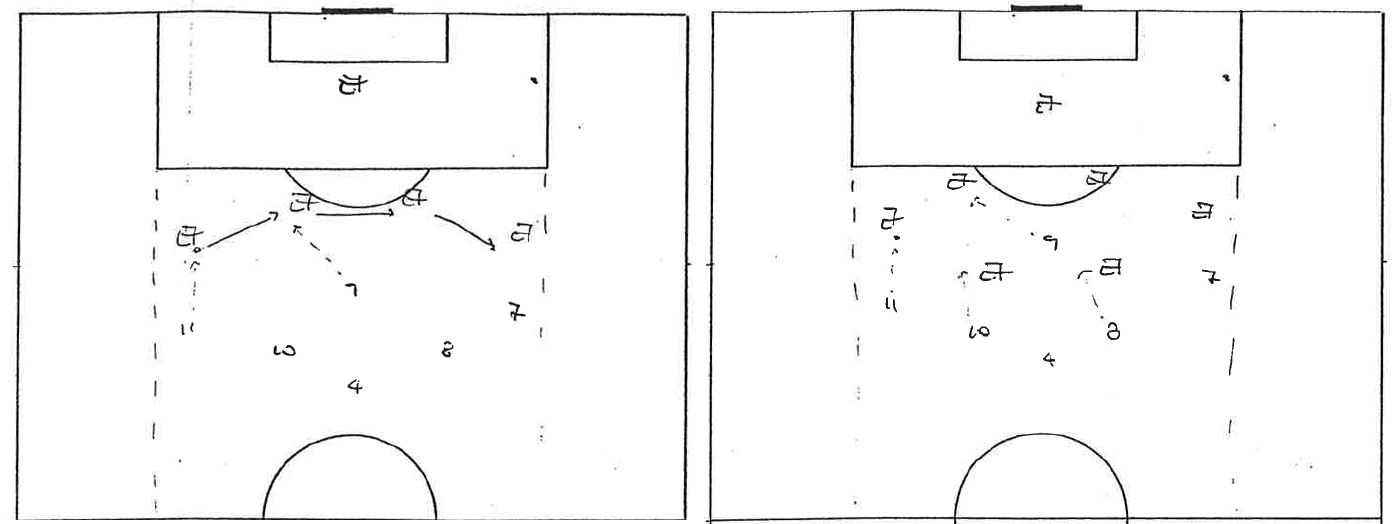

Diagram courtesy of David Sumpter (Soccermatics).

Every move happens in the light of three elements Leicester’s players always keep in mind: the importance of pace and directness, plus the avoidance of pressure thanks to quick passes into open spaces. And their routine has led to an execution of their style on a consistent basis.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean the Foxes don’t have answers if they cannot execute their initial plan. Vardy and his colleagues from time to time can be great at improvising fast-attacking combination plays, without utilising any of the designed plays.

Nevertheless, they are more comfortable when following a predefined plan and Ranieri provides them with more than one. For instance, if Leicester aren’t able to accelerate from a deep position or by knocking the ball down an outside lane, a winger or full-back who hugs the touchline often receives the ball, while one of the centre-forwards charges upfield. Then a diagonal pass into the space next to the opposing backline or behind the nearby full-back sets another play in motion, as the defence has to react quickly, often giving up the backspace which then is open for Drinkwater or the second striker who doesn’t have to rush into the box in a predictable manner, even though these runs let the defenders’ eyes rivet on him.

Despite both full-backs tending to stay deep in the first few moments after their team regain ball possession, their overlapping runs really help to give width in the final third and to expand the passing patterns. First, Fuchs and Simpson are deep to get involved in the ball circulation if necessary. Second, after advancing they then offer options at the halfway line. Third and last, they penetrate the high wing zones next to the opposing penalty are.

Full-backs who provide width combined with four attacking players who run diagonal routes to annihilate man-marking schemes – zone-orientated man-marking as preferred by many English teams – and overwhelm rigid formations, plus at least one on-rushing midfielder result in a dynamic structure which isn’t highly sophisticated, but largely effective, as the constant quality of their shots gives evidence. Only 23.96 percent of Leicester’s shots got blocked by opponents, far less than any of the other title contenders. Leicester are the fifth-best Premier League team in this category.

To point out one aspect that is not perfect as of now, Leicester are so focused on playing said diagonal balls into the designated landing zones that they quite often neglect an open inside lane. It has worked so well that they probably ignore alternatives.

Speaking of alternatives, crossed passes belong to their style, yet Leicester use these only when it is situationally required. Although long balls are crucial elements of their attacking style, goalkeeper punts aren’t utilised effectively. Typically, the ‘keeper knocks the ball over the heads of both centre-forwards, without them as well as the midfielders being positioned properly and therefore compactly enough to win rebounds or force duels.

Set-pieces can be of importance, though Leicester don’t rely on any specific tactics other than having two towers in Huth and Morgan who, of course, are always likely to score after crossed free-kicks or corners. Besides free-kicks, corners and conventional crosses, which can lead to goal scoring opportunities, Fuchs’ throw-ins have been a consciously used weapon so far, because his throws have almost the length and pace of crossed passes.

Knowing your limits

It remains questionable how long Leicester can perform with their unique style at the top. Because, on a downside, their build-up play is improvable, as they suffer from many losses of possession in static environments. With both full-backs being positioned deep and all attacking players normally charging forward in the initial build-up, there is a lack of connection between the first and the forward line. Only if opponents press with only one player upfront, one of Leicester’s centre-backs dares to move a couple of yards forward.

No matter against whom they play, Leicester stick to their strategy of constant wing attacks. Graphic by Stats Zone.

But normally the success of their build-up play, when not having the opportunity to capitalise on transitional situations, relies on both centre-midfielders, who begin every spell of possession in the middle next to each other. From there they start moving vertically. Kanté often drops back to get in front of the opposing block, escaping the pressure to screen the field, though the possibility of build-up play via ground passes is reduced.

In fact, they deprive themselves of the possibility to add more variables to their attacking game, which isn’t shockingly surprising when speaking of a Premier League team. Even when considering their altered status, that doesn’t necessarily mean that Leicester are forced to be more creative when in possession of the ball. Since the beginning of the year, their average percentage of possession hasn’t increased significantly, as this is due to the characteristic of the league and due to Leicester’s ability to make matches chaotic.

“Over games 17 to 28 in the Premier League, their shots from possessions starting in their own half tumbled by 50%. Meanwhile, the expected goals from these possessions – a measure of how good their chances were – fell by 25%.” (Sean Ingle, Guardian.com)

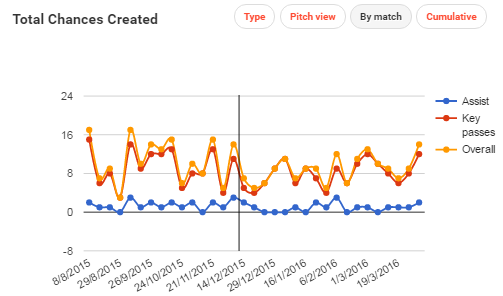

Number of created chances declined after Matchday 17. Diagram by Squawka.

In recent weeks, Leicester’s matches gave the impression that opponents were more successful with pressing in midfield. However, while the total number of shots from counter-attacks fell, the quality of shots taken following counter-attacks rose.

The Foxes lay emphasis on long balls that can bypass a lot of players and bridge much space at once. Even though it hasn’t become easier to deploy these trademark balls, attacks that get through the press are still a dangerous threat to every defence.

“Currently, the Foxes have about the same expected goals total per match as Tottenham in a simple shots-based model. But they also take about a quarter fewer shots per match than Tottenham. And, as you’d expect, their expected goals per shot are about a third higher and also the highest in the league.” (Dan Altman)

Where shall they end up?

Almost everyone already expected a decline after Christmas – a regression toward the mean, if you will. Yet, Leicester proved forecasts wrong to the delight of Ranieri and his players. Most of them stayed healthy and the Italian didn’t change his winning system.

Plus, despite the mentioned decrease of Leicester counter-attacks, a partial unwillingness among the English clubs to come up with suitable strategies against Leicester has helped them to be the second-best team in the league since Christmas and the best team point-wise overall. To answer the question from the beginning, Leicester’s success is a consequence of own achievement and external failure.

At this point, there is no reason to think Leicester’s squad will be completely picked apart, because their owners, King Power, should be willing to fund huge wages. Nevertheless, the probability is high that Leicester will finally experience a breakdown next season.

The Foxes will not only go up against high-quality competition in the Champions League, but also compete with motivated teams who could enjoy the fresh air of new coaches (Pep Guardiola, José Mourinho) or the impact of coaches who finally settle down at their clubs (Jürgen Klopp). Hope gives Atlético Madrid who are a defensive-minded side as well and who have surpassed all expectations, although the Rojiblancos have had a more talented roster.

And even if Leicester disappear from the upper third of the Premier League quickly, their 2015-2016 campaign is one for the history books.

4 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

21 May 14, 2016 um 7:17 am

Super Artikel!

Am Ende ist bei mir die Notiz, das die Leicester Spieler möglicherweise gedopt sind, nach rechts verschoben und es steht jedes einzelne wort übereinander und ist somit mühselig zu lesen, vielleicht liegts auch einfach an meinem Handy.

Izi April 21, 2016 um 9:32 pm

What I find interesting is that despite having increased their overall performance, especially their goal-scoring stats, Vardy and Mahrez both have had less successful tackles and interceptions (as can be seen in the players’ statistic in the respective diagrams). Could there be a connection of these factors or is this just a normal statistical deviation?

CE April 22, 2016 um 6:44 pm

Vardy sometimes played on wing last season. This could explain the higher number of tackles/interceptions. As for Mahrez, Leicester often guides opponents to their left side, while Mahrez isn’t involved in defensive work too heavily. Or, as you said, it may just be statistical deviaton.

Milfhunter April 17, 2016 um 9:47 pm

In my opinion, this is one of the most exciting times ever to be a football fan. Not only are we witnessing how despite the higher getting budgets of teams like Chelsea,City, Real or PSG teams like Dortmund, Atletico and Leicester are on the emergence, but also the style of football is the most exciting to watch, The game is more fast paced than ever, yet still very technical. Lazy players like Ronaldo or Ibrahimovic are dying out because every player has to work hard and press, to be a defender you must be able to pass and build up almost as good as a midfielder.