The bulwark of the Saints

The recent history of Southampton FC is a story of descent and resurrection, talent and sales. They had reached the end of the 2000s in League One, then built up a team with Rickie Lambert, Adam Lallana and Morgan Schneiderlin. Lambert and Lallana no longer wear the jersey of the Saints, while Schneiderlin was “convinced” after a summer outburst that he can live quite well in southern England.

Alan Shearer, Matthew Le Tissier, Wayne Bridge, Theo Walcott, Gareth Bale, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain. These names sound like an organ composition in the ears of many football fans across the island and beyond. They all came from the cradle of Southampton. Sooner or later they all left the club, except for Le Tissier, and the club was fairly compensated for them. The next generation, the generation of Luke Shaw and Calum Chambers, grabbed their bags last summer and left – in spite of the new owner. The late Markus Liebherr’s holding company DMWSL bought the club in 2009. The acquisition also carried a 10 point penalty and resulted in the descent and the resurrection.

A Look Back

The former church team is playing in the top division in England, have built an amazing training ground and surprised more than a few people last season by finishing in eighth place after 38 games. At the same time what stood out about Southampton was that they played against the typical weaknesses of many English teams. They produced new buildup formations against the man-oriented, less intense pressing movements of their opponents. The sixes increasingly dropped back laterally and eluded pressure in their 2-3-4-1 formation, with the fullbacks in a line in front of the three central midfielders to establish access early in games. Later, Schneiderlin and Co. attacked forward and created aggressive Gegenpressing shapes. This fast rhythm change in transitions often overwhelmed opponents. Furthermore, the central man orientations, as well as the ball oriented shifts of the frontmost three players, generated the necessary access at the midline against the often horizontal and vertical game plans of many Premier League teams. Up front, Lambert and wingers Lallana and Jay Rodriguez were then immediately responsible for breakthroughs. Due to the advanced positions of both full-backs, Lallana and Rodriguez often pushed slightly inwards into the ten space, where they initiated little combinations together with the evasive Lambert and tried to break through defenses.

It was a good year for the Saints – followed by a hangover in the summer as they experienced a would-be fire sale. Even their successful coach, Mauricio Pocchetino, tossed his tactics board in the car and drove straight to White Hart Lane in London. During pre-season many experts had already predicted another downfall as the club struck a deal with Ronald Koeman, a man who was not only used to being a die-hard defender but boasted more experience in the profession.

“One of the most important places in the building [New Forest] is the recruitment and analysis room and it is here where you will find Southampton’s ‘black box’, a room where matches and prospective signings from leagues around the world are analysed extensively on a video screen that looks as if it could store all of the world’s secrets.” (The Guardian, 5/11/2014, ‘Southampton are finally reaping the rewards of their long-term philosophy’, Jacob Steinberg)

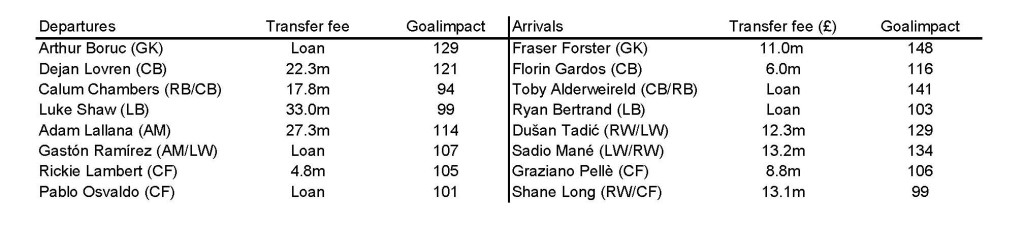

The Squad: The Italian Dancer and the Brave Little Tailor

The Saints took in £105.2 million for the five departures. The already-loaned Pablo Osvaldo was sent straight to Inter Milan in return for a loan of Saphir Taider, whose loan they terminated after less than a month. The hapless Gaston Ramirez was loaned to Hull City. All told, about 60% of the transfer proceeds were reinvested in bringing in new players. For the Croatian Dejan Lovren they got Florin Gardos from Steaua and Toby Alderweireld on loan from Atletico Madrid. Lambert and Lallana were replaced by Shane Long and Graziano Pelle as well as the two wingers Sadio Mane and Dušan Tadić. Former Newcastle and Celtic goalkeeper Fraser Forster was also purchased.

Source: Transfermarkt.co.uk

Koeman brought Pellè with him from Feyenoord and the 29 year-old, who was recently called up to the national team for the first time in October, has excelled on the Premier League stage after an unsettled career. He scored 55 goals in 66 games for Rotterdam and £8.8 million later the 6’ 4” bull has plowed through the penalty areas in England. In the first ten game days he scored 6 goals. However, likening him to a “bull” in the penalty area does not capture him completely. At the age of 11, Pellè, the former youth champion in Latin American dance, decided on taking the path to a career in football. He has shown repeatedly that he hasn’t quite lost his dancer’s hips when he evasively holds the ball up during transitions until his teammates can arrive. One way or another he will make the Soton fans marvel at his slick flick-ons with regularity. Pellè is by no means pre-destined to be a counter striker that drives the ball towards the opponent’s goal. He clearly lacks the pace necessary for this role but is capable of pulling off Lewandowski-esque moves to keep the game alive and prevent losing the ball. Against weaker teams his brutal physicality near goal comes to fruition.

Pellè previously played at clubs like AC Cesena in the Italian Serie B and now half of Europe is talking about him. Morgan Schneiderlin has gone all the way with Southampton from League One to the Championship, where the term “football” sometimes has a primitive meaning. In 2008, the Alsatian came to southern England from his boyhood club, Racing Strasbourg. Meanwhile, his place in the French national team squad has as much a part in his letterhead as his many qualities as one of the Premier League’s strongest sixes. One may argue these superlatives, but Schneiderlin’s function as a key player in the Saints’ balance holds strong. In addition to new signing and model athlete Victor Wanyama, the Frenchman operates mostly in the left half position and this role often determines the focus of the team. If he shifts towards the ten space, Southampton press more aggressively. If he drops back as a double six, the Saints the defend in deep midfield pressing. Schneiderlin is one of the “survivors” of last year’s dream team. After the fire sale this past summer and the injury to Jay Rodriguez, Soton could not accept the 30 million pound bid from Tottenham after they had already taken Pocchetino.

“They feared the fans would burn down the stadium.” (Morgan S.)

Schneiderlin remained and is now part of a new midfield with Wanyama, Steven Davis, Jack Cork and James Ward-Prowse. The latter is the next crown jewel of the youth department and is likely to eventually be called up by Roy Hodgson. Currently, however, Ward-Prowse is out with a broken foot. Steven Davis usually plays as a higher eight or ten. The 29 year-old plays like a veteran and has always been a powerful, nimble technician who loves tight spaces. With Davis, Koeman has another important element for creating combinations up front, where the two quick wide forwards romp about next to Pellè in their 4-3-3 base formation. Koeman knew Dusan Tadic already from the Eredivisie where he played since 2010 with Groningen and most recently with Twente Enschede. His consistency in decision-making, positioning, and his passing game guarantee the Serb a regular place. His counterpart at the moment is most often the former Salzburger, Sadio Mané. The Senegalese international boycotted training with Red Bull this summer after they allegedly ignored an offer from Borussia Dortmund. In the end, the 22 year-old landed at St. Mary’s after featuring as one of the best players in Roger Schmidt’s team last year. With a £13.2 million transfer free he was also their record transfer for the summer. The benefit of having Mané is still somewhat in flux. He has already shown flashes of the pressing moves of the Schmidt school but lacks consistency in handling the ball in the final third.

Shane Long was also brought in from Hull City to bolster the offensive department. In return, they gave them Gaston Ramirez. The latter was rather unhappy at Saints. Although he is an essential component of the Uruguayan national team and was key at Bologna he was clearly below Lallana on the pecking order last year. The £13.2 million fee has not paid for itself, which you can assume from the Pablo Osvaldo transfer in the summer of 2013. In the meantime, Shane Long is a less exciting transfer but conceals a lack of width in the squad. Long has played in the English top leagues since 2005, catching the eye with a quasi-Irish style, but mixed with a little more technical class. Under Koeman, Long has been deployed on the wing again as Pellè seems to have established himself centrally.

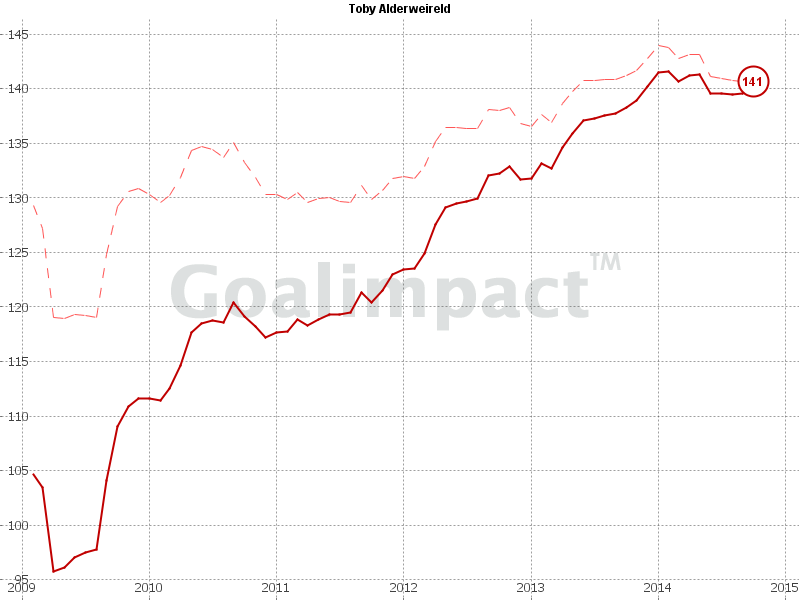

Toby Alderweireld’s Goalimpact Chart

Speaking of squad depth, the whole squad has been reduced. In addition to the previously-mentioned departures, other players left the club completely or went out on loan. The losses at full-back were resolved in a rather unspectacular fashion. Nathaniel Clyne moved into the starting role and Ryan Bertrand was taken on loan from Chelsea. The Bertrand who once belonged to Di Matteo’s rearguard in the 2012 Champions League final as a defensive left winger. Toby Alderweireld was also brought to St. Mary’s. In the Belgian national team he usually plays as right back but is better off in central defense. He certainly has his place in the lineup next to captain Jose Fonte and has emerged from the lack of playing time he experienced at Atletico Madrid where Diego Simeone was set on the starting duo of Godin and Miranda. He does exactly what Koeman asks of him, bringing stability and minimal errors to the defensive side of the game.

Manager: Hard-headed and focused on domination

TR, resident expert on Dutch football, has dealt with Koeman and has shed some light on his previous coaching positions. Koeman made his managerial debut for Ajax in December 2001. There, he often practiced a more asymmetrical 4-3-3 – although there were some more standard variants – where one of the two attackers played more in the center of the pitch and waited as an additional option for crosses. When he won the double in his first season the focus in their formation was quite simple, but then – when they lost in the CL quarter finals in 2003 to eventual winners AC Milan – along came better players in Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Wesley Sneijder. One of the two would drop back into wide positions again and again to combine with the other. Defensively Ajax were typical Koeman – his team played solid and reliably, mostly using a 4-3 shape with good synergy. The man orientations had some good and bad effects, but were not the main issue. The problem was the deep positions of the defensive sixes, which at Feyenoord was somewhat unstable and disorganized, but was used here for switching between back threes and back fives. In the important phases that season the asymmetric 4-3-3 / 4-4-2, with Steven Pienaar as a right eight, was crucial. This resulted in some good overloads on the left with players pushing into the spaces within the flatter, but consistent shapes. The results demonstrated a strength of Koeman teams; starting from a static situation and moving dangerously into the penalty area when the ball is played on the lines.

The following season saw minor changes with the wide positioning of one or both wingers being better complemented by Maxwell using the half-space more often or even occasionally pushing into the six space. The Brazilian’s evolution – which was somewhat underestimated – led to his single-minded, powerful, and very diagonal runs becoming one of the most important offensive weapons for the team. Among differences within the team – especially between the two stars, Ibrahimovic and Rafael van der Vaart – and a leadership dispute following an 0:4 loss to Bayern, a slump in the second half of the 2005 season ultimately led to the end of Koeman’s first stop. After a season at Benfica – where they lost to Porto in the league and then Barcelona in the quarterfinals of the Champions League – he won the Eredivisie title with PSV in a three-way battle on the final day of the season. Koeman played with a 4-1-4-1 formation with Jefferson Farfan as a drifting inside forward, whose threat was used for rapid counters or wing overloads with right winger Edison Mendez. Occasionally there were long balls to the left striker Arouna Kone who would knock it on for Farfan or combine with either Jason Čulina or Ibrahim Afellay pushing into the half-space. After a strong start to the following season, Koeman accepted an offer from Valencia – however, he was not happy in Spain and they were almost relegated, which winning the cup could not offset.

Following a disappointing time at AZ – following the championship won under van Gaal they found themselves once again in the nether regions of the table – Koeman joined Feyenoord for a longer stay. It was an ambivalent time of highs, like the second half of 2012, and lows, like the erratic losses and discussions. On the one hand, many young professionals managed to get their breakthrough and the team always knew it would be at the top of the table. On the other hand, they never succeeded beyond second and third place and had poor showings on the international level – mainly in qualifying rounds.

Their playing style often featured long balls to target man Pellè looking to win the second ball and take it to the wings. Many of the latter ended up with Schaken dribbling on the flanks and offsetting the mediocre shape of the team with his individual brilliance and improvisation. From time to time they had strong games that they dominated with their presence and counter pressing, which is another interesting mechanism they produced, e.g. Daryl Janmaat’s diagonal dribbling. The team pulsated with danger if they were able to focus on their solid, determined counterattacks, in which the quick wingers were supported by the movement of the eight. The defense was also caught out by their ambivalence. Despite a solid, base formation they executed things too chaotically. The man orientations and the somewhat unclear tasks played a role. The slightly unbalanced characteristics of the team’s forward movement led to vulnerability on the counter and long balls from the opposition that isolated Jordy Clasie or Tonny Vilhena a few times in physical duels. Ultimately, the coach was forgiven by Rotterdam as they earned a Champions League qualification spot thanks to good run of performances at the end of the season that were spurred on by the use of an interesting back five.

Overall, Koeman can be characterized as a coach who practices a solid, dominant formation. On attack there are a lot of forward movements and a tendency towards playing wide that manifests itself in crosses and focused passes or long balls to the target man. In between they play with small groups working space and an electricity to their attacks that can lead to some outstanding games.

Koeman is the upgrade

The Saints’ style under Pochettino was pleasant to look at and brought some attractive games to the pitch. The Argentine, however, had a mature Plan A but the rest of his notebook was blank. However, the Saints don’t have the individual quality to force their style of play. In addition, it may surprise some people that even Premier League teams learn how to deal with the opposition’s buildup and pressing structures. Koeman is now building a renewed, more flexible squad. Against several of the weaker teams they prefer to circulate the ball in the center of the pitch before moving it to the wings in the final third. The Saints want to dominate the game, showing who’s boss. They get caught up wanting to dribble too intricately, forcing them to send players like Davis or Schneiderlin to the wings to fix these situations and produce the breakthrough.

This did not succeed against ambitious teams like Tottenham Hotspur. Ex-trainer Pochettino knew what was in store. In the 1:0 home win, he positioned his defense deep. The connections from the smaller dribbles down the wing came to nothing and the space gained remained relatively scarce despite their initial dominance. Koeman has also learned from these experiences, however, and can adjust his team to a 4-2-4 and play more counter-focused. The Saints still have to find the right balance between different opponents but the right approach is there.

The biggest difference between Koeman and Pocchetino can be found on the touchline. Koeman plays more Dutch. This means he uses more traditional wingers rather than indenting halfbacks like his predecessor. Under Koeman, Mane, Tadic, or Long are sometimes very wide, almost on a level with Pellè. The end effects being breakthroughs after close ball control and a pace advantage in isolated challenges. This resulted in several of the goals in the thrashing of Sunderland. In this aspect they are purely English but at a high technical level.

Thick as a church wall

But what distinguishes their current success story from others? Five goals against in eleven games. They are the only team that has a one digit goals against record (you can almost hear Jose Mourinho scowling). They conceded two goals to Liverpool to start the season, one each against West Ham, QPR, and Tottenham. It is difficult to overwhelm this bulwark which is protected by clearly structured pressing phases.

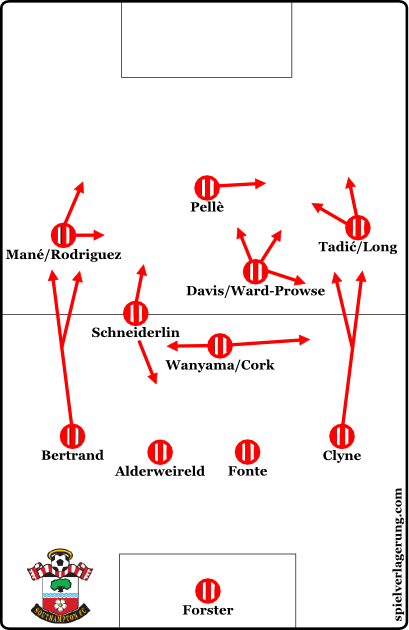

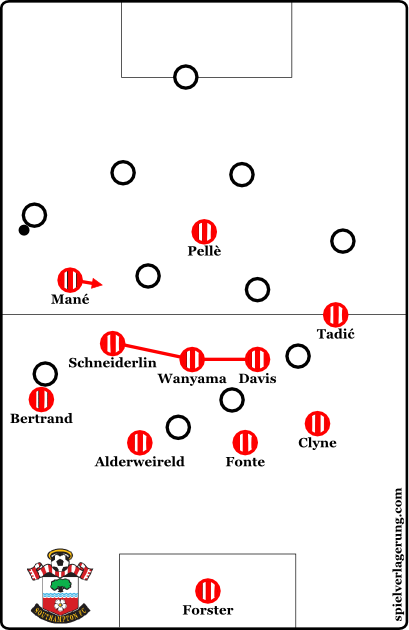

They have two different configurations. If they start against a 4-4-2 they play passively. For this shape, Tadic moves from the right to beside the center forward or Davis or Schneiderlin move forward to Pellè’s side of the pitch, which allows the wingers to fall back to the level of the sixes. Thus, the Saints are initially quite man-oriented against the opponent’s buildup, but allow space to be won, as it lets them move next into a 4-5-1. Generally, the most advanced eight slides into the central block. Afterwards, the team either shifts compactly in the direction of the ball, where the eight can move to the wing to generate pressure and prevent passes into the middle. In addition, there are always interesting shifts against the opposition full-backs. The respective Southampton winger will detach from the man orientation and indent a little bit. This deliberately leaves the wing open while the outermost eight pushes a bit towards the sideline. This gives access on the wing in the event of a vertical pass and also tries to force simple passes due to the deliberate gaps in the formation.

The central midfield functions like a pendulum, always orienting towards the ball and staying compact. While the wide, far players have the occasional problems finding space – one of the few weaknesses to date – Schneiderlin and Co. always maintain pressure. The space between the lines for the defensive line is heavily compressed. The opponent can only get in a cross by directly challenging the fullbacks and Alderweireld and Fonte can clear these balls very well. In challenges against weaker teams Southampton benefits from having the two central players, especially when the six space becomes less compact. The problem then becomes vertical compactness if one uses this method thoughtlessly. This is why Southampton uses a 4-5-1 with only three lines, where Pellé is on his own up front and doesn’t play a role in the deep pressing. If they pull together too radically in the box and allow the opponent quick combinations and layoff chances, the Saints can’t always act fast enough to resolve the compactness and build pressure again.

A more aggressive pressing variation is used in a 4-2-3-1 formation. The wingers move way up and mark the opposing full-backs. The ten slides between the opposing sixes while Soton’s six repeatedly attacks the next pass and upon forcing a back pass returns to the six space. Wanyama comes into play to great effect here as the Kenyan can cover the advances of Schneiderlin with his far-reaching, horizontal access area.

“What is defending? In Barcelona we won the CL and 4 Ligas with Koeman and Guardiola as defenders. Now if there are two examples of players who cannot defend its those two. But they did play in the heart of defense. So what is defending? Defending is about space. If I have to defend this whole garden, I’m the worst defender. If I have to defend this small area, I’m the best. It’s all about meters. That’s all.” (Johan Cruyff)

In search of Rhythm

Despite scoring 23 goals in eleven games, with eight scored in the destruction of Sunderland, there is still room for improvement in their attack design. Koeman employs great variability in his strategic design. Southampton, however, prefer to dominate games and determine the rhythm. Except for the first gameday, their possession ratio was always above 50 percent. Yet they still need to work on their transitions. As a target man, Pellé can hold the ball up with his back to goal for a brief time but can’t accelerate the play forward. In these situations, Tadic would actually be more appropriate, which would be difficult due to the layout of the team. There is a certain restraint in the rapid, chaotic advance of the whole team. The Saints seem reluctant to counter attack. Intruders in the six space – especially against the top teams – are not welcome. Overall, their attack rhythm is sometimes off and in tough games their dominant style seems to get out of hand as they vacillate between circulating the ball and dribbling in tight spaces and then suboptimal counter attacks. Koeman holds back too much in these games and doesn’t react to these lulls. In addition, his adjustments are rather simple. When leading a game, the 4-3-3 is often switched to a 4-4-1-1. While the Saints are behind, however, Koeman often brings on another attacker to make the formation a 4-2-4. The squad depth also prevents the Dutchman from experimenting. Southampton is, however, a step up from many teams in England in terms of their pressing. The Saints are the antithesis of the unwritten rules of the English top flight.

Their current position in the table shouldn’t be regarded as a definitive indicator of their potential threat on the international level. The schedule has been quite easy for them and they have only suffered defeats against Tottenham and Liverpool. In late November and early December, Southampton plays away to Arsenal and faces both Manchester teams at home. After the Christmas season, they will play Arsenal and Chelsea at St. Mary’s Stadium and also have to travel to Old Trafford. The final test for Koeman’s boys is yet to come.

Translated by @rafamufc.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen