Boss the flanks

Attacking is not all about mastering one-on-one situations. It is about vision, movement, smoothness, and a sense of spaces. Something Arjen Robben has perfected.

We all know how to pull off a Robben. From the right wing, you cut inside on your strong left foot to move to a more central attacking position, using your great acceleration and agility to take on defenders until you find the space to shoot the ball with the inside of your foot, tipping it into far corner. Every attacking player would wish it was all that easy.

Arjen Robben represents a certain breed of wingers in world football. The Dutchman has only one strong foot he usually uses to pass the ball and more importantly to put the ball into the net. Normally, he plays on the right side. So he cannot just run down the outside lane and cross the ball with his right foot in the penalty area. That is everything but news. Robben is one of the most impressive inverse (or inverted) wingers we can enjoy nowadays.

And the assumption is that these players utilise diagonal movement far more often than conventional wingers. The advantages of such types of players, which had already existed for quite some time, have been discovered due to the narrowness of central space, and the likes of Robert Pires, Lionel Messi and the late Robben have shown the right way to fill that particular role.

As already mentioned, the frequent attack pattern of an inverted winger is cutting inside from the wing, which can be completed by a shot attempt with the strong foot or an accurate through ball played at an angle of 90 degrees. Even though the players have many options when they cut inside, the action pattern might be crystal-clear and even individually strong footballers could become predictable. Therefore, some players are more effective when they are fielded conventionally and frequently switch between a more classic style of play and the one inverted wingers uses. That is why, despite, for instance, a left footer plays on the left side, he can also cut inside and act like an inverted winger. However, the ability of having two feet of equal value is rather helpful.

Are conventional wingers, who just bomb up and down the pitch at express speed and knock the ball in the box when they reach the last third, a dying breed? Can we simply separate wingers into two categories?

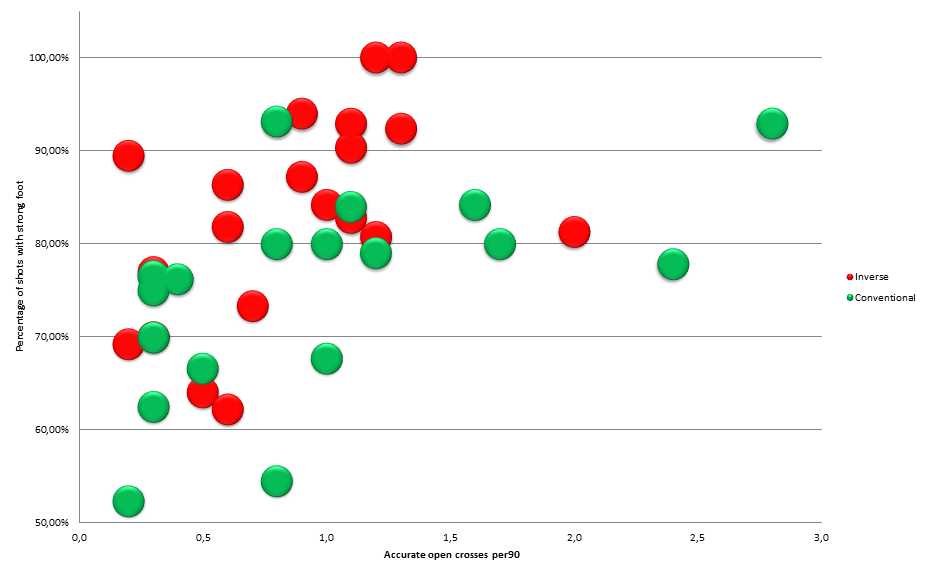

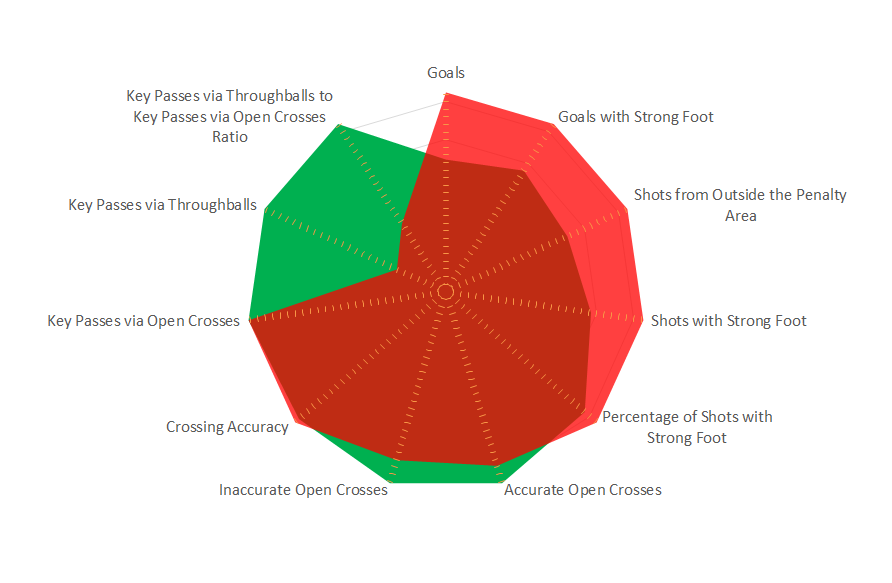

Just out of curiosity, I looked at some numbers, comparing the last season’s league stats of twenty inverse wingers with only one strong foot and twenty conventional wingers with only one strong foot. For instance, left footer Gareth Bale almost always played on the right side at Real Madrid. Thus, he belongs to the first category. In contrast, Manchester City’s Jesus Navas, who has only a strong right foot, was always fielded as attacking right winger. He belongs to the second category.

Intriguingly, the numbers do not show a clear distinction between both types of wingers. In fact, the crossing accuracy and the amount of key passes generated by open crosses are virtually identical. Of course, conventional wingers play more crosses in total, while inverse wingers can generate more shots with their strong foot as well as more shots from outside the box. Actually, the numbers of key passes that come by the way of throughballs are most interesting. According to the collected data, conventional wingers play more than four times as many key passes. The reasons for that are not obvious, but could be related to how throughballs are measured, especially when early, flat crosses cut through the defenders line. Apart from that, these data show that it is rather a question of how to use strong wingers than a matter of philosophy.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen