Champions League final: Borussia Dortmund – Bayern Munich 1:2

Bayern Munich has won the UEFA Champions League 2013. It was a very suspenseful German final on a high level. The BVB’s somewhat riskier basic orientation led to more chances for both sides than in their last meetings and thus to an entertaining, dramatic game. After a dominant start of Westphalia, Bayern’s performance increased during the game. Two minutes before the end Arjen Robben’s winner crowned Munich’s strong second half.

Dortmund with a passive 4-4 2 attack-pressing

Who would start behind Lewandowski, replacing the injured Mario Götze? This was the crucial pre-game question. Jürgen Klopp opted for the established alternative, relied on the main double Six Gündogan / Bender and moved Reus to the centre. Kevin Grosskreutz featured in the start formation, but this was not the main difference. Borussia changed their approach especially in pressing.

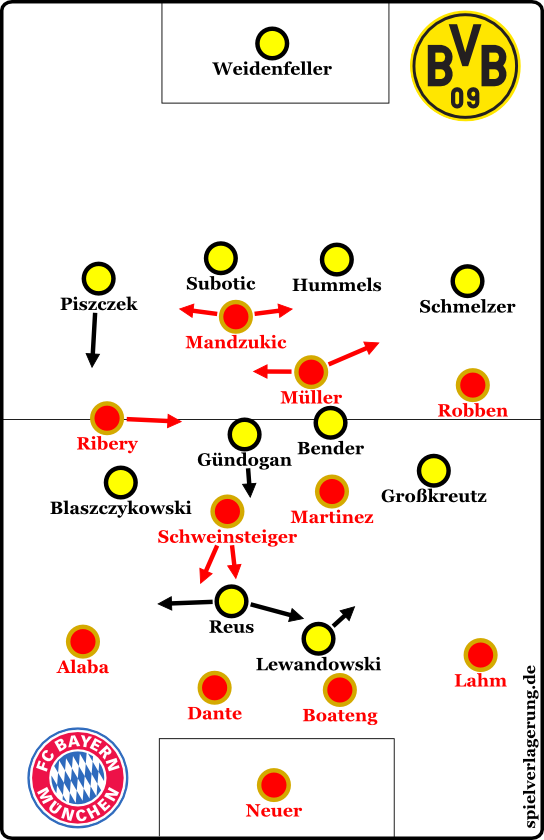

Against the ball, the BVB was positioned in direct attacking pressing – instead of a formation around the centreline with only situational movement further out. Lewandowski and Reus pushed out side by side in a 4-4-2, just in front of the opposing central defenders. The midfield four moved relatively far into Munich’s half.

Against the ball, the BVB was positioned in direct attacking pressing – instead of a formation around the centreline with only situational movement further out. Lewandowski and Reus pushed out side by side in a 4-4-2, just in front of the opposing central defenders. The midfield four moved relatively far into Munich’s half.

Reus and Lewandowski did not attack the central defenders aggressively, but in an unusually passive approach to attacking pressing. Despite the high ground position, the BVB focused on directing the opponent’s passing game by controlling the crucial key points and pass routes. The main ideas involve here concerned the early blocking of Boateng, and the pass route to Schweinsteiger was guarded with enormous attention as long as the playmaker was present in midfield.

Bavarian build-up play gets torn apart

Dortmund’s pressing approach turned some characteristics of Bayern’s build-up play against them. Firstly, they used Schweinsteiger’s movement (designed to to actively break free), on the other hand they used Thomas Müller’s forward orientation. The fluidity of the Bavarian wingers or the effects of their important fullbacks were thus nipped in the bud.

Alaba and Lahm were in fact pinned back by Dortmund’s high basic formation. They had to hold back to support the pressurized central defenders. Dortmund could prevent potential problems with shifts from side to side and afford a closer positioning in defensive play.

This was especially helpful against Ribéry. In the first half he had but little impact on the game. He needed Alaba to provide width against Piszczek’s tracking. The Bavarian movement in left half space was blocked.

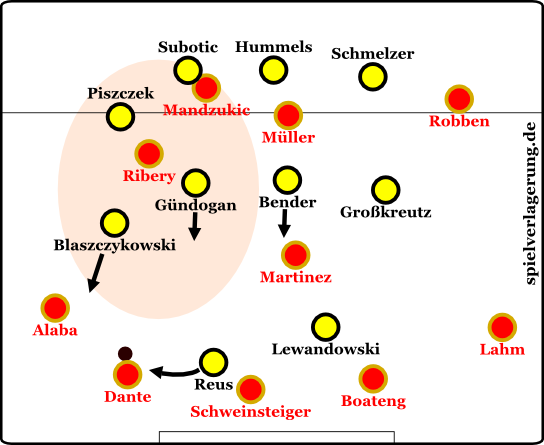

Dortmund’s pressing and Bayern’s tightened half-left midfield in the beginning. Bayern had only difficult access to decisive connection lines. Ribéry is closed in.

Schweinsteiger often tilts back between the central defenders or to the left from this area if the defensive has to be supported in build-up play. As Thomas Müller is oriented forward, Ribéry has to fill this gap to provide connection, resulting in tight space with Piszczek, Gündogan, and Blaszczykowski. Schweinsteiger was taken over by the Dortmund strikers positioned high.

Bayern could not play around this obstructed area in half-left midfield because of Dortmund’s focus on Boateng. The game was well kept away from Lahm and forced on the much less play-making Alaba. The left-back and Dante had no open men available and unusually often resorted to long balls that were not in sync with Bayern’s game plan. Since these passes were often played vertically along the left side, Dortmund dominated the second balls as well, due to Bayern’s “Schweinsteiger-hole”.

Dortmund counterattacks

Dortmund was also very strong in the centre, closely guarding the pass routes – one of their outstanding, collective skills. Thus, Martinez’ forward passing options were limited, even if he received the ball behind the strikers for once. Formed around him, Dortmund attacked the possible pass routes dynamically, and a “free” player put him under pressure.

Just because Bayern lacked connection between defensive and offensive, and as many of their players were pushed back, Dortmund was able to apply this very effectively and forced the opponent in midfield to repeatedly pass backward towards the defensive line. At best they could provoke a risky pass and intercept it in their movement.

In these scenes (albeit rarely allowed by Bayern’s intelligent players), the BVB then had plenty of space for counter attacks. Even after second balls hunted down on the right side they turned around quickly and attacked the holes in midfield. The Bayern’s torn-up side could not provide sufficient counter-pressing.

Ultimately, the counter-attacks yielded no results. Bayern’s advantages in speed usually prevented an effective Dortmund breakthrough. The back four tightened quickly and was supported by the holding midfielders. Borussia were only sporadically able to create an impact. The best scenes were nullified by the foul on Reus (see Dante’s yellow card) or by bad decisions of Blaszczykowski who is currently in very weak form on the ball.

In some scenes, Lewandowski and Reus went for a shot quickly. It often was the right decision and led to dangerous attempts on goal and corners. But on the other hand it was also an admission that Dortmund were not able to crack the Bavarian defensive, and Neuer was ultimately not to be duped by the risky shot attempts.

A game of second balls

Besides the counter-attacks, the BVB acted mostly with long balls to Lewandowski. They avoided Bayern’s pressing that might have led to dangerous ball conquests by an opponent so strong in counter-attacking. Only the central defenders retreated somewhat, occasionally assisted by Bender, to pull Müller and Mandzukic off the midfield line. Hummel moved a bit more to the outside to get room for his long balls.

Thus, the basic situation was similar in the end similar to the Bavarian one: The opening passes were mostly high long balls into half-left attacking space. However, the interpretation and defensive of this approach differed. In the initial phase, Dortmund could dominate in this aspect because they used this approach with obviously more direction.

In addition, Reus was oriented forward and picked his spots. Later, he should thereby provoke the penalty converted by Dortmund. These runs of Reus and the movements of Blaszczykowski and Grosskreutz around Lewandowski resulted in some confusion at Bayern. Martinez’ and Schweinsteiger’s man-oriented game was exploited, and the two sixes were pushed away again and again.

Access over security

Dortmund’s better presence around the target player resulted in more won second balls, but this caused only partially additional danger. Bayern’s defensive fought for loose balls in midfield without much access, but they were stable after lost balls.

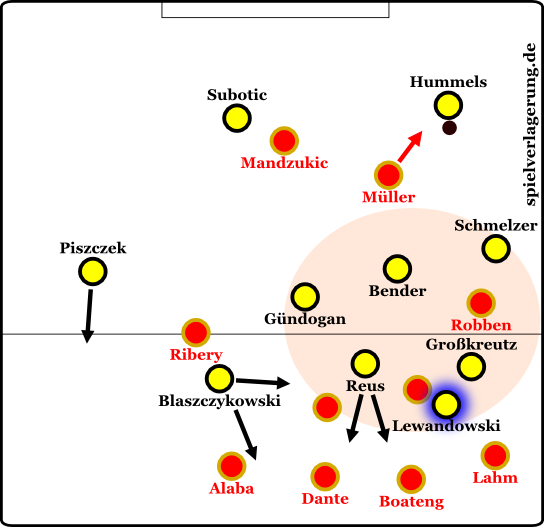

Dortmund’s defensive, however, was in a 4-on-4 when Bayern broke free. Balls bounced back rather into the space between the lines and not into midfield. As a result of the extended attacking pressing formation, Gündogan and Bender often had to cover long distances to ensure access. If this did not succeed, Bayern could immediately attack the defensive with many players.

In this respect, Dortmund’s optical dominance was built on quite shaky ground. As long as long balls were provoked and captured, the concept looked really good. But a single failure could lead to total collapse immediately. Müller demonstrated this most impressively: he got the better of Gündogan (30’) and enabled Robben to go into a 1-on-1 with Weidenfeller.

Details decide on this high level

This led to Bayern’s opening goal: Bayern broke free, and Mandzukic was able to convert. Dortmund made individually wrong decisions in this scene – at first, Subotic was overly in avoiding a duel with Mandzukic, then he attacked Ribéry together with Bender. Robben was thus free to receive Ribéry’s pass. In addition, Dortmund’s high position carried the risk that small errors could become extremely dangerous in such situations.

In addition, the 0:1 was an interesting footnote in the much-quoted “duel of goalkeepers”: Manuel Neuer cleared a difficult, high pass with elegant reception and a volley – still targeted so well that Mandzukic was able to control the ball. Weidenfeller on the other side came out to meet Robben and failed, while Neuer in a similar situation prevented Lewandowski’s breakthrough to the baseline. These may be little things, but those can obviously decide a Champions League final, and they should therefore be considered before you criticize national coach Jogi Löw. To be fair, however, it should be also mentioned that Weidenfeller otherwise made an outstanding game.

Bayern slowly gets into the game

The more important factor was Bayern’s growing presence; they clearly created more chances in the second half. This trend began after about 20 minutes, facilitated by changes in the passing rhythm and build-up play: Schweinsteiger tilted backwards less often and instead more to the left (for example just before Robben’s chance in the 30th minute), or even not at all. As a response, Dortmund positioned themselves somewhat deeper, and Bayern could no longer conduct attacks as effectively as before. Bayern were able to free themselves now and then with quick combinations along the wing.

After the initial stage, Robben also drifted less into the middle, but provided more width, as Lahm remained in a deep position. Dortmund became not quite as compact in dealing with second balls, and Schmelzer’s moving inside became risky.

Heynckes provides effective fine-tuning

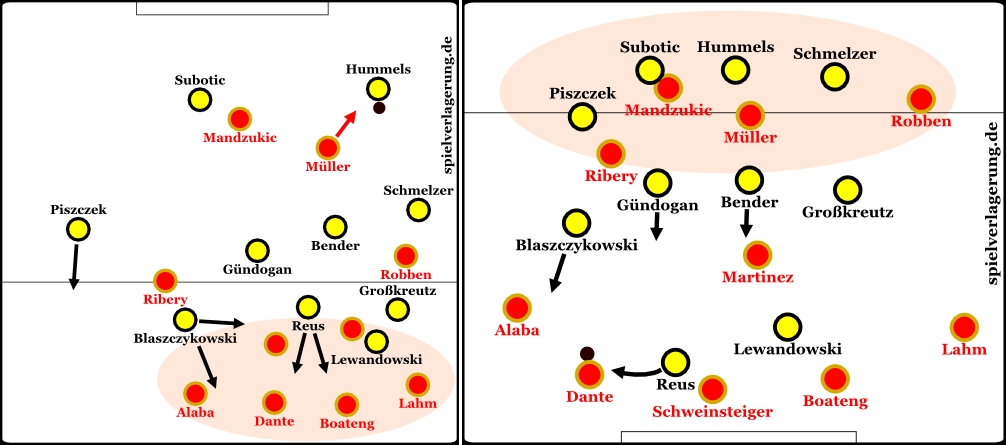

After half time break, Bayern’s pressing changed. The (until then) somewhat conductive and passive counter-pressing was changed into its classic aggressive variant, and the Bavarians became more present in dealing with second balls. In addition, their pressing against the central defenders got more dynamic.

Instead of attacking them directly, Bayern were positioned slightly deeper and with more caution. Situationslly, aggressive movement was employed. Dortmund was forced to pass back to Weidenfeller who distributed unplaced long balls. Bayern sat higher firmly, but at the back they naturally became unstable against the rare counterattacks.

In addition, Martinez and Schweinsteiger acted less man-oriented. The gaps in the defensive formation were reduced. Especially Martinez got better into the game and excelled increasingly in the second half. In addition to his strength in tackles, his pressing resistance was of crucial importance. Statistics say his passing accuracy was clearly the best on the field.

Munich came more often into the last third of the pitch and forced the BVB to withdraw, leading to a nerve-wrecking defensive of the box. More set pieces (in which both teams radiated danger) – before, Dortmund had been 5-0 up front regarding corners – meant even additional danger. Now, the full-backs could occasionally come forward, and for some periods, Dortmund was contained by counter-pressing. All in all Bayern rarely had to rely on open build-up play, rendering Dortmund’s pressing plan much less effective in the second half.

Overload by speed

Unassuming but also decisive was Bayern’s changed focus on long balls. Instead of trying to control the rebounds in the space between the lines they played these directly behind the defensive. Often, one of the offensive players would simply run through instead of waiting or going on the rebound. Both goals ultimately happened because Robben charged with full speed through the back four.

In addition, especially Mandzukic and Müller positioned themselves very proactively. Dortmund could thus not respond well to these deep runs. Often, a player was close to the receiver of a long ball, or easily accessible for this “second man”. Three players pooled up and could not be separated. Two very short ball contacts would suffice to reach the last man behind the defensive line.

Dortmund’s Sixes were therefore less and less supporting the defensive, which was increasingly overwhelmed by the faster opponents. Bayern seemed to focus on that by playing the long balls even a little higher and further. Thus, the defensive had to move further back, and the Sixes’ paths were even longer. During the last 30 minutes, the power in Dortmund’s defensive seemed to subside.

Dortmund plays along

In response to the goal in the 60th minute, Borussia took more of a risk in build-up play. The full-backs pushed forward earlier, and space in defensive midfield was better used. Gündogan was more present and increasingly fell back into the defensive to receive balls.

Before the 1:1 he pulled Mandzukic away in front of Hummels. The latter could push forward into midfield and bring the long ball from there to Schmelzer charging forward. Grosskreutz won the second ball and Reus appeared in front of Dante, who was caught unawares by Reus receiving the ball with his chest. At this point the often underrated Kevin Grosskreutz deserves praise for his performance: it was no accident that, behind Martinez, he had the second highest passing accuracy. The initiation of the penalty was the unnoticed crowning of his intelligent game.

After 1:1 Borussia kept to this approach and even increased the passing focus slightly. Now, they played along and wanted to get the win. This change in the tactical plan did not succeed, as Bayern could now use the dynamics of their pressing in midfield. They had been too passive after the 1:0. Although Gündogan and Hummels partially ventured into defensive midfield, but the offensive midfield was lacking in the counter-offensive – one might even say: Götze was missing and thus connection.

Dortmund’s instability yet increased because Munich could still build sporadic counter-attacking situations putting Borussia under quite some pressure. In addition, their presence on second balls faltered. It is surprising that Klopp did not bring strong passer Sahin into this phase of the game.

Until injury time the BVB only managed two long-range shots, while Bayern had several chances to score the winner from inside the box. Subotic’s sensational rescue act on the abandoned goal line might be seen as a symbol of Bayern’s superior final phase. After Robben’s goal there was too little time left, despite Klopp’s offensive substitutions featuring Sahin and Schieber for Bender and Blaszczykowski. Schieber missed in the last chance to score.

Conclusion

The moment in which the deciding goal was scored was somewhat tragic. It prevented the spectacle of Dortmund fighting back from happening, as well as a potentially terrific extension. Bayern had taken the game within an instant.

But for 88 minutes it was a wonderful game in which both teams came close to their limits. The current main German-German duel is probably bound to be dominated by pressing and transition play at the highest level. Both teams ran calculated risks and did not want to rely on a random scene. Instead of a defensive battle, we saw an eventful game with many shots on goal, great drama and high speed. Lawn Chess 2.0 – a German invention.

Tears and Triumphs

Bayern defeated their finals curse on the third attempt. A generation of German internationals can finally shed the unfair loser’s stamp, and a legendary coach named Jupp Heynckes gilded his farewell season (at least coaching the FCB) with the greatest triumph of them all and has reached the Olympus of Champions League coaches – after Ernst Happel, Ottmar Hitzfeld and Jose Mourinho, he is only the fourth coach who won the Champions League with two different clubs. The unparalleled season of these “record Bayern” is just one win away from a perfect finish, and they deserve the treble.

On the other side there is the Ballspielverein Borussia, who gave his supporters a unique Champions League season. The balanced final has shown that the club belongs to the world’s finest. Dortmund could not repeat their greatest triumph in club history, but this defeat may be more valuable for the club than the momentous victory 16 years ago. This time the final will not be the peak just before the crash, but quite the contrary. The Ruhrpott may look forward to the further development of a sensational team. Jürgen Klopp described this development as “the most interesting project in the world.” Such a project is not finished off by a goal in the penultimate game minute.

Spielverlagerung.de congratulates FC Bayern for winning the UEFA Champions League 2013!

Written by MR, translated by PF.

5 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Jacob May 29, 2013 um 10:33 am

I am trying to figure out why Bayern didn’t pull back all attacking player to involve in first 20min , especially Muller and Mandzukic were waiting on other side.

May be there were instructed to play more attacking(hoping Bayern’s back 4 will sending directly to final third)? or they r surprised by Dormund pressing and quick transition? or previous meeting “Kroos” was the key player who could help out in midfield in those situation?

I saw Bayern play more defensive against Barcelona.

I just do not know why Bayern didn’t impose at first since they were expecting Dortmund to counter?

SA Soccer Biz May 29, 2013 um 9:16 am

Fantastic analysis. It really was ‘lawn chess’, played with pace and a high technical quality. When players with talent also work hard, you have a winning combination. Sad to see 2 of the Dortmund team move across to Bayern – it will be a big step backwards for Klopp – very interested in his transfer activity now!

BVB3000 May 29, 2013 um 1:34 am

Bayern were incredible ruthless and pragmatic all season. They aren’t doing anything particularly revolutionary like classic Ajax or Milan, Barca (tiki-taka), Chelsea (physicality under Mourinho) or United (lightning quick counters, 2006-2009). They are blending different styles and adopt their game against different teams bringing a wonderful controlled aggression to their technical ability. Bayern are primarily a high-possession team, much like Barcelona, but the difference is that they are versatile and can adapt to their opponent. Possession is not the primary goal of their system, but high speed, consequently high risk counter attacks from a pressing midfield or a stable defense. When the opponent is weak, they of course are able to switch to a high control system like Barca.

They win, and they do so because they can adapt to any other side they face and simply refuse to be outworked. They ultimately have more options and can adapt and shift their gameplan facing different opponents. Last year and especially under van Gaal they were fare more rigid. The first 25 minutes against Dortmund they were almost playing a 3 man defense at the back with Boateng, Schweinsteiger and Dante to absorb the pressure.

Some points:

– They blend possession-based technical football with great pressing, attack and couter furiously quick, have great width and mix physical, aerial football (CBs, Martinez, Mandzukic) with a high work rate and very good teamwork

– The wings are worldclass power trains with Lahm/Muller (Robben) on the right and Alaba/Ribery left

– Bayern’s transition game is stunning when they loose possession. They are lightning quick to regain their defensive positions and their overall defensive shape

– Their pressing is miles better this season and even Robben and Ribery helping so much at the back

– Their current game is not based on one player as they have lots of different goal scorers

– Muller has evolved into the best attacking midfielder this season (if you count Messi as a forward). He simply has everything including incredible smart movement and a good defensive workrate. What a beast.

Keep up the good work Spielverlagerung!